Abstract

Background

In cash-for-care schemes, care users are granted a budget or given a voucher to purchase care services, under the assumption that this will enable them to become engaged and empowered customers, leading to more person-centered care. However, opponents of such schemes argue that the responsibility of organizing care is thereby shifted from governments to care users, thus reducing care users’ experience of empowerment. The tension between these opposing discourses supposes that other factors affect care users’ experience of empowerment.

Objective

This systematic review explores the experiences of empowerment and person-centered care of budget holders in cash-for-care schemes and the antecedents that can affect this experience.

Method

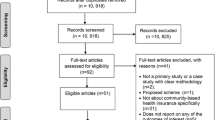

We screened seven databases up to October 10, 2022. To be included, articles needed to be peer-reviewed, written in English or French, and contain empirical evidence of the experience of empowerment of budget holders in the form of qualitative or quantitative data.

Results

The initial search identified 10,966 records of which 90 articles were retained for inclusion. The results show that several contextual and personal characteristics determine whether cash-for-care schemes increase empowerment. The identified contextual factors are establishing a culture of change, supportive financial climate, flexible regulatory framework, and access to support and information. The identified personal characteristics refer to the financial, social, and personal resources of the care user.

Conclusion

This review confirms that multiple factors can affect care users’ experience of empowerment. However, active cooperation and communication between care user and care provider are essential if policy makers wish to increase care users’ experience of empowerment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability statement

A detailed overview of the search string per database and the coding sheet can be found in the Electronic Supplementary Material. The data used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

11 May 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-023-00633-y

References

Dent M, Pahor M. Patient involvement in Europe – a comparative framework. J Health Organ Manag. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-05-2015-0078.

Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00098-8.

Da Roit B, Le Bihan B. Similar and yet so different: cash-for-care in six European countries’ long-term care policies. Milbank Q. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00601.x.

Timonen V, Convery J, Cahill S. Care revolutions in the making? A comparison of cash-for-care programmes in four European countries. Ageing Soc. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X0600479X.

Benjamin AE. Consumer-directed services at home: a new model for persons with disabilities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.80.

Crozier M, Muenchberger H, Colley J, Ehrlich C. The disability self-direction movement: Considering the benefits and challenges for an Australian response. Aust J Soc Issues. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2013.tb00293.x.

Powers LE, Sowers J-A, Singer GHS. A cross-disability analysis of person-directed, long-term services. J Disabil Policy Stud. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1177/10442073060170020301.

Kane RL, Kane RA. What older people want from long-term care, and how they can get it. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.114.

Riedel M, Kraus M, Mayer S. Organization and supply of long-term care services for the elderly: a bird’s-eye view of old and new EU Member States. Soc Policy Adm. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12170.

Ferguson I. Increasing user choice or privatizing risk? the antinomies of personalization. Br J Soc Work. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcm016.

Scourfield P. Implementing the Community Care (direct payments) Act: Will the supply of personal assistants meet the demand and at what price? J Soc Policy. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279405008871.

Prandini R. Themed section: the person-centred turn in welfare policies: bad wine in new bottles or a true social innovation? INTRODUCTION. Int Rev Sociol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2017.1422888.

Spandler H. Friend or Foe? Towards a Critical Assessment of Direct Payments. Crit Soc Policy. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018304041950.

Herbert RJ, Gagnon AJ, Rennick JE, O’Loughlin JL. A systematic review of questionnaires measuring health-related empowerment. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1891/1541-6577.23.2.107.

Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Zimmerman MA, Checkoway BN. Empowerment as a multi-level construct: perceived control at the individual, organizational and community levels. Health Educ Res. 1995. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/10.3.309.

Kodner DL. Consumer-directed services: lessons and implications for integrated systems of care. Int J Integr Care. 2003. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.80.

Webber M, Treacy S, Carr S, Clark M, Parker G. The effectiveness of personal budgets for people with mental health problems: a systematic review. J Ment Health. 2014. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2014.910642.

FitzGerald Murphy M, Kelly C. Questioning, “choice”: a multinational metasynthesis of research on directly funded home-care programs for older people. Health Soc Care Community. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12646.

Arksey H, Kemp PA. Dimensions of Choice: A narrative review of cash-for-care schemes. York: University of York, Social Policy Research Unit; 2008.

Castro EM, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W, Van Hecke A. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: A concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.026.

