Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has disrupted multiple health services, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing, care, and treatment services, jeopardizing the achievement of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS 90-90-90 global target. While there are limited studies assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people living with HIV (PLHIV) in Latin America, there are none, to our knowledge, in Venezuela. This study aims to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among PLHIV seen at the outpatient clinic of a reference hospital in Venezuela.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study among PLHIV aged 18 years and over seen at the Infectious Diseases Department of the University Hospital of Caracas, Venezuela between March 2021 and February 2022.

Results

A total of 238 PLHIV were included in the study. The median age was 43 (IQR 31–55) years, and the majority were male (68.9%). Most patients (88.2%, n = 210) came for routine check-ups, while 28 (11.3%) were newly diagnosed. The majority of patients (96.1%) were on antiretroviral therapy (ART), but only 67.8% had a viral load test, with almost all (95.6%) being undetectable. Among those who attended regular appointments, 11.9% reported missing at least one medical consultation, and 3.3% reported an interruption in their ART refill. More than half of the patients (55.5%) had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, while the rest expressed hesitancy to get vaccinated. Most patients with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy were male (65.1%), younger than 44 years (57.5%), employed (47.2%), and had been diagnosed with HIV for less than one year (33%). However, no statistically significant differences were found between vaccinated patients and those with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Older age was a risk factor for missing consultations, while not having an alcoholic habit was identified as a protective factor against missing consultations.

Conclusion

This study found that the COVID-19 pandemic had a limited impact on adherence to medical consultations and interruptions in ART among PLHIV seen at the University Hospital of Caracas, Venezuela.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) remains a significant global public health problem, with approximately 39 million people living with HIV (PLHIV) and 630,000 acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related deaths in 2022 [1]. The introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been a game-changer in the fight against HIV. Highly effective drugs with improved pharmacokinetics and tolerability have enhanced the prognosis and quality of life for PLHIV, contributing to a 68.5% decline in AIDS-related deaths worldwide between 2004 and 2022 [1]. Since 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended dolutegravir-based regimens as first- and second-line treatments for all PLHIV due to their high efficacy and favorable toxicity profile [3]. However, the use of these regimens has been primarily limited to high-income countries [4].

Venezuela has experienced the highest rate of ART interruptions among Latin American countries since 2016, with the situation worsening in 2017 and 2018 due to limited access to ART, with only 16% of patients receiving treatment by April 2018 [5]. However, through the efforts of nongovernmental organizations and the implementation of the Master Plan for the Strengthening of the Response to HIV, Tuberculosis, and Malaria in Venezuela [6], nationwide access to dolutegravir-based ART was resumed in February 2019. Despite this progress, monitoring of the efficacy and tolerability of this regimen in both treatment-experienced and newly diagnosed patients has been limited. Strict adherence to ART is crucial for maintaining an undetectable viral load, reducing the risk of progression to AIDS and transmission of HIV to sexual partners [7]. However, epidemiological surveillance related to access to diagnosis, treatment, and viral suppression remains limited in Venezuela.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had significant direct and indirect impacts on global health, particularly in low- and middle-income countries [8, 9], including Venezuela, where the effects are compounded by a complex humanitarian crisis, weakened health systems, and concurrent epidemics such as HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis [5]. In some countries, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted HIV testing, care [9,10,11], and treatment [12] services, potentially leading to increased HIV-related deaths and transmission, and jeopardizing progress towards the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS 90-90-90 global target [13]. Moreover, despite that several studies showing that COVID-19 vaccination is effective in preventing these adverse outcomes [14,15,16,17], vaccine hesitancy remains a global problem [18], particularly among higher-risk populations such as PLHIV. Concerns about vaccine safety have been identified as a primary factor contributing to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among this population [19, 20].

Currently, there is limited information available on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on PLHIV in Venezuela. Additionally, the rate of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among this population is unknown. This study aims to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among PLHIV seen at the outpatient clinic of the Infectious Diseases Department at the University Hospital of Caracas during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic in Venezuela.

Methods

Study design and patients

A cross-sectional study was conducted between March 2021 and February 2022 at the outpatient clinic of the Infectious Diseases Department at the University Hospital of Caracas, Venezuela. This specialized outpatient clinic, which began operating in 1990, provides care for patients with HIV infection and is considered the largest in the country, having attended a total of 6,350 patients in 2022. The study included consecutive patients aged 18 years and over with either known HIV infection or newly diagnosed with a positive HIV result. According to the Statistics Department of the University Hospital of Caracas, in 2021 there were 5,346 outpatient consultations of PLHIV. To analyze this population with a 95% confidence interval and a margin of error of 5%, a sample size of at least 359 participants was required. The sampling method employed was non-probabilistic.

