Abstract

Anecdotal evidence suggests that journalists and bureaucrats in some countries are killed when they try to blow the whistle on corruption. We demonstrate in a simple game-theoretical model how murders can serve as an enforcer of corrupt deals under certain regime assumptions. Testing the main implications in an unbalanced panel of 179 countries observed through four periods, we find that corruption is strongly related to the incidence of murders of journalists in countries with almost full press freedom. While our results provide evidence that journalists are killed for corrupt reasons, they also suggest that some countries may have to go through quite violent periods when seeking to secure full freedom of the press.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The year of 2015 was only slightly better for journalists than previous years, while 2007 tops the list with 90 confirmed murders.

Table 1 contains only two murders of journalists who were investigating corrupt private deals, which would probably be uncovered by less corrupt officials. A positive correlation between private and public corruption is consistent with the existence of a “culture of corruption” within a country.

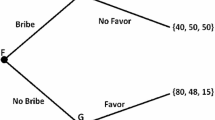

In the remainder of the paper, the briber will always be called the ‘firm’, neglecting internal principal-agent problems in firms. The recipient is always called the ‘bureaucrat’.

The role of press freedom has been discussed extensively in the literature, but in other contexts. See, e.g., Besley and Prat (2006) for an analysis of media capture in democracies, Leeson (2008) for the media’s role in generating political knowledge among the public, Gentzkov and Shapiro (2008) for a discussion of competition in the media, Djankov et al. (2003) for a discussion of media ownership, and Enikolopov and Petrova (2016) for a survey of the empirical literature on media capture. Most directly related to our paper is Frey and Torgler (2013), who explore the determinants of the murder of politicians.

A third reason can be seen in the fact that according to Orme (1998), official investigations of journalist murders tend to be slow and ineffective.

The corruption scale might be unstable in two different ways. First, when the mid-point of the scale slides over time, in which case the inclusion of period dummies would take care of any spurious effects. We include such period dummies even while noting that it is not likely that the scale of the CPI slides over time, since it is bounded between 1 and 10. Second, if the scale stretches or contracts over time, our estimates would be biased since scores would not be comparable across periods. However, we note that countries at either end of the scale, which we would strongly expect to have stable scores, do stay stable over time. At the high end of the scale, for example, neither Denmark nor Finland has had any corruption cases brought to court during this period. These ‘super-clean’ countries therefore anchor the scale at the upper end. At the lower end, a country like Kenya, which is known to have had very stable (and poor) institutions throughout the period, has also had a stable corruption score. Even though it may constitute a minor problem that a larger number of poor and highly corrupt countries were gradually included in the CPI since 1995, we take this to mean that countries such as Kenya have approximately acted as an anchor at the bottom level of the index. We take this as evidence that the ‘length’ of the CPI scale has not fluctuated or changed substantially. Yet it should be noted that because corruption enters in logarithms, the inclusion of period fixed effects implicitly means that the corruption measure is “de-meaned” by period.

It has to be kept in mind that both the CPI and ICRG index, our measures of corruption, are larger in less corrupt countries; see the negative sign in Table 3.

We note that a more standard choice would be to cluster the standard errors at the country level. However, because we have a number of countries with only one observation, i.e. T < 2 for a significant part of our sample, it is unclear if clustered standard errors are likely to be smaller or larger. We observe when clustering the standard errors that they become smaller for our main variables and therefore prefer to control directly for autocorrelation as the more conservative or the two tests. The results with clustered standard errors are of course available upon request.

We assume that θ is independent. Endogenizing θ to depend on k would arguably bring the model closer to reality. However, assuming that θ is decreasing in k without implying full convergence to sub-game perfect Nash equilibria with either θ = 0 or k = 0 (which would imply θ = 0) does not, in the absence of absurd (death-wish-like) behavioral assumptions, yield qualitatively different theoretical implications. We have therefore kept the model simple by assuming independence.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2006). Economic backwardness in political perspective. American Political Science Review, 100, 115–131.

Aidt, T. (2003). Economic analysis of corruption: a survey. Economic Journal, 113, F632–F652.

Besley, T., & Prat, P. (2006). Handcuffs for the grabbing hand? media capture and government accountability. American Economic Review, 96, 720–736.

Bjørnskov, C. (2011). Combating corruption: on the interplay between institutional quality and social trust. Journal of Law and Economics, 54, 135–159.

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14, 63–82.

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2010). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143, 67–101.

Committee to Protect Journalists. (2016). http://cpj.org (March 2016).

Coyne, C. J., & Leeson, P. T. (2009). Media as a mechanism of institutional change and reinforcement. Kyklos, 62, 1–14.

Djankov, S., McLiesh, C., Nenova, T., & Shleifer, A. (2003). Who owns the media? Journal of Law and Economics, 46, 341–381.

Dreher, A., Kotsogiannis, C., & McCorriston, S. (2007). Corruption around the world: evidence from a structural model. Journal of Comparative Economics, 35, 443–466.

Dreher, A., Kotsogiannis, C., & McCorriston, S. (2009). How do institutions affect corruption and the shadow economy? International Tax and Public Finance, 16, 773–796.