Spreitzer GM. Social structural characteristics of psychological empowerment. Acad Manage J. 1996. https://doi.org/10.2307/256789.

Zimmerman MA. Taking aim on empowerment research: on the distinction between individual and psychological conceptions. Am J Community Psychol. 1990. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00922695.

Zimmerman MA. Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. Am J Community Psychol. 1995. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02506983.

Woodward KF. Individual nurse empowerment: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12407.

Conger JA, Kanungo RN. The empowerment process: integrating theory and practice. Acad Manag Rev. 1988. https://doi.org/10.2307/258093.

Schulz PJ, Nakamoto K. Health literacy and patient empowerment in health communication: the importance of separating conjoined twins. Patient Educ Couns. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.09.006.

Seibert SE, Wang G, Courtright SH. Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: a meta-analytic review. J Appl Psychol. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022676.

Thomas KW, Velthouse BA. Cognitive elements of empowerment: an “Interpretive” Model of Intrinsic Task Motivation. Acad Manage Rev. 1990. https://doi.org/10.2307/258687.

Spreitzer GM. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad Manag J. 1995. https://doi.org/10.2307/256865.

Maynard MT, Gilson LL, Mathieu JE. Empowerment—fad or fab? A multilevel review of the past two decades of research. J Manag. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312438773.

Higgins T, Larson E, Schnall R. Unraveling the meaning of patient engagement: a concept analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.09.002.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G, Macaulay AC, Salsberg J, Jagosh J, et al. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

Arksey H, Baxter K. Exploring the temporal aspects of direct payments. Br J Soc Work. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcr039.

Aspinal F, Stevens M, Manthorpe J, Woolham J, Samsi K, Baxter K, et al. Safeguarding and personal budgets: the experiences of adults at risk. J Adult Prot. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAP-12-2018-0030.

Baxter K, Glendinning C. Making choices about support services: disabled adults’ and older people’s use of information. Health Soc Care Community. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00979.x.

Blyth C, Gardner A. ‘We’re not asking for anything special’: direct payments and the carers of disabled children. Disabil Soc. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590701259427.

Coyle D. Impact of person-centred thinking and personal budgets in mental health services: reporting a UK pilot. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01728.x.

Daly G, Roebuck A, Dean J, Goff F, Bollard M, Taylor C. Gaining independence: an evaluation of service users’ accounts of the individual budgets pilot. J Integr Care (Brighton). 2008. https://doi.org/10.1108/14769018200800021.

Damant J, Williams L, Wittenberg R, Ettelt S, Perkins M, Lombard D, et al. Experience of choice and control for service users and families of direct payments in residential care trailblazers. J Longterm Care. 2020. https://doi.org/10.31389/jltc.27.

Davey V. Influences of service characteristics and older people’s attributes on outcomes from direct payments. BMC Geriatr. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01943-8.

Davidson J, Baxter K, Glendinning C, Irvine A. Choosing health: Qualitative evidence from the experiences of personal health budget holders. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819613499747.

Doyle Y. Disability: use of an independent living fund in south east London and users’ views about the system of cash versus care provision. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.49.1.43.

Glendinning C, Halliwell S, Jacobs S, Rummery K, Tyrer J. Bridging the gap: using direct payments to purchase integrated care. Health Soc Care Community. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2524.2000.00244.x.

Glendinning C, Halliwell S, Jacobs S, Rummery K, Tyrer J. New kinds of care, new kinds of relationships: how purchasing services affects relationships in giving and receiving personal assistance. Health Soc Care Community. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2524.2000.00242.x.

Glick P, Clarke RE, Crivellaro C. Exploring experiences of self-directed care budgets: design implications for socio-technical interventions. Chi '22. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1145/3491102.3517697.

Griffiths CA, Ainsworth E. Personalisation: direct payments and mental illness. Int J Psychosoc Rehabil. 2014. https://doi.org/10.37200/V18I1/8077.

Hamilton LG, Mesa S, Hayward E, Price R, Bright G. ‘There’s a lot of places I’d like to go and things I’d like to do’: the daily living experiences of adults with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities during a time of personalised social care reform in the United Kingdom. Disabil Soc. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1294049.

Hamilton S, Tew J, Szymczynska P, Clewett N, Manthorpe J, Larsen J, et al. Power, choice and control: how do personal budgets affect the experiences of people with mental health problems and their relationships with social workers and other practitioners? Br J Soc Work. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcv023.

