Abstract

Background

Self-reported adherence to direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) to treat hepatitis C virus (HCV) among persons who inject drugs (PWID) is often an overreport of objectively measured adherence. The association of such overreporting with sustained virologic response (SVR) is understudied. This study among PWID aimed to determine a threshold of overreporting adherence that optimally predicts lower SVR rates, and to explore correlates of the optimal overreporting threshold.

Methods

This study analyzed per-protocol data of participants with adherence data (N = 493) from the HERO (Hepatitis C Real Options) study. Self-reported and objective adherence to a 12-week DAA regimen were measured using visual analogue scales and electronic blister packs, respectively. The difference (Δ) between self-reported and objectively measured adherence was calculated. We used the Youden index based on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to identify an optimal threshold of overreporting for predicting lower SVR rates. Factors associated with the optimal threshold of overreporting were identified by comparing baseline characteristics between participants at/above versus those below the threshold.

Results

The self-reported, objective, and Δ adherence averages were 95.1% (SD = 8.9), 75.9% (SD = 16.3), and 19.2% (SD = 15.2), respectively. The ≥ 25% overreporting threshold was determined to be optimal. The SVR rate was lower for ≥ 25% vs. < 25% overreporting (86.7% vs. 95.8%, p <.001). The factors associated with ≥ 25% Δ adherence were unemployment; higher number of days and times/day of injecting drugs; higher proportion of positive urine drug screening for amphetamine, methamphetamine, and oxycodone, and negative urine screening for THC (tetrahydrocannabinol)/cannabis.

Conclusions

Self-reported DAA adherence was significantly greater than objectively measured adherence among PWID by 19.2%. Having ≥ 25% overreported adherence was associated with optimal prediction of lower SVR rates. PWID with risk factors for high overreporting may need to be more intensively managed to promote actual adherence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Persons who inject drugs (PWID) are at a high-risk for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection [1]. As per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2020 surveillance report, the majority of HCV infections in the United States are the consequence of sharing drug injection equipment [2]. The prevalence of HCV antibodies has been estimated at 52.3% among PWID globally [3]. While direct-acting antiviral (DAA) medications for HCV have been found to be highly effective irrespective of current/former substance use status, lower treatment completion rates may affect the cure rates among PWID [4, 5]. Evidence suggests that higher adherence increases the chances of HCV cure among PWID [5], and having at least 50% objectively measured adherence substantially increases the chances of HCV cure among PWID, with a likelihood of achieving cure increasing further for every 5% interval above the 50% objective adherence threshold [6]. Therefore, it is critical to provide PWID with the support needed to ensure optimal adherence [7].

Self-reported adherence measures, such as the visual analog scale (VAS), are easier to implement in clinical settings than objective measures [8]. Previous studies using objective adherence measures such as pill counts among veterans [9] and electronic blister packs among PWID (including active drug users) [10] provide evidence for the validity of the VAS for measuring DAA adherence by showing that self-reported adherence measured using the VAS is associated with objectively measured adherence. However, self-reported measures of adherence have been found to overestimate the actual level of adherence both in the general population [8] and among PWID with recent drug use [11]. The extent of overestimation is an unknown that reduces the utility of the self-report measure. If the level of overreporting of adherence could be estimated and the associated factors identified, PWID receiving DAAs could be supported to attain at least the minimum levels of adherence that optimize the chances of cure.

Prior studies have investigated factors associated with overreporting adherence in other contexts such as antihypertensives [12] and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis [13, 14], and suggested that factors such as socioeconomic status and health beliefs [12], educational level [13], race [14], and age [13, 14] may predict overreporting of adherence. Exploring factors associated with overreporting could help clinicians look for signs for overreporting adherence and target those individuals for appropriate support to improve adherence and the treatment outcomes. To our knowledge, no studies have explored factors associated with overreporting adherence to DAAs among PWID or other populations living with HCV. Furthermore, the extent to which overreporting is associated with poorer chances of cure or sustained virologic response (SVR) rates has not been examined.

