Abstract

Background

Pulmonary cryptococcosis (PC) rarely occurs in immunocompetent children.

Case presentation

A 13-year-old boy was admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of Ningbo University in February 2023 with complaints of cough and chest pain. Physical examination showed slightly moist rales in the right lung. Chest computed tomography (CT) suggested a lung lesion and cavitation. Blood routine test, lymphocyte subsets, immunoglobulin, and complement tests indicated that the immune system was normal. However, the serum cryptococcal antigen test was positive. Next-generation sequencing revealed Cryptococcus infection. The child was diagnosed with PC and was discharged after treating with fluconazole 400 mg. Four months later, chest CT showed that the lung lesion diminished, and reexamination of serum cryptococcal antigen test turned positive.

Conclusion

PC should be considered in an immunocompetent child with pulmonary cavities with nonspecific symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cryptococcosis is a systemic opportunistic fungal infection that occurs frequently in immunocompromised individuals [1]. It is contracted by inhaling a fungus in the Cryptococcus genus that can be found in the excrement of birds such as pigeons and parrots. Cryptococcus can also be found in fruits and vegetables, as well as on pets, cockroaches, and other animals [2]. There have been very few reports of Cryptococcus pneumonia in immunocompetent humans recently [3]. Data on its occurrence in children are even more limited, particularly in developing countries [4]. Therefore, the diagnosis of cryptococcosis in immunocompetent children is challenging. The clinical symptoms of pulmonary cryptococcosis (PC) are nonspecific and frequently manifest as fever, cough, dyspnea, chest pain, and abdominal pain. However, PC can also present as asymptomatic. Thus, cryptococcosis is easily misdiagnosed or ignored. This study presented a case of cryptococcosis with pulmonary cavities in an immunocompetent child.

Case presentation

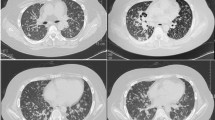

A 13-year-old boy was admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of Ningbo University in February 2023 with complaints of cough and chest pain. He had no history of disease or poultry contact. Physical examination showed that he was 173 cm tall and weighed 80 kg, with clear consciousness, a scar of Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination, and slightly moist rales in the right lung. There were no abnormalities in routine blood test or blood chemistry. Immunoglobulin and complement tests showed normal IgE levels and lymphocyte subsets. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 2 mm/h, and the tuberculosis-SPOT test was negative. The results of the rheumatoid test, as well as the tests for syphilis, hepatitis B, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies, were all negative. In addition, the 13 respiratory pathogen tests also yielded negative results. The aspergillus IgG antibody and galactomannan tests were both negative. However, the serum cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) test, performed by gold immunochromatography assay (Trade name: CrAg Lateral Flow Assay; Product code: CR2003; Manufacturer: Immuno-Mycologics, Inc) was positive 2 days after admission. Both routine and biochemical test of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed normal results, and india ink staining for Cryptococcus was negative. Blood culture, CSF culture, and sputum culture were all negative. Cardiac ultrasound, electrocardiogram, cerebral magnetic resonance imaging, and fiber bronchoscopy revealed no significant abnormalities. A chest ultrasound revealed heterogeneous echoes in the right thoracic cavity with possible inflammatory wrapping. The chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a lesion and cavities in the right lower lobe of the lung (Fig. 1a). Bronchoscopy showed that the cavity was unobstructed. In light of the unexplained pulmonary cavitation, absence of abnormalities in the appearance of the tracheal structure, and a positive blood CrAg test, alveolar lavage fluid was subjected to next-generation sequencing (NGS) for a definitive diagnosis. This was done to exclude false positives and determine the underlying cause of the disease. BALF samples with a total cell concentration of ≥1 × 106 cells/mL underwent pre-processing for host removal using sample release reagent (Genskey Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Subsequently, DNA was extracted from 0.3 mL BALF samples following the instructions of the DNA Extraction and Purification Kit (Genskey Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The DNA library was generated after cDNA synthesis, and its quality was assessed through Qubit detection. Finally, the qualified library was sequenced on an MGISEQ200 platform (MGI Tech Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). Adapters and low-quality reads (Q, 20) were removed from raw data with 50-bp single-end reads using fastp software. Human sequence data were excluded by mapping onto the human reference database (hg38, YH genome, T2T-CHM13 genome) through Burrows Wheeler Aligner (BWA) software. The remaining sequence reads, aligned to the Dian Diagnostics Pathogenic Microorganism Genome Database by BWA, underwent annotation and statistical analysis. Negative controls (Genskey Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) underwent the same sequencing and bioinformatics analysis procedures as the clinical samples. Synthesized sequences were used as a positive control, serving as indicators for the detection process in each batch. For homogenized species-specific sequences, the prevalence of microbiota was determined according to the mNGS criteria. For clinical core pathogens and bacteria difficult to detect, including firmicutes and intracellular bacteria, reads ≥1 were considered positive. For other clinically relevant bacteria, fungi, and viruses, reads ≥3, exceeding those in the negative controls of the same batch, were considered positive. For bacteria, fungi, and viruses not clinically reported or isolated, reads ≥20, surpassing those in the negative controls of the same batch, were considered positive. The NGS test detected Cryptococcus species in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid at 3 days after admission (Table 1). As the cryptococcal infection was confined to the lungs, PC was the definitive diagnosis. He was treated with intravenous injection of fluconazole at 400 mg once a day for 8 days, followed by continuous oral administration of fluconazole capsules at 400 mg once a day for 6 months. The child’s symptoms, including chest pain, were significantly relieved. He was discharged 10 days after admission without coughing or chest pain. Chest CT revealed that the lesion in the lower lobe of the right lung reduced after taking fluconazole for 1 month (Fig. 1b). The lesion in lung diminished and reexamination of serum CrAg turned positive after taking fluconazole for 4 months (Fig. 1c).

