Abstract

Introduction

Coronary flow velocity reserve (CFVR) is an important prognostic marker in patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD). Beta-blockers and ivabradine have been shown to improve CFVR in patients with stable CAD, but their effects were never compared. The aim of the current study was to compare the effects of bisoprolol and ivabradine on CFVR in patients with stable CAD.

Methods

Patients in sinus rhythm with stable CAD were enrolled in this prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Patients had to be in a stable condition for at least 15 days before enrollment, on their usual therapy. Patients who were receiving beta-blockers or ivabradine entered a 2-week washout period from these drugs before randomization. Transthoracic Doppler-derived CFVR was assessed in left anterior descending coronary artery, and was calculated as the ratio of hyperemic to baseline diastolic coronary flow velocity (CFV). Hyperemic CFV was obtained using dipyridamole administration using standard protocols. After CFVR assessment, patients were randomized to ivabradine or bisoprolol and entered an up-titration phase, and CFVR was assessed again 1 month after the end of the up-titration phase.

Results

Fifty-nine patients (38 male, 21 female; mean age 69 ± 9 years) were enrolled. Transthoracic Doppler-derived assessment of CFV and CFVR was successfully performed in all patients. Baseline characteristics were similar between the bisoprolol and ivabradine groups. No patient dropped out during the study. At baseline, rest and hyperemic peak CFV as well as CFVR was not significantly different in the ivabradine and bisoprolol groups. After the therapy, resting peak CFV significantly decreased in both the ivabradine and bisoprolol groups, but there was no significant difference between the groups (ivabradine group 20.7 ± 4.6 vs. 22.8 ± 5.2, P < 0.001; bisoprolol group 20.1 ± 4.1 vs. 22.1 ± 4.3, P < 0.001). However, hyperemic peak CFV significantly increased in both groups, but to a greater extent in patients treated with ivabradine (ivabradine: 70.7 ± 9.4 vs. 58.8 ± 9.2, P < 0.001; bisoprolol: 65 ± 8.3 vs. 58.7 ± 8.2, P < 0.001). Accordingly, CFVR significantly increased in both groups (ivabradine 3.52 ± 0.64 vs. 2.67 ± 0.55, P < 0.001; bisoprolol 3.35 ± 0.70 vs. 2.72 ± 0.55, P < 0.001), but it was significantly higher in ivabradine group, despite a similar decrease in heart rate (63 ± 7 vs. 61 ± 6; P not significant).

Conclusion

Ivabradine improves hyperemic peak CFV and CFVR to a greater extent than bisoprolol in patients with stable CAD, despite a similar decrease in heart rate. These data demonstrate that the benefits from ivabradine therapy go beyond the heart rate. This could be due to a different mechanism such as diastolic perfusion time, isovolumic ventricular relaxation, end-diastolic pressure, and collaterals.

Funding

Servier.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Elevated resting heart rate (HR) is considered a marker of cardiovascular risk in the general population and in patients with cardiovascular diseases. It is associated with a risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in healthy populations [1], and in patients with hypertension [2], coronary artery disease (CAD) [3], and chronic heart failure (HF) [4–6]. This negative prognostic value of a higher HR appears to be independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors [1, 3, 4, 6, 7].

Some HR-lowering agents have been shown to improve clinical outcomes, although whether HR reduction is the only mechanism of benefit is hard to demonstrate and could be reductive. Ivabradine reduces the HR without affecting blood pressure or left ventricular systolic function by inhibiting the I f current in the sinoatrial node. In patients with CAD and left ventricular systolic dysfunction, it is shown to reduce hospitalization for coronary revascularization and myocardial infarction (MI) [8]. Moreover, it was able to improve outcomes in patients who had a HR of 70 beats per minute (bpm) or more.

Coronary flow velocity reserve (CFVR) is defined as the ratio of hyperemic to basal peak velocity flow and reflects the functional capacity of adaptation of coronary microcirculation during cardiac work. It depends on the combined effects of epicardial coronary stenosis and microvascular dysfunction. Transthoracic Doppler echocardiography (TTDE) allows non-invasive assessment of CFVR in the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) [9–12]. TTDE-derived CFVR measurement is not only useful to diagnose obstructive coronary artery narrowing [13, 14], but is also useful to assess microvascular function [15, 16].