The HERO (Hepatitis C Real Options) study [5] measured adherence through both self-report using VAS and objectively using electronic blister packs. Analyzing these data, the present study aimed to: (1) investigate the extent of discrepancy between self-reported and objective measurements of adherence; (2) determine a threshold of overreporting for optimally predicting a lower SVR rate; and (3) explore the factors associated with the optimal threshold of overreporting.

Methods

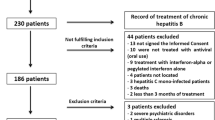

Study design and sample

This study included a secondary analysis of data from the HERO study (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02824640) [5, 15]. The HERO study was a pragmatic randomized clinical trial conducted across eight opioid treatment programs (OTPs) and fifteen community health centers (CHCs) in eight US states among DAA-naïve PWID with active drug injection use within 90 days of screening. Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to two modes of administration: modified Directly Observed Therapy (mDOT) and Patient Navigation (PN). All participants received a 12-week course of sofosbuvir 400 mg and velpatasvir 100 mg fixed-dose combination therapy in electronic blister packs. Participants were given a maximum compensation of $400 ($20 for completing each of 17 research visits, and $5 for returning the electronic blister packs for each of 12 weeks of treatment). Outcomes included and compared the rates of HCV cure, as well as HCV DAA treatment initiation, completion, and adherence between the two study arms.

The analytic sample for this study is based on the per-protocol sample in the HERO study (N = 501), defined as those participants who received the treatment condition as assigned to them through the HERO study randomization procedure and had a determined SVR status after the end of treatment [5] and included those who had at least one data point on adherence to DAAs, in the form of both self-report and objective measurement (N = 493).

Measures

Participant characteristics

Self-report survey questionnaires were used to collect information on demographic and clinical characteristics and injection drug use. Additionally, data on urine toxicology results for substance use at baseline were extracted from medical chart review. For analysis in this study, we included all available demographic measures: age, race, ethnicity, gender, relationship status, education, housing stability, and employment status. Clinical characteristics included were depression, measured using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [16]; anxiety, measured using the 7-item generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7) [17]; and HIV coinfection. Depression has been associated with poorer adherence [18]. Anxiety is correlated with depression, is the most common mental health issue diagnosis along with depression in the HCV-infected population [19, 20], and was associated with poorer adherence in the interferon-era [21]. HIV coinfection may affect adherence due to the pill burden [22]. All substance use behavior measures at baseline were analyzed because substance use behaviors were associated with objective adherence in the parent study [5]. The substance use behavioral assessments included self-reported injection drug use in the past three months (cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, crack, fentanyl, and polysubstance) and urine drug test positivity (amphetamine, methamphetamine, benzodiazepine, cocaine, THC [tetrahydrocannabinol]/cannabis, opiate, and oxycodone) at baseline.

Self-reported DAA adherence

Adherence to the DAA regimen was self-reported at weeks 4, 8, and 12 during the treatment period using a single item VAS instrument: “How much of your pills have you taken in the past 30 days?” The response was a continuous value between 0 and 100%. Overall self-reported adherence was calculated by taking an average of all available data on self-reported adherence. To enable stratified analyses, we created six categorical levels of overall self-reported adherence: <80%, 80–85%, > 85–<90%, 90–95%, > 95–<100%, and 100%.

Objective DAA adherence

Adherence was also objectively measured using electronic blister packs that recorded the day and time of medication removal. Our prior studies explored changes in weekly objective adherence over time and found that objectively measured weekly adherence declined over the 12-week treatment period for both arms [5, 23]. In this study, however, we focused on overall objective adherence as it is more relevant for the outcome of SVR than the consistency of week-by-week adherence. Overall objective adherence was calculated by averaging the weekly objective adherence rate for the 12 weeks of treatment.

Difference between self-reported and objective adherence

The difference between self-reported and objective adherence was operationalized in the following two ways:

-

Delta (Δ) adherence: This variable was a continuous variable calculated as the difference between overall self-reported and overall objective adherence. Positive nonzero values of Δ adherence indicated overreporting, negative values indicated underreporting, and value = 0 indicated correct reporting of HCV DAA adherence.