Survey design and data collection

A data collection form was designed to gather both sociodemographic and clinical data. Sociodemographic data collected included age, sex, origin by state, education level, marital status, occupation, income in US$ per month, sexual orientation, and whether the individual had a stable partner. Clinical data collected included time since HIV diagnosis, comorbidities, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) history, AIDS-associated diseases history, recommended vaccination history, current ART, previous ART regimen, post-ART viral load, post-ART CD4+ count, and weekly treatment adherence. Additionally, information related to COVID-19 and the COVID-19 pandemic was also collected. This included COVID-19 history and severity, COVID-19 vaccination status and reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, problems related to compliance with consultations in the last 12 months, and ART refilling during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data analysis

Participant data were summarized using descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation (SD), median, interquartile range (IQR), and/or frequency, percentage (%). The normality of numeric variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Univariable analyses were performed using tests such as the Mann-Whitney U test for numerical variables with a non-normal distribution, Student’s t-test for those with a normal distribution, and Pearson’s chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Statistically significant variables identified in the univariable analyses were included in a binomial logistic regression using the enter method to identify factors associated with missed consultations. The best model was selected based on the highest percentage of participants including goodness of fit, R2 Nagelkerke, and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 26 (International Business Machines Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Sociodemographic and epidemiologic characteristics of PLHIV

A total of 238 patients were analyzed, of which 210 came for a follow-up appointment, including eight who were returning to their controls after having abandoned treatment. The remaining 28 patients were coming to their first appointment for ART initiation. The median age of the patients was 43 (IQR 31–55) years, with the majority being male (68.9%) and heterosexual (50%). Most patients came from the Capital District (45.8%) and Miranda state (45.4%). Almost half of them had a steady partnership, and among these partners, 52.1% (n = 60/115) had negative HIV serology, 40.9% (n = 47/115) had positive HIV serology, and 7% (n = 8/115) were unaware of their HIV status. Additional sociodemographic data may be found in Table 1.

Clinical information and ART history

The most frequent comorbidity among patients was hypertension (11.8%, n = 28), followed by osteoporosis (5%, n = 12), asthma (3.4%, n = 8), and diabetes (2.5%, n = 6). In relation to STDs history, syphilis was identified as the most frequent (19.3%, n = 46), followed by human papillomavirus infection. A tuberculosis history, both intra- and extrapulmonary, was the most frequent AIDS-associated disease (10.5%, n = 25). In relation to compliance with the recommended vaccines for PLHIV, the least compliant was the pneumococcal vaccine (Table 2).

Regarding ART, excluding newly diagnosed patients who were started on treatment for the first time (n = 28), almost all patients (96.1%, n = 202) were on ART. The majority of these patients (91%) were receiving the combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, lamivudine, and dolutegravir (TLD), followed by the combination of abacavir, lamivudine, and dolutegravir (8.9%). Only eight patients with a known HIV diagnosis were off treatment because they had discontinued it. One hundred and fifty-five patients had been previously exposed to ART, with a mean of 1.5 (SD 1.5, range: 1–7) previous regimens. The most frequent previous regimen was the combination of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) plus non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) in 51% of patients (n = 79). Out of the patients on ART (n = 202), only 137 had available viral load data (67.8%) and almost all of these patients had undetectable viral loads (< 200 copies of RNA, 95.6%, n = 131). The undetectability rate was 95.8% (n = 115/120) for patients on the TLD regimen and 94.1% (n = 16/17) for those on the abacavir, lamivudine, and dolutegravir regimen. Only 22 out of 202 patients (10.9%) had a CD4+ count available. Finally, adequate adherence was observed in most patients (84.1%, n = 170/202), but 32 patients (15.8%) reported skipping at least one dose per week (Table 3).

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on PLHIV

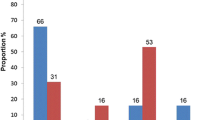

Only 43 patients (18.1%) reported having had severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, most of them diagnosed clinically (60.5%) without a confirmatory test and experiencing mild clinical manifestations (83.7%). Regarding COVID-19 vaccination, more than half of the patients (55.5%, n = 132) had received at least one dose of the vaccine (Table 4). Of these patients, 25 (18.9%) had received one dose, 92 (69.7%) had received two doses, and only 15 (11.4%) had received three doses. Among the unvaccinated group (44.5%, n = 106), all were hesitant to get vaccinated. Of these patients, 77 (72.6%) were unsure about getting vaccinated and wanted to consult with their doctor, while 29 (27.4%) preferred not to be vaccinated for distinct reasons: 23 (79.3%) expressed fear, four (13.8%) reported distrust, and four (13.8%) stated that they did not need it.

