Abstract

Lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of disease entities with well-defined clinical, morphological, immunophenotypic, and cytogenetic characteristics. Moreover, regional and racial differences have been reported in their incidence and subtype compositions. Here, we reviewed the epidemiology of lymphomas and summarized the recent achievements in specific subtypes prevalent in Korean population, focusing on clinical studies conducted by the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL) of the Korean Society of Hematology Lymphoma Working Party (KSH-LWP).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lymphomas are the most common hematologic malignancies and a heterogenous group of neoplasms with diverse clinical presentations and histological and biological features. They originate from neoplastic clones of B, T, or natural killer (NK) cells and are classified based on clinical, morphological, immunophenotypic, and cytogenetic characteristics [1]. The classification of lymphoid neoplasms was derived from the Revised European–American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms (REAL) published by the International Lymphoma Study Group in 1994 [2] and the World Health Organization classification (WHO) of lymphoid neoplasms first published in 2001 and revised in 2008 and 2016 [3, 4].

As diagnoses and classification systems for lymphoid neoplasms have been established, there have been efforts to investigate and report the epidemiology of lymphomas. Likewise, the Korea Central Cancer Registry (KCCR) and the Korean Society of Hematology (KSH) jointly investigated the domestic prevalence and incidence rates of hematologic malignancies since 1999 and analyzed survival rates of patients [5, 6]. Different incidence rates and trends have been reported for specific subtypes of lymphomas among regions, and some discriminative features were reported in the Asian population in the United States or Europe [7]. For example, decreased incidence rate in the Asian population for overall lymphoid malignancies was observed, which was prominent for follicular lymphoma (FL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). However, Asians showed an increased incidence rate of the marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) and extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma (ENKTL), nasal type [8,9,10].

In this article, we comprehensively reviewed the incidence, distribution, and survival rates of lymphoid neoplasms in Korean population based on the KCCR data. Furthermore, we summarized recent advances in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches focusing on clinical trials conducted by the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL) of the Korean Society of Hematology Lymphoma Working Party (KSH-LWP).

Korean lymphoma epidemiology

Cancer registration in Korea

In 1980, the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare initiated the KCCR, a nationwide hospital-based cancer registry for collecting data from 47 hospitals in Korea, and became the entire population-based cancer registry program in 1999. KCCR subsequently published annual reports on cancer statistics in Korea, and the latest 2014 version was issued in October 2016. Initially, cancer diagnosis was classified according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology 3rd edition (ICD-O-3), which was converted to the International Classification of Diseases 10th edition (ICD-10). Incidence data from 1999 to 2012 were obtained from the Korea National Cancer Incidence Database (KNCI DB). The completeness of incidence data in 2012 was 97.7%, as determined by the Ajiki method [11].

Incidence of lymphoid neoplasms and subtypes between 1999 and 2012

Lee et al. reported the subtype-specific statistical analysis of lymphoid malignancies in the Korean population in 2017, based on the KCCR annual report data between 1999 and 2012 [12]. This article contained the most recent data regarding the details of each subtype in lymphoid neoplasms, and the authors comprehensively analyzed the incidences and changes of survival rates over 20 years. We summarized Korean lymphoma epidemiology mainly based on the results in this article and the annual report of cancer statistics in Korea. Between 1999 and 2012, a total of 65,948 cases of lymphoid neoplasms occurred, which comprised 3.0% of all cancers reported. Based on subtypes, mature B-cell neoplasms (42,647 cases, 64.7%) were the most common, followed by precursor cell neoplasms (7409 cases, 11.2%), unknown types (6618 cases, 10.0%), and mature T- and NK-cell neoplasms (6612 cases, 10.0%) (Fig. 1a). Eleven cases of composite Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma were not included (Fig. 1). Among the mature B-cell neoplasms excluding plasma cell disorders (11,169 cases, 26.2% of mature B-cell neoplasms), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL; 19,659 cases, 62.5%) was the most common subtype, followed by MZL (6716 cases, 21.3%) (Fig. 1b). The incidences of follicular lymphoma (FL; 1498 cases, 4.8%) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic leukemia (CLL/SLL; 1495 cases, 4.7%) were relatively lower than those in the Western population [13, 14]. Among the mature T- and NK-cell neoplasms, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS; 2157 cases, 32.6%), was the most common, followed by ENKTL (1846 cases, 27.9%), angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL; 831 cases, 12.6%), anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL; 786 cases, 11.9%), and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL; 744 cases, 11.3%) (Fig. 1c). Similar to other Asian countries, the incidence of ENKTL was higher than that in the Western countries [15, 16].

