Abstract

The current financial crisis offers a unique opportunity to investigate the leading properties of market indicators in a stressed environment and their usefulness from a banking supervision perspective. One pool of relevant information that has been little explored in the empirical literature is the market for bank’s exchange-traded option contracts. In this paper, we first extract implied volatility indicators from the prices of option contracts on financial firms’ equity. We then examine empirically their ability to predict financial distress by applying survival analysis techniques to a sample of large US financial firms. We find that market indicators extracted from option prices significantly explain the survival time of troubled financial firms and do a better job in predicting financial distress than other time-varying covariates typically included in bank failure models. Overall, both accounting information and option prices contain useful information of subsequent financial problems and, more importantly, their combination produces good forecasts in a high-stress financial world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the United States, research projects conducted within the Federal Reserve System also focused on the potential use of information extracted from credit derivatives, such as Credit Default Swap (CDS) contracts (see e.g. Furlong and Williams 2006).

Covitz et al. (2004) propose an alternative explanation, which pertains to a supply-side effect in the debt market and the endogeneity of the decision to issue bank debt securities.

The appeal of considering option prices as bank risk metrics was also noted by Hamalainen et al. (2012), who examine the signaling qualities of various financial market indicators in the context of the Northern Rock crisis of September 2007. However, due to the small sample of UK banks used in their analysis, the research question is tackled in a graphical and descriptive manner.

In the present paper, we do not advocate in favor of an automatic conversion mechanism of contingent capital notes based solely on market indicators derived from option prices. Rather, in order to reduce the incidence of pricing errors in various bank securities markets, one could construct an idiosyncratic “composite” trigger based on equity prices, sub-debt/CDS spreads, and implied volatilities embedded in option prices. This idea is left for future work.

Note that most of the off-site surveillance literature is based on samples that are almost always dominated by small banks (see Reidhill and O’Keefe 1997; Gilbert et al. 1999, and references therein). However, one of the most important lessons from the recent financial crisis is that the largest financial institutions pose the greatest challenge from a financial stability perspective.

This is especially the case when the firm has a long history of paying a reasonable stable dividend rate. In our sample of large financial firms, dividend payments have been very common during the second part of the nineties.

It should be noted that government regulation may interfere with the bank dividend policy by persuading (or forcing) bank managers to cut dividends in order to improve solvability. For instance, in the US, the Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) framework under the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act (FDICIA) adopted in 1991 requires the suspension of dividend as a mandatory provision if the bank is found to be “undercapitalized.” Private discussions with US supervisors confirmed that for most (if not all) banking organizations the decision to cut dividends is made by the regulator and not by the bank’s board. Consequently, our empirical model may be viewed as one where the market is predicting when supervisors think the bank’s financial conditions have deteriorated sufficiently to require a dividend cut. Our inclusion of “non-bank” financial firms helps to address this concern. Moreover, we are not aware of any observable idiosyncratic measure of bank distress that does not depend in some important way on supervisory judgment.

The SEC’s Edgar Fillings are available at http://www.sec.gov/ or alternatively through the Reuters 3000 Xtra terminal; the BHC data is downloadable at http://www.chicagofed.org or may be accessed via Bankscope database (consolidation code C*). We extended our initial dataset only when the values of the financial ratios reported by various data providers were consistent. In addition, as a robustness check we rerun all the models containing IV as explanatory factor on a subsample of firms for which both the IV indicator and the financial ratios (composite score) are available (see infra).

In alternative specifications we also used the median and 75th percentile of the distribution of IV (score) in the overall sample to define the two subgroups (low IV/score vs. high IV/score). The survivor patterns are quite comparable to those depicted in Fig. 1b and c. For a more thorough discussion of the “optimal” value of the cut-off point used to discriminate between the two subgroups, see next section.

The Grambsch and Therneau (1994) tests of the proportional-hazards assumption assume homogeneity of variance across subgroups. This assumption may not hold in the special case of the stratified Cox regression. That’s why the proportional-hazards assumption is checked in this case separately for each stratum.

Alternatively, we also used the median and 75th percentile of the distribution of IV to define the IV dummy variable. The results are basically the same, both in terms of statistical significance and economic magnitude: the coefficient estimates of the IV dummy defined with respect to the median and top 25th quartile values are 2.411*** (p-value < .000) and 3.180*** (p-value < .000) respectively (output omitted).

In alternative specifications, we also included the financial ratios variables on an individual basis, but the Cox proportional hazard assumption was systematically rejected according to the results of the zero slope tests. Hence, to save space we decided not to report these additional results. Also, as a robustness check and for the sake of comparability across models, we rerun all the PH regressions reported in Table 5 on a subsample of firms for which both the IV indicator and the financial ratios (composite score) are available. The results, unreported for space reasons, are similar to those reported in Table 5. They are available upon request.

The piecewise correlation coefficients between quarterly averages of daily IV data and quarter-end composite score indicate a positive but imperfect correlation: +0.185*** (p-value < .000) in the overall sample; +0.349*** (p-value < .000) in the “banks” subsample; and +0.188*** (p-value < .000) in the “financial services firms” subsample. As pointed out by Bliss (2001), statistical theory indicates that combining various signals that are not perfectly correlated produce a more accurate assessment than either one alone.