Most patients with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy were male (65.1%), younger than 44 years old (57.5%), employed (47.2%), with a monthly income between US$21–100 (47.2%), and had been diagnosed with HIV for less than one year (33%), but there were no statistically significant differences when compared to the vaccinated group. The proportion of patients with an HIV diagnosis of less than one year was higher among those with vaccine hesitancy (33%) compared to vaccinated patients (18.9%). In contrast, the proportion of patients with a diagnosis of 16 or more years was more frequent among vaccinated patients (31.1%) compared to those with vaccine hesitancy (17%). However, these differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.053). Although the proportion of patients with comorbidities was higher in the vaccinated group (40.2%) compared to the vaccine hesitancy group (29.2%), there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups (p = 0.08) (Table 5).

C

In relation to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on PLHIV who came to the consultation, only patients who came for control appointments were analyzed (n = 210). Of these patients, 11.9% (n = 25/210) reported having missed at least one medical consultation due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions; of these patients, 92% (n = 23/25) missed their appointment due to restricted mobility, another 8% (n = 2/25) due to fear of becoming infected, and one because they were outside the country. The median number of consultations in the last 12 months for these patients was 1 (IQR 1–2) consultation per patient. A model was performed to evaluate factors associated with missed consultations (p = 0.01, R2 Nagelkerke = 0.34, Hosmer–Lemeshow test = 0.457), and found that older age was a risk factor for missing consultations (OR = 1.058, 95% CI = 1.009–1.11, p = 0.019). Additionally, not having an alcoholic habit was identified as a protective factor against missing consultations (OR = 0.012, 95% CI = 0.001–0.108, p < 0.001) (Table 6). Only 3.3% of patients reported interruption of ART refill due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all reporting that they were unable to claim their medication refill due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions.

Discussion

This study describes the epidemiological and clinical behavior of PLHIV at the Hospital University of Caracas, Venezuela and estimates the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on disruptions in care, ART, and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. The majority of patients were young, employed men, consistent with previous reports [21,22,23]. Nearly half had a tertiary level of education, yet three-quarters earned less than US$100 per month, insufficient for access to basic food necessities [24]. Most patients were in heterosexual relationships [21, 22], with almost half reporting a stable partner. Nearly half of these partnerships were HIV serodiscordant, similar to other studies [25, 26]. Some studies reported substantial interruptions in pre-exposure prophylaxis (27.8–56%) during COVID-19 restrictions [27,28,29,30]. However, Venezuela does not have a pre-exposure prophylaxis program.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the diagnosis, care, and treatment of HIV infection has been extensively explored in other countries [31,32,33,34]. In general, new HIV diagnoses decreased by 12–45% [35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. In this study, a quarter of patients were recently diagnosed (< 1 year), emphasizing the importance of maintaining diagnostic and care activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Adherence to ART and undetectability rates were similar to those reported in other Latin American countries such as Peru [42], Brazil [30, 43], Argentina [44], and globally during the COVID-19 pandemic [41, 43, 45]. Despite WHO recommendations for continuity of HIV services during the COVID-19 pandemic [46], care and treatment have faced challenges worldwide. Unlike other countries [41, 47,48,49], we did not use telemedicine due to barriers such as lack of equipment and inconsistent internet access. Instead, we maintained face-to-face consultations with strict biosecurity measures and provided ART refills for longer periods, as documented in other countries [50].

