Abstract

The IPCC reports that climate change will pose increased risks of heatwaves and flooding. Although survey-based studies have examined links between public perceptions of hot weather and climate change beliefs, relatively little is known about people’s perceptions of changes in flood risks, the extent to which climate change is perceived to contribute to changes in flood risks, or how such perceptions vary by political affiliation. We discuss findings from a survey of long-time residents of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA, a region that has experienced regular flooding. Our participants perceived local flood risks as having increased and expected further increase in the future; expected higher future flood risks if they believed more in the contribution of climate change; interpreted projections of future increases in flooding as evidence for climate change; and perceived similar increases in flood risks independent of their political affiliation despite disagreeing about climate change. Overall, these findings suggest that communications about climate change adaptation will be more effective if they focus more on protection against local flood risks, especially when targeting audiences of potential climate sceptics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A total of 23 of these 200 (11.5 %) had missing values on at least one of the questions analyzed here. Missing values therefore differ across analyses. The 23 incomplete responders showed no significant differences from the 177 complete responders in terms of demographic characteristics, flood experience, or political affiliation (p > .05).

We computed average population age from the age categories reported in the 2000 Pittsburgh Census data (downloaded from http://www.city-data.com/us-cities/The-Northeast/Pittsburgh-Population-Profile.html). Specifically, we multiplied the proportion of individuals in each age category by the mid-point of that age category and then computed the overall sum.

One of our nine focal measures (i.e., those listed in Table 1) showed a marginal difference, suggesting that participants with a college education were marginally less likely to interpret the stable flood trend prediction as resulting from climate change (M = 3.33, SD = 1.77 vs. M = 3.86, SD = 1.97), t(191) = 1.98, p = .05.

Floods were defined as involving “water covering some normally useful dry land, where there are several houses or other buildings; water that is more than one foot deep; and water that stays around for a day or more.” Extreme floods were defined as “water covering some useful normally dry land, where there are several houses or other buildings; water that is more than 1 foot deep; and water that stays around days or even weeks.” We followed with a description of the Western Pennsylvania Flood of 2004, which, in pilot interviews, appeared to be well remembered by Pittsburgh residents: “On September 9, 2004, at the tail end of hurricane season, the Pittsburgh region had record-breaking rainfall of 3.6 inches with 5.95 inches falling 9 days later. On September 19, 2004, the rivers crested at 31 feet, 6 feet over flood levels. Extreme flooding and mud slides damaged or destroyed numerous bridges and closed hundreds of roads. Thousands of homes and businesses in Allegheny County and the surrounding counties of Armstrong, Beaver, Butler, Indiana, Washington, and Westmoreland were severely damaged or destroyed by this extreme flooding.”

We started by asking about the present, because it is a natural reference point against which to compare changes from the past and into the future. People are willing and able to report probabilities for future events (Bruine de Bruin et al. 2007; Hurd and McGarry 2002). People are also willing and able to report perceived probabilities for past events, although in hindsight they may be overconfident about how much they knew about the likelihood of events happening (Fischhoff 1975). Yet, our sample showed no significant correlation of older age with reported flood risks for 1963 (r = .05, p > .05 for typical floods; r = .00, p > .05 for extreme floods). Nor were perceived changes in flood risk from 1963 to 2013 correlated with age (r = −.04, p > .05 for typical floods; r = −.03, p > .05 for extreme floods).

We also asked participants direct questions about perceived changes in flood risks, in terms of whether typical and extreme floods would be ‘more likely,’ ‘less likely,’ or ‘about as likely’ in the year 2063 as compared to 2013, and in the year 1963 as compared to 2013. We found significant Spearman rank correlations between these direct responses and the differences between reported flood risks (ranging from .31 to .44, all p<.001).