Previous reports have shown that reduced CFVR is an important prognostic marker in patients with non-obstructive CAD [17–20]. Beta-blockers and ivabradine have been shown to improve CFVR in patients with stable CAD [21–23], but their effects were never compared. The aim of the current study was to compare the effect of bisoprolol and ivabradine on CFV and CFVR in patients with stable CAD, and to better understand the effect of these drugs on coronary flow.

Methods

Trial Design

This prospective, randomized, double-blind trial enrolled patients in sinus rhythm with stable CAD. Stable CAD was defined as previous MI at least 6 months before randomization, previous surgical or percutaneous revascularization (at least 6 months) or angiographic evidence of at least 50% narrowing of ≥1 major coronary vessel.

Exclusion criteria were: unlikely cooperation in the study; pregnancy or breastfeeding; recent (<6 months) MI or coronary revascularization; history of stroke or cerebral transient ischemic attack (<3 months); scheduled surgical or percutaneous revascularization; at least one criterion among implanted pacemaker or cardioverter defibrillator, scheduled surgery for valvular disease, sick sinus syndrome, sinoatrial block, congenital long QT, complete atrioventricular block and severe or uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure >180 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure >110 mmHg).

After providing written informed consent, patients entered a 2-week washout phase from beta-blocker or ivabradine therapy to confirm eligibility and clinical stability. At the end of the run-in phase, patients had to be more than 18 years old, in sinus rhythm with resting HR ≥60 bpm, preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (≥50%), and in a stable condition for at least 15 days.

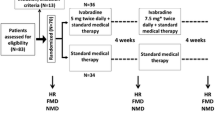

If eligibility and clinical stability were confirmed during the run-in phase, patients were randomly assigned, in a double-blind protocol, to receive either ivabradine at a starting dose of 2.5 mg twice daily or bisoprolol at a starting dose of 1.25 mg twice daily. Both drugs were weekly up-titrated, according to the HR, to the highest tolerated dose (maximum dosage: 7.5 mg twice daily for ivabradine and 5 mg twice daily for bisoprolol). After up-titration phase, patients received ivabradine or bisoprolol for another month. Patients were to receive stable background therapy according to contemporary guidelines. The study was approved by internal Ethics Committee. All procedures followed were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013.

Coronary Flow Reserve

Transthoracic Doppler-derived assessment of CFV and CFVR was performed at baseline and after 1 month of treatment, using a Vivid™ 7 ultrasound system (GE Healthcare). Coronary flow was assessed in the distal tract of the LAD using a modified apical two-chamber view. Peak diastolic velocity was measured at baseline and after dipyridamole infusion (0.84 mg/kg over 6 min), as envisaged by a well-established protocol [24, 25]. Baseline and hyperemic peak diastolic velocities were obtained from three consecutive cardiac cycles, and CFVR was calculated as the ratio of hyperemic to baseline peak diastolic velocity.

All measurements were performed offline, using EchoPAC™ Clinical Workstation Software (GE Healthcare), by two experienced echocardiographers, blinded to all clinical data. The intra- and inter-observer variability of measurements was 4% and 6%, respectively, and was assessed in 10 consecutive patients.

Statistical Analysis

The baseline characteristics are shown as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and as numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Unpaired t test was used to analyze differences in continuous variables among groups; paired t test was used to analyze differences within groups. Analysis of categorical data was performed using the Chi-squared test. All tests of hypotheses were two-sided and a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS Statistics Software (V22.0, IBM, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

In total, 59 patients (38 male, 21 female) were enrolled in the study. Baseline characteristics were similar in the two groups (Table 1). The study population had a mean age of 69 ± 9 years (35.6% female), and a resting HR of 72.2 ± 9.3 bpm. Overall, 22% of the patients had a previous MI, 36% had previous coronary revascularization, while 34% had exertional angina.

Twenty-four patients (41%) had angiographic evidence of at least 50% narrowing of ≥1 major coronary vessel: 11 patients had coronary stenosis of LAD (4 patients with narrowing between 70% and 80% were equally randomized to ivabradine or bisoprolol to avoid bias), 9 patients of left circumflex artery and 7 patients of right coronary artery.