The COVID-19 pandemic has variably impacted clinical appointments for PLHIV. Many patients have missed HIV clinical visits, support meetings, follow-up tests, and counseling services [51,52,53,54,55,56]. In a multi-country survey, 55.8% of PLHIV were unable to meet their HIV physician face-to-face in the past month [51]. In Mexico, 44.3% of patients experienced follow-up failures due to structural barriers such as transportation difficulties and distance to the hospital [57]. In Peru, 37.2% reported difficulty accessing routine HIV care, with the most common reason being temporary closure of their primary HIV clinic [42]. A study in Atlanta (GA, USA) found that 19% of PLHIV had missed a scheduled HIV care appointment in the previous 30 days [58], while another study among men who have sex with men in 20 countries reported that 20% of PLHIV were unable to access their HIV care provider, even via telemedicine [27]. In contrast, this study documented a lower impact on non-compliance with medical consultations (11.9%), possibly due to the non-prolonged interruption of consultation services and greater regularization of services after the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, as has been documented in other studies [41, 55]. Older age was significantly associated with missed visits, contrasting with COVID-19 pre-pandemic studies where missed visits were associated with younger age [59, 60]. Other COVID-19 pandemic-related factors such as inadequate transport, police abuse, insufficient transportation funds [61], lockdowns [62], limited access to health services, reduced income, inability to afford travel to health facilities or facemasks, fear of COVID-19 [54], and fear of visiting hospitals [55] could have had a greater impact on the life stability of older PLHIV. This instability has been correlated with a higher risk of missed medical appointments compared to their peers with less life chaos [63].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, ART-producing pharmaceutical companies faced challenges with international shipping due to border restrictions, transportation delays, increased lead times, and rising costs, contributing to global ART disruptions [64, 65]. However, surveys and observational studies have shown variability in ART refill interruptions. A global study in 20 countries reported that more than half were unable to access ART refills remotely, with the least access in Belarus, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Mexico, and Russia [27]. In Ethiopia, 27.4% of participants missed visits for refills [54], while in Peru, 24% reported difficulty picking up their ART due to cancelled appointments or lack of transportation [42]. A study in Italy documented a 23.1% decrease in dispensed ART during early 2020 compared to 2019, but this trend normalized after the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic [41]. Similarly, a study in Haiti observed an 18% decline in ART refills [50], while in Brazil, only 17.2% reported an impact on ART refills [30]. In Taiwan, only 9.1% of PLHIV self-reported interrupted ART [48], while this study found that only 3% experienced interruption as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, similar to reports from Brazil [43], Argentina [44], Northern Italy [41], and Indonesia [55] (4.2%, 3.9%, 3.2%, and 3%, respectively). A multi-country survey among PLHIV reported that 3.6% were unable to refill their ART [51], while a similar study in China found that 2.7% experienced interruption with a median duration of 3 (IQR 1–6) days and higher risk for those with a treatment abandonment history [66]. The low rate of interruption in this study may be due to continued operation of the ARV dispensary during the COVID-19 pandemic and the strategy of providing three months of ART at a time, as implemented in other countries [50, 66]. Thus, evidence of HIV care disruption and ART interruption during the COVID-19 pandemic was primarily during the early months and varied by region depending on measures implemented by each country. Despite these interruptions (self-reported or electronically recorded), adherence was maintained in several studies [30, 42, 43].

Although studies have shown discrepancies, PLHIV appear to be at high risk for adverse clinical outcomes from COVID-19, with some evidence of higher hospitalization and mortality rates [67,68,69]. Despite the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination in preventing these outcomes [14,15,16,17], almost half (44.5%) of participants in this study expressed vaccine hesitancy due to fear and mistrust, similar to reasons reported in Latin America [70], the USA, India, and China [71,72,73]. The rate of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among PLHIV in this study was lower than in Nigeria (57.7%) but higher than in India (38.4%) [73], France (28.7%) [74], China (27.5%) [75], Trinidad and Tobago (39%) [76], Brazil (23.9%) [51], and other Latin American countries (12.8%) [70]. Most patients with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy were low-income young men with recent HIV diagnoses, consistent with other studies [19]. The highest proportion of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was found among those with recent diagnoses (< 1 year), possibly due to lack of knowledge about COVID-19 vaccination and HIV infection [77,78,79]. This highlights the importance of designing education strategies focused on COVID-19 vaccination in the context of HIV infection.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the study is based on a non-probabilistic sample from a single center, which may accurately represent patients attending this specific center but may not reflect the broader population of PLHIV in Venezuela. This is despite the institution being the primary referral center for PLHIV in the country. Furthermore, the required and calculated sample size was not obtained, which restricts the statistical power to detect certain effects or differences. Secondly, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference and only provides a snapshot of challenges during a specific period of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, information was collected at different times throughout the study period, so perceptions (e.g., vaccine willingness) may have been influenced by the rapidly evolving COVID-19 pandemic. Thirdly, the limited epidemiological surveillance on HIV in Venezuela over the past decade has posed significant challenges in acquiring data regarding the COVID-19 pre-pandemic period on newly diagnosed PLHIV, adherence, and undetectability rates, making a comparative analysis infeasible. Fourthly, while there was adequate weekly ART adherence in most patients, approximately one-third were unable to undergo viral load testing. This could be explained mainly by the limited availability of testing in the public healthcare sector and high cost in the private healthcare sector [5]. Fifthly, the limited access to CD4+ lymphocyte counting in the public system, coupled with the low income of PLHIV to afford private testing, resulted in a scarcity of T-CD4+ lymphocyte count results. This scarcity hindered our ability to correlate this value with other variables. Sixthly, some medical histories were incomplete or inadequate and were supplemented with direct patient questioning, introducing potential recall bias. Seventhly, while data on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is available, the specific reasons why they preferred not to be vaccinated were not thoroughly explored. The small sample size also limits the generalizability of these results. Finally, it was not possible to accurately calculate ART interruption and missed scheduled consultations from available records due to data quality issues.

Conclusions

The disruption of HIV services during a public health crisis such as COVID-19 is an important problem for healthcare systems and policymakers to address, as it may exacerbate disparities in the HIV treatment cascade in settings with a high HIV burden or among vulnerable populations. This study found limited impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adherence to consultations and interruptions of ART refills among PLHIV at the University Hospital of Caracas, Venezuela. However, due to the limitations of this study, it is essential to conduct comprehensive, multicenter studies with larger sample sizes that include regions with less access to the continuum of care for PLHIV.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article.