Enikolopov, R., & Petrova, M. (2016). Media capture: empirical evidence. In S. P. Anderson, D. Strömberg, & J. Waldfogel (Eds.), Handbook of media economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Freedom House. (2012). Freedom in the world 2012. The annual survey of political rights and civil liberties. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Frey, B. S., & Torgler, B. (2013). Politicians: be killed or survive. Public Choice, 156, 357–386.

Friedrich, R. (1982). In defense of multiplicative terms in multiple regression equations. American Journal of Political Science, 26, 797–833.

Gentzkov, M., & Shapiro, J. M. (2008). Competition and truth in the market for news. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22, 133–154.

Gwartney, J., Lawson, R., & Hall, J. (2014). Economic freedom of the world 2014 annual report. Vancouver: Fraser Institute.

Heckman, J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47, 153–161.

Heston, A., Summers, R., & Aten, B. (2012). Penn world table version 7.1. Center for International Comparisons of Production, Income and Prices, University of Pennsylvania.

ICRG. (2012). International country risk guide. Syracuse: The PRS Group.

Knack, S., & Langbein, L. (2010). The worldwide governance indicators and tautology: six, one, or none? Journal of Development Studies, 46, 350–370.

Lambsdorff, J. G. (2002). How confidence facilitates illegal transactions. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 61, 829–854.

Leeson, P. T. (2008). Media freedom, political knowledge, and participation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22, 155–169.

Leeson, P. T., & Coyne, C. J. (2007). The reformers’ dilemma: media, policy ownership, and reform. European Journal of Law and Economics, 23, 237–250.

McMilan, J., & Zoido, P. (2004). How to Subvert Democracy: Montesinos in Peru. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18, 69–92.

Montinola, G. R., & Jackman, R. W. (2002). Sources of corruption: a cross-country study. British Journal of Political Science, 32, 147–170.

Muller, E. N., & Weede, E. (1990). Cross-national variation in political violence: a rational action approach. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 34, 624–651.

Orme, W. R, Jr. (1998). The meaning of the murders. In N. J. Woodhull & R. W. Snyder (Eds.), Journalists in Peril. New Brunswick: Transaction.

Reporters without Borders. (2016). http://rsf.org/ (March 2016).

Richards, D. L., Gelleny, R., & Sacko, D. (2001). Money with a mean streak? Foreign economic penetration and government respect for human rights in developing countries. International Studies Quarterly, 45, 219–239.

Rubenfeld, S. (2011). Many journalists killed in 2010 covered corruption. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved Jan 4, 2011.

Skarbek, D. (2014). The social order of the underworld: how prison gangs govern the American penal system. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tavits, M. (2007). Clarity of responsibility and corruption. American Journal of Political Science, 51, 218–229.

Transparency International. (2015). Website and database. https://www.transparency.org/ (November 2015).

Treisman, D. (2007). What have we learned about the causes of corruption from ten years of cross-national empirical research? Annual Review of Political Science, 10, 211–244.

Vreeland, J. R. (2008). The effect of political regime on civil war: unpacking anocracy. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52, 401–425.

Warren, M. (2006). Democracy and deceit: regulating appearances of corruption. American Journal of Political Science, 50, 160–174.

World Bank. (2015). World development indicators. CD-ROM and on-line database. Washington: The World Bank.

Yavas, C. (2007). The ghost of corruption. B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 7, article 38.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christoph Engel, Bruno Frey, Oliver Kirchkamp, Guido Mehlkop, Philipp Schröder, Bill Shughart, participants of the fourth political economy workshop in Dresden, the annual meetings of the European Public Choice Society (Rennes), seminars at the New Economic School, the GSBC in Jena, Wake Forest University and the University of Stellenbosch, and two anonymous reviewers at this journal for commenting on earlier versions. All remaining errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Proofs of propositions 1–4

Appendix: Proofs of propositions 1–4

First, Proposition 1 follows directly from differentiating Eq. 4 by legal quality and noting that N and M both depend positively on the degree of press freedom, which can be described as (N–M) ~ θ: \( \frac{{dK^{ * } }}{d\lambda } = f\left( \cdot \right)\frac{{w - w_{out} - N + M}}{{\left( {1 - \lambda } \right)^{2} }}k^{ * } \).

Proposition 2 similarly follows from differentiating Eq. 4 by θ and noting that the derivates N θ and M θ both are positive. \( \frac{{dK^{ * } }}{d\theta } = f\left( \cdot \right)\frac{{N_{\theta } - M_{\theta } }}{{\left( {1 - \lambda } \right)}}k^{ * } + K^{ * } \frac{1}{{k^{ * } w}} \).Footnote 11 The implication that this becomes more likely to be positive is given jointly by Eqs. 4 and 4.

Proposition 3 is a consequence of differentiating Eq. 4 by w. This yields \( \frac{{dK^{ * } }}{dw} = f\left( \cdot \right)\frac{\lambda }{{\left( {1 - \lambda } \right)}}k^{ * } - K^{ * } \frac{{k^{ * } }}{w} \).

Finally, Proposition 4 follows from noting that N and M both depend positively on the degree of press freedom as in Proposition 1. With a sufficient correlation between λ and θ such that the latter is a function of the former, the full effect becomes ambiguous with a peak at some intermediary level.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bjørnskov, C., Freytag, A. An offer you can’t refuse: murdering journalists as an enforcement mechanism of corrupt deals. Public Choice 167, 221–243 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-016-0338-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-016-0338-3