Abstract

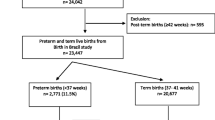

This project examines risk and protective factors for preterm birth (PTB) among Black women in Oakland, California. Women with singleton births in 2011–2017 (n = 6199) were included. Risk and protective factors for PTB and independent risk groups were identified using logistic regression and recursive partitioning. Having less than 3 prenatal care visits was associated with highest PTB risk. Hypertension (preexisting, gestational), previous PTB, and unknown Women, Infant, Children (WIC) program participation were associated with a two-fold increased risk for PTB. Maternal birth outside of the USA and participation in WIC were protective. Broad differences in rates, risks, and protective factors for PTB were observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the California Department of Public Health, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the California Department of Public Health.

References

Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Curtin SC, Arias E. Deaths: final data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2017;66(6).

Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):261–9.

Moster D, Lie RT, Markestad T. Long-term medical and social consequences of preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(3):262–73.

Räikkönen K, Pesonen A-K, Kajantie E, Heinonen K, Forsén T, Phillips DIW, et al. Length of gestation and depressive symptoms at age 60 years. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2007;190:469–74.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK. Births: final data for 2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;68(13).

Farley TA, Mason K, Rice J, Habel JD, Scribner R, Cohen DA. The relationship between the neighbourhood environment and adverse birth outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2006;20(3):188–200.

Braveman PA, Heck K, Egerter S, Marchi KS, Dominguez TP, Cubbin C, et al. The role of socioeconomic factors in black–white disparities in preterm birth. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):694–702.

Coley SL, Aronson RE. Exploring birth outcome disparities and the impact of prenatal care utilization among North Carolina teen mothers. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23(5):e287–94.

Ncube CN, Enquobahrie DA, Burke JG, Ye F, Marx J, Albert SM. Transgenerational transmission of preterm birth risk: the role of race and generational socio-economic neighborhood context. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(8):1616–26.

Moore E, Blatt K, Chen A, Van Hook J, DeFranco EA. Relationship of trimester-specific smoking patterns and risk of preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):109.e1–109.

Hibbs S, Rankin KM, David RJ, Collins JW. The relation of neighborhood income to the age-related patterns of preterm birth among white and African-American women: the effect of cigarette smoking. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(7):1432–40.

Mendez DD, Hogan VK, Culhane JF. Institutional racism, neighborhood factors, stress, and preterm birth. Ethn Health. 2014;19:479–99.

Collins JW Jr, Rankin KM, David RJ. African American women’s lifetime upward economic mobility and preterm birth: the effect of fetal programming. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(4):714–9.

Pickett KE, Collins JW, Masi CM, Wilkinson RG. The effects of racial density and income incongruity on pregnancy outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(10):2229–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.023.

University of California, San Francisco, Preterm Birth Initiative – California, retrieved from https://pretermbirthca.ucsf.edu/california-preterm-birth-initiative. Accessed 9/20/2020

Dankwa-Mullan I, Pérez-Stable EJ. Addressing health disparities is a place-based issue. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):637–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303077.

Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL, Baer RJ, Blumenfeld YJ, Ryckman KK, O'Brodovich HM, Gould JB, et al. Maternal characteristics and mid-pregnancy serum biomarkers as risk factors for subtypes of preterm birth. BJOG. 2015;122(11):1484–93.

Baer RJ, McLemore MR, Adler N, et al. Pre-pregnancy or first-trimester risk scoring to identify women at high risk of preterm birth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;231:235–40.

California Department of Public Health – Vital Records (CDPH-VR) Birth Files, 2011–2017.

Hothorn T, Hornik K, Zeileis A. Unbiased recursive partitioning: a conditional inference framework. J Comput Graph Stat. 2006;15(3):651–74.

Frisbie WP, Echevarria S, Hummer RA. Prenatal care utilization among non-Hispanic whites, African Americans, and Mexican Americans. Matern Child Health J. 2001;5(1):21–33.

Vintzileos AM, Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Scorza WE, Knuppel RA. The impact of prenatal care in the United States on preterm births in the presence and absence of antenatal high-risk conditions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(5):1254–7.

Samadi AR, Mayberry RM. Maternal hypertension and spontaneous preterm births among black women. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91(6):899–904.

Premkumar A, Henry DE, Moghadassi M, Nakagawa S, Norton ME. The interaction between maternal race/ethnicity and chronic hypertension on preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(6):787.e1–8.

Quesada O, Gotman N, Howell HB, Funai EF, Rounsaville BJ, Yonkers KA. Prenatal hazardous substance use and adverse birth outcomes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(8):1222–7.

Fingar KR, Lob SH, Dove MS, Gradziel P, Curtis MP. Reassessing the association between WIC and birth outcomes using a fetuses-at-risk approach. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(4):825–35.

Elo IT, Vang Z, Culhane JF. Variation in birth outcomes by mother’s country of birth among non-Hispanic black women in the United States. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(10):2371–81.

Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, Rubashkin N, et al. The giving voice to mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):77.

Daniels P, Noe GF, Mayberry R. Barriers to prenatal care among Black women of low socioeconomic status. Am J Health Behav. 2006;30(2):188–98.

Edmonds BT, Mogul M, Shea JA. Understanding low-income African American womenʼs expectations, Preferences, and Priorities in Prenatal Care. Fam Commun Health. 2015;38(2):149–57.

Salm Ward TC, Mazul M, Ngui EM, Bridgewater FD, Harley AE. “You learn to go last”: perceptions of prenatal care experiences among African-American women with limited incomes. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(10):1753–9.

Culhane JF, Goldenberg RL. Racial disparities in preterm birth. Semin Perinatol. 2011;35(4):234–9.

Chambers BD, Baer RJ, McLemore MR, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL. Using index of concentration at the extremes as indicators of structural racism to evaluate the association with preterm birth and infant mortality—California, 2011–2012. J Urban Health. 2019;96(2):159–70.

Rosenthal L, Lobel M. Explaining racial disparities in adverse birth outcomes: unique sources of stress for Black American women. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(6):977–83.

Giurgescu C, Zenk SN, Templin TN, Engeland CG, Kavanaugh K, Misra DP. The impact of neighborhood conditions and psychological distress on preterm birth in African-American women. Public Health Nurs. 2017;34(3):256–66.

Sumbul T, Spellen S, McLemore MR. A transdisciplinary conceptual framework of contextualized resilience for reducing adverse birth outcomes. Qual Health Res Qual Health Res. 2020;30(1):105–18.

Code Availability

Software application or custom code. Available upon request.

Funding

This research was supported by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Preterm Birth Initiative, California, funded by Marc and Lynne Benioff. The study funder has no role in any of the study activities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have participated in the study conception and design; data analysis and interpretation; critical development and revision of the article for significant intellectual content; and approval of the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

Statistical Analysis Software version 9.4 (Cary, NC) was used to analyze data received by UCSF as of March 1, 2020. Methods and protocols for the study were approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS) (project # 2019-024, approved on 2/18/2020) which serves as the institutional review board (IRB) for the California Health and Human Services Agency (CHHSA). The role of the CPHS and other IRBs is to assure that research involving human subjects is conducted ethically and with minimum risk to participants.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McLemore, M.R., Berkowitz, R.L., Oltman, S.P. et al. Risk and Protective Factors for Preterm Birth Among Black Women in Oakland, California. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 8, 1273–1280 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00889-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00889-2