Incident cases of the a entire lymphoid neoplasms, b mature B-cell lymphoma, and c mature T- and NK-cell lymphoma between 1999 and 2012. b DLBCL diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, MZL marginal zone lymphoma, FL follicular lymphoma, CLL/SLL chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic leukemia, BL Burkitt lymphoma, MCL mantle cell lymphoma, LDP lymphoproliferative disorder. c PTCL-NOS peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified, ENKTL extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, AITL angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, ALCL anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, CTCL cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

Annual changes on the incidence based on subtypes and age group

Figure 2 presents the annual incidences of all lymphoid neoplasms and each subtype between 1999 and 2012. In 1999, 3233 cases of lymphoid neoplasms were reported to the registry. In 2012, a total of 6638 cases of lymphoid neoplasms were reported, including 4844 cases of mature B-cell neoplasms and 634 cases of T- and NK-cell neoplasms. During this period, the crude incident rate (CR) and age-standardized incidence rate (ASR) of all lymphoid neoplasms increased from 6.85 to 13.18 and 6.89 to 9.93, respectively. Furthermore, the annual percentage change (APC) of ASR was 3.2%, with statistical significance of p < 0.05). Between 1999 and 2012, the ASRs of mature B-cell neoplasms and mature T- and NK-cell neoplasms increased from 3.41 to 6.60 (APC 5.6%) and from 0.47 to 0.95 (APC 6.6%), respectively. Moreover, ASR increased from 0.24 to 0.46 in HL (APC 5.0%) and from 1.33 to 1.50 in precursor cell neoplasms (APC 1.4%). However, ASR of unknown types decreased from 1.44 to 0.41 (APC − 9.3%).

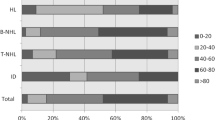

Figure 3 presents the incidences based on age group in 2012. A high incidence of lymphoid neoplasms was observed in the group aged 50–79 years. Mature B-cell neoplasms were the most prevalent subtype in all groups aged ≥ 20 years. However, precursor cell neoplasms were the most common subtype in patients aged < 20. The peak incidence of HL was observed at between 20 and 29 years of age, which was different from the bimodal distribution observed in the Western population. The unknown type of lymphoid neoplasm was relatively rare in the younger patient group.

Survival changes based on time in major subtypes

The KCCR has been collecting survival data of patients with cancer since their first diagnosis in 1993. Lee et al. analyzed the survival rates of patients with lymphoid neoplasms based on the data available in the KNCI DB between 1993 and 2012 [12]. Patients with lymphoid neoplasms were divided by 5-year intervals (1993–1997, 1998–2002, 2003–2007, and 2008–2012) and major subtypes such as HL, DLBCL, PTCL, and ENKTL. The 5-year relative survival rate (5-RSR) of all lymphoid neoplasms between 1993 and 1997 was 45.3%, which gradually increased to 61.7% in 2008–2012. The 5-RSR improved in most subtypes of lymphoid neoplasms. The HL showed the most favorable 5-RSR, from 71.1% in 1993–1997 to 83.0% in 2008–2012. The 5-RSR of mature B-cell neoplasms improved from 42.8 to 63.8%, with the greatest improvement observed between 1998–2002 and 2003–2007 (47.9 and 58.7%). This increment (10.8%) is consistent with the results of survival in DLBCL, comparing the pre- and post-rituximab eras in the United States [17]. For similar reason, survival rates for FL also increased in this period. However, the survival rates for T- and NK-cell neoplasms, except CTCL, did not improve during this period (5-RSR, 44.2% to 44.2% between 1993–1997 and 2008–2012, respectively). The 5-RSR of ENKTL improved from 45.8% in 2003–2007 to 49.9% in 2008–2012, because concomitant or sequential chemotherapy and radiation therapy became the standard treatment in early stages of ENKTL [18, 19], and l-asparaginase-based regimens were introduced for advanced diseases [20, 21]. However, most subtypes of T-cell lymphoma were under unsatisfactory situations with lack of successful trials on new drug combinations. The survival rates for acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma also significantly improved with 56.3% of 5-RSR in 2008–2012.

Recent advances in Korean lymphoma focusing on CISL trials

CISL

CISL of KSH-LWP is a multicenter collaborative study group for patients with lymphoma [22]. The first meeting was held in February 2006, with 10 institutions and 12 members and, currently, the CISL comprises 69 centers. By the end of 2017, the CISL has published the results of 36 retrospective studies to investigate the clinical and pathological features of Korean-specific lymphoma subtypes and evaluate the outcomes of new therapeutic modalities. Moreover, they also have performed more than 35 prospective clinical trials and reported the results of 20 prospective trials for DLBCL, MZL, ENKTL, and other subtypes [23]. Figure 4 presents the prospective chronological flow of prospective CISL trials.

