Abstract

In this study we examine the collective labor supply choices of dual-earner parents and take into account child care expenditures. For this purpose we use data of the Flemish Families and Care Survey (FFCS, 2004–2005). The main findings are, firstly, that the supply of paid labor is hardly affected by changes in the prices of child care services. Secondly, child care price effects on the individual labor supplies are much smaller than the wage effects. Thirdly, we find that additional earnings due to an increase in household non-labor income minus the child care expenditures are mainly transferred to the wife.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The utility function of parent s under caring preferences can be represented as: U s = f s(u m(X m, Q, l m), u f(X f, Q, l f)), s = m, f (see Becker 1991).

The proof is given in Chiappori (1992).

In addition it holds that the sharing rule is identifiable up to an additive constant κ(z) when we would assume that preferences and the sharing rule are simultaneously influenced by certain preference factors (z).

Labor supply would depend on the spouse’s wage when we would assume caring preferences and the demand function of parent m would then write: \(h^{m}=\Lambda^{m}(w_{m},w_{f},\rho(w_{m},w_{f},\tilde{y},d,z),z)\).

Theoretically, this restrictions means that it cannot be the case that \(\frac{\partial h^{m}/\partial\tilde{y}}{\partial h^{f}/\partial\tilde{y}}\) equals \(\frac{\partial h^{m}/\partial d}{\partial h^{f}/\partial d}\).

See Chiappori et al. (2002). Furthermore, we have that \(\frac{\partial}{\partial w_{f}}\left(\frac{BC}{D-C}\right)=\frac{\partial}{\partial w_{m}}\left(\frac{AD}{D-C}\right)\) which is similar to \(\frac{\partial}{\partial w_{f}}\left(BC\right)=\frac{\partial}{\partial w_{m}}\left(AD\right)\). When we substitute A, B, C, D and determine these derivatives we have that \(\frac{\alpha_{6}\beta_{5}}{\alpha_{4}\beta_{4}w_{m}w_{f}} = \frac{\beta_{6}\alpha_{5}}{\alpha_{4}\beta_{4}w_{m}w_{f}}\) which simplifies to α 6 β 5 = β 6 α 5.

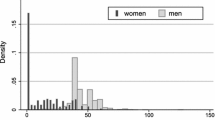

Net hourly wages refer to wages net of taxes and social security contributions as reported by the respondents (“take away pay”). Wages are expressed in hourly amounts through a division of the stated monthly labor income by the reported “usual weekly working hours” (multiplied by 4.33). To avoid division bias we used the latter, rather than the observed weekly working hours in the reference week that we use as an indicator of working hours (see text).

Bivariate Anova tests gives F-values that do not reach any of the conventional thresholds for statistical significance (women, F-value 0.03 and men 0.25 with 1 and 381 degrees of freedom).

Moreover, self-employed workers are more likely to have irregular working hours (statistically significant bivariate Anova test results not shown). This particular characteristic is reflected separately in the empirical specification (see below).

This is a basic trait of the collective approach to household modeling. The Pareto optimal character of the outcome is assumed, without specifying a particular solution concept.

Children are allowed to start pre-primary school on the first of five entry moments (after holiday periods) after they have reached the age of 30 months. Hence, many children enter pre-primary school slightly before their third birthday.

In some economic sectors, collective agreements allow for longer career breaks (up to five years). Furthermore, it is interesting to know that the benefit given during career breaks is considerably lower than the benefit for parental leave.

Another issue is the endogeneity of wages. We have instrumented the individual (log) wages using third order polynomials for age, a set of education dummies, a set of living region dummies, a dummy variable that indicates whether a person is an entrepreneur and family size. Because the data did not provide us with a good instrument, the exogenous wage variation that is predicted is entirely driven by the functional form that is chosen. Moreover, the SUR estimation results yielded rather similar results and, therefore, we use the observed wage rates instead of the instrumented wage rates in this paper.

If we would separately estimate the first and second stage model this would yield incorrect residuals, because they are computed from the instruments rather than the original variables (Wooldridge 2009). All statistics computed from those residuals would therefore be incorrect as well (i.e. variances, estimated standard errors, etc.). By using the STATA ivreg2 routine described in Baum et al. (2007) we obtain standard errors robust to the violation mentioned above.

For the sake of robustness, we also tested if α 4 · β 6 = α 6 · β 4 and if α 5 · β 6 = α 6 · β 5 and found similar results (i.e. \(\chi_{0.01}^{2}=10.11\) for (1) and \(\chi_{0.01}^{2}=0.54\) for (2)).

We do not include child variables as preference factors, such as the number of pre-school children and family size, as they are correlated with the child care benefits and the child care demand included in \(\widetilde{y}_{n}\). We note that these child variables are insignificant when we include them in the labor supply functions, and this is likely caused by the \(\widetilde{y}\) variable that captures this effect.

For these predictions we used the price of formal child care which is on average 2.77 euro for the households in our sample.