Patients were already receiving appropriate therapy for CAD, according to contemporary guidelines, when enrolled in the trial.

The average dosage of the drugs was 6.3 ± 1.1 mg twice daily in the ivabradine group and 5.8 ± 0.8 mg twice daily in the bisoprolol group. One month after the end of the up-titration phase, mean HR significantly decreased, as expected, in both groups, without significant differences between the groups (from 73 ± 10 to 63 ± 7 bpm in ivabradine group, P < 0.001; from 71 ± 9 to 61 ± 6 bpm in bisoprolol group, P < 0.001; Table 2). Dipyridamole infusion was well tolerated and CFVR was successfully performed in all patients.

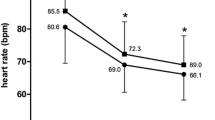

Doppler parameters of CFV and CFVR are given in Table 2. At baseline, rest and hyperemic peak CFV as well as CFVR was not significantly different in the ivabradine and bisoprolol groups. After therapy, resting peak CFV significantly decreased in both the ivabradine and bisoprolol groups, but without significant difference among them. However, hyperemic peak CFV significantly increased in both groups, but to a greater extent in the ivabradine group. Accordingly, CFVR significantly increased in both groups, but to a greater extent in the ivabradine group (Fig. 1). All of these results were obtained despite a similar lowering of HR (63 ± 7 vs. 61 ± 6 bpm, P not significant; Table 2; Fig. 2). None of the patents dropped out during the study.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that ivabradine increases hyperemic CFV and CFVR to a greater extent than bisoprolol, despite a similar HR reduction. The mechanism underlying differences between ivabradine and beta-blockers on CFV and CFVR is hypothetical, but extremely intriguing.

Resting HR is an important and independent risk factor, with important prognostic implications, as a predictor for cardiovascular mortality and morbidity, independently of other risk factors [1–7]. Thus, several pharmacological treatments have been proposed to reduce HR and improve the outcome of patients with CAD and HF. However, it can be reductive to say that every effect of these drugs is only due to HR reduction.

Ivabradine is a selective inhibitor of the I f channel, first described by Thollon et al. [26] in 1997. Inhibiting the f (“funny”) channel, which controls the electrical pacemaker activity in the sinoatrial node, ivabradine induces a decrease in HR in patients with sinus rhythm, both at rest and with exercise. Bradycardia prolongs diastole and improves ventricular filling, which leads to lesser myocardial oxygen consumption and allows increased coronary flow and myocardial perfusion [27]. Unlike other rate-reducing agents like beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers, ivabradine does not decrease systemic blood pressure [28], does not suppress myocardial contractility [28, 29], and does not cause atrioventricular conduction abnormalities [30]. Specifically, it does not alter QT interval or repolarization duration as well as conductivity or refractoriness of ventricles, His-Purkinje system, atrioventricular node and atrium [30]. Four isoforms of the I f channel gene were identified in the animal hearts [31, 32], and HCN2, whose levels are higher in the sinus node [33], is considered to be the dominant isoform.

Ivabradine reduces the entry of sodium into the myocytes, with consequent reduction of cytosolic calcium, and improves the reuptake of calcium by the sarcoplasmic reticulum, leading to an improvement of ventricular relaxation [34, 35].

Ivabradine and Beta-Blockers

Ivabradine and beta-blockers, as their HR-lowering effects, are often still considered “similar” drugs. In large clinical trials, ivabradine has been investigated as an alternative to beta-blockers, when these agents cannot be tolerated or are contraindicated, or in addition, when HR is not adequately controlled with the highest tolerated dose of beta-blockers.

But we should wonder if their effect is really so similar. Recently, multiple mechanisms have been proposed to explain differences between ivabradine and beta-blockers. Several experimental studies reported a beneficial effect of ivabradine that was at least in part HR independent and supported the so-called “pleiotropic actions” of ivabradine [36–39]. Thus, which is the key to better understand the differences between ivabradine and bisoprolol on coronary flow?

Coronary blood flow occurs mostly during diastole, when there is a reduced compression of the coronary vessels by the surrounding muscular cardiac fibers as compared to the systolic period. It is clear that diastolic perfusion time mainly affects subendocardial blood flow. Furthermore, coronary flow can be affected by the pressure gradient between mean diastolic pressure in the aortic root and diastolic ventricular pressure. This pressure gradient and the duration of the diastole are integrated into the diastolic pressure–time integral [40], and anything that modifies the diastolic pressure–time integral will modify coronary blood flow: it is here that we can find the key of the differences between ivabradine and bisoprolol on coronary blood flow.