Irvine F, Wah Yeung EY, Partridge M, Simcock P. The impact of personalisation on people from Chinese backgrounds: qualitative accounts of social care experience. Health Soc Care Community. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12374.

Larsen J, Tew J, Hamilton S, Manthorpe J, Pinfold V, Szymczynska P, et al. Outcomes from personal budgets in mental health: service users’ experiences in three English local authorities. J Ment Health. 2015. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1036971.

Laybourne AH, Jepson MJ, Williamson T, Robotham D, Cyhlarova E, Williams V. Beginning to explore the experience of managing a direct payment for someone with dementia: the perspectives of suitable people and adult social care practitioners. Int J Soc Res Pract. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301214553037.

Leece J. It’s a matter of choice: making direct payments work in Staffordshire. Practice. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503150008415197.

Leece J. Paying the piper and calling the tune: power and the direct payment relationship. Br J Soc Work. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcn085.

Leece J, Peace S. Developing new understandings of independence and autonomy in the personalised relationship. Br J Soc Work. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcp105.

Maglajlic R, Brandon D, Given D. Making direct payments a choice: a report on the research findings. Disabil Soc. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590025793.

Manji K. ‘It was clear from the start that [SDS] was about a cost cutting agenda.’ Exploring disabled people’s early experiences of the introduction of Self-Directed Support in Scotland. Disabil Soc. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1498767.

McGuigan K, McDermott L, Magowan C, McCorkell G, Witherow A, Coates V. The impact of direct payments on service users requiring care and support at home. Practice. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2015.1039973.

McNeill S, Wilson G. Use of direct payments in providing care and support to children with disabilities: opportunities and concerns. Br J Soc Work. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw159.

Mitchell F. Facilitators and barriers to informed choice in self-directed support for young people with disability in transition. Health Soc Care Community. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12137.

Mitchell W, Beresford B, Brooks J, Moran N, Glendinning C. Taking on choice and control in personal care and support: the experiences of physically disabled young adults. J Soc Work. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017316644700.

Moran N, Glendinning C, Wilberforce M, Stevens M, Netten ANN, Jones K, et al. Older people’s experiences of cash-for-care schemes: evidence from the English Individual Budget pilot projects. Ageing Soc. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X12000244.

Neale J, Parkman T, Strang J. Challenges in delivering personalised support to people with multiple and complex needs: qualitative study. J Interprof Care. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1553869.

Netten A, Jones K, Knapp M, Fernandez JL, Challis D, Glendinning C, et al. Personalisation through individual budgets: does it work and for whom? Br J Soc Work. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcr159.

O’Rourke G. Older people, personalisation and self: an alternative to the consumerist paradigm in social care. Ageing Soc. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X15000124.

Pearson C. Money talks? Competing discourses in the implementation of direct payments. Crit Soc Policy. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1177/026101830002000403.

Porter T, Shakespeare T, Stockl A. Trouble in direct payment personal assistance relationships. Work Employ Soc. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170211016972.

Pozzoli F. Personalisation as vision and toolkit. A case study. Int Rev Sociol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2017.1422885.

Rabiee P, Glendinning C. Choice and control for older people using home care services: how far have council-managed personal budgets helped? Qual Ageing Older Adults. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAOA-04-2014-0007.

Rabiee P, Moran N, Glendinning C. Individual budgets: lessons from early users’ experiences. Br J Soc Work. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcm152.

Rodrigues R. Caring relationships and their role in users’ choices: a study of users of Direct Payments in England. Ageing Soc. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X19000035.

Rodrigues R, Glendinning C. Choice, competition and care—developments in English social care and the impacts on providers and older users of home care services. Soc Policy Adm. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12099.

Rummery K, Lawrence J, Russell S. Partnership and personalisation in personal care: conflicts and compromises. Soc Policy Soc. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746422000525.

Spandler H, Vick N. Opportunities for independent living using direct payments in mental health. Health Soc Care Community. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00598.x.

Stainton T, Boyce S. “I have got my life back”: users’ experience of direct payments. Disabil Soc. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759042000235299.

Stevens M, Glendinning C, Jacobs S, Moran N, Challis D, Manthorpe J, et al. Assessing the role of increasing choice in english social care services. J Soc Policy. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004727941000111X.

Turnpenny A, Rand S, Whelton B, Julie BB, Babaian J. Family carers managing personal budgets for adults with learning disabilities or autism. Br J Learn Disabil. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12348.