-

Overreporting thresholds: This included six binary variables indicating different overreported adherence thresholds. Six different cutoffs of Δ adherence (≥ 5%, ≥ 10%, ≥ 15%, ≥ 20%, ≥ 25%, and ≥ 30%) were used to create these binary variables.

SVR

SVR, defined as having HCV RNA (ribonucleic acid) level below the limit of quantitation (≤ 15 IU/mL), equivalent to cure, was ascertained at least 12 weeks after treatment completion. HCV RNA was tested by Quest Diagnostics using COBAS TaqMan real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). The window period for SVR determination was set to between 70 and 365 days following HCV treatment completion. SVR was treated as a binary variable in our analyses (no HCV cure = 0 and HCV cure = 1).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were conducted using the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. The association of continuous self-reported adherence with objective adherence was tested using linear regression. Scatter plots were created to enable visual inspection of the relationship of self-reported adherence with objective adherence and Δ adherence. Δ Adherence was compared between the six categorical levels of self-reported adherence using generalized linear model regression. SVR rates were compared by each of the binary overreporting thresholds, e.g., ≥ 5% vs. < 5%, ≥ 10% vs. < 10%, and so on. To identify an overreporting threshold that is optimally associated with predicting lower SVR, we used the Youden index (= sensitivity + specificity-1) based on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis [24]. Using the optimal overreporting threshold determined through the ROC curve analyses, we compared persons falling at/above the threshold vs. those below the threshold with respect to SVR rates, and the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics. For two-sample comparisons, chi-square/Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables, and independent samples t tests/Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used for continuous variables. All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of the study sample

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample at baseline are presented in Table 1. The mean (M) age in the study sample was 44.1 [standard deviation (SD) = 11.5] years. The study sample was 72.4% male, 63.6% White, and 22.9% Hispanic. A majority of the sample (87.4%) reported their relationship status as single, separated, divorced, or widowed. The highest level of education completed was high school or less for 61.8% of the sample, 64.8% were unemployed, 57.6% did not have their own transportation, and 48.0% were living in unstable housing conditions.

Association between Self-reported and objective adherence

The results of our analyses suggested a significant positive association between self-reported and objective adherence. For every 1% increase in self-reported adherence, the objective adherence was higher by an estimated average of 0.7% [95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.6%, 0.9%; p <.001]. The OTP and CHC groups were not significantly different in the average overall self-report [M (SD) = 96% (8%) for OTP vs. 95% (10%) for CHC, p =.180) overall objective adherence [M (SD) = 77% (16%) for OTP vs. 75% (16%) for CHC, p =.097). In the non-per-protocol sample who initiated treatment, 85 participants had at least one data point available on both self-report and objective measures of adherence. Compared to our study sample, the 85 non-per-protocol participants who initiated treatment had significantly lower overall objective adherence [M (SD) = 67% (20%) vs. 76% (16%), p <.001), but not significantly different overall self-report adherence [M (SD) = 94% (14%) vs. 95% (9%) in our study sample, p =.553].

Difference between self-report and objective adherence

The scatter plot depicting actual observed values for objective vs. self-reported adherence in Fig. 1 shows that self-reported adherence was overreported by most persons in our study sample compared to their objective adherence values. Table 2 presents the descriptive results for the adherence measures in the total sample and stratified by six categorical levels of self-reported adherence. In the total study sample, the average self-reported adherence was higher in comparison to the average objective adherence [M (SD) = 95.1% (8.9%) vs. 76.0% (16.3%)], and the results were similar within each categorical level of self-reported adherence. The < 80% self-reported adherence category had the smallest average Δ adherence [M (SD) = 5.0% (22.0)]. Compared to the < 80% self-reported adherence category, the average Δ adherence was significantly greater for all of the other self-reported adherence categorical levels.

The markers represent observed values for each of the sample participants. The green and red markers denote participants who did and did not achieve SVR, respectively. The diagonal is the line of equality.