Chronological flow of prospective trials in Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL). DLBCL diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, MZL marginal zone lymphoma, MCL mantle cell lymphoma, ENKTL extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, HL Hogkin lymphoma, ASCT autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

HL

CISL evaluated the clinical and histopathological characteristics, therapeutic outcomes, and prognostic factors of Korean patients with HL [24]. A total of 539 patients with HL from 16 centers were retrospectively analyzed between 1985 and 2010. This study revealed lower incidence of HL in Korea than in Western countries and similar distribution of morphologic subtypes and treatment outcomes. The median age of all patients was 40 years, and the peak incidence was found in the group aged 16–30 years. Among the 539 patients, 506 (93.9%) had classical HL and 267 (48.7%) had advanced stages (Ann Arbor stage III or IV) at the time of initial diagnosis.

B-cell neoplasms

DLBCL

To retrospectively analyze DLBCL, CISL has focused on the diseases in the extranodal primary sites, such as the breast, ovary, intestine, adrenal gland, and sinonasal tract. A retrospective analysis of primary breast DLBCL reported different treatment outcomes, prognoses, and progression patterns between patients with only one extranodal disease in the breast and multiple sites of extranodal disease [25]. Moreover, a matched-pair analysis comparing the outcomes of primary breast and nodal DLBCL was also performed. Overall survival (OS) was similar between the two groups in rituximab era; however, extranodal progression in the breast or central nervous system (CNS) was more common in the primary breast DLBCL than in the nodal DLBCL [26]. Outside the CISL group, a single-center analysis emphasized the number of extranodal sites involved as the most significant prognostic factor for event-free survival (EFS) and OS in R-CHOP-treated patients with disseminated DLBCL [27]. The CISL also conducted a retrospective cohort study to analyze the effect of surgery on the outcomes and quality of life (QoL) in the intestinal DLBCL [28]. This study showed that surgical resection followed by chemotherapy is an effective treatment strategy with acceptable QoL deterioration for localized intestinal DLBCL. The CISL also reported the prognostic factors in primary DLBCL of adrenal gland, and suggested that achieving complete response (CR) after R-CHOP is predictive survival [29]. Recently, primary sinusoidal tract DLBCL treated with R-CHOP was retrospectively investigated. The results suggested that introduction of rituximab improved the OS and reduced CNS relapse in patients with sinusoidal tract DLBCL [30]. Moreover, the CISL analyzed 1585 DLBCL patients with bone marrow (BM) aspirates at diagnosis. Histologic BM involvement and chromosomal abnormalities were found in 259 (16.3%) and 192 (12.1%) patients, respectively. We subsequently reported that multiple cytogenetic abnormalities in the BM were associated with poor prognosis. [31].

For the prospective study in DLBCL, the CISL started a phase I/II study of bortezomib plus CHOP every 2 weeks (Vel-CHOP-14) in patients with advanced stage of DLBCL in 2006 (CISL 0603). In phase II, the overall response rate (ORR) was 95% [CR 80%; partial response (PR) 15%]. However, 9 out of 40 patients (22.5%) showed grade 3/4 sensory neuropathy, and 22 (55.0%) required at least 1 dose reduction. We concluded that Vel-CHOP-14 was highly effective for the treatment of untreated DLBCL; however, dose or schedule modification was required to reduce neurotoxicity [32]. Since 2010, the CISL has tried weekly rituximab (R) consolidation following four cycles of R-CHOP in elderly (≥ 70 years) patients (CISL 1006). We showed an acceptable response with high tolerability of R consolidation, with 78.4% of ORR, 63.9% of 2-year PFS, and 68.7% of 2-year OS [33]. Most recently, the CISL conducted a prospective cohort study with risk-adapted CNS evaluation in DLBCL (CISL 1006, 1107). We analyzed 595 patients with DLBCL who received R-CHOP and revealed that highly elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, more than 3 times the upper limit of the normal range) is an independent prognostic factor for CNS relapse [34].

Another mainstream of clinical trials in CISL targeting DLBCL was radioimmunotherapy (RIT). First, radioiodinated rituximab (131I-rituximab) was attempted in relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) (CISL 0602). RIT with 131I-rituximab seemed to be effective in low-grade lymphoma; however, only 1 PR was observed in 11 patients with refractory DLBCL (9% ORR) [35]. Based on this study, a follow-up phase II trial for repeated RIT with 131I-rituximab was conducted (CISL 1013). 131I-rituximab was administered with 4-week interval. In 7 DLBCL patients, 42.9% of ORR (1 in CR and 2 in PR) and 5.0 months of median duration of response were observed [36]. The multicenter, pilot trial of yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) consolidation after R-CHOP was performed in a limited stage, bulky DLBCL (CISL 0607). Twenty-one patients with CR or PR after R-CHOP were enrolled, with 3-year PFS and OS of 75.0 and 85.0%, respectively [37].