Abbreviations

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- PLHIV:

-

People living with HIV

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- STDs:

-

Sexually transmitted diseases

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- TLD:

-

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, lamivudine, and dolutegravir

- NRTIs:

-

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

- NNRTIs:

-

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

References

Global HIV. & AIDS statistics — 2022 Fact sheet []. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet

MPPS OO., ONUSIDA: Tratamiento antirretroviral para personas con VIH - Guía práctica: Venezuela. In. Caracas: Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Salud de Venezuela; 2021.

Inzaule SC, Hamers RL, Doherty M, Shafer RW, Bertagnolio S, Rinke de Wit TF. Curbing the rise of HIV drug resistance in low-income and middle-income countries: the role of dolutegravir-containing regimens. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(7):e246–52.

Page KR, Doocy S, Reyna Ganteaume F, Castro JS, Spiegel P, Beyrer C. Venezuela’s public health crisis: a regional emergency. Lancet. 2019;393(10177):1254–60.

PAHO W, UNAIDS GBJOUhtchf.: Plan maestro para El Fortalecimiento De La Respuesta Al VH, La Tuberculosis Y La malaria en la República Bolivariana de Venezuela desde una perspectiva de salud pública.

LeMessurier J, Traversy G, Varsaneux O, Weekes M, Avey MT, Niragira O, Gervais R, Guyatt G, Rodin R. Risk of sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus with antiretroviral therapy, suppressed viral load and condom use: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2018;190(46):E1350–e1360.

Josephson A, Kilic T, Michler JD. Socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 in low-income countries. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5(5):557–65.

Okereke M, Ukor NA, Adebisi YA, Ogunkola IO, Favour Iyagbaye E, Adiela Owhor G, Lucero-Prisno DE. 3rd: impact of COVID-19 on access to healthcare in low- and middle-income countries: current evidence and future recommendations. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2021;36(1):13–7.

Dorward J, Khubone T, Gate K, Ngobese H, Sookrajh Y, Mkhize S, Jeewa A, Bottomley C, Lewis L, Baisley K, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on HIV care in 65 South African primary care clinics: an interrupted time series analysis. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(3):e158–65.

Rick F, Odoke W, van den Hombergh J, Benzaken AS, Avelino-Silva VI. Impact of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) on HIV testing and care provision across four continents. HIV Med. 2022;23(2):169–77.

World Health Organization %J, Geneva SW. Disruption in HIV, Hepatitis and STI services due to COVID-19. 2020.

Bain LE, Nkoke C, Noubiap JJN. UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets to end the AIDS epidemic by 2020 are not realistic: comment on can the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target be achieved? A systematic analysis of national HIV treatment cascades. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2(2):e000227.

Lin KY, Wu PY, Liu WD, Sun HY, Hsieh SM, Sheng WH, Huang YS, Hung CC, Chang SC. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination among people living with HIV during a COVID-19 outbreak. J Microbiol Immunol Infect = Wei Mian Yu Gan ran Za Zhi. 2022;55(3):535–9.

Gushchin VA, Tsyganova EV, Ogarkova DA, Adgamov RR, Shcheblyakov DV, Glukhoedova NV, Zhilenkova AS, Kolotii AG, Zaitsev RD, Logunov DY, et al. Sputnik V protection from COVID-19 in people living with HIV under antiretroviral therapy. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;46:101360.

Vergori A, Cozzi Lepri A, Cicalini S, Matusali G, Bordoni V, Lanini S, Meschi S, Iannazzo R, Mazzotta V, Colavita F, et al. Immunogenicity to COVID-19 mRNA vaccine third dose in people living with HIV. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4922.

Bieńkowski C, Skrzat-Klapaczyńska A, Firląg-Burkacka E, Horban A, Kowalska JD. The clinical effectiveness and safety of vaccinations against COVID-19 in HIV-Positive patients: data from Observational Study in Poland. Vaccines (Basel) 2023;11(3).

Sallam M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: a concise systematic review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9(2).

Shallangwa MM, Musa SS, Iwenya HC, Manirambona E, Lucero-Prisno DE. Tukur BMJP-oh: Assessment of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among people living with HIV/AIDS: a single-centered study. 2023;10.

Kabir Sulaiman S, Sale Musa M, Isma’il Tsiga-Ahmed F, Muhammad Dayyab F, Kabir Sulaiman A, Dabo B, Idris Ahmad S, Abubakar Haruna S, Abdurrahman Zubair A, Hussein A, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among people living with HIV in a low-resource setting: a multi-center study of prevalence, correlates and reasons. Vaccine. 2023;41(15):2476–84.

Dias RFG, Bento LO, Tavares C, Ranes Filho H, Silva M, Moraes LC, Freitas-Vilela AA, Moreli ML, Cardoso LPV. Epidemiological and clinical profile of HIV-infected patients from Southwestern Goias State, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2018;60:e34.

