Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of maternal serum total Homocysteine (tHcy) and uterine artery (Ut-A) Doppler as predictors of preeclampsia (PE), intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and other complications related to poor placentation.

Patients and methods

A prospective cohort study was conducted on 500 women with spontaneous pregnancies. tHcy was measured at 15–19 weeks, and then, Ut-A Doppler was performed at 18–22 weeks of pregnancy.

Results

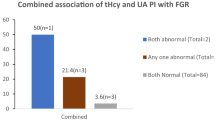

453 pregnant women completed the follow-up of the study. The tHcy and Ut-A resistance index were significantly higher in women who developed PE, IUGR, and other complications when compared to controls (tHcy: 7.033 ± 2.744, 6.321 ± 3.645, and 6.602 ± 2.469 vs 4.701 ± 2.082 μmol/L, respectively, p value <0.001 and Ut-A resistance index: 0.587 ± 0.072, 0.587 ± 0.053, and 0.597 ± 0.069 vs 0.524 ± 0.025, respectively, p value <0.001). The use of both tHcy assessment and Ut-A Doppler improved the sensitivity of prediction of PE relative to the use of each one alone (85.2 relative to 73.33 and 60%, respectively).

Conclusion

The use of elevated homocysteine and uterine artery Doppler screening are valuable in prediction of preeclampsia, IUGR, and poor placentation disorders.

ClincalTrial.gov ID

NCT02854501.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

19 March 2024

An Editorial Expression of Concern to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-024-07454-w

15 April 2024

An Editorial Expression of Concern to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-024-07491-5

References

Lopez-Quesada E, Vilaseca MA, Vela A, Lailla JM (2004) Perinatal outcome prediction by maternal homocysteine and uterine artery Doppler velocimetry. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 113(1):61–66. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2003.05.003

Kaymaz C, DemirA Bige O, Cagliyan E, Cimrin D, Demir N (2011) Analysis of perinatal outcome by combination of first trimester maternal plasma homocysteine with uterine artery Doppler velocimetry. Prenat Diagn 31(13):1246–1250. doi:10.1002/pd.2874

Palmer SK, Zamudio S, Coffin C, Parker S, Stamm E, Moore LG (1992) Quantitative estimation of human uterine artery blood flow and pelvic blood flow redistribution in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 80(6):1000–1006

Roberts JM, Cooper DW (2001) Pathogenesis and genetics of pre-eclampsia. Lancet 357(9249):53–56

Wang Y, Gu Y, Granger DN, Roberts JM, Alexander JS (2002) Endothelial junctional protein redistribution and increased monolayer permeability in human umbilical vein endothelial cells isolated during preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 186(2):214–220

Suzuki Y, Yamamoto T, Mabuchi Y, Tada T, Suzumori K, Soji T, Herbert DC, Itoh T (2003) Ultrastructural changes in omental resistance artery in women with preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189(1):216–221

Maged AM, ElNassery N, Fouad M, Abdelhafiz A, Al Mostafa W (2015) Third-trimester uterine artery Doppler measurement and maternal postpartum outcome among patients with severe pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstetr 131(1):49–53. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.03.045

Dodds L, Fell DB, Dooley KC, Armson BA, Allen AC, Nassar BA, Perkins S, Joseph KS (2008) Effect of homocysteine concentration in early pregnancy on gestational hypertensive disorders and other pregnancy outcomes. Clin Chem 54(2):326–334. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2007.097469

Yang Y, Luo Y, Yuan J, Tang Y, Xiong L, Xu M, Rao X, Liu H (2016) Association between maternal, fetal and paternal MTHFR gene C677T and A1298C polymorphisms and risk of recurrent pregnancy loss: a comprehensive evaluation. Arch Gynecol Obstet 293(6):1197–1211. doi:10.1007/s00404-015-3944-2

Kramer MS, Kahn SR, Rozen R, Evans R, Platt RW, Chen MF, Goulet L, Seguin L, Dassa C, Lydon J, McNamara H, Dahhou M, Genest J (2009) Vasculopathic and thrombophilic risk factors for spontaneous preterm birth. Int J Epidemiol 38(3):715–723. doi:10.1093/ije/dyp167

Yin Y, Zhang T, Dai Y, Zheng X, Pei L, Lu X (2009) Pilot study of association of anembryonic pregnancy with 55 elements in the urine, and serum level of folate, homocysteine and S-adenosylhomocysteine in Shanxi Province, China. J Am Coll Nutr 28(1):50–55

Chen H, Yang X, Lu M (2016) Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphisms and recurrent pregnancy loss in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 293(2):283–290. doi:10.1007/s00404-015-3894-8

Yajnik CS, Deshpande SS, Jackson AA, Refsum H, Rao S, Fisher DJ, Bhat DS, Naik SS, Coyaji KJ, Joglekar CV, Joshi N, Lubree HG, Deshpande VU, Rege SS, Fall CH (2008) Vitamin B12 and folate concentrations during pregnancy and insulin resistance in the offspring: the Pune Maternal Nutrition Study. Diabetologia 51(1):29–38. doi:10.1007/s00125-007-0793-y