Furthermore, the CISL has tried alternative regimens for relapsed or refractory DLBCL. ESHAOx [etoposide (E), methylprednisolone (S), high-dose cytarabine (HA), and oxaliplatin (Ox)] for refractory/relapsed aggressive NHL (CISL 0802) and GIDOX [gemcitabine (G), ifosfamide (I), dexamethasone (D), and oxaliplatin (OX)] for B-cell NHL (CISL 0702) were prospectively investigated and resulted in 63 and 52% of ORR, respectively [38, 39]. Both regimens could be considerable options for salvage treatment in relapse or refractory DLBCL.

MZL

As previously mentioned, MZL is relatively common in Koreans and was a primary target for research in the early days of the CISL. We have reported a very wide range of retrospective studies associated with MZL and the sites involved. Nodal, intestinal, and non-gastric MZL were analyzed [40,41,42], and rare primary sites such as the lungs, thyroid, and Waldeyer’s ring were also investigated [43,44,45]. More recently, we reported that stage I/II MZL was well controlled with a local treatment such as radiation therapy or surgery and showed a good clinical course without additional chemotherapy [46]. However, rituximab has played a significant role in stage IV MZL [47].

In 2006, the CISL conducted phase II trial of rituximab plus CVP (R-CVP) for untreated stage III or IV MZL (CISL 0605). Of the 40 patients, the ORR and median duration of response were 88% and 28.3 months, respectively. The R-CVP can be an effective first-line regimen for advanced stage MZL [48]. Furthermore, we also tried phase II trial for gemcitabine monotherapy in advanced stage MZL; however, the clinical activity was minimal (CISL 0606) [49]. Recently, oxaliplatin and prednisone (Ox-P) combination was investigated in relapsed or refractory MZL (CISL 0905). Salvage Ox-P chemotherapy showed moderate clinical activity (64.7% of ORR) and tolerable toxicity [50].

Other subtypes of B-cell neoplasms

A total of 131 patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) were retrospectively analyzed. The median age was 63 years, and 105 (80.2%) patients had advanced stage of disease. The BM and intestines were involved in 41.2 and 35.1% of patients, respectively. We found simplified MCL international prognostic index (sMIPI) was an important prognostic factor in Korean patients with MCL [51]. In 2012, a phase II study for vorinostat combined with fludarabine, mitoxantrone, and dexamethasone (V-FND) in patients with relapsed or refractory MCL was conducted and resulted in 77.8% ORR and 9.3 months median PFS (CISL 1201). We concluded that V-FND is an effective regimen for relapsed or refractory MCL; however, significant hematologic adverse events including neutropenia (grade 3/4 in 50%) and thrombocytopenia (grade 3/4 in 35%) were not negligible [52].

For Burkitt lymphoma (BL), treatment outcomes of R-hyper-CVAD regimen were retrospectively evaluated in 43 patients, and the 2-year EFS and OS were 70.9 and 81.4%, respectively. However, significant toxicity and unsatisfactory tolerance in Korean patients were observed [53].

In 2016, the CISL retrospectively analyzed 343 patients with FL in Korea. We showed different tendencies compared with those in the Western population, especially with respect to high histologic grade, relatively low stage of disease, and low BCL-2 expression [54].

T-cell neoplasms

ENKTL

For ENKTL, the CISL has introduced the unique performance and outcomes. In 2010, we analyzed 208 patients with ENKTL to evaluate clinical features and outcomes of CNS disease. The Ann Arbor stage, regional lymph node involvement, and NK/T-cell lymphoma prognostic index (NKPI) were used in predicting CNS disease. We concluded that patients with NKPI group I or II do not need a routine CNS evaluation; however, CNS prophylaxis should be considered in patients with NKPI groups II–IV [55]. Next, a multinational retrospective study of ENKTL from the skin or soft tissue was conducted. We analyzed 48 patients with skin/soft tissue primary ENKTL and identified that Korean prognostic index (KPI) score is a useful predictor of prognosis. Moreover, the addition of radiation therapy might have a role in treating localized disease. In metastatic disease, anthracycline-containing regimens were ineffective [56]. Most recently, a prognostic index for NK-cell lymphoma (PINK) after non-anthracycline-based treatment was established by a multinational, retrospective analysis of 527 patients from 38 hospitals in 11 countries. These data showed that age > 60 years, advanced stage, distant lymph node involvement, and non-nasal type were significantly associated with prognosis, and these factors were merged into “PINK.” Furthermore, an Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) DNA titer was an independent prognostic factor for the OS. These results were validated in an independent cohort. Thus, PINK and PINK combined with EBV DNA (PINK-E) were established as new prognostic models for risk-adapted treatment approaches [19].