Ozdemir B, Yetkin MA, Bastug A, But A, Aslaner H, Akinci E, Bodur H. Evaluation of epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory features and mortality of 144 HIV/AIDS cases in Turkey. HIV Clin Trials. 2018;19(2):69–74.

Baqi S, Kayani N, Khan JA. Epidemiology and Clinical Profile of HIV/AIDS in Pakistan. Trop Doct. 1999;29(3):144–8.

Rodríguez García JJ. Food Security in Venezuela: from policies to facts. Front Sustainable Food Syst 2021;5.

Sahana S, Betkerur J. Profile of HIV serodiscordant couples in a tertiary care center. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85(3):347.

Waruiru W, Kim AA, Kimanga DO, Ng’ang’a J, Schwarcz S, Kimondo L, Ng’ang’a A, Umuro M, Mwangi M, Ojwang JK, et al. The Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2012: rationale, methods, description of participants, and response rates. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(Suppl 1):3–12.

Rao A, Rucinski K, Jarrett BA, Ackerman B, Wallach S, Marcus J, Adamson T, Garner A, Santos GM, Beyrer C, et al. Perceived interruptions to HIV Prevention and Treatment Services Associated with COVID-19 for Gay, Bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in 20 countries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;87(1):644–51.

Hammoud MA, Grulich A, Holt M, Maher L, Murphy D, Jin F, Bavinton B, Haire B, Ellard J, Vaccher S, et al. Substantial decline in Use of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis following introduction of COVID-19 physical distancing restrictions in Australia: results from a prospective observational study of Gay and Bisexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;86(1):22–30.

Adadi P, Kanwugu ON. Living with HIV in the time of COVID-19: a glimpse of hope. J Med Virol. 2021;93(1):59–60.

Torres TS, Hoagland B, Bezerra DRB, Garner A, Jalil EM, Coelho LE, Benedetti M, Pimenta C, Grinsztejn B, Veloso VG. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on sexual minority populations in Brazil: an analysis of Social/Racial disparities in maintaining Social Distancing and a description of sexual behavior. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(1):73–84.

Hong C, Queiroz A, Hoskin J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, associated factors and coping strategies in people living with HIV: a scoping review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2023;26(3):e26060.

Winwood JJ, Fitzgerald L, Gardiner B, Hannan K, Howard C, Mutch A. Exploring the Social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people living with HIV (PLHIV): a scoping review. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(12):4125–40.

Kessel B, Heinsohn T, Ott JJ, Wolff J, Hassenstein MJ, Lange B. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and anti-pandemic measures on tuberculosis, viral hepatitis, HIV/AIDS and malaria-A systematic review. PLOS Global Public Health. 2023;3(5):e0001018.

Prabhu S, Poongulali S, Kumarasamy N. Impact of COVID-19 on people living with HIV: a review. J Virus Eradication. 2020;6(4):100019.

Ejima K, Koizumi Y, Yamamoto N, Rosenberg M, Ludema C, Bento AI, Yoneoka D, Ichikawa S, Mizushima D, Iwami S. HIV Testing by Public Health Centers and Municipalities and New HIV cases during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;87(2):e182–7.

Chia CC, Chao CM, Lai CC. Diagnoses of syphilis and HIV infection during the COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan. Sex Transm Infect. 2021;97(4):319.

Shi L, Tang W, Hu H, Qiu T, Marley G, Liu X, Chen Y, Chen Y, Fu G. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on HIV care continuum in Jiangsu, China. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):768.

HIV Glasgow - Virtual, 5–8. October 2020. Journal of the International AIDS Society 2020;23 Suppl 7(Suppl 7):e25616.

Bell D, Hansen KS, Kiragga AN, Kambugu A, Kissa J, Mbonye AK. Predicting the Impact of COVID-19 and the Potential Impact of the Public Health Response on Disease Burden in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(3):1191–7.

Chow EPF, Ong JJ, Denham I, Fairley CK. HIV Testing and diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Melbourne, Australia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;86(4):e114–5.

Quiros-Roldan E, Magro P, Carriero C, Chiesa A, El Hamad I, Tratta E, Fazio R, Formenti B, Castelli F. Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the continuum of care in a cohort of people living with HIV followed in a single center of Northern Italy. AIDS Res Therapy. 2020;17(1):59.

Diaz MM, Cabrera DM, Gil-Zacarías M, Ramírez V, Saavedra M, Cárcamo C, Hsieh E, García PJ. Knowledge and Impact of COVID-19 on Middle-Aged and Older People living with HIV in Lima, Peru. medRxiv 2021.