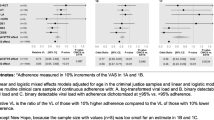

Relation of varying overreporting thresholds with SVR

The results of analyses comparing SVR rates by binary overreporting levels are presented in Table 3. SVR rates were significantly lower for overreporting at ≥ 15% vs. < 15%, ≥ 20% vs. < 20%, ≥ 25% vs. < 25%, and ≥ 30% vs. < 30%. The difference of 9.1% in the SVR rates between the ≥ 25% and < 25% overreporting levels was highly significant (p <.001).

The overreported adherence thresholds for optimally predicting lower SVR rate

Based on the ROC curve analysis, the threshold of ≥ 26.2 Δ adherence had the largest Youden index value of 0.3 for predicting the outcome of SVR. Rounding to the nearest five, a threshold of ≥ 25% Δ adherence was selected as the optimal overreporting threshold to indicate a problematic level of overreporting adherence. In our study sample, 32.1% of the participants had ≥ 25% overreported adherence.

Table 4 shows the differences in SVR rates between ≥ 25% and < 25% overreported adherence groups for the total study sample and stratified by six categorical levels of self-reported adherence. Within the 90‒<95% and 100% self-reported adherence categories, the SVR rate was significantly lower for ≥ 25% vs. < 25% overreported adherence. Figure 2 shows that a majority of those without SVR are positioned above the 25% Δ adherence threshold line whereas a majority of those with SVR are below the 25% Δ adherence threshold line.

The markers represent observed values for each of the sample participants. The green and red markers denote participants who did and did not achieve SVR, respectively. The 5% and 25% Δ adherence thresholds are shown as red horizontal lines.

Factors associated with the optimal overreporting threshold (≥ 25%)

A comparison of characteristics by ≥ 25% vs. < 25% overreporting groups is presented in Table 1. Employment status was the only sociodemographic variable associated with ≥ 25% overreporting wherein persons with ≥ 25% overreporting had higher rates of unemployment compared to those below the 25% overreporting level (72.0% vs. 61.4%, p =.02).

Various drug-related variables were associated with ≥ 25% overreporting, including the number of days of injecting drugs in the previous 3-months, the number of times per day of injecting drugs, and positive urine test results for drug use. More specifically, the ≥ 25% Δ adherence had a higher average number of days of injecting drugs in the 3-month period before baseline (41.1 vs. 28.0, p <.001), a higher average number of times per day of injecting drugs (3.2 vs. 2.7, p =.001), a larger proportion of positive urine test results for amphetamine (37.1% vs. 23.4%, p =.002), methamphetamine (39.7% vs. 27.4%, p =.007), and oxycodone (34.4% vs. 23.4%, p =.011), but a smaller proportion of positive urine test results for THC (tetrahydrocannabinol)/cannabis (43.0 vs. 53.3, p =.038) compared to those with < 25% Δ adherence.

Discussion

Although self-reported adherence using the VAS measure was significantly associated with objective adherence measured using electronic blister packs, it overestimated adherence by 19.2% on average. The ≥ 25% overreporting was determined as the optimal threshold for predicting SVR and was associated with lower rates of SVR vs. the < 25% Δ adherence group (86.7% vs. 95.8%). Unemployment, higher rates of substance use behaviors, positive urine drug test results for amphetamine, methamphetamine, and oxycodone, and negative urine drug test results for THC/cannabis predicted having ≥ 25% overreporting of adherence.