In treating localized ENTKL, three major prospective trials were performed by CISL. Based on the benefits of frontline radiotherapy in the early stages of ENKTL, the first phase II trial of concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) followed by three cycles of etoposide, ifosfamide, cisplatin, and dexamethasone (VIPD) in stage IE to IIE disease was conducted in 2006 (CISL 0601). Among the 30 patients who completed CCRT, all of them achieved a positive response, with 22 patients in the CR. Twenty-six patients completed the scheduled three cycles of VIPD after CCRT and resulted in 83.3% ORR and 80.0% CR. We concluded that newly diagnosed and early stages of ENKTL are best treated with frontline CCRT [18]. The next trial was CCRT followed by two cycles of VIDL, replacing cisplatin with l-asparaginase due to toxicity (CISL 0803). Among the 30 patients with stages IE and IIE nasal ENKTL, VIDL chemotherapy showed an 87% final CR (26/30), and the estimated 5-year PFS and OS were 73% and 60%, respectively [57]. In 2016, CISL published the results of phase II trial of CCRT with l-asparaginase and methotrexate, ifosfamide, dexamethasone, and l-asparaginase (MIDLE) chemotherapy for stage I/II ENTKL (CISL 1008). We designed a new treatment protocol by adding tri-weekly intravenous or intramuscular l-asparaginase doses during the radiotherapy, and two cycles of MIDLE were repeated every 4 weeks. This protocol showed 82.1% final CR, and the 3-year PFS and OS were 74.1 and 81.5%, respectively. However, concurrent administration of l-asparaginase during CCRT seemed not to be beneficial [58].

PTCL and other subtypes of T-cell neoplasms

For PTCL, the CISL reported a retrospective study on lymphopenia as an independent prognostic indicator to predict the OS and PFS in PTCL-NOS patients treated with anthracycline-containing chemotherapy [59]. Another retrospective study on non-bacterial infections in Asian patients treated with alemtuzumab was conducted and analyzed 182 patients receiving alemtuzumab as frontline, salvage, or part of the conditioning regimen for allogeneic transplantation. Reactivation of cytomegalovirus (n = 66), varicella zoster virus (n = 25), fungal infections (n = 31), and Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (n = 4) was observed. Thus, we recommended antimicrobial prophylaxis in Asian patients receiving alemtuzumab [60].

The CISL has focused on the innovative prospective trials on T-cell neoplasms. We designed a prospective phase II study of alemtuzumab and DHAP (A-DHAP) for relapsed PTCL or ENKTL and briefly reported 50.0% ORR in 16 patients (CISL 0604) [61]. Moreover, the CISL conducted a phase I study of bortezomib plus CHOP (Vel-CHOP) regimen in patients with advanced, aggressive T- or NK/T-cell lymphoma in 2007 (CISL 0701). Thirteen patients with stage III/IV aggressive T-cell lymphoma were treated with Vel-CHOP as a first-line therapy, and 61.5% CR was reported. We concluded that Vel-CHOP could be a safe regimen and recommended a bortezomib dose of 1.6 mg/m2 for subsequent phase II trial [62]. Based on this study, we consequently performed phase II trial of Vel-CHOP for a first-line treatment in advanced T-cell lymphoma (CISL 0705). Forty-six patients with various subtypes of T-cell lymphoma were enrolled, and 30 (65.2%) patients achieved CR. Consequently, 3-year PFS and OS were 35 and 47%, respectively [63]. Another phase I study of everolimus and CHOP was performed in newly diagnosed PTCL patients, and everolimus plus CHOP regimen could be feasible and effective (CISL 1108) [64]. Sequentially, a phase II study was conducted on 30 patients with PTCL. The ORR was 90% with CR in 17 patients and PR in 10 patients. Interestingly, the efficacy was associated with loss of PTEN [65]. We investigated the salvage chemotherapy using gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin (GDP) for patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL (CISL 1003). Fourteen patients with PTCL-NOS and 4 patients with AITL were enrolled, and 12 had a CR and 6 had a PR. The median PFS was 9.3 months. GDP is a highly effective treatment regimen for relapsed or refractory PTCLs and could be an optional salvage treatment [66].

Ongoing clinical trials and future perspectives

Since 2006, Korean researchers for lymphoid neoplasms and the CISL have focused on lymphoma subtypes relatively common in Korea, such as DLBCL, MZL, ENKTL, and PTCL. Moreover, clinical studies have been conducted in collaboration with specialists, such as pathologists, radiologists, radiotherapists, and physicians of diagnostic laboratories and nuclear medicine. As of November 2017, there were 13 ongoing studies in the CISL, with 6 phase II or III trials in B-cell neoplasms, 3 phase II trials in T-cell neoplasms, and 4 prospective cohort or registry studies. Furthermore, several prospective cohort studies and clinical trials on DLBCL, MCL, and primary CNS lymphoma have also been planned. In the future, we plan to continue working with researchers from various countries in Asia to improve the survival of lymphoma patients.

