Abstract

Objectives

The federal sentencing guidelines constrain decision makers’ discretion to consider offenders’ life histories and current circumstances, including their histories of drug use and drug use at the time of the crime. However, the situation is complicated by the fact that judges are required to take the offender’s drug use into account in making bail and pretrial detention decisions and the ambiguity inherent in decisions regarding substantial assistance departures allows consideration of this factor. In this paper we build upon and extend prior research examining the impact of an offender’s drug use on sentences imposed on drug trafficking offenders.

Methods

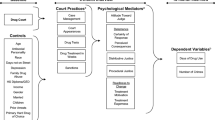

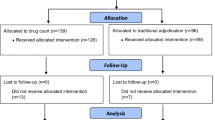

We used data from three U.S. District Courts and a methodologically sophisticated approach (i.e., path analysis) to test for the direct and indirect (i.e., through pretrial detention and receipt of a substantial assistance departure) effects of an offender’s drug use history and use of drug at the time of the crime, to determine if the effects of drug use varies by the type of drug, and to test for the moderating effect of type of crime.

Results

We found that although the offender’s history of drug use did not affect sentence length, offenders who were using drugs at the time of the crime received longer sentences both as a direct consequence of their drug use and because drug use at the time of the crime increased the odds of pretrial detention and increased the likelihood of receiving a substantial assistance departure. We also found that the effects of drug use varied depending on whether the offender was using crack cocaine or some other drug and that the type of offense for which the offender was convicted moderated these relationships.

Conclusions

Our findings illustrate that there is a complex array of relationships between drug use and key case processing decisions in federal courts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The data used in this study are from the pre-Booker time period, when the guidelines were mandatory. However, our analysis of the effect of drug use on sentencing is quite relevant to the post-Booker era, given that judges now have more discretion to consider offenders’ life circumstances and backgrounds.

Our data do not contain information on clinical diagnoses of drug abuse or dependence, only whether the defendant had used illegal drugs. We therefore use the term “drug use” throughout the paper. This limitation is discussed further in the "Discussion" section.

Moreover, if some judges adopt the first perspective (and, as a result, sentence offenders who use or abuse drugs more harshly) but others adopt the second (and sentence those who use or abuse drugs more leniently), the positive and negative effects of the drug use variables on case outcomes may cancel each other out.

We do not model the prison/no prison decision because the two drug use variables did not have statistically significant effects on the likelihood of imprisonment in our model without the two mediating variables. According to the classic strategy on mediation analysis (see Baron and Kenny 1986), the first step in modeling a mediated relationship is to estimate a model without possible mediating variables. The analysis only proceeds to the next step if there is a direct relationship between the variables of interest and the dependent variable. Because there were no direct effects on the likelihood of imprisonment, we could not logically test for the mediating effects of pretrial detention or substantial assistance departure.

The decision to exclude offenders not sentenced to prison raises a potential sample selection bias issue. To correct for this potential bias, we followed suggestions by Bushway et al. (2007) regarding the use of the Heckman two-step procedure. However, consistent with most sentencing research, we failed to locate the exclusion restriction and estimated the inverse Mills ratio without the exclusion criteria. When we attempted to model our outcome with the Lambda term included, we found that the Lambda term was highly correlated with the presumptive sentence (r = −0.87, p = .000) and more importantly the condition index was 36.18, which goes well beyond the recommended range. For these reasons, we use the uncorrected estimates and care must be taken in interpreting the results in that respect.

Offenders who were using hard drugs at the time of the crime by definition have a history of hard drug use, which was measured as evidence that the offender had “ever” used the specified drugs. Our history of hard drug use variables therefore differentiate among offenders who had used hard drugs at some point in their lives but were not using drugs at the time of the crime, offenders who were using hard drugs at the time of the crime, and offenders who had never used hard drugs.

We first ran the models using a set of dummy variables (violent, drug, fraud, weapons, immigration, and other offenses). However, a series of model specifications indicated that this was unnecessarily specific and therefore undermined the principle of model parsimony, which is an important concern of path analysis.

