Abstract

This article discusses activist perceptions of the beneficial potentialities of new media for environmental campaigning as investigated in Australia, due to its high level of environmental activism and Internet usage. Drawing upon literature on communication theory, environmental politics, digital activism, and social movement theory, this study explores new media use for activism in two large Australia-wide environmental campaigns: contestation of old-growth forest logging and unconventional gas mining (fracking) development. From March to May 2017, 34 environmental activists involved in these campaigns were interviewed for this study. They shared their opinions on what it meant for them to use new media, the difficulties they encountered, but also the beneficial potentialities they identified in using these media for their activism. The study findings show that new media built significantly on more ‘traditional’ forms of activism, including stalls and non-