There is considerable evidence indicating that self-reported measures for HCV DAA adherence tend to overestimate actual adherence [25]. The findings of our study are consistent with some prior studies that measured objective adherence with electronic blister packs among PWID [10, 26] and studies that measured objective adherence using medication event monitoring system (MEMS) caps and pill counts among the general population treated for chronic HCV [27] where self-reported adherence overestimated actual adherence. Our estimate of 19.2% difference between the self-reported and the objective measures is comparable to the difference of approximately 17% estimated in a prior study [10]. However, another study among veterans did not find any significant differences between self-reported and objective (pill counts) measurements, wherein the mean objective adherence at 4-, 8-, and 12-week timepoints was 96.2%, 95.2%, and 98.2%, respectively, while the mean VAS adherence was 96.2%, 96.0%, and 98.2, respectively, at each of the timepoints [9]. This inconsistency between our study and the prior study by Burton et al. (2018) could be attributed to differences in the type of populations studied and to incorporation of an interviewer-assisted method for collecting self-reported data in the prior study. The accuracy of the self-reported data can be enhanced (i.e., the extent of overreporting can be reduced) through various measures such as including interviewer assistance [9], facilitating recall through use of optimal recall periods [28], measuring proportion rather than counts of medications taken, and reducing social desirability bias by letting respondent know that nonadherence is normal or avoiding face-to-face data collection [8]. However, our results may be applied only in contexts where such measures for enhancing self-reporting of adherence are not available or feasible. The comparability of our results to other studies may also be affected by the type of objective adherence measure used. A study reviewing different technology-based HCV DAA adherence measures found that the adherence ranges in studies using pill counts (> 98%) were higher compared to those using technology-based measures such as MEMS caps and ingestible sensors (95–97%), weekly adherence through electronic blister packs (73–98%), and electronic pill boxes (39–89%) [25].

Our study also examined how high overreporting of adherence relates to the treatment-related outcome of SVR. Overreporting adherence by ≥ 25% was determined as the optimal threshold for maximally predicting a lower SVR rate and was associated with ~ 9% lower SVR rate than those with < 25% overreported adherence. Within the self-reported adherence categories, the difference in SVR rates between < 25% vs. ≥ 25% overreporting was significant (p value < 0.05) or marginally significant (p value between 0.05 and 0.1) only for the higher ordered categories of self-reported adherence. An implication of this finding is that while those overreporting adherence at lower levels of self-reported adherence may still be recognized as having less than optimal adherence and receive support for improving adherence, low actual adherence may go unrecognized among those self-reporting high adherence, and they would likely be missed by interventions to support adherence.

Prior studies in the HIV prevention context found that age, educational level [13], and race [14] predicted overreporting of medication adherence. Our study found that characteristics such as unemployment and drug use characteristics were predictive of having overreporting ≥ 25%. Unemployment, a social determinant of health [29], is a personal resource barrier that reduces access to care and consequently affects HCV treatment compliance [30]. Substance use before or during treatment may interfere with HCV DAA adherence [11, 26]. Although clinical practices may not be able to identify overreporting patients at the individual level, knowledge about the factors/characteristics associated with overreporting may help identify patient populations at risk of high overreporting and support them for improving their actual adherence. Providing appropriate adherence supports that address the complex needs of the substance use population can help bridge the gap in adherence levels and SVR rates between people who use drugs and people who do not use drugs [31,32,33]. An example of an adherence support is the Toronto Community Hep C Program (TCHCP) which works collaboratively with community social support service agencies and features integration of a variety of services including primary care, infectious disease specialist, mental health, peer support, psycho-educational support groups, harm reduction program, case management, healthy meals, and travel support [32, 34]. In our study THC/cannabis use was associated with a protective effect against having ≥ 25% overreporting of adherence. There is evidence from the interferon era suggesting that cannabis use may facilitate HCV treatment adherence [35], an effect attributed to THC/cannabis ameliorating the severe adverse effects of interferon such as nausea [36]. These results support the existing advocacy for removal of cannabis use as a barrier for persons undergoing HCV treatment [36].

An added contribution of our study is examining the discrepancy between self-reported and objective adherence by varying levels of self-reported adherence. All the categories of self-reported adherence falling in the 80‒100% range had a substantially greater discrepancy between self-reported and objective adherence than the < 80% self-reported adherence category. No other studies have examined how overreporting varies based on the level of self-report. Because objective adherence measures are typically not available in clinical settings, the importance of our study is that our findings may help clinicians estimate patients’ actual level of adherence based on the self-reported adherence measure and provide additional support to help them succeed in maintaining adequate levels of adherence. Our results may also be used to gauge the level of bias introduced in treatment studies among PWID that rely on incorporating the exclusive use of the self-reported adherence measure.