Images. a CT on admission showed a lesion and cavities in the right lower lobe of the lung, suggesting infection. b CT on the recovery phase (after taking fluconazole orally for 1 month) showed the lesion in the lower lobe of the right lung had reduced. c CT on the recovery phase (after taking fluconazole orally for 4 month) showed the inflammation in the lower lobe of the right lung had well absorbed

Discussion

This case presented an immunocompetent child with PC manifested by pulmonary cavities, who were diagnosed by NGS and cured with fluconazole.

PC is a fungal lung disease caused by the inhalation of Cryptococcus spores. It can occur in both immunocompromised individuals and immunocompetent hosts, but T-cell deficiency confers the most susceptibility [5]. The diagnosis of PC is challenging, and it is often misdiagnosed as other diseases, including pneumonia, lung abscess, tuberculosis, or lung malignant tumor [6]. Previous studies reported consistent radiological manifestations of PC in children compared with those in adults, with localized nodular lesions being the most frequent radiographic finding in the chest [7]. There are several reports of PC in immunocompetent children [2, 4, 8, 9]. PC can present as an intrapulmonary cavity with an incidence of 11.0–34.6% [10,11,12] as this case presented. A similar case of a Chinese 16-year-old girl reported bilateral diffuse cavity nodules [8]. The common chest imaging of PC includes nodule, masses, consolidation, and pleural effusion [13,14,15]. In addition, abnormal imaging findings of cryptococcosis, such as nodules, pulmonary infiltration, hilar lymph node enlargement, and pulmonary cavity, were also found in tuberculosis [16]. It is important that health professionals become familiar with these diseases since they are becoming more important around the world as a result of travel and immigration [17] (Table 2). Previous case reports of PC in immunocompetent children are scarce, but boys aged between 5 and 17 years seemed more affected [2, 4, 18], which was consistent with this case.