Welch E, Jones K, Fox D, Caiels J. Personal health budgets: a mechanism to encourage service integration? J Integr Care (Brighton). 2022. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICA-07-2021-0038.

Williams V, Porter S. The Meaning of “choice and control” for People with Intellectual Disabilities who are Planning their Social Care and Support. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil JARID. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12222.

Williams V, Simons K, Gramlich S, McBride G, Snelham N, Myers B. Paying the piper and calling the tune? The relationship between parents and direct payments for people with intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil JARID. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3148.2003.00164.x.

Woolham J, Daly G, Sparks T, Ritters K, Steils N. Do direct payments improve outcomes for older people who receive social care? Differences in outcome between people aged 75+ who have a managed personal budget or a direct payment. Ageing Soc. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X15001531.

Barr M, Duncan J, Dally K. Parent experience of the national disability insurance scheme (NDIS) for children with hearing loss in Australia. Disabil Soc. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1816906.

Day J, Thorington Taylor AC, Hunter S, Summons P, van der Riet P, Harris M, et al. Experiences of older people following the introduction of consumer-directed care to home care packages: a qualitative descriptive study. Aust J Ageing. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12553.

Devine A, Dickinson H, Rangi M, Huska M, Disney G, Yang Y, et al. “Nearly gave up on it to be honest”: utilisation of individualised budgets by people with psychosocial disability within Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme. Soc Policy Admin. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12838.

Dew A, Bulkeley K, Veitch C, Bundy A, Lincoln M, Brentnall J, et al. Carer and service providers’ experiences of individual funding models for children with a disability in rural and remote areas. Health Soc Care Community. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12032.

Fisher KR, Purcal C, Jones A, Lutz D, Robinson S, Kayess R. What place is there for shared housing with individualized disability support? Disabil Rehabil. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1615562.

Howard A, Blakemore T, Johnston L, Taylor D, Dibley R. “I’m not really sure but I hope it’s better”: early thoughts of parents and carers in a regional trial site for the Australian National Disability Insurance Scheme. Disabil Soc. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2015.1093462.

Hurley J, Donelly M, Gaetano J, Bradhurst B. The National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013: experiences of family members in a regional community in New South Wales, Australia. Res Pract Intellect. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2022.2054045.

Laragy C, Fisher KR, Purcal C, Jenkinson S. Australia’s individualised disability funding packages: when do they provide greater choice and opportunity? Asian Soc Work Policy Rev. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/aswp.12068.

Laragy C, Ottmann G. Towards a Framework for Implementing Individual Funding Based on an Australian Case Study. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2011.00283.x.

Lloyd J, Moni K, Cuskelly M, Jobling A. National disability insurance scheme: is it creating an ordinary life for adults with intellectual disability? Disabil Soc. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2021.1907548.

Loadsman JJ, Donelly M. Exploring the wellbeing of Australian families engaging with the National Disability Insurance Scheme in rural and regional areas. Disabil Soc. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1804327.

Moskos M, Isherwood L. Individualised funding and its implications for the skills and competencies required by disability support workers in Australia. Labour Ind. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2018.1534523.

Ottmann G, Laragy C, Haddon M. Experiences of disability consumer-directed care users in Australia: results from a longitudinal qualitative study. Health Soc Care Community. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00851.x.

Ottmann G, Mohebbi M. Self-directed community services for older Australians: a stepped capacity-building approach. Health Soc Care Community. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12111.

Spall P, McDonald C, Zetlin D. Fixing the system? The experience of service users of the quasi-market in disability services in Australia. Health Soc Care Community. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00529.x.

Stewart V, Slattery M, Roennfeldt H, Wheeler AJ. Partners in recovery: paving the way for the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Aust J Prim Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1071/py17136.

Tracey D, Johnston C, Papps FA, Mahmic S. How do parents acquire information to support their child with a disability and navigate individualised funding schemes? J Res Spec Educ Needs. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12390.

Wilson E, Campain R, Pollock S, Brophy L, Stratford A. Exploring the personal, programmatic and market barriers to choice in the NDIS for people with psychosocial disability. Aust J Soc Issues. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.154.

Yates S, Carey G, Malbon E, Hargrave J. “Faceless monster, secret society”: Women’s experiences navigating the administrative burden of Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme. Health Soc Care Community. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13669.

Benjamin AE, Matthias RE. Age, consumer direction, and outcomes of supportive services at home. Gerontologist. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/41.5.632.