The effects of ivabradine and atenolol, a beta-blocker, on diastolic time have been compared in two experiments [41, 42]. Ivabradine increased diastolic time both at rest and during treadmill exercise to a greater degree than atenolol, though HR was similar with both drugs. As a result, ivabradine causes a greater increase in coronary blood flow at exercise for the same reduction in HR compared with beta-blockers (as demonstrated in experiments), because of the greater prolongation of diastolic filling time of coronary arteries.

Beta-blockers, with their negative lusitropic action, in contrast to ivabradine, impair isovolumic ventricular relaxation, offsetting part of the benefits of prolonged diastolic duration, and this may be another reason for the difference between ivabradine and bisoprolol on CFV and CFVR [43].

Moreover, with ivabradine there is not an increase or unmasking of alpha-adrenergic coronary vasoconstriction, compared with beta-blockers, in the epicardial coronary arteries and even more in the coronary microcirculation [44].

Finally, the development of collateral circulation represents a natural mechanism to compensate for the limitation of coronary flow with progression of coronary stenosis and is advantageous protection tissue from ischemia. Patel et al. [45] demonstrated that there is an association between bradycardia and growth of collateral vessels in patients with obstructive CAD. It was suggested that HR-reducing agents might be useful for promoting the development of coronary collaterals in patients with atherosclerotic disease. Recently, Gloekler et al. [46] assessed the effect of ivabradine on the human coronary collateral circulation. The results of this first-time clinical, placebo-controlled randomized study demonstrated that ivabradine improves coronary collateral function in patients with stable CAD. Theoretically, improved coronary collateral function could affect Doppler-derived coronary flow reserve, although specific trials should confirm this hypothesis.

Limitations

Not all patients underwent coronary angiography just before enrollment. A small study population was included and, accordingly, no statistical data on clinical endpoints were obtained. Moreover, no data on any subsequent revascularization were collected as follow-up was closed after coronary flow assessment.

Conclusions

This study shows for the first time in humans that ivabradine significantly improves hyperemic peak CFV and CFVR to a greater extent than a beta-blocker, in patients with stable CAD, demonstrating that ivabradine not only has an anti-anginal but also an anti-ischemic effect. Similar HR reduction obtained with both drugs implies that the effect of ivabradine treatment goes beyond the HR. Differences between ivabradine and bisoprolol could be due to a different effect on diastolic perfusion time and isovolumic ventricular relaxation, as well as unmasking of alpha-adrenergic coronary vasoconstriction by beta-blockers. Theoretically, an overall improvement of diastolic function and a positive effect on coronary collateral function could further explain differences between ivabradine and beta-blockers on CFV and CFVR. The next questions that the medical community has to answer are as follows: Does ivabradine have an advantage over beta-blockers? Does ivabradine have other therapeutic effects beyond HR reduction that make it a preferable agent?

References

Jouven X, Empana JP, Schwartz PJ, Desnos M, Courbon D, Ducimetiere P. Heart-rate profile during exercise as a predictor of sudden death. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1951–8.

Palatini P, Benetos A, Julius S. Impact of increased heart rate on clinical outcomes in hypertension: implications for antihypertensive drug therapy. Drugs. 2006;66:133–44.

Diaz A, Bourassa MG, Guertin MC, Tardif JC. Long-term prognostic value of resting heart rate in patients with suspected or proven coronary flow velocity. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:967–74.

Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG, Tendera M, Robertson M. Ferrari R; BEAUTIFUL investigators. Heart rate as a prognostic risk factor in patients with coronary artery disease and left-ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:817–21.

Swedberg K, Komajda M, Bohm M, et al. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomized placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2010;376:875–85.

Bohm M, Swedberg K, Komajda M, et al. Heart rate as a risk factor in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): the association between heart rate and outcomes in a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:886–94.

Fox K, Borer JS, Camm AJ, et al. Resting heart rate in cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:823–30.

Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG, Tendera M, Robertson M, Ferrari R. BEAUTIFUL investigators. Ivabradine for patients with stable coronary artery disease and left-ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:807–16.

Caiati C, Montaldo C, Zedda N, Bina A, Iliceto S. New non invasive method for coronary flow reserve assessment: contrast-enhanced transthoracic second harmonic echo Doppler. Circulation. 1999;99:771–8.

Daimon M, Watanabe H, Yamagishi H, et al. Physiologic assessment of coronary artery stenosis by coronary flow reserve measurements with transthoracic Doppler echocardiography: comparison with exercise thallium-201 single piston emission computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1310–5.

Takeuchi M, Miyazaki C, Yoshitani H, Otani S, Sakamoto K, Yoshikawa J. Assessment of coronary flow velocity with transthoracic Doppler echocardiography during dobutamine stress echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:117–23.

Hozumi T, Yoshida K, Akasaka T, et al. Noninvasive assessment of coronary flow velocity and coronary flow velocity reserve in the left anterior descending coronary artery by Doppler echocardiography: comparison with invasive technique. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1251–9.

Rigo F, Richieri M, Pasanisi E, et al. Usefulness of coronary flow reserve over regional wall motion when added to dual-imaging dipyridamole echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:269–73.

Nohtomi Y, Takeuchi M, Nagasawa K, Arimura K, Miyata K, Kuwata K. Simultaneous assessment of wall motion and coronary flow velocity in the left anterior descending coronary artery during dipyridamole stress echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16:457–63.

Lee DH, Youn HJ, Choi YS, et al. Coronary flow reserve is a comprehensive indicator of cardiovascular risk factors in subjects with chest pain and normal coronary angiogram. Circ J. 2010;74:1405–14.

Cortigiani L, Rigo F, Gherardi S, Bovenzi F, Picano E, Sicari R. Implication of the continuous prognostic spectrum of Doppler echocardiographic derived coronary flow reserve on left anterior descending artery. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:158–62.

Cortigiani L, Rigo F, Gherardi S, et al. Additional prognostic value of coronary flow reserve in diabetic and nondiabetic patients with negative dipyridamole stress echocardiography by wall motion criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1354–61.

Sicari R, Rigo F, Cortigiani L, Gherardi S, Galderisi M, Picano E. Additive prognostic value of coronary flow reserve in patients with chest pain syndrome and normal or near-normal coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:626–31.

Rigo F, Sicari R, Gherardi S, Djordjevic-Dikic A, Cortigiani L, Picano E. Prognostic value of coronary flow reserve in medically treated patients with left anterior descending coronary disease with stenosis 51% to 75% in diameter. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:1527–31.

Rigo F, Sicari R, Gherardi S, Djordjevic-Dikic A, Cortigiani L, Picano E. The additive prognostic value of wall motion abnormalities and coronary flow reserve during dipyridamole stress echo. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:79–88.

Billinger M, Seiler C, Fleisch M, Eberli FR, Meier B, Hess OM. Do beta-adrenergic blocking agents increase coronary flow reserve? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1866–71.

Togni M, Vigorito F, Windecker S, et al. Does the beta-blocker nebivolol increase coronary flow reserve? Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2007;21:99–108.

Skalidis EI, Hamilos MI, Chlouverakis G, Zacharis EA, Vardas E. Ivabradine improves coronary flow reserve in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2011;1:160–5.

Armstrong WF, Pellikka PA, Ryan T, Crouse L, Zoghbi WA. Stress echocardiography: recommendations for performance and interpretation of stress echocardiography. Stress Echocardiography Task Force of the Nomenclature and Standards Committee of the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1998;11:97–104.

Sicari R, Nihoyannopoulos P, Evangelista A, et al. European Association of Echocardiography. Stress echocardiography expert consensus statement: European Association of Echocardiography (EAE) (a registered branch of the ESC). Eur J Echocardiogr. 2008;9:415–37.

Thollon C, Bidouard JP, Cambarrat C, et al. Stereospecific in vitro and in vivo effects of the new sinus node inhibitor (+)-S 16257. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;339:43–51.

Di Francesco D, Camm JA. Heart rate lowering by specific and selective I(f) current inhibition with ivabradine: a new therapeutic perspective in cardiovascular disease. Drugs. 2004;64(16):1757–65.