The clinical symptoms of PC may be similar to those of tuberculosis, leading to misdiagnosis [19], particularly in areas with high incidences of tuberculosis, such as Asia and Africa [4]. In most cases, delayed diagnosis leads to death [20]. It has been reported that five of the 11 patients with cryptococcosis who were misdiagnosed as having tuberculosis died due to delayed diagnosis and the start of antifungal therapy [21]. This was the first time NGS was employed for the diagnosis of PC. Typically, PC is diagnosed through histological results, fungal cultures, serum CrAg, and imaging [22]. However, in this particular case, NGS, rarely utilized in previous cases, played a crucial role in achieving an early and definitive diagnosis of PC. This contribution proved instrumental in improving the overall outcome.

In this study, the patient presented with respiratory symptoms such as cough and chest pain. In addition, if not detected and treated promptly, cryptococcosis can result in life-threatening disseminated infection and respiratory failure [3]. According to statistics, annually there are 220,000 cases of cryptococcal meningitis in immunocompromised individuals, leading to nearly 180,000 deaths [23]. The incidence of PC increased by more than six times within several years, reaching 38 cases per million in 2006, among whom most of the increased cases are HIV-negative [24]. A study in Uganda reported 11% of patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection developed PC [25]. In mainland China, 15.7% of the cryptococcosis patients were AIDS or HIV-infected [26], while 60% of PC cases were diagnosed in immunocompetent non-HIV patients [27]. A recent study reported the most common types of Cryptococcus infections in Southern China were cryptococcal meningitis, cryptococcal fungemia, and PC, and only 12 out of the 170 patients had autoimmune disorders [28]. According to the local Health Department in the Ningbo city, there were 9 cases of adult with PC over the past year, all with normal immune function, and the present case was the only case of PC in child. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic may increase the number of patients at risk [29], and PC was diagnosed 1 month after a novel coronavirus infection.

Cryptococcosis is usually diagnosed by microscope, immunology, or microbiology [30]. Direct detection of ink staining is a rapid, low-cost method for detecting Cryptococcus neoformans. Although the specificity is high, the sensitivity about 86% depends on the user, and it is inadequate for detecting early fungal infection [31]. In recent years, CrAg test, a rapid and sensitive diagnostic method, has received increasing attention as a novel diagnostic tool for PC [32] and recommended by guideline [33]. However, in some cases of non-disseminated PC, CrAg may not be detected despite the presence of infection [7]. In this case, the infection was limited to the lungs, but a positive CrAg test was detected. Therefore, CrAg testing cannot be ignored in PC patients, and a negative result should not necessarily rule out cryptococcal infection. Although PC in immunocompetent adults may resolve on its own, children have relatively underdeveloped immunity, which increases the risk of dissemination. Consequently, active antifungal therapy is recommended for pediatric PC. Fluconazole has high bioavailability and fewer side effects. Therefore, it is recommended as the first-line treatment for PC in immunocompetent children [9]. In this case, the blood cryptococcal antigen was still positive in the outpatient follow-up up to 4 months. Several studies suggested that it took more than 1 year for the blood CrAg to turn negative in the adult department [32].

C. neoformans var. grubii serotype A represented over 80% of all Cryptococcus globally [34]. However, East Asian countries reported more cryptococcal polymorphisms than Southeast Asian countries [35, 36].

In conclusion, a diagnosis of PC should be considered in immunocompetent children present with pulmonary cavities and nonspecific symptoms. NGS test and early treatment of fluconazole would be helpful to a better prognosis.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Abbreviations

- PC:

-

Pulmonary cryptococcosis

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- CrAg:

-

Cryptococcal antigen

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

References

Paes HC, Derengowski LDS, Peconick LDF, Albuquerque P, Pappas GJ Jr, Nicola AM, et al. A Wor1-like transcription factor is essential for virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:369.

Bauer S, Kim JE, La KS, Yoo Y, Lee KH, Park SH, et al. Isolated pulmonary cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent boy. Korean J Pediatr. 2010;53:971–4.