References

Williams WJ, Kaushansky K, Lichtman MA, Prchal JT, Levi MM, Press OW, et al. Williams hematology. New York. NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, Banks PM, Chan JK, Cleary ML, et al. A revised European–American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 1994;84:1361–92.

Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011;117:5019–32.

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375–90.

Park HJ, Park EH, Jung KW, Kong HJ, Won YJ, Lee JY, et al. Statistics of hematologic malignancies in Korea: incidence, prevalence and survival rates from 1999 to 2008. Korean J Hematol. 2012;47:28–38.

Huh J. Epidemiologic overview of malignant lymphoma. Korean J Hematol. 2012;47:92–104.

Phillips AA, Smith DA. Health disparities and the global landscape of lymphoma care today. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:526–34.

Muller AM, Ihorst G, Mertelsmann R, Engelhardt M. Epidemiology of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL): trends, geographic distribution, and etiology. Ann Hematol. 2005;84:1–12.

Chihara D, Ito H, Matsuda T, Shibata A, Katsumi A, Nakamura S, et al. Differences in incidence and trends of haematological malignancies in Japan and the United States. Br J Haematol. 2014;164:536–45.

Bassig BA, Au WY, Mang O, Ngan R, Morton LM, Ip DK, et al. Subtype-specific incidence rates of lymphoid malignancies in Hong Kong compared to the United States, 2001–2010. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;42:15–23.

Ajiki W, Tsukuma H, Oshima A. Index for evaluating completeness of registration in population-based cancer registries and estimation of registration rate at the Osaka Cancer Registry between 1966 and 1992 using this index. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 1998;45:1011–7.

Lee H, Park HJ, Park EH, Ju HY, Oh CM, Kong HJ, et al. Nationwide statistical analysis of lymphoid malignancies in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50:222–38.

Marcos-Gragera R, Allemani C, Tereanu C, De Angelis R, Capocaccia R, Maynadie M, et al. Survival of European patients diagnosed with lymphoid neoplasms in 2000–2002: results of the HAEMACARE project. Haematologica. 2011;96:720–8.

Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:271–89.

Aozasa K, Takakuwa T, Hongyo T, Yang WI. Nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma: epidemiology and pathogenesis. Int J Hematol. 2008;87:110–7.

Haverkos BM, Pan Z, Gru AA, Freud AG, Rabinovitch R, Xu-Welliver M, et al. Extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKTL-NT): an update on epidemiology, clinical presentation, and natural history in North American and European cases. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2016;11:514–27.

Shah BK, Bista A, Shafii B. Survival in advanced diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in pre- and post-rituximab eras in the United States. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:5117–20.

Kim SJ, Kim K, Kim BS, Kim CY, Suh C, Huh J, et al. Phase II trial of concurrent radiation and weekly cisplatin followed by VIPD chemotherapy in newly diagnosed, stage IE to IIE, nasal, extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma: Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6027–32.

Kim SJ, Yoon DH, Jaccard A, Chng WJ, Lim ST, Hong H, et al. A prognostic index for natural killer cell lymphoma after non-anthracycline-based treatment: a multicentre, retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:389–400.

Jaccard A, Gachard N, Marin B, Rogez S, Audrain M, Suarez F, et al. Efficacy of l-asparaginase with methotrexate and dexamethasone (AspaMetDex regimen) in patients with refractory or relapsing extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, a phase 2 study. Blood. 2011;117:1834–9.

Kwong YL, Kim WS, Lim ST, Kim SJ, Tang T, Tse E, et al. SMILE for natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: analysis of safety and efficacy from the Asia Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2012;120:2973–80.

Suh C, Kim WS, Kim JS, Park BB. Review of the clinical research conducted by the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma of the Korean Society of Hematology Lymphoma Working Party. Blood Res. 2013;48:171–7.

Suh C, Park BB, Kim WS. The Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL): recent achievements and future perspective. Blood Res. 2017;52:3–6.

Won YW, Kwon JH, Lee SI, Oh SY, Kim WS, Kim SJ, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in Korea: Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL). Ann Hematol. 2012;91:223–33.

Yhim HY, Kang HJ, Choi YH, Kim SJ, Kim WS, Chae YS, et al. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors in patients with breast diffuse large B cell lymphoma; Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL) study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:321.

Yhim HY, Kim JS, Kang HJ, Kim SJ, Kim WS, Choi CW, et al. Matched-pair analysis comparing the outcomes of primary breast and nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in patients treated with rituximab plus chemotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:235–43.

Yoo C, Kim S, Sohn BS, Kim JE, Yoon DH, Huh J, et al. Modified number of extranodal involved sites as a prognosticator in R-CHOP-treated patients with disseminated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Korean J Intern Med. 2010;25:301–8.