It is important to note that our models do not control for whether the offender received an upward departure or a judge-initiated downward departure. Because there were only 13 upward departure cases (and thus upward departures did not constitute a meaningful outcome), we eliminated these cases from the analysis. Our decision to use substantial assistance departure but not judicial departure as a mediating variable reflects the fact that the decision to file a motion for a substantial assistance departure is an important earlier case processing outcome; prosecutors have sole discretion to file a motion for this type of departure (in many cases as a part of plea negotiations) and therefore judges have limited control over this outcome (although they must approve the motion). By contrast, a judicial departure typically is given during the final sentencing process; as such, it is not necessarily an earlier case processing outcome. The fact that we do not control for judicial departure status means that the effects of the drug use/history variables are the effects estimated at the final sentencing decision both within and outside the guideline ranges.

Path analysis is a more appropriate analytical technique than a regression-based mediation technique. It provides a specific indirect effect size, which is difficult to calculate in the regression-based mediation technique. In addition, our fifth hypothesis, which focuses on moderated mediation, adds more complexity and therefore requires a more sophisticated analytical approach.

Maximum likelihood (ML) estimation is one of the most widely used estimators in the path analytic approach; it assumes that all the variables in the model will follow multivariate normal distributions. As a result, binary variables typically were not included in path models, before WLS (Weighted Least Squares) appeared as an alternative model estimator. However, Muthén et al. (1997) reported that WLS was found to be inferior to WLSMV estimation. With regard to the use of the theta parameterization, M-plus provides two tests for the significance of indirect effects: the delta and the theta tests. Theta parameterization must be selected when categorical endogenous variables are employed along with a continuous dependent variable (Muthen and Muthen 1998: 2011).

The determination of model fit in path models or SEM is not as straightforward as it is with other statistical approaches. It is recommended that various model-fit criteria be used in combination to assess overall model fit. Model fit criteria and acceptable fit interpretation are as follows; the probability of Chi square test should be p > 0.05. RMSEA should have at least a value of 0.05 to 0.08. CFI and TLI should have values close to 0.90 or 0.95. The chi-square model-fit criterion is sensitive to sample size because as sample size increases, the chi-square statistic has a tendency to indicate a significant probability level. Furthermore, the chi-square statistic is also sensitive to departures from multivariate normality of the observed variables. For these reasons, studies which analyze large samples with ordinal endogenous variables in the model rely on more robust model fit indicators such as RMSEA (Bollen 1989).

One anonymous reviewer pointed out that our measure of non-drug offense might be problematic, since several different offenses comprise the non-drug category and there may be important differences in the ways that drug use/abuse affects these crimes. Following this reviewer’s suggestion, we attempted to compare drug offenses with a non-drug category that excluded violent crimes. One of the consistent results was that the indirect effects of both current crack use and other drug use via pretrial detention were substantially reduced for non-drug offenders. This finding raises a possibility that some of the statistically significant indirect effects through pretrial detention for non-drug offenders in Table 5 resulted from the effects of violent crime. The other comparisons (i.e. drug v. violent offense or drug v. fraud) were not feasible due to the small number of offenders in these categories who received substantial assistance departures.

One anonymous reviewer pointed out that our estimates for the effects of drug use variables on pretrial detention may be biased due to an omitted variable bias. Even though our main measures are largely consistent with those of prior studies on pretrial detention, there still exists a possibility that the absence of some of the factors considered relevant to pretrial decision-making (i.e. evidence, health, length of residence) may have resulted in biased estimates. For that reason, our estimates need to be interpreted with caution.