Haider MS, Master M, Mahtani A, Guzzo E, Khalil A. Cryptococcal pneumonia in an immunocompetent patient: a rare occurrence. Cureus. 2022;14:e29841.

Nakatudde I, Kasirye P, Kiguli S, Musoke P. It is not always tuberculosis! A case of pulmonary cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent child in Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2021;21:990–4.

Beardsley J, Dao A, Keighley C, Garnham K, Halliday C, Chen SC, et al. What's new in Cryptococcus gattii: from bench to bedside and beyond. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;9.

Sousa C, Marchiori E, Youssef A, Mohammed TL, Patel P, Irion K, et al. Chest imaging in systemic endemic mycoses. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8.

Setianingrum F, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Denning DW. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: a review of pathobiology and clinical aspects. Med Mycol. 2019;57:133–50.

Huang J, Li H, Lan C, Weng H. Disseminated cryptococcal infection with pulmonary involvement presenting as diffuse cavitary nodules in an immunocompromised patient: a case report. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23:38.

Zhang XY, Zhao SY, Zhou CJ. Case Report: Three Pediatric Pulmonary Cryptococcosis Patients with Prominent Manifestation of Mediastinal Lymphadenopathy. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2021;52:859–61.

Chen LA, She DY, Liang ZX, Liang LL, Chen RC, Ye F, et al. A prospective multi-center clinical investigation of HIV-negative pulmonary cryptococcosis in China. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2021;44:14–27.

Kohno S, Kakeya H, Izumikawa K, Miyazaki T, Yamamoto Y, Yanagihara K, et al. Clinical features of pulmonary cryptococcosis in non-HIV patients in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2015;21:23–30.

Wang BQ, Zhang HZ, Fan BJ, al. e. Meta-analysis of clinical manifesta- tions of pulmonary cryptococcosis in China mainland. Chin. J Clin Med. 2013;20:351–4.

Zhang Y, Li N, Zhang Y, Li H, Chen X, Wang S, et al. Clinical analysis of 76 patients pathologically diagnosed with pulmonary cryptococcosis. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1191–200.

Yu JQ, Tang KJ, Xu BL, Xie CM, Light RW. Pulmonary cryptococcosis in non-AIDS patients. Braz J Infect Dis. 2012;16:531–9.

Zinck SE, Leung AN, Frost M, Berry GJ, Müller NL. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: CT and pathologic findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:330–4.

Howard-Jones AR, Sparks R, Pham D, Halliday C, Beardsley J, Chen SC. Pulmonary Cryptococcosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8.

Kunin JR, Flors L, Hamid A, Fuss C, Sauer D, Walker CM. Thoracic endemic Fungi in the United States: importance of patient location. Radiographics. 2021;41:380–98.

Sweeney DA, Caserta MT, Korones DN, Casadevall A, Goldman DL. A ten-year-old boy with a pulmonary nodule secondary to Cryptococcus neoformans: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:1089–93.

Adsul N, Kalra KL, Jain N, Haritwal M, Chahal RS, Acharya S, et al. Thoracic cryptococcal osteomyelitis mimicking tuberculosis: a case report. Surg Neurol Int. 2019;10:81.

Ismail J, Chidambaram M, Sankar J, Agarwal S, Lodha R. Disseminated Cryptococcosis presenting as Miliary lung shadows in an immunocompetent child. J Trop Pediatr. 2018;64:434–7.

Ekeng BE, Davies AA, Osaigbovo II, Warris A, Oladele RO, Denning DW. Pulmonary and Extrapulmonary manifestations of fungal infections misdiagnosed as tuberculosis: the need for prompt diagnosis and management. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8.

Cox GM, Perfect JR. Cryptococcus neoformans infection outside the central nervous system. In: up- ToDate, Kauffman CA, Kaplan SL (Ed), UpToDate. Waltham, MA. (Accessed 12 June 2020).