Brown M, Harry M, Mahoney K. “It’s Like Two Roles We’re Playing”: parent perspectives on navigating self-directed service programs with adult children with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12270.

Caldwell J. Experiences of families with relatives with intellectual and developmental disabilities in a consumer-directed support program. Disabil Soc. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590701560139.

Gross JMS, Wallace L, Blue-Banning M, Summers JA, Turnbull A. Examining the experiences and decisions of parents/guardians: participant directing the supports and services of adults with significant intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Disabil Policy Stud. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207312439102.

Hagglund KJ, Clark MJ, Farmer JE, Sherman AK. A comparison of consumer-directed and agency-directed personal assistance services programmes. Disabil Rehabil. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280410001672472.

Harry ML, MacDonald L, McLuckie A, Battista C, Mahoney EK, Mahoney KJ. Long-term experiences in cash and counseling for young adults with intellectual disabilities: familial programme representative descriptions. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil JARID. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12251.

Harry ML, Mahoney KJ, Mahoney EK, Shen C. The Cash and Counseling model of self-directed long-term care: Effectiveness with young adults with disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.03.001.

Keigher SM. The limits of consumer directed care as public policy in an aging society. Can J Aging. 1999. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980800009776.

Mattson Prince J, Manley MS, Whiteneck GG. Self-managed versus agency-provided personal assistance care for individuals with high level tetraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80067-0.

San Antonio P, Simon-Rusinowitz L, Loughlin D, Eckert JK, Mahoney KJ. Case histories of six consumers and their families in cash and counseling. Health Serv Res. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00674.x.

San Antonio P, Simon-Rusinowitz L, Loughlin D, Eckert JK, Mahoney KJ, Ruben KAD. Lessons from the Arkansas cash and counseling program: How the experiences of diverse older consumers and their caregivers address family policy concerns. J Aging Soc Policy. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420903385544.

Shen C, Smyer M, Mahoney KJ, Simon-Rusinowitz L, Shinogle J, Norstrand J, et al. Consumer-directed care for beneficiaries with mental illness: lessons from New Jersey’s Cash and Counseling program. Psychiatric Serv (Washington, DC). 2008. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2008.59.11.1299.

Schore J, Foster L, Phillips B. Consumer enrollment and experiences in the cash and counseling program. Health Serv Res. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00679.x.

Spaulding-Givens J, Hughes S, Lacasse JR. Money matters: participants’ purchasing experiences in a budget authority model of self-directed care. Soc Work Ment Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2018.1555105.

Junne J. Enabling accountability: an analysis of personal budgets for disabled people. Crit Perspect Accounting. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2018.01.001.

Junne J, Huber C. The risk of users’ choice: exploring the case of direct payments in German social care. Health Risk Soc. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2014.973836.

Schmidt AE. Older persons’ views on using cash-for-care allowances at the crossroads of gender, socio-economic status and care needs in Vienna. Soc Policy Adm. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12334.

Askheim OP. Personal assistance for people with intellectual impairments: experiences and dilemmas. Disabil Soc. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759032000052897.

Katzman E, Kinsella EA, Polzer J. ‘Everything is down to the minute’: clock time, crip time and the relational work of self-managing attendant services. Disabil Soc. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1649126.

Katzman E, Mohler E, Durocher E, Kinsella EA. Occupational justice in direct-funded attendant services: Possibilities and constraints. J Occup Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2021.1942173.

Christensen K. In(ter)dependent lives. Scand J Disabil Res. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017410902830553.

Christensen K. Towards sustainable hybrid relationships in cash-for-care systems. Disabil Soc. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.654990.

Ungerson C. Whose empowerment and independence? A cross-national perspective on “cash for care” schemes. Ageing Soc. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X03001508.

Funding

This study was funded by BOF.STG.2018.0026.01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Literature search, Data analysis, Writing—original draft. PG: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. SV: Literature search, Writing—review & editing. JT: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Eva Pattyn, Paul Gemmel, Sophie Vandepitte, and Jeroen Trybou declare that they had no support from any organization for the submitted article; no financial relationships with any organization that might have an interest in the submitted work; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised to remove the irrelevant legends from Tables 3 to 6.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Pattyn, E., Gemmel, P., Vandepitte, S. et al. Do Cash-For-Care Schemes Increase Care Users’ Experience of Empowerment? A Systematic Review. Patient 16, 317–341 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-023-00624-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-023-00624-z