Our study has some limitations. The study sample had relatively lower proportions of women, persons from minority racial/ethnic groups and persons from rural areas. The sample sizes for some categorical levels of self-reported adherence were small. Our study has several strengths. This is one of the first studies to focus on investigating how varying levels of discrepancy between self-reported and objective adherence measures relates to SVR. While overreporting adherence is common, we have determined a threshold of overreporting that is predictive of significantly worse chances of achieving SVR; the validity of this threshold for predicting SVR should be tested further in future studies. By exploring the correlates of problematic levels of overreported adherence with respect to achieving the SVR outcome, our study also helps define the subpopulation of PWID with HCV who may benefit from additional adherence support.

Conclusions

Overreporting of adherence to HCV DAAs was greater at higher levels of self-reported adherence among PWID. Having ≥ 25% overreported adherence was associated with poorer chances of achieving HCV cure. Providers may need to intensively support PWID with risk factors for high overreporting to promote adherence and maximize the probability of SVR, possibly by addressing pressing needs such as finding employment and actively linking patients to substance use treatment.

Data availability

The dataset used for the current study is not publicly available because it contains information that could compromise the privacy of the research participants. The dataset is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- DAA:

-

Direct-Acting Antiviral

- GAD:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C Virus

- HERO:

-

Hepatitis C Real Option

- M:

-

Mean

- mDOT:

-

Modified Directly Observed Therapy

- MEMS:

-

Medication Event Monitoring System

- PHQ:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- PN:

-

Patient Navigation

- PWID:

-

Persons who Inject Drugs

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic Acid

- ROC:

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SVR:

-

Sustained Virologic Response

- THC:

-

Tetrahydrocannabinol

- VAS:

-

Visual Analog Scale

References

Bruggmann P, Grebely J. Prevention, treatment and care of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:22–S6. 014. PubMed PMID: WOS:000425828900005.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report– United States, 2020 2022, September [cited 2023 6/27/2023]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2020surveillance/hepatitis-c.htm.

Degenhardt L, Peacock A, Colledge S, Leung J, Grebely J, Vickerman P, et al. Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: a multistage systematic review. Lancet Global Health. 2017;5(12):E1192–E207. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30375-3. PubMed PMID: WOS:000414869500020.

Macias J, Morano L, Tellez F, Granados R, Rivero-Juarez A, Palacios R, et al. Response to direct-acting antiviral therapy among ongoing drug users and people receiving opioid substitution therapy. J Hepatol. 2019;71(1):45–51..018. PubMed PMID: WOS:000471646900008.

Litwin AH, Lum PJ, Taylor LE, Mehta SH, Tsui JI, Feinberg J, et al. Patient-centred models of hepatitis C treatment for people who inject drugs: a multicentre, pragmatic randomised trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(12):1112–27.

Norton BL, Akiyama MJ, Agyemang L, Heo M, Pericot-Valverde I-, Litwin AH, editors. Low adherence achieves high HCV cure rates among people who inject drugs treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Open Forum Infectious Diseases; 2020: Oxford University Press US.

Heo M, Pericot-Valverde I, Niu J, Norton BL, Akiyama MJ, Nahvi S, et al. More intensive hepatitis C virus care models promote adherence among people who inject drugs with active drug use: the PREVAIL study. J Viral Hepat. 2023;30(2):172–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.13756. Epub 20221012.

Stirratt MJ, Dunbar-Jacob J, Crane HM, Simoni JM, Czajkowski S, Hilliard ME, et al. Self-report measures of medication adherence behavior: recommendations on optimal use. Translational Behav Med. 2015;5(4):470–82.

Burton MJ, Voluse AC, Patel AB, Konkle-Parker D. Measuring adherence to hepatitis C direct-acting antiviral medications: using the VAS in an HCV treatment clinic. South Med J. 2018;111(1):45–50.

Pericot-Valverde I, Rennert L, Heo M, Akiyama MJ, Norton BL, Agyemang L, et al. Rates of perfect self‐reported adherence to direct‐acting antiviral therapy and its correlates among people who inject drugs on medications for opioid use disorder: the PREVAIL study. J Viral Hepatitis. 2021;28(3):548–57.