Caforio L, Testa AC, Mastromarino C, Carducci B, Ciampelli M, Mansueto D, Caruso A (1999) Predictive value of uterine artery velocimetry at midgestation in low- and high-risk populations: a new perspective. Fetal Diagn Ther 14(4):201–205. doi:10.1159/000020921

Zamarian ACP, Araujo Júnior E, Daher S, Rolo LC, Moron AF, Nardozza LMM (2016) Evaluation of biochemical markers combined with uterine artery Doppler parameters in fetuses with growth restriction: a case–control study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 294(4):715–723. doi:10.1007/s00404-016-4024-y

Stubert J, Kleber T, Bolz M, Külz T, Dieterich M, Richter D-U, Reimer T (2016) Acute-phase proteins in prediction of preeclampsia in patients with abnormal midtrimester uterine Doppler velocimetry. Arch Gynecol Obstet 294(6):1151–1160. doi:10.1007/s00404-016-4138-2

Noguchi J, Tanaka H, Koyanagi A, Miyake K, Hata T (2015) Three-dimensional power Doppler indices at 18–22 weeks’ gestation for prediction of fetal growth restriction or pregnancy-induced hypertension. Arch Gynecol Obstet 292(1):75–79. doi:10.1007/s00404-014-3603-z

Uyar İ, Kurt S, Demirtaş Ö, Gurbuz T, Aldemir OS, Keser B, Tasyurt A (2015) The value of uterine artery Doppler and NT-proBNP levels in the second trimester to predict preeclampsia. Arch Gynecol Obstet 291(6):1253–1258. doi:10.1007/s00404-014-3563-3

Ducros V, Demuth K, Sauvant MP, Quillard M, Causse E, Candito M, Read MH, Drai J, Garcia I, Gerhardt MF (2002) Methods for homocysteine analysis and biological relevance of the results. J Chromatogr, B: Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci 781(1–2):207–226

Kurdi W, Campbell S, Aquilina J, England P, Harrington K (1998) The role of color Doppler imaging of the uterine arteries at 20 weeks’ gestation in stratifying antenatal care. Ultrasound Obstetr Gynecol 12(5):339–345. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0705.1998.12050339.x

Snydal S (2014) Major changes in diagnosis and management of preeclampsia. J Midwifery Women’s Health 59(6):596–605. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12260

Unterscheider J, O’Donoghue K, Malone FD (2015) Guidelines on fetal growth restriction: a comparison of recent national publications. Am J Perinatol 32(4):307–316. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1387927

Tikkanen M (2011) Placental abruption: epidemiology, risk factors and consequences. Actaobstetricia et gynecologicaScandinavica 90(2):140–149. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2010.01030.x

Onalan R, Onalan G, Gunenc Z, Karabulut E (2006) Combining 2nd-trimester maternal serum homocysteine levels and uterine artery Doppler for prediction of preeclampsia and isolated intrauterine growth restriction. Gynecol Obstet Invest 61(3):142–148. doi:10.1159/000090432

Flahault A, Cadilhac M, Thomas G (2005) Sample size calculation should be performed for design accuracy in diagnostic test studies. J Clin Epidemiol 58(8):859–862. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.12.009

Quere I, Bellet H, Hoffet M, Janbon C, Mares P, Gris JC (1998) A woman with five consecutive fetal deaths: case report and retrospective analysis of hyperhomocysteinemia prevalence in 100 consecutive women with recurrent miscarriages. Fertil Steril 69(1):152–154

Lopez-Quesada EL, Vilaseca MA, Gonzalez S (2000) Homocysteine and pregnancy. Medicinaclinica 115(9):352–356

Mignini LE, Latthe PM, Villar J, Kilby MD, Carroli G, Khan KS (2005) Mapping the theories of preeclampsia: the role of homocysteine. Obstet Gynecol 105(2):411–425. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000151117.52952.b6

Moat SJ, McDowell IF (2005) Homocysteine and endothelial function in human studies. Sem Vasc Med 5(2):172–182. doi:10.1055/s-2005-872402

Mascarenhas M, Habeebullah S, Sridhar MG (2014) Revisiting the role of first trimester homocysteine as an index of maternal and fetal outcome. J Pregnancy 2014:123024. doi:10.1155/2014/123024

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AMM: project development, data collection, and manuscript writing; HS: data collection; HM: data collection; ES: data collection; SA: manuscript writing and data collection; EO: data collection, data analysis, and manuscript writing; WD: manuscript writing; MK: manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maged, A.M., Saad, H., Meshaal, H. et al. Maternal serum homocysteine and uterine artery Doppler as predictors of preeclampsia and poor placentation. Arch Gynecol Obstet 296, 475–482 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4457-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4457-y