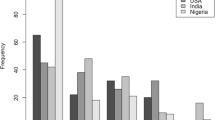

Because the three graphs were initially presented together, we did not counterbalance the order in which graphs were subsequently presented again. Our goal was to examine the perceived role of climate change in the presented flood projections, and not to test whether people could accurately identify the presented trends. Yet, we did assess participants’ ability to recognize the trends in the presented flood trend predications and found that the graph of the stable flood trend (Fig. 1a) was correctly identified by 67.2 % as stable, graph of the increasing flood trend prediction (Fig. 1b) was correctly identified by 89.0 % as increasing, the graph of the decreasing flood trend (Fig. 1c) was correctly identified by 82.5 % as decreasing. Limiting analyses to those participants who correctly perceived all three trends had no effect on the reported findings regarding the perceived role of climate change.

As might be expected, the specific role of climate change differed by the type of flood trend prediction. A separate ANOVA on agreement with the statements of specific consequences of climate change (more vs. less rain) by flood trend predictions (increasing vs. stable vs. decreasing), F(1, 182) = 77.02, p < .001 found that the perceived contribution of more rain due to climate change was highest for the increasing flood trend prediction, showing a linear decline over the three type of flood trend predictions (M = 5.08, SD = 1.70 vs. M = 3.65, SD = 1.87 vs. M = 2.74, SD = 1.68) with the opposite linearly decreasing pattern being found for the perceived contribution of less rain due to climate change (M = 2.39, SD = 1.57 vs. M = 3.05, SD = 1.72 vs. M = 4.35, SD = 1.85). Again, Democrats showed systematically stronger climate change beliefs than did non-Democrats across these questions, F(1, 182) = 9.63, p < .01, with no additional main effects or interactions for flood experience (yes vs. no) or type of climate change beliefs (more vs. less rain).

References

Bostrom A, Morgan MG, Fischhoff B et al (1994) What do people know about global climate-change. 1. Mental models. Risk Anal 14:959–970

Boykoff MT (2008) Lost in translation? United States television news coverage of anthropogenic climate change, 1995-2004. Climatic Change 86:1–11

Bradford RA, O’Sullivan JJ, van der Craats IM et al (2012) Risk perception—issues for flood management in europe. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 12:2299–2309

Brody SD, Zahran S, Vedlitz A, Grover H (2008) Examining the relationship between physical vulnerability and public perceptions of global climate change in the United States. Enviorn Behav 40:72–95

Burningham K, Fielding J, Thrush D (2007) ‘It’ll never happen to me’: understanding public awareness of local flood risk. Disasters 32:216–238

Bruine de Bruin W, Bostrom A (2013) Assessing what to address in science communication. PNAS 110:14062–14068

Bruine de Bruin W, Parker AM, Fischhoff B (2007) Can adolescents predict significant life events? J Adolesc Health 41:208–210

Corbett JB, Durfee JL (2004) Testing public (un)certainty of science: media representations of global warming. Sci Commun 26:129–151

Deryugina T (2013) How do people update? The effects of local weather fluctuations on beliefs about global warming. Clim Change 118:397–416

Donner SD, McDaniels J (2013) The influence of national temperature fluctuations on opinions about climate change in the US since 1990. Clim Change 118:537–550

Egan PJ, Mullin M (2012) Turning personal experience into political attitudes: the effect of local weather on Americans’ perceptions about global warming. J Polit 74:796–809

Fischhoff B (1975) Hindsight ≠ Foresight. The effect of outcome knowledge on judgment under uncertainty. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 1:288–299

Guber DL (2013) A cooling climate for climate change? Party polarization and the politics of global warming. Am Behav Sci 57:93–115

Hamilton LC, Stampone MD (2013) Blowin’ in the wind: short-term weather and belief in anthropogenic climate change. Weather Clim Soc 5:112–119

Hurd MD (2009) Subjective probabilities in household surveys. Annu Rev Eco 1:1–23

Hurd MD, McGarry K (2002) The predictive validity of subjective probabilities of survival. Econ J 112:966–985

Keller CM, Siegrist M, Gutscher H (2006) The role of the affect and availability heuristics in risk communication. Risk Anal 26:631–639