Kim SJ, Kang HJ, Kim JS, Oh SY, Choi CW, Lee SI, et al. Comparison of treatment strategies for patients with intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: surgical resection followed by chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. Blood. 2011;117:1958–65.

Kim YR, Kim JS, Min YH, Hyunyoon D, Shin HJ, Mun YC, et al. Prognostic factors in primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of adrenal gland treated with rituximab-CHOP chemotherapy from the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL). J Hematol Oncol. 2012;5:49.

Lee GW, Go SI, Kim SH, Hong J, Kim YR, Oh S, et al. Clinical outcome and prognosis of patients with primary sinonasal tract diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab-cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone chemotherapy: a study by the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:1020–6.

Kim S, Kim H, Kang H, Kim J, Eom H, Kim T, et al. Clinical significance of cytogenetic aberrations in bone marrow of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: prognostic significance and relevance to histologic involvement. J Hematol Oncol. 2013;6:76.

Kim JE, Yoon DH, Jang G, Lee DH, Kim S, Park CS, et al. A phase I/II study of bortezomib plus CHOP every 2 weeks (CHOP-14) in patients with advanced-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Korean J Hematol. 2012;47:53–9.

Jung SH, Lee JJ, Kim WS, Lee WS, Do YR, Oh SY, et al. Weekly rituximab consolidation following four cycles of R-CHOP induction chemotherapy in very elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma study (CISL). Eur J Haematol. 2015;94:504–10.

Kim SJ, Hong JS, Chang MH, Kim JA, Kwak JY, Kim JS, et al. Highly elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase is associated with central nervous system relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results of a multicenter prospective cohort study. Oncotarget. 2016;7:72033–43.

Kang HJ, Lee SS, Kim KM, Choi TH, Cheon GJ, Kim WS, et al. Radioimmunotherapy with (131)I-rituximab for patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2011;7:136–45.

Kang HJ, Lee SS, Byun BH, Kim KM, Lim I, Choi CW, et al. Repeated radioimmunotherapy with 131I-rituximab for patients with low-grade and aggressive relapsed or refractory B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:945–53.

Yang DH, Kim WS, Kim SJ, Kim JS, Kwak JY, Chung JS, et al. Pilot trial of yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan consolidation following rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone chemotherapy in patients with limited-stage, bulky diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:807–11.

Sym SJ, Lee DH, Kang HJ, Nam SH, Kim HY, Kim SJ, et al. A multicenter phase II trial of etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine, and oxaliplatin for patients with primary refractory/relapsed aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;64:27–33.

Park BB, Kim WS, Eom HS, Kim JS, Lee YY, Oh SJ, et al. Salvage therapy with gemcitabine, ifosfamide, dexamethasone, and oxaliplatin (GIDOX) for B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a consortium for improving survival of lymphoma (CISL) trial. Invest New Drugs. 2011;29:154–60.

Oh SY, Ryoo BY, Kim WS, Kim K, Lee J, Kim HJ, et al. Nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: analysis of 36 cases. Clinical presentation and treatment outcomes of nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2006;85:781–6.

Oh SY, Kwon HC, Kim WS, Hwang IG, Park YH, Kim K, et al. Intestinal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type: clinical manifestation and outcome of a rare disease. Eur J Haematol. 2007;79:287–91.

Oh SY, Ryoo BY, Kim WS, Park YH, Kim K, Kim HJ, et al. Nongastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: analysis of 247 cases. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:446–52.

Oh SY, Kim WS, Kim JS, Kim SJ, Kwon HC, Lee DH, et al. Pulmonary marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type—what is a prognostic factor and which is the optimal treatment, operation, or chemotherapy?: Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL) study. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:563–8.

Oh SY, Kim WS, Kim JS, Kim SJ, Lee S, Lee DH, et al. Primary thyroid marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type: clinical manifestation and outcome of a rare disease—Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma study. Acta Haematol. 2012;127:100–4.

Oh SY, Kim WS, Kim JS, Kim SJ, Lee S, Lee DH, et al. Waldeyer’s ring marginal zone B cell lymphoma: are the clinical and prognostic features nodal or extranodal? A study by the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL). Int J Hematol. 2012;96:631–7.

Koh MS, Kim WS, Kim SJ, Oh SY, Yoon DH, Lee SI, et al. Is there role of additional chemotherapy after definitive local treatment for stage I/II marginal zone lymphoma?: Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL) study. Int J Hematol. 2015;102:420–5.

Oh SY, Kim WS, Kim JS, Kim SJ, Lee S, Lee DH, et al. Stage IV marginal zone B-cell lymphoma-prognostic factors and the role of rituximab: Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL) study. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:2443–7.