References

Albonetti CA (1991) An integration of theories to explain judicial discretion. Soc Probl 38(2):247–266

Albonetti CA (1997) Sentencing under the federal sentencing guidelines: effects of defendant characteristics, guilty pleas, and departures on sentence outcomes for drug offenses, 1991–1992. Law Soc Rev 31(4):789–822

Albonetti CA (2002) The joint conditioning effect of defendant’s gender and ethnicity on length of imprisonment under the federal sentencing guidelines for drug trafficking/manufacturing offenders. J Gender Race Justice 6:39–60

Albonetti CA, Hauser RM, Hagan J, Nagel IH (1989) Criminal justice decision making as a stratification process: the role of race and stratification resources in pretrial release. J Quant Criminol 5(1):57–82

Ball SA (2005) Personality traits, problems, and disorders: clinical applications to substance use disorders. J Res Personality 39(1):84–102

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Person Soc Psych 51(6):1173–1182

Belenko S (1993) Crack and the evolution of anti-drug policy. Greenwood Press, Westport

Belenko S (2002) Drug courts. In: Leukefeld C, Tims F, Farabee D (eds) Treatment of drug offenders: policies and issues. Springer, New York City, pp 301–318

Belenko S, Peugh J (2005) Estimating drug treatment needs among state prison inmates. Drug Alcohol Dependence 77(3):269–281

Belenko S, Sung H-E, Swern A, Donhauser C (2008) Prosecutors and treatment diversion: The Brooklyn (NY) DTAP Program. In: Worrall JL, Nugent ME (eds) The changing role of the American prosecutor. State University of New York Press, Albany, pp 111–137

Belenko S, Houser K, Welsh W (2011) Understanding the impact of drug treatment in correctional settings. In: Petersilia J, Reitz K (eds) Oxford handbook on sentencing and corrections. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 463–491

Bollen KA (1989) Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley, New York

Brennan P (2006) Sentencing female misdemeanants: an examination of the direct and indirect effects of race/ethnicity. Justice Q 23(1):60–95

Bushway S, Johnson BD, Slocum L (2007) Is the magic still there? The use of the Heckman two-step correction for selection bias in criminology. J Quant Criminol 23(2):151–178

Chandler R, Fletcher B, Volkow N (2009) Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system: improving public health and safety. J Am Med Asso 301(2):183–190

Chiricos TG, Bales WD (1991) Unemployment and punishment: an empirical assessment. Criminology 29(4):701–724

Chiricos TG, Crawford C (1995) Race and imprisonment: a contextual assessment of the evidence. In: Hawkins DF (ed) Ethnicity, race, and crime: perspectives across time and place. State University of New York Press, Albany, pp 281–308

De Bellis MD (2002) Developmental traumatology: a contributory mechanism for alcohol and substance use disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 27(1–2):155–170

Deas D, St. Germaine K, Upadhyaya H (2006) Psychopathology in substance abusing adolescents: gender comparisons. J Substance Use 11(1):45–51

Demuth S (2003) Racial and ethnic differences in pretrial release decisions and outcomes: a comparison of Hispanic, black, and white felony arrestees. Criminology 41(3):873–907

Demuth S, Steffensmeier S (2004) Ethnicity effects on sentence outcomes in large urban courts: comparisons among white, black, and Hispanic defendants. Soc Sci Q 85(4):994–1011

Edwards JR, Lambert LS (2007) Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: a general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psych Methods 12(1):1–22

Elkins IJ, King SM, McGue M, Iacono WG (2006) Personality traits and the development of nicotine, alcohol, and illicit drug disorders: prospective links from adolescence to young adulthood. J Abnor Psych 115(1):26–39

Everett RS, Wojtkiewicz RA (2002) Difference, disparity, and race/ethnic bias in federal sentencing. J Quant Criminol 18(2):189–211

Hartley RD, Maddan S, Spohn C (2007) Prosecutorial discretion: an examination of substantial assistance departures in federal crack-cocaine and powder-cocaine cases. Justice Q 24(3):382–407

Hofer PJ, Blackwell KR, Ruback B (1999) The effect of the federal sentencing guidelines on inter-judge sentencing disparity. J Crim Law Criminol 90(1):239–322

Hopwood CJ, Morey LC, Sodol AE, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Ansell EB, McGlashan TH, Stout RL (2011) Pathological personality traits among patients with absent, current, and remitted substance abuse disorders. Addictive Behav 36(11):1087–1090

Hora PF, Schma WG, Rosenthal JTA (1999) Therapeutic jurisprudence and the drug treatment court movement: revolutionizing the criminal justice system’s response to drug abuse and crime in America. Notre Dame Law Rev 74:439–538