Krosnick JA, Holbrook AL, Lowe L et al (2006) The origins and consequences of democratic citizens’ policy agendas: a study of popular concern about global warming. Clim Change 77:7–43

Kunkel KE et al (2013) Monitoring and understanding trends in extreme storms: state of knowledge. Bull Am Meteorolo Soc 94(4):499–514

Li Y, Johnson EJ, Zaval L (2011) Local warming: daily temperature change influences belief in global warming. Psychol Sci 22:454–459

Locke EA, Latham GP (1990) A theory of goal setting and task performance. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Marx SM, Weber EU, Orlove BS, Leiserowitz A, Krantz DH, Roncoli C, Phillips J (2007) Communication and mental processes: experiential and analytic processing of uncertain climate information. Glob Environ Change 17:47–58

Morgan MG, Fischhoff B, Bostrom A, Atman CJ (2002) Risk communication: a mental models approach. Cambridge University Press, New York

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Weather Service (2014). http://water.weather.gov/ahps2/crests.php?wfo=pbz&gage=pttp1

O’Connor RE, Yarnal B, Dow K, Jocoy CL, Garbone CJ (2005) Feeling at risk matters: water managers and the decision to use forecasts. Risk Anal 25:1265–1273

Pennsylvania Department of State. Current voter registration statistics. Downloaded on 24 July 2014. http://www.alleghenycounty.us/elect/201204pri/el45.htm

Peterson TC, Stott PA, Herring S (2012) Explaining extreme events of 2011 from a climate perspective. Bull Am Meteorolo Soc 93:1041–1067

Pittsburgh Post Gazette (2004) The flood and more of 2004. Downloaded on 26 July 2014. http://www.post-gazette.com/local/north/2004/12/29/The-flood-and-more-of-2004/stories/200412290273

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2008) Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 40:879–891

Ratter BMW, Philipp KHI, von Storch H (2012) Between hype and decline: recent trends in public perception of climate change. Environ Sci Policy 18:3–8

Read D, Bostrom A, Morgan MG et al (1994) What do people know about global climate-change. 2. Survey studies of educated laypeople. Risk Anal 14:971–982

Reynolds TW, Bostrom A, Read D et al (2010) Now what do people know about global climate change? Survey studies of educated laypeople. Risk Anal 30:1520–1538

Siegrist M, Gutscher H (2008) Natural hazards and motivation for mitigation behavior: people cannot predict the affect evoked by severe flood. Risk Anal 28:771–778

Spence A, Poortinga W, Butler C, Pidgeon NF (2011) Perceptions of climate change and willingness to save energy related to flood experience. Nat Clim Change 1:46–49

Spence A, Poortinga W, Pidgeon NF (2012) The psychological distance of climate change. Risk Anal 32:957–972

Stocker T, Dahe Q, Plattnter GK (2013) Working group I contribution to the IPCC fifth assessment report (Ar5), climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Geneva

Taylor AL, Bruine de Bruin W, Dessai S (2014) Climate change beliefs and perceptions of weather-related changes in the United Kingdom. Risk Anal. doi:10.1111/risa.12234

U.S. Census Bureau (2014) State and County QuickFacts. Downloaded on 24 July 2014. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/42/4261000.html

Weber EU, Stern PC (2011) Public understanding of climate change in the United States. Am Psychol 66:315–328

Weinstein ND, Diefenbach MA (1997) Percentage and verbal category measures of risk likelihood. Health Edu Res 1997(12):139–141

Whitmarsh L (2008) Are flood victims more concerned about climate change than other people? The role of direct experience in risk perception and behavioural response. J Risk Res 11:351–374

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the center for Climate and Energy Decision Making (SES-0949710), through a cooperative agreement between the National Science Foundation and Carnegie Mellon University. We thank Carmen Lefevre, Kelly Klima, and Andrea Taylor for their comments and insights.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bruine de Bruin, W., Wong-Parodi, G. & Morgan, M.G. Public perceptions of local flood risk and the role of climate change. Environ Syst Decis 34, 591–599 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-014-9513-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-014-9513-6