Cunningham EB, Amin J, Feld JJ, Bruneau J, Dalgard O, Powis J, et al. Adherence to sofosbuvir and velpatasvir among people with chronic HCV infection and recent injection drug use: the SIMPLIFY study. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;62:14–23.

Choo PW, Rand CS, Inui TS, Lee ML, Canning C, Platt R. A cohort study of possible risk factors for over-reporting of antihypertensive adherence. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2001;1:6. Epub 20011213. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-1-6. PubMed PMID: 11801191; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC64641.

Amico K, Mehrotra M, Avelino-Silva V, McMahan V, Veloso V, Anderson P, et al. Self-reported recent PrEP dosing and drug detection in an open label PrEP study. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(7):1535–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1360-7. PubMed PMID: WOS:000379000500017.

Baker Z, Javanbakht M, Mierzwa S, Pavel C, Lally M, Zimet G, et al. Predictors of over-reporting HIV pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) adherence among Young men who have sex with men (YMSM) in self-reported Versus Biomarker Data. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1174–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1958-4. PubMed PMID: WOS:000428954500012.

Litwin A, Jost J, Wagner K, Heo M, Karasz A, Feinberg J, et al. Rationale and design of a randomized pragmatic trial of patient-centered models of hepatitis C treatment for people who inject drugs: the HERO study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2019;87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2019.105859. PubMed PMID: WOS:000501656300006.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. Epub 2001/09/15.

Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams J, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder - the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. PubMed PMID: WOS:000237720500008.

Philip TJ, Crosby KM, Frank-Pearce SG, Wendelboe AM, Solberg M, Weakley J et al. Factors impacting medication adherence in a birth cohort at higher risk for Hepatitis C infection. Medicine. 2022;101(50).

Back D, Belperio P, Bondin M, Negro F, Talal AH, Park C, et al. Efficacy and safety of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir in patients with chronic HCV infection and psychiatric disorders: an integrated analysis. J Viral Hepatitis. 2019;26(8):951–60.

Kalin NH. The critical relationship between anxiety and depression. Am Psychiatric Assoc; 2020. pp. 365–7.

Martin-Santos R, Diez‐Quevedo C, Castellvi P, Navinés R, Miquel M, Masnou H, et al. De novo depression and anxiety disorders and influence on adherence during peginterferon‐alpha‐2a and Ribavirin treatment in patients with hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(3):257–65.

An A, Lee J, Sharpsten L, Wilson A, Cao F, Tran J. Impact of pill burden on adherence to hepatitis C medication. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(11):1937–44. PubMed PMID: WOS:000487650900001.

Lopes SS, Pericot-Valverde I, Arnsten J, Lum PJ, Taylor LE, Mehta SH, et al. Self-reported and measured adherence to hepatitis C direct-acting antiviral therapy and sustained virologic response among people who inject drugs: the HERO study. Int J Drug Policy. 2023;123:104288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.104288. Epub 20231215.

Youden W. Index for Rating Diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3(1):32–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1%3C32::AID-CNCR2820030106%3E3.0.CO;2-3. PubMed PMID: WOS:A1950UD97200004.

Adje Y, Brooks K, Castillo-Mancilla J, Wyles D, Anderson P, Kiser J. The use of technology-based adherence monitoring in the treatment of hepatitis C virus. Therapeutic Adv Infect Disease. 2022;9. https://doi.org/10.1177/20499361221095664. PubMed PMID: WOS:000798631500001.

Cunningham EB, Hajarizadeh B, Amin J, Litwin AH, Gane E, Cooper C, et al. Adherence to once-daily and twice-daily direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C infection among people with recent injection drug use or current opioid agonist therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(7):e115–e24.

Petersen T, Townsend K, Gordon L, Sidharthan S, Silk R, Nelson A, et al. High adherence to all-oral directly acting antiviral HCV therapy among an inner-city patient population in a phase 2a study. Hep Intl. 2016;10(2):310–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-015-9680-7. PubMed PMID: WOS:000371792100010.

