Abstract

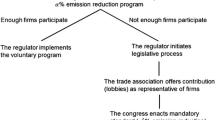

This paper focuses on a type of voluntary pollution abatement agreement (VA) in which the regulator offers regulatory relief for the participating firm in exchange for environmental improvements. If the regulator does not have statutory authority to provide regulatory relief, the VA can leave the firm more vulnerable to legal challenges through citizen lawsuits. I use a model of negotiated VAs to examine the impact of citizen enforcement on the likelihood of an agreement and on the outcome of a VA. The findings indicate that both the probabilities of enforcement by the regulatory agency and of private enforcement through a citizen lawsuit affect the likelihood of a VA and the level of abatement when an agreement is reached. A VA can result in higher abatement and net social benefits than regulation if the probability of private enforcement and accompanying costs are high and the probability of agency enforcement is low.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A third type of voluntary arrangements usually mentioned in this context is a unilateral commitment, in which a polluter develops initiatives without any regulatory involvement. Given their unilateral nature, it is not clear that they can be considered a voluntary “agreement.”

A recent review of trends in enforcement indicators suggests that EPA budgets and staffing levels have declined (in real terms) over time, and that only a fraction of regulated entities are subject to compliance monitoring or to penalties when noncompliant (Gray and Shimshack 2011).

The regulator may offer regulatory relief despite lacking the authority to do so because a private lawsuit is not certain and because the resulting abatement level may nevertheless yield a higher net benefit than what can be expected from imperfect enforcement.

This is generally not relevant for public voluntary programs to the extent that they are not legally binding and usually offer public recognition or technical assistance rather than regulatory relief, hence shielding the EPA and firms from legal action (Lyon and Maxwell 2004). However, citizen enforcement and the issues raised here for negotiated agreements would apply to public voluntary programs as well if they offered polluters a waiver from regulatory enforcement.

Although opportunities for involvement of private groups in environmental enforcement are increasing in Europe, citizen suit cases remain relatively infrequent because many national legal systems have traditionally restricted standing for environmental nongovernmental organizations (Kelemen 2006).

An agency decision not to prosecute, no matter how well founded, will not bar a citizen suit.

Note that the abatement level \(a\) is observable, and thus the regulator can verify whether the firm follows through on the negotiated agreement. The focus here is on the conditions that lead to a VA and on the resulting abatement levels. Hence I assume that the firm complies with the conditions of the agreement. This is consistent with the behavior of firms who enter this type of VAs in practice.

An alternative modeling approach would allow the private group to participate in the negotiation of the VA. All else equal, the abatement level resulting from the VA would be higher, since the private group would negotiate for more abatement. On the other hand, one can imagine that if there is an agreement and a VA is the equilibrium outcome of the negotiation between the regulator, the firm, and the environmental group, the threat of a lawsuit given a VA would disappear. Firms could only be sued in the absence of an agreement. Thus this is a different way of incorporating private group participation in a VA. Given that the focus here is on the threat of a suit when there is a VA, this alternative is left for further research.

To keep the contest model tractable, I have abstracted from the possibility that the private group may receive reimbursement for its legal expenditures if it wins the suit. See Baik and Shogren (1994) for a discussion of the efficiency properties of reimbursement rules.

Because civil penalties and litigation costs in citizen suits cases are generally high, I assume that \(F > ca_{S}\), that is, the cost from private enforcement exceed the compliance costs associated with agency enforcement.

I assume that \(a_{0} < a_{S}\), since it is reasonable to expect that the firm will choose less abatement than required by regulation.

The appendix is available at http://appliedecon.oregonstate.edu/langpapc.

It is straightforward to see that \({\partial a_V^{\min } }/{\partial p}={\left[ {NSB(a_S )-NSB(a_0 )} \right] }/{NS{{B}^{\prime }}(a_V^{\min })}>0\) since by construction \(NSB(\cdot )\) is increasing at \(a_V^{\min }\), and that \({\partial a_V^{\min } }/{\partial \gamma }=0.\)

It is easy to verify that if \(\pi (a) = 0\), which corresponds to the model without citizen suits, \(a_V^{\max } =a_S\) for \(p = 1\), so \(a_V^{\max } \ge a_V^{\min }\) for all \(p > 0\) and a VA is the equilibrium outcome for any positive enforcement probability (as in Segerson and Miceli 1998).

Note that a situation in which the regulator simply makes a take-it-or-leave-it offer to the firm, akin to a public voluntary program, corresponds to a special case in the model presented here in which the regulator has all the bargaining power, so that \(\alpha = 0\) (Segerson and Miceli 1998). In this case the regulator is essentially maximizing his payoff (NSB) subject to a participation constraint for the firm. Hence the outcome would be \(a_V =\min \{a_V^{\max } ,a^{*}\}.\)

References

Alberini, A., & Segerson, K. (2002). Assessing voluntary programs to improve environmental quality. Environmental and Resource Economics, 22, 157–184.

Baik, K. H., & Shogren, J. F. (1994). Environmental conflicts with reimbursement for citizen suits. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 27, 1–20.

Beavis, B., & Walker, M. (1983). Random wastes, imperfect monitoring, and environmental quality standards. Journal of Public Economics, 21, 377–387.

Blackman, A., & Mazurek, J. (2001). The cost of developing site-specific environmental regulations: Evidence from EPA’s project XL. Environmental Management, 27(1), 109–121.