Note that models 1 & 2 reported in Table 7 are not directly comparable with the other models reported in the same table because they are estimated on a different (larger) sample. For the sake of model comparability, we rerun models 1 & 2 on a “restricted” subsample of firms for which both the IV indicator and the financial ratios (composite score) are available. The coefficient estimates of IV continuous and IV dummy are −0.005*** (p-value < .000) and −0.539*** (p-value < .000) respectively (output omitted).

This is because in parametric models the origin of the analysis time determines when the risk of failure begins accumulating.

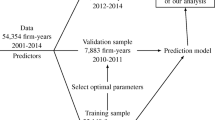

We refrain from conducting “out-of sample” analyses because this would imply to re-estimate our models over a somewhat tranquil period ending at the start of the subprime crisis and to compare the generated survival probability estimates with the observed outcomes during the 2007–2009 financial turmoil. As it is well known, during the current financial crisis banks and other FIs experienced huge amounts of losses and write-downs, far in excess of what most sophisticated risk, rating or pricing models would have predicted. Also, because of computational constraints, we report the “in-sample” predictive accuracy of the Cox PH models only.

In our case, the probability of “survival” refers to the event that a financial institution is not experiencing a dividend cut or suspension.

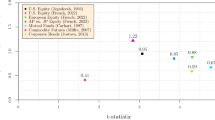

A similar test was performed by Gropp et al. (2006) in a somewhat different context.

We are grateful to an anonymous referee for suggesting the additional tests described in this section. The robustness results not included in the published version are available upon request from the authors.

The list of nine banks agreeing to receive preferred stock investments from the Treasury, published in the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) on October 14, 2008, includes: Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, J.P. Morgan Chase, Bank of America (including Merrill Lynch), Citigroup, Wells Fargo, Bank of New York Mellon, and State Street. The second list contains 19 large FIs: American Express, Bank of America, BB&T, Bank of New York Mellon, Capital One, Citigroup, Fifth Third, GMAC, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan Chase, Key Corp, MetLife, Morgan Stanley, PNC Financial, Regions, State Street, SunTrust, U.S. Bancorp, and Wells Fargo (see WSJ, May 8, 2009). The TBTF variables are naturally defined as dummy variables equal to 1 if the bank is on a “TBTF” list and 0 otherwise.

Seven (15) out of nine (19) FIs included in Paulson’s (Geithner’s) “TBTF” list cut their dividends at least once during the 2006—2009 period.

References

Andersen P, Borgan O, Gill R, Keiding N (1993) Statistical models based on counting processes. Springer, New York

Berger A (1991) Market discipline in banking. Proceedings of a Conference on Bank Structure and Competition. Fed Reserve Bank, Chicago, pp 419–437

Berger A, Davies S, Flannery M (2000) Comparing market and supervisory assessments of bank performance: who knows what when? J Money Credit Bank 32:641–667

Bessler W, Nohel T (1996) The stock market reaction to dividends cuts and omissions by commercial banks. J Bank Financ 20:1485–1508

Bessler W, Nohel T (2000) Asymmetric information, dividend reductions, and contagion effects in bank stock returns. J Bank Financ 24:1831–1848

Bliss R (2001) Market discipline and subordinated debt: a review of some salient issues. Fed Reserve Bank Chicago Econ Perspect QI:24–45

Bruni F, Paternò F (1995) Market discipline of banks’ riskiness: a study of selected issues. J Financ Serv Res 9:303–325

Burton S, Seale G (2005) A survey of current and potential uses of market data by the FDIC. FDIC Bank Rev 17:1–17

Calomiris C, Herring R (2012) Why and how to design a contingent convertible debt requirement. Brookings-Wharton Pap Finan Services, forthcoming

Cole R, Gunther J (1995) Separating the likelihood and timing of bank failure. J Bank Financ 19:1073–1089

Covitz D, Hancock D, Kwast M (2004) A reconsideration of the risk sensitivity of U.S. banking organization subordinated debt spreads: a sample selection approach. Fed Reserv Bank N Y Econ Policy Rev 10:73–92

Curry T, Elmer P, Fissel G (2004) Using market information to help identify distressed institutions: a regulatory perspective. FDIC Bank Rev 15:1–16

DeYoung R, Flannery M, Lang W, Sorescu S (2001) The information content of bank exam ratings and subordinated debt prices. J Money Credit Bank 33:900–925

Distinguin I, Rous P, Tarazi A (2006) Market discipline and the use of stock market data to predict bank financial distress. J Financ Serv Res 30:151–176

Evanoff D, Wall L (2000) Subordinated debt and bank capital reform. Working Paper No. 2000–07 Fed Reserve Bank Chicago

Evanoff D, Wall L (2001) Sub-debt yield spreads as bank risk measures. J Financ Serv Res 20:121–145