Siewe Fodjo JN, Villela EFM, Van Hees S, Dos Santos TT, Vanholder P, Reyntiens P, Van den Bergh R, Colebunders R. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Medical follow-up and Psychosocial Well-Being of people living with HIV: a cross-sectional survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85(3):257–62.

Ballivian J, Alcaide ML, Cecchini D, Jones DL, Abbamonte JM, Cassetti I. Impact of COVID-19-Related stress and lockdown on Mental Health among people living with HIV in Argentina. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85(4):475–82.

Suryana K, Suharsono H, Indrayani AW, Wisma Ariani LNA, Putra WWS, Yaniswari NMD. Factors associated with anti-retroviral therapy adherence among patients living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:824062.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). and HIV: Key issues and actions [https://www.paho.org/en/news/24-3-2020-coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-and-hiv-key-issues-and-actions].

Gutiérrez-Velilla E, Piñeirúa-Menéndez A, Ávila-Ríos S, Caballero-Suárez NP. Clinical Follow-Up in people living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(8):2798–812.

Liu WD, Wang HY, Du SC, Hung CC. Impact of the initial wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan on local HIV services: Results from a cross-sectional online survey. Journal of microbiology, immunology, and infection = Wei mian yu gan ran za zhi 2022;55(6 Pt 2):1135–1143.

Pereira GFM. Brazil sustains HIV response during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(2):e65.

Celestin K, Allorant A, Virgin M, Marinho E, Francois K, Honoré JG, White C, Valles JS, Perrin G, De Kerorguen N, et al. Short-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV Care utilization, Service Delivery, and continuity of HIV Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) in Haiti. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(5):1366–72.

Siewe Fodjo JN, Faria de Moura Villela E, Van Hees S, Vanholder P, Reyntiens P, Colebunders R. Follow-Up survey of the impact of COVID-19 on people living with HIV during the second semester of the pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(9).

Hochstatter KR, Akhtar WZ, Dietz S, Pe-Romashko K, Gustafson DH, Shah DV, Krechel S, Liebert C, Miller R, El-Bassel N, et al. Potential influences of the COVID-19 pandemic on Drug Use and HIV Care among people living with HIV and Substance Use disorders: experience from a pilot mHealth intervention. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(2):354–9.

Tamargo JA, Martin HR, Diaz-Martinez J, Trepka MJ, Delgado-Enciso I, Johnson A, Mandler RN, Siminski S, Gorbach PM, Baum MK. COVID-19 testing and the impact of the pandemic on the Miami Adult studies on HIV Cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;87(4):1016–23.

Chilot D, Woldeamanuel Y, Manyazewal T. COVID-19 Burden on HIV patients attending antiretroviral therapy in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a Multicenter cross-sectional study. Res Sq 2021.

Karjadi TH, Maria S, Yunihastuti E, Widhani A, Kurniati N, Imran D. Knowledge, attitude, Behavior, and socioeconomic conditions of people living with HIV in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. HIV/AIDS (Auckland NZ). 2021;13:1045–54.

Qiao S, Li Z, Weissman S, Li X, Olatosi B, Davis C, Mansaray AB. Disparity in HIV Service Interruption in the outbreak of COVID-19 in South Carolina. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(1):49–57.

Gutiérrez-Velilla E, Piñeirúa-Menéndez A, Ávila-Ríos S, Caballero-Suárez NP. Clinical Follow-Up in people living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. AIDS Behav 2022:1–15.

Kalichman SC, Eaton LA, Berman M, Kalichman MO, Katner H, Sam SS, Caliendo AM. Intersecting pandemics: impact of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) protective behaviors on people living with HIV, Atlanta, Georgia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85(1):66–72.

Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Willig JH, Westfall AO, Ulett KB, Routman JS, Abroms S, Raper JL, Saag MS, Allison JJ. Missed visits and mortality among patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(2):248–56.

Traeger L, O’Cleirigh C, Skeer MR, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Risk factors for missed HIV primary care visits among men who have sex with men. J Behav Med. 2012;35(5):548–56.

Ahmed A, Dujaili JA, Jabeen M, Umair MM, Chuah LH, Hashmi FK, Awaisu A, Chaiyakunapruk N. Barriers and enablers for adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV/AIDS in the era of COVID-19: a qualitative study from Pakistan. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:807446.

Campbell LS, Masquillier C, Knight L, Delport A, Sematlane N, Dube LT, Wouters E. Stay-at-Home: the impact of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Household Functioning and ART Adherence for people living with HIV in three sub-districts of Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(6):1905–22.

Weinstein ER, Harkness A, Ironson G, Shrader CH, Duncan DT, Safren SA. Life Instability Associated with Lower ART Adherence and other poor HIV-Related Care outcomes in older adults with HIV. Int J Behav Med. 2023;30(3):345–55.

Times. PJ–hwpcnd-s-c-a-t-o-m-a-c–o: drug shortage concerns are top of mind amid COVID-19 outbreak. In.