References

Apps PF, Rees R (1997) Collective labor supply and household production. J Polit Econ 105:178–190

Baum C, Schaffer M, Stillman S (2007) Enhanced routines for instrumental variables/gmm estimation and testing. Boston College Working Paper in Economics

Beblo M (1999) Intrafamily time allocation: a panel-econometric analysis. In: Merz J, und Ehling M (Hrsg.) Time use-research, data and policy. Baden-Baden, pp 473–489

Becker GS (1991) A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Bergstrom T (1996) Economics in a family way. J Econ Lit 34(4):1903–1934

Blundell R, Chiappori PA, Meghir C (2005) Collective labour supply with children. J Polit Econ 113:1277–1306

Blundell R, MaCurdy T (1998) Labour supply: a review of alternative approaches. IFS Working Papers W98/18, Institute for Fiscal Studies

Borjas GJ (2002) The wage structure and the sorting of workers into the public sector. NBER Working Papers 9313, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc

Bourguignon F (1999) The cost of children: may the collective approach to household behavior help? J Popul Econ 12(4):503–521

Browning M, Bourguignon F, Chiappori PA, Lechene V (1994) Incomes and outcomes: a structural model of within household allocation. J Polit Econ 102(6):1067–1096

Browning M, Chiappori PA (1998) Efficient intra-household allocations: a general characterization and empirical tests. Econometrica 66(6):1241–78

Browning M, Chiappori PA, Lechene V (2006) Collective and unitary models: a clarification. Rev Econ Household 4:5–14

Cahuc P, Zylberberg A (2005) Labor economics. MIT Press, Cambridge

Cameron AC, Trivedi PK (2005) Micro econometrics—methods and applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Chiappori PA (1988) Rational household labor supply. Econometrica 56(1):63–90

Chiappori PA (1992) Collective labor supply and welfare. J Polit Econ 100:437–467

Chiappori PA (1997) Introducing household production in collective models of labor supply. J Polit Econ 105:191–209

Chiappori PA, Fortin B, Lacroix G (2002) Marriage market, divorce legislation, and household labor supply. J Polit Econ 110(1):37–72

Chiuri M (1999) Intra-household allocation of time and resources: empirical evidence of italian households with young children. CSEF Working Papers, no. 15

Couprie H (2007) Time allocation within the family: welfare implications of life in a couple. Econ J 117:287–305

Dauphin A, El Lahga AR, Fortin B, Lacroix G (2011) Are children decision-makers within the household? Econ J, 121(553):871–903

Donni O (2008) Household behavior and family economics. In: Zhang W-B (ed) The encyclopedia of life support systems. Publishers, Oxford

Evers M, de Mooij R, van Vuuren D (2005) What explains the variation in estimates of labour supply elasticities? CPB Discussion Paper

Ghysels J (2005) Holding the pencil or buying paint: parental childcare versus children’s need for extra income: the case of Belgium, Denmark and Spain. Rev Econ Household 3(3):269–289

Ghysels J, Debacker M (2007) Zorgen voor kinderen in Vlaanderen: een dagelijkse evenwichtsoefening translated: taking care of children in Flanders: a daily balance test. Acco publisher

Kapan T (2009) Essays on household bargaining. Unpublished dissertation, Columbia University

Kesenne S (1983) Substitution in consumption: an application of the allocation of time. Eur Econ Rev 2:231–239

Lundberg S, Pollak R (1993) Separate spheres bargaining and the marriage market. J Polit Econ 101(6):988–1010

Lundberg S, Pollak R, Wales TJ (1997) Do husbands and wives pool their resources? Evidence from the U.K. child benefit. J Hum Resour 32(3):463–480

Pagan AR, Hall D (1983) Diagnostic tests as residual analysis. Econom Rev 2:159–218

Rapoport B, Sofer C, Solaz A (2011) Household production in a collective model: some new results. J Popul Econ 24(1)

Thomas D (1990) Intra household resource allocation: an inferential approach. J Hum Resour 25(4):635–664

UNICEF (2008) The child care transition: a league table of early childhood education and care in economically advanced countries. United Nations Publications, New York

Vermeulen F (2002) Collective household models: principles and main results. J Econ Surv 16(4):534–564

Vermeulen F (2005) And the winner is... An empirical evaluation of unitary and collective labour supply models. Empir Econ 30(3):711–734

Wooldridge JM (2009) Instrumental variables and two stage least squares. In: Introductory econometrics: a modern approach, 4th edn, chapter 15. South-Western Cengage Learning, Mason, pp 506–545

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Pierre-André Chiappori, the editor and one anonymous referee for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

In this appendix, we show that productive efficiency requires the individual child care supply functions to depend on wages, just like labor supply. Let us consider the Lagrangian maximand \(\mathcal{L}\) using the maximization program in Eq. 5, i.e. \(\max_{h^{s},c^{s}}U^{s}(u^{s}(X^{s},1-c^{s}-h^{s}),H,Q)\). By assuming interior solutions, we can disregard the time constraints so that the Lagrange multiplier is attributed to the budget constraint \(X^{s}=w_{s}\cdot h^{s}+\rho^{s}\). The first order conditions then write:

From \(\frac{\partial\mathcal{L}}{\partial h^{s}}\) and \(\frac{\partial\mathcal{L}}{\partial c^{s}}\) it follows that the disutility of one time-unit of paid labor is equal to that of one time-unit of child care, in the sense that both have an equal and negative impact on the remaining leisure time. Consequently, we have that \(-\lambda w_{s}=\frac{\partial U^{s}}{\partial H}\frac{\partial H}{\partial c^{s}}\) and so the marginal utility contribution of individual child care time equals the marginal utility contribution of labor time in the optimum. As such (and in our specific case of an interior solution) the exogenous individual wage rate determines both the optimal amount of working time and care time.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Van Klaveren, C., Ghysels, J. Collective Labor Supply and Child Care Expenditures: Theory and Application. J Labor Res 33, 196–224 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-011-9127-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-011-9127-4