Evanoff D, Wall L (2002) Measures of the riskiness of banking organizations: subordinated debt yields, risk-based capital, and examination ratings. J Bank Financ 26:989–1009

Flannery M (1998) Using market information in prudential bank supervision: a review of the U.S. empirical evidence. J Money Credit Bank 30:273–305

Flannery M (2001) The faces of “market discipline”. J Financ Serv Res 20:107–119

Flannery M (2005) No pain, no gain? Effecting market discipline via reverse convertible debentures. In: Scott HS (ed) Capital adequacy beyond Basel: banking, securities, and insurance. Oxford University Press, pp 171–196

Flannery M (2009a) Market-valued triggers will work for contingent capital instruments. Solicited submission to U.S. Treasury Working Group on Bank Capital, University of Florida, November

Flannery M (2009b) Stabilizing large financial institutions with contingent capital certificates. Working Paper No. 4, CAREFIN

Flannery M, Sorescu S (1996) Evidence of bank market discipline in subordinated debentures yields: 1983–1991. J Finance 51:1347–1377

Furlong F, Williams R (2006) Financial market signals and banking supervision: are current practice consistent with research findings? Fed Reserve Bank San Francisco Econ Rev: 17–29

Gilbert A, Meyer A, Vaughan M (1999) The role of supervisory screens and econometric models in off-site surveillance. Fed Reserve Bank St. Louis Rev 81:31–56

Grambsch P, Therneau T (1994) Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 81:515–526

Gropp R, Vesala J, Vulpes G (2006) Equity and bond market signals as leading indicators of bank fragility. J Money Credit Bank 38:399–428

Hamalainen P, Pop A, Hall M, Howcroft B (2012) Did the market signal impending problems at Northern Rock? An analysis of four financial instruments. Eur Financ Manag 18:68–87

Hancock D, Kwast M (2001) Using subordinated debt to monitor Bank Holding Companies: is it feasible? J Financ Serv Res 20:147–187

Jagtiani J, Lemieux C (2001) Market discipline prior to bank failure. J Econ Bus 53:313–324

Kalbfleisch J, Prentice L (1980) The statistical analysis of failure time data. John Wiley & Sons, New York

Krainer J, Lopez J (2008) Using securities market information for bank supervisory monitoring. Int J Cent Bank 4:125–164

Lin D, Wei L (1989) The robust inference for the Cox Proportional Hazard model. J Am Stat Assoc 84:1074–1078

Morgan D, Stiroh K (2001) Market discipline of banks: the asset test. J Financ Serv Res 20:195–208

Peto R, Peto J (1972) Asymptotically efficient rank invariant procedures. J R Stat Soc 135:185–207

Prentice R (1978) Linear rank tests with right censored data. Biometrika 65:167–179

Reidhill J, O’Keefe J (1997) Off-site surveillance systems. In: History of the eighties: lessons for the future. FDIC, Washington, DC, pp 477–520

Schmidt J (2004) A review of the use of market data in the Federal Reserve System. Conference Paper, Fed Reserve Bank Cleveland. http://www.clevelandfed.org/research/conferences/2004/march/schmidt.pdf. Accessed 11 Sept 2012

Sironi A (2001) An analysis of European banks’ SND issues and its implications for the design of a mandatory subordinated debt policy. J Financ Serv Res 20:233–266

Slovin M, Sushka M, Polonchek J (1999) An analysis of contagion and competitive effects at commercial banks. J Financ Econ 54:197–225

Squam Lake Working Group on Financial Regulation (2009) An expedited resolution mechanism for distressed financial firms: regulatory hybrid securities. Policy Paper No. 3, Squam Lake Working Group

Swidler S, Wilcox J (2002) Information about bank risk in options prices. J Bank Financ 26:1033–1057

Wall L (2010) Prudential discipline for financial firms: micro, macro, and market structures. Working Paper No. 2010–9, Fed Reserve Bank Atlanta

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Rob Bliss, Jean-Bernard Chatelain, Gilbert Colletaz, Henri Pagès, Jean-Paul Pollin, Christian Rauch, Catherine Refait-Alexandre, Haluk Ünal (the Editor), Larry Wall, an anonymous referee and participants at the 14th Annual European Conference of the Financial Management Association (FMA), 42th Annual Conference of the Money, Macro, and Finance (MMF) Research Group, Banque de France Research Foundation Seminar, 58th Annual Meetings of the French Economics Association (AFSE), 27th International Symposium on Banking and Monetary Economics and seminar participants at the Banque de France, University of Nantes (LEMNA) and University of Orleans (LEO) for their useful comments. The views expressed in this article are exclusively those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the institutions they belong to, especially the Banque de France or the French Prudential Supervision Authority. All remaining errors are our own responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coffinet, J., Pop, A. & Tiesset, M. Monitoring Financial Distress in a High-Stress Financial World: The Role of Option Prices as Bank Risk Metrics. J Financ Serv Res 44, 229–257 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-012-0150-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-012-0150-2

Keywords

- Bank market discipline

- Financial system oversight

- Financial distress

- Options

- Implied volatility

- Survival analysis