Rewari BB, Mangadan-Konath N, Sharma M. Impact of COVID-19 on the global supply chain of antiretroviral drugs: a rapid survey of Indian manufacturers. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health. 2020;9(2):126–33.

Sun Y, Li H, Luo G, Meng X, Guo W, Fitzpatrick T, Ao Y, Feng A, Liang B, Zhan Y, et al. Antiretroviral treatment interruption among people living with HIV during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a nationwide cross-sectional study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(11):e25637.

Geretti AM, Stockdale AJ, Kelly SH, Cevik M, Collins S, Waters L, Villa G, Docherty A, Harrison EM, Turtle L, et al. Outcomes of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) related hospitalization among people with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) in the ISARIC World Health Organization (WHO) clinical characterization protocol (UK): a prospective observational study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(7):e2095–106.

Bhaskaran K, Rentsch CT, MacKenna B, Schultze A, Mehrkar A, Bates CJ, Eggo RM, Morton CE, Bacon SCJ, Inglesby P, et al. HIV infection and COVID-19 death: a population-based cohort analysis of UK primary care data and linked national death registrations within the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(1):e24–e32.

Tesoriero JM, Swain CE, Pierce JL, Zamboni L, Wu M, Holtgrave DR, Gonzalez CJ, Udo T, Morne JE, Hart-Malloy R, et al. COVID-19 outcomes among persons living with or without diagnosed HIV infection in New York State. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037069.

Ortiz-Martínez Y, López-López MÁ, Ruiz-González CE, Turbay-Caballero V, Sacoto DH, Caldera-Caballero M, Bravo H, Sarmiento J, Rodriguez-Morales AJ. Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination in people living with HIV/AIDS from Latin America. Int J STD AIDS, 0(0):09564624221091752.

Shrestha R, Meyer JP, Shenoi S, Khati A, Altice FL, Mistler C, Aoun-Barakat L, Virata M, Olivares M, Wickersham JA. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and Associated Factors among people with HIV in the United States: findings from a National Survey. Vaccines. 2022;10(3):424.

Su J, Jia Z, Wang X, Qin F, Chen R, Wu Y, Lu B, Lan C, Qin T, Liao Y, et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination and influencing factors among people living with HIV in Guangxi, China: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):471.

Ekstrand ML, Heylen E, Gandhi M, Steward WT, Pereira M, Srinivasan K. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among PLWH in South India: implications for Vaccination campaigns. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;88(5):421–5.

Vallée A, Fourn E, Majerholc C, Touche P, Zucman D. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among French people living with HIV. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9(4).

Liu Y, Han J, Li X, Chen D, Zhao X, Qiu Y, Zhang L, Xiao J, Li B, Zhao H. COVID-19 vaccination in people living with HIV (PLWH) in China: A Cross Sectional Study of Vaccine Hesitancy, Safety, and immunogenicity. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9(12).

Lyons N, Bhagwandeen B, Todd S, Boyce G, Samaroo-Francis W, Edwards J. Correlates and predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among persons living with HIV in Trinidad and Tobago. Cureus. 2023;15(3):e35961.

Fajar JK, Sallam M, Soegiarto G, Sugiri YJ, Anshory M, Wulandari L, Kosasih SAP, Ilmawan M, Kusnaeni K, Fikri M et al. Global prevalence and potential influencing factors of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy: a Meta-analysis. Vaccines (Basel) 2022;10(8).

Mohamed R, White TM, Lazarus JV, Salem A, Kaki R, Marrakchi W, Kheir SGM, Amer I, Ahmed FM, Khayat MA, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and associated factors among people living with HIV in the Middle East and North Africa region. South Afr J HIV Med. 2022;23(1):1391.

Tsang SJ. Predicting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Hong Kong: Vaccine knowledge, risks from coronavirus, and risks and benefits of vaccination. Vaccine: X. 2022;11:100164.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DAFP, FSCN, JLFP, NACÁ, and MEL conceived and designed the study. DAFP, DLMM, ÓDOÁ, ALM, VLV, MDMB, YC, LV, and MFA collected clinical data. DAFP, FSCN, JLFP, NACÁ, and MVMR analyzed and interpreted the data. DAFP, FSCN, JLFP, NACÁ, DLMM, ÓDOÁ, MDMB, and CMRS wrote the manuscript. FSCN, MC, JC, RNG, MCR, and MEL critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University Hospital of Caracas (CBE-HUC-17/2021). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles for medical research in humans of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Venezuelan regulations for this type of research, with the corresponding signed informed consent of all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Forero-Peña, D.A., Carrión-Nessi, F.S., Forero-Peña, J.L. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people living with HIV: a cross-sectional study in Caracas, Venezuela. BMC Infect Dis 24, 87 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08967-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08967-6