Inciardi JA, Martin SS, Butzin CA (2004) Five-year outcomes of therapeutic community treatment of drug-involved offenders after release from prison. Crime Delinq 50(1):88–107

Johnson BD, Betsinger S (2009) Punishing the “model minority:” Asian-American criminal sentencing outcomes in federal district courts. Criminology 47(4):1045–1090

Johnson BD, Ulmer JT, Kramer JH (2008) The social context of guidelines circumvention: the case of federal district courts. Criminology 46(3):737–784

Katz CM, Spohn C (1995) The effect of race and gender on bail outcomes: a test of an interactive model. Am J Crim Justice 19(2):161–184

Kautt PM (2002) Location, location, location: interdistrict and intercircuit variation in sentencing outcomes for federal drug-trafficking offenses. Justice Q 19(4):633–671

Kempf-Leonard K, Sample LL (2001) Have federal sentencing guidelines reduced severity? An examination of one circuit. J Quant Criminol 17(2):111–144

Kosten TR (1998) Addiction as a brain disease. Am J Psychi 155(6):711–713

Kramer JH, Steffensmeier D (1993) Race and imprisonment decisions. Sociol Q 34(2):357–376

Kramer JH, Ulmer JT (1996) Sentencing disparity and departures from guidelines. Justice Q 13(1):81–106

LaCasse C, Payne AA (1999) Federal sentencing guidelines and mandatory minimum sentences: do defendants bargain in the shadow of the judge? J Law Econ 42(1):245–269

LaFrenz C, Spohn C (2006) Who is punished more harshly? An examination of race/ethnicity, gender, age and employment status under the federal sentencing guidelines. Justice Res Pol 8(1):25–56

MacKinnon DP (2008) Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Erlbaum, Mahwah

Marlowe DB (2003) Integrating substance abuse treatment and criminal justice supervision. NIDA Science and Practice Perspectives 2:4–14

Mauer M and King RS (2007) Uneven justice: state rates of incarceration by race and ethnicity. The Sentencing Project, Washington, DC

Maxfield LD, Kramer JH (1998) Substantial assistance: an empirical yardstick gauging equity in current federal sentencing practice. U.S. Sentencing Commission, Washington, DC

Mumola C and Karberg J (2006) Drug use and dependence, state and federal prisoners, 2004. NCJ 213530. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC

Mustard DB (2001) Racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in sentencing: evidence from the U.S. federal courts. J Law Econ 44(1):285–314

Muthen LK, and Muthen BO (1998–2011). Mplus User’s guide Six Edition. Los Angeles, CA

Muthén BO, DuToit SHC, and Spisic D (1997) Robust inference using weighted least squares and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modeling with categorical and continuous outcomes. Unpublished technical report

Nagel IH, Schulhofer SJ (1992) A tale of three cities: an empirical study of charging and bargaining practices under the federal sentencing guidelines. South California Law Rev 66(1):501–566

Pasko L (2002) Villain or victim: regional variation and ethnic disparity in federal drug offense sentencing. Crim Justice Policy Rev 13(4):307–328

Pelissier B, Wallace S, O’Neil JA, Gaes GG, Camp S, Rhodes W, Saylor WG (2001) Federal prison residential drug treatment reduces substance use and arrests after release. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 27(2):315–337

Ruiz MA, Pincus AL, Schinka JA (2008) Externalizing pathology and the five-factor model: a meta-analysis of personality traits associated with antisocial personality disorder, substance use disorder, and their co-occurrence. J Person Disorders 22(4):365–388

Satel S (2007) The human factor. The American. Online publication at http://www.american.com/archive/2007/july-august-magazine-contents/the-human-factor-2

Schlesinger T (2005) Racial and ethnic disparities in pretrial criminal processing. Justice Q 22(2):170–192

Skeem J, Ecandela J, Louden J (2003) Perspectives on probation and mandated mental health treatment in specialized and traditional probation departments. Behav Sci Law 21(4):429–458