Joannides R, Moore N, Iacob M, et al. Comparative effects of ivabradine, a selective heart rate-lowering agent, and propranolol on systemic and cardiac haemodynamics at rest and during exercise. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61(2):127–37.

Manz M, Reuter M, Lauck G, Omran H, Jung W. A single intravenous dose of ivabradine, a novel I(f) inhibitor, lowers heart rate but does not depress left ventricular function in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Cardiology. 2003;100(3):149–55.

Camm AJ, Lau CP. Electrophysiological effects of a single intravenous administration of ivabradine (S 16257) in adult patients with normal baseline electrophysiology. Drugs. 2003;4(2):83–9.

Accili EA, Proenza C, Baruscotti M, Di Francesco D. From funny current to HCN channels: 20 years of excitation. News Physiol Sci. 2002;17:32–7.

Ludwig A, Zong X, Jeglitsch M, Hofmann F, Biel M. A family of hyperpolarization-activated mammalian cation channels. Nature. 1998;393:587–91.

Shi W, Wymore R, Yu H, et al. Distribution and prevalence of hyperpolarization-activated cation channel (HCN) mRNA expression in cardiac tissues. Circ Res. 1999;85:e1–6.

Ceconi C, Cargnoni A, Francolini G, Parinello G, Ferrari R. Heart rate reduction with ivabradine improves energy metabolism and mechanical function of isolated ischaemic rabbit heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;84:72–82.

Gewirtz H. ‘Funny’ current: if heart rate slowing is not the best answer, what might be? Cardiovasc Res. 2009;84:9–10.

Heusch G, Skyschally A, Gres P, van Caster P, Schilawa D, Schulz R. Improvement of regional myocardial blood flow and function and reduction of infarct size with ivabradine: protection beyond heart rate reduction. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2265–75.

Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG, Tendera M, Robertson M, Ferrari R, BEAUTIFUL Investigators. Relationship between ivabradine treatment and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with stable coronary artery disease and left ventricular systolic dysfunction with limiting angina: a subgroup analysis of the randomized, controlled BEAUTIFUL trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2337–45.

Heusch G. A BEAUTIFUL lesson—ivabradine protects from ischaemia, but not from heart failure: through heart rate reduction or more? Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2300–1.

Heusch G. Pleiotropic action(s) of the bradycardic agent ivabradine: cardiovascular protection beyond heart rate reduction. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:970–1.

Buckberg GD, Fixler DE, Archie JP Jr, Hoffman JIE. Experimental subendocardial ischemia in dogs with normal coronary arteries. Circ Res. 1972;30:67–81.

Colin P, Ghaleh B, Monnet X, et al. Contributions of heart rate and contractility to myocardial oxygen balance during exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H676–82.

Colin P, Ghaleh B, Monnet X, Hittinger L, Berdeaux A. Effect of graded heart rate reduction with Ivabradine on myocardial oxygen consumption and diastolic time in exercising dogs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:236–40.

Colin P, Ghaleh B, Hittinger L, et al. Differential effects of heart rate reduction and beta-blockade on left ventricular relaxation during exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H672–9.

Monnet X, Ghaleh B, Colin P, Parent De Curzon O, Giudicelli J-F, Berdeaux A. Effects of heart rate reduction with ivabradine on exercise induced myocardial ischemia and stunning. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:1133–9.

Patel SR, Breall JA, Diver DJ, Gersh BJ, Levy AP. Bradycardia is associated with development of coronary collateral vessels in humans. Coron Artery Dis. 2000;11(6):467–72.

Gloekler S, Traupe T, Stoller M, et al. The effect of heart rate reduction by Ivabradine on collateral function in patients with chronic stable coronary artery disease. Heart. 2014;100(2):160–6.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship, article processing charges, and the open access charge for this study were funded by Servier. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

Ercole Tagliamonte, Teresa Cirillo, Fausto Rigo, Costantino Astarita, Antonino Coppola, Carlo Romano and Nicola Capuano have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tagliamonte, E., Cirillo, T., Rigo, F. et al. Ivabradine and Bisoprolol on Doppler-derived Coronary Flow Velocity Reserve in Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease: Beyond the Heart Rate. Adv Ther 32, 757–767 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-015-0237-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-015-0237-x