Boyd, J., Krupnick, A. J., & Mazurek, J. (1998). Intel’s XL Permit: A Framework for Evaluation. Discussion Paper 98–11. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

Caldart, C. C., & Ashford, N. A. (1999). Negotiation as a means of developing and implementing environmental and occupational health and safety policy. The Harvard Environmental Law Review, 23, 141–202.

Dawson, N. L., & Segerson, K. (2008). Voluntary agreements with industries: Participation incentives with industry-wide targets. Land Economics, 84(1), 97–114.

Delmas, M., & Mazurek, J. (2004). A transaction cost perspective on negotiated agreements: The case of the USEPA XL programme. In A. Baranzini & P. Thalmann (Eds.), Voluntary approaches in climate policy. New horizons in environmental economics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Fadil, A. (1985). Citizen suits against polluters: Picking up the pace. Harvard Environmental Law Review, 9(1), 23–84.

Fleckinger, P., & Glachant, M. (2011). Negotiating a voluntary agreement when firms self-regulate. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 62, 41–52.

Glachant, M. (2007). Non-binding voluntary agreements. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 54, 32–48.

Gray, W. B., & Shimshack, J. P. (2011). The effectiveness of environmental monitoring and enforcement: A review of the empirical evidence. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 5(1), 3–24.

Heyes, A. G. (1997). Environmental regulation by private contest. Journal of Public Economics, 63, 407–428.

Heyes, A. G., & Rickman, N. (1999). Regulatory dealing—revisiting the Harrington Paradox. Journal of Public Economics, 72, 361–378.

Heyes, A. G. (2000). Implementing environmental regulation: Enforcement and compliance. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 17(2), 107–129.

Heyes, A. G., & Maxwell, J. W. (2004). Private versus public regulation: Political economy of the international environment. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 48, 978–996.

Innes, R. (2006). A theory of consumer boycotts under symmetric information and imperfect competition. Economic Journal, 116(511), 355–381.

Kaplow, L., & Shavell, S. (1994). Optimal law enforcement with self-reporting of behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 102, 583–606.

Kelemen, R. D. (2006). Suing for Europe. Adversarial legalism and European governance. Comparative Political Studies, 39(1), 101–127.

Khanna, M. (2001). Non-mandatory approaches to environmental protection. Journal of Economic Surveys, 15(3), 291–324.

Langpap, C., & Junjie, W. (2004). Voluntary conservation of endangered species: When does no regulatory assurance mean no conservation? Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 47, 453–457.

Langpap, C. (2007). Pollution abatement with limited enforcement power and citizen suits. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 31(1), 57–81.

Langpap, C. (2008). Self-reporting and private enforcement in environmental regulation. Environmental and Resource Economics, 40, 489–506.

Langpap, C., & Shimshack, J. (2010). Public and private environmental enforcement: Substitutes or complements? Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 59, 235–249.

Lyon, T. P., & Maxwell, J. W. (2004). Corporate environmentalism and public policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lyon, T. P., & Maxwell, J. W. (2008). Corporate social responsibility and the environment: A theoretical perspective. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 2(2), 240–260.

Lyon, T. P., & Maxwell, J. W. (2011). Greenwash: Corporate environmental disclosure under threat of audit. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 20, 3–41.

Mank, B. C. (1998). The environmental protection agency’s project XL and other regulatory reform initiatives: The need for legislative authorization. Ecology Law Quarterly, 25(11), 1–88.

Manzini, P., & Mariotti, M. (2003). A bargaining model of voluntary environmental agreements. Journal of Public Economics, 87, 2725–2736.

Marcus, A. A., Geffen, D. A., & Saxton, K. (2002). Reinventing environmental regulation. Lessons from project XL. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

Marcus, A. A., Geffen, D. A., & Saxton, K. (2005). Cooperative environmental regulation: Examining project XL. In T. de Bruijn & V. Norberg-Bohm (Eds.), Industrial transformation: Environmental policy innovation in the United States and Europe. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Maxwell, J. M., Lyon, T. P., & Hackett, S. C. (2000). Self-regulation and social welfare: The political economy of corporate environmentalism. Journal of Law and Economics, 43(2), 583–618.

McEvoy, D. M., & Stranlund, J. K. (2010). Costly enforcement of voluntary environmental agreements. Environmental and Resource Economics, 47, 45–63.

Montero, J. P. (2002). Prices versus quantities with incomplete enforcement. Journal of Public Economics, 85, 435–454.

Mookherjee, D., & Png, I. P. L. (1994). Marginal deterrence in enforcement of law. Journal of Political Economy, 102, 1039–1066.

Mrozek, J. R., & Keeler, A. G. (2004). Pooling of uncertainty: Enforcing tradable permits regulation when emissions are stochastic. Environmental and Resource Economics, 29, 459–481.

Naysnerski, W., & Tietenberg, T. (1992). Private enforcement of federal environmental law. Land Economics, 68, 28–48.

Segerson, K., & Miceli, T. J. (1998). Voluntary environmental agreements: Good or bad news for environmental protection? Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 36, 109–130.

Sinclair-Desgagne, B., & Gozlan, E. (2003). A theory of environmental risk disclosure. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 45, 377–393.

Smith, K. M. (2004). Who is suing whom: A comparison of government and citizen suit environmental enforcement actions brought under EPA-administered statutes, 1995–2000. Columbia Journal of Environmental Law, 29(2), 359–397.

Thompson, B. H., Jr. (2000). The continuing innovation of citizen enforcement. University of Illinois Law Review, 2000, 185–237.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Langpap, C. Voluntary agreements and private enforcement of environmental regulation. J Regul Econ 47, 99–116 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-014-9265-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-014-9265-8