Spohn C (2000) Thirty years of sentencing reform: the quest for a racially neutral sentencing process. In: Criminal justice 2000, vol 3: policies, processes and decisions of the criminal justice system. Office of Justice Programs, Washington, DC

Spohn C (2005) Sentencing decisions in three U.S. district courts: testing the assumption of uniformity in the federal sentencing process. Justice. Res Policy 7(2):1–27

Spohn C (2009) Race, sex and pretrial detention in Federal Court: indirect effects and cumulative disadvantage. Kansas Law Rev 57:879–902

Spohn C, Belenko S (2013) Do the drugs, do the time? The effect of drug abuse on sentences imposed on drug offenders in three U.S. district courts. Crim Justice Behav 40(6):646–670

Spohn C, Fornango R (2009) U.S. attorneys and substantial assistance departures: testing for interprosecutor disparity. Criminology 47(3):813–846

Spohn C, Holleran D (2000) The imprisonment penalty paid by young, unemployed black and hispanic male offenders. Criminology 38(1):281–306

Stacey AM, Spohn C (2006) Gender and the social costs of sentencing: an analysis of sentences imposed on male and female offenders in three U.S. district courts. Berkeley J Crim Law 11:43–76

Steffensmeier D, Demuth S (2000) Ethnicity and sentencing outcomes in U.S. federal courts: who is punished more harshly? Am Sociol Rev 65(5):705–729

Steffensmeier D, Kramer JH, Streifel C (1993) Gender and imprisonment decisions. Criminology 31(3):411–446

Steffensmeier D, Ulmer JT, Kramer JH (1998) The interaction of race, gender, and age in criminal sentencing: the punishment cost of being young, black, and male. Criminology 36(4):763–798

Stith K, Cabranes JA (1998) Fear of judging: sentencing guidelines in the federal courts. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Sullum J (2003) H: the surprising truth about heroin addiction. Reason 35:32–40

Taxman FS, Thanner M (2004) Probation from a therapeutic perspective: results from the field. Contemp Issues Law 7(1):39–63

Taxman FS, Cropsey K, Melnick J, Perdoni M (2008) COD services in community correctional settings: an examination of organizational factors that affect service delivery. Behav Sci Law 26(4):435–455

Tonry M (1995) Malign neglect: race, crime, and punishment in America. Oxford University Press, New York

Tonry M (1996) Sentencing matters. Oxford University Press, New York City

Uhl GR (2004) Molecular genetic underpinnings of human substance abuse vulnerability: likely contributions to understanding addiction as a mnemonic process. Neuropharmacology 47(suppl 1):140–147

Uhl GR, Grow RW (2004) The burden of complex genetics in brain disorders. Archi Gen Psychi 61(3):223–229

Ulmer JT, Eisenstein J, Johnson B (2010) Trial penalties in federal sentencing: extra-guidelines factors and district variation. Justice Q 27(4):560–592

United States Sentencing Commission (2004) Fifteen years of guidelines sentencing: an assessment of how well the federal criminal justice system is achieving the goals of sentencing reform. Washington, DC

United States Sentencing Commission (2007) Cocaine and federal sentencing policy. United States Sentencing Commission, Washington, DC

United States Sentencing Commission (2008) Federal sentencing guidelines manual. West Publishing Co, St. Paul

Volkow N, Li TK (2005) The neuroscience of addiction. Nat Neurosci 8:1429–1430

Volkow N, Fowler J, Wang G-J, Swanson J, Telang F (2007) Dopamine in drug abuse and addiction: results of imaging studies and treatment implications. Archi Neurology 64:1575–1579

Weisselberg CD, Dunsworth T (1993) Inter-district variation under the guidelines: the trees may more significant than the forest. Fed Sent Rep 6(1):25–28

Wooldridge J (2002) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. The MIT Press, NY

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spohn, C.C., Kim, B., Belenko, S. et al. The Direct and Indirect Effects of Offender Drug Use on Federal Sentencing Outcomes. J Quant Criminol 30, 549–576 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-014-9214-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-014-9214-9