Seyer Cagatan A, Taiwo Mustapha M, Bagkur C, Sanlidag T, Ozsahin DU. An alternative diagnostic method for C. Neoformans: preliminary results of deep-learning based detection model. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;13.

Pyrgos V, Seitz AE, Steiner CA, Prevots DR, Williamson PR. Epidemiology of cryptococcal meningitis in the US: 1997-2009. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56269.

Deok-jong Yoo S, Worodria W, Davis JL, Cattamanchi A, den Boon S, Kyeyune R, et al. The prevalence and clinical course of HIV-associated pulmonary cryptococcosis in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54:269–74.

Yuchong C, Fubin C, Jianghan C, Fenglian W, Nan X, Minghui Y, et al. Cryptococcosis in China (1985-2010): review of cases from Chinese database. Mycopathologia. 2012;173:329–35.

Liu K, Ding H, Xu B, You R, Xing Z, Chen J, et al. Clinical analysis of non-AIDS patients pathologically diagnosed with pulmonary cryptococcosis. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:2813–21.

Bilal H, Zhang D, Shafiq M, Khan MN, Chen C, Khan S, et al. Cryptococcosis in southern China: insights from a six-year retrospective study in eastern Guangdong. Infect Drug Resist. 2023;16:4409–19.

Isaac S, Pasha MA, Isaac S, Kyei-Nimako E, Lal A. Pulmonary Cryptococcosis and pulmonary fibrosis: a complication of COVID-19 pneumonia. Cureus. 2023;15:e35660.

Almeida-Paes R, Bernardes-Engemann AR, da Silva MB, Pizzini CV, de Abreu AM, de Medeiros MM, et al. Immunologic diagnosis of endemic mycoses. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8.

Rajasingham R, Wake RM, Beyene T, Katende A, Letang E, Boulware DR. Cryptococcal meningitis diagnostics and screening in the era of point-of-care laboratory testing. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57.

Choi HS, Kim YH, Jeong WG, Lee JE, Park HM. Clinicoradiological features of pulmonary Cryptococcosis in immunocompetent patients. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2023;84:253–62.

WHO guidelines approved by the guidelines review committee. Guidelines for diagnosing, preventing and managing Cryptococcal disease among adults, adolescents and children living with HIV. Geneva: World Health Organization © World Health Organization; 2022.

Antinori S. New insights into HIV/AIDS-associated Cryptococcosis. Isrn aids. 2013;2013:471363.

Pan W, Khayhan K, Hagen F, Wahyuningsih R, Chakrabarti A, Chowdhary A, et al. Resistance of Asian Cryptococcus neoformans serotype a is confined to few microsatellite genotypes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32868.

Khayhan K, Hagen F, Pan W, Simwami S, Fisher MC, Wahyuningsih R, et al. Geographically structured populations of Cryptococcus neoformans variety grubii in Asia correlate with HIV status and show a clonal population structure. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72222.

Chen J, Zhang MJ, Ge XH, Liu YH, Jiang T, Li J, et al. Disseminated cryptococcosis with multiple and mediastinal lymph node enlargement and lung involvement in an immunocompetent child. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2019;11:293–6.

Yao K, Qiu X, Hu H, Han Y, Zhang W, Xia R, et al. Pulmonary cryptococcosis coexisting with central type lung cancer in an immuocompetent patient: a case report and literature review. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20:161.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This study was supported by the “Spearhead Plan” of Zhejiang Province, the research on intelligent diagnosis and treatment system of major diseases based on IT/BT fusion (No. 2023C03009), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62076218).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QD carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript. Qianqian Ying performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. YW and Qidong Ye participated in acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This work was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Ningbo University (# 2023 Research No. 085RS).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the legal representative of this patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, Q., Wang, Y., Ying, Q. et al. Cryptococcosis with pulmonary cavitation in an immunocompetent child: a case report and literature review. BMC Infect Dis 24, 162 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09061-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09061-1