Kang HJ, Kim WS, Kim SJ, Lee JJ, Yang DH, Kim JS, et al. Phase II trial of rituximab plus CVP combination chemotherapy for advanced stage marginal zone lymphoma as a first-line therapy: Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL) study. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:543–51.

Oh SY, Kim WS, Lee DH, Kim SJ, Kim SH, Ryoo BY, et al. Phase II study of gemcitabine for treatment of patients with advanced stage marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL) trial. Invest New Drugs. 2010;28:171–7.

Oh SY, Kim WS, Kim JS, Chae YS, Lee GW, Eom HS, et al. A phase II study of oxaliplatin and prednisone for patients with relapsed or refractory marginal zone lymphoma: Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma trial. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57:1406–12.

Kang BW, Sohn SK, Moon JH, Chae YS, Kim JG, Lee SJ, et al. Clinical features and treatment outcomes in patients with mantle cell lymphoma in Korea: study by the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma. Blood Res. 2014;49:15–21.

Shin DY, Kim SJ, Yoon DH, Park Y, Kong JH, Kim JA, et al. Results of a phase II study of vorinostat in combination with intravenous fludarabine, mitoxantrone, and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma: an interim analysis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77:865–73.

Hong J, Kim SJ, Ahn JS, Song MK, Kim YR, Lee HS, et al. Treatment outcomes of rituximab plus hyper-CVAD in Korean patients with sporadic Burkitt or Burkitt-like lymphoma: results of a multicenter analysis. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;47:173–81.

Cho SH, Suh C, Do YR, Lee JJ, Yun HJ, Oh SY, et al. Clinical features and survival of patients with follicular lymphoma in Korea. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016;16:197–202.

Kim SJ, Oh SY, Hong JY, Chang MH, Lee DH, Huh J, et al. When do we need central nervous system prophylaxis in patients with extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type? Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1058–63.

Ahn HK, Suh C, Chuang SS, Suzumiya J, Ko YH, Kim SJ, et al. Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma from skin or soft tissue: suggestion of treatment from multinational retrospective analysis. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2703–7.

Kim SJ, Yang DH, Kim JS, Kwak JY, Eom HS, Hong DS, et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy followed by l-asparaginase-containing chemotherapy, VIDL, for localized nasal extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma: CISL08-01 phase II study. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:1895–901.

Yoon DH, Kim SJ, Jeong SH, Shin DY, Bae SH, Hong J, et al. Phase II trial of concurrent chemoradiotherapy with l-asparaginase and MIDLE chemotherapy for newly diagnosed stage I/II extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (CISL-1008). Oncotarget. 2016;7:85584–91.

Kim YR, Kim JS, Kim SJ, Jung HA, Kim SJ, Kim WS, et al. Lymphopenia is an important prognostic factor in peripheral T-cell lymphoma (NOS) treated with anthracycline-containing chemotherapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2011;4:34.

Kim SJ, Moon JH, Kim H, Kim JS, Hwang YY, Intragumtornchai T, et al. Non-bacterial infections in Asian patients treated with alemtuzumab: a retrospective study of the Asian Lymphoma Study Group. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:1515–24.

Kim SJ, Kim K, Kim BS, Suh C, Huh J, Ko YH, et al. Alemtuzumab and DHAP (A-DHAP) is effective for relapsed peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified: interim results of a phase II prospective study. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:390–2.

Lee J, Suh C, Kang HJ, Ryoo BY, Huh J, Ko YH, et al. Phase I study of proteasome inhibitor bortezomib plus CHOP in patients with advanced, aggressive T-cell or NK/T-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:2079–83.

Kim SJ, Yoon DH, Kang HJ, Kim JS, Park SK, Kim HJ, et al. Bortezomib in combination with CHOP as first-line treatment for patients with stage III/IV peripheral T-cell lymphomas: a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:3223–31.

Hyun SY, Cheong JW, Kim SJ, Min YH, Yang DH, Ahn JS, et al. High-dose etoposide plus granulocyte colony-stimulating factor as an effective chemomobilization regimen for autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma previously treated with CHOP-based chemotherapy: a study from the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:73–9.

Kim SJ, Shin DY, Kim JS, Yoon DH, Lee WS, Lee H, et al. A phase II study of everolimus (RAD001), an mTOR inhibitor plus CHOP for newly diagnosed peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:712–8.

Park BB, Kim WS, Suh C, Shin DY, Kim JA, Kim HG, et al. Salvage chemotherapy of gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin (GDP) for patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphomas: a consortium for improving survival of lymphoma (CISL) trial. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:1845–51.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoo, K.H., Lee, H., Suh, C. et al. Lymphoma epidemiology in Korea and the real clinical field including the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL) trial. Int J Hematol 107, 395–404 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-018-2403-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-018-2403-9