Doró P, Benko R, Czakó A, Matuz M, Thurzó F, Soós G. Optimal recall period in assessing the adherence to antihypertensive therapy: a pilot study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(4):690–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-011-9529-7. Epub 20110621.

Ziff J, Vu T, Dvir D, Riazi F, Toribio W, Oster S, et al. Predictors of hepatitis C treatment outcomes in a harm reduction-focused primary care program in New York City. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18(1):1–8.

Eletreby R, Esmat G, Elsharkawy A, Alsehemy L, Mohamed R, Alem S, et al. HCV/HIV coinfected Egyptian patients: a cross-sectional study of their main characteristics and barriers to HCV treatment initiation. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2022;116(3):227–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/trstmh/trab106. PubMed PMID: WOS:000763624600005.

Frankova S, Jandova Z, Jinochova G, Kreidlova M, Merta D, Sperl J. Therapy of chronic hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: focus on adherence. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00519-y. PubMed PMID: WOS:000671233500002.

Mason K, Dodd Z, Guyton M, Tookey P, Lettner B, Matelski J, et al. Understanding real-world adherence in the directly acting antiviral era: a prospective evaluation of adherence among people with a history of drug use at a community-based program in Toronto, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;47:202–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.025. PubMed PMID: WOS:000412613000025.

Schwarz T, Horvath I, Fenz L, Schmutterer I, Rosian-Schikuta I, Mardh O. Interventions to increase linkage to care and adherence to treatment for hepatitis C among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and practical considerations from an expert panel consultation. Int J Drug Policy. 2022;102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103588. PubMed PMID: WOS:000784286500017.

Mason K, Dodd Z, Sockalingam S, Altenberg J, Meaney C, Millson P, et al. Beyond viral response: a prospective evaluation of a community-based, multi-disciplinary, peer-driven model of HCV treatment and support. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(10):1007–13. PubMed PMID: WOS:000362858500014.

Sylvestre DL, Clements BJ, Malibu Y. Cannabis use improves retention and virological outcomes in patients treated for hepatitis C. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18(10):1057–63.

Fischer B, Reimer J, Firestone M, Kalousek K, Rehm J, Heathcote J. Treatment for hepatitis C virus and cannabis use in illicit drug user patients: implications and questions. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18(10):1039–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.meg.0000236869.93527.b9. PubMed PMID: 16957507.

Funding

This work was supported by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award [grant number HPC-1503-28122] with additional support by Gilead Sciences, Quest Diagnostics, Monogram Biosciences, and OraSure Technologies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SSL: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing-original draft, review & editing. IP-V: Conceptualization, Writing-review & editing. PJL: Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition. LET: Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition. SHM: Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition. JIT: Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition. JF: Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition. AYK: Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition. BLN: Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition. KP: Writing-review & editing, Data curation, Funding acquisition. CM-K: Writing-review & editing, Data curation. J Anderson: Data curation. AK: Writing-review & editing. J Arnsten: Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition. PM: Writing-review & editing. MH: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing-review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. AHL: Conceptualization, Writing-review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The HERO study was approved by the IRBs at each of the study sites listed below, and informed consent to participate was obtained from all study participants.

(1) West Virginia University: 1609287809

(2) Brown University: 901973-2, 3

(3) John Hopkins: 00007239

(4) Massachusetts General Hospital: 2016P002442/PHS

(5) Montefiore Medical Center: 2015-5723

(6) University of California, San Francisco: 16-20016

(7) University of New Mexico: 16-235

(8) University of Washington: STUDY00002659

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

JF has received research grant support from Gilead Sciences. AYK has served on advisory boards for Biomarin. AHL has served on advisory boards for Gilead Sciences and Merck Pharmaceuticals and received research funding from Gilead Sciences. SHM has received speaker fees from Gilead Sciences. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lopes, S.S., Pericot-Valverde, I., Lum, P.J. et al. Overreporting of adherence to hepatitis C direct-acting antiviral therapy and sustained virologic response among people who inject drugs in the HERO study. BMC Infect Dis 24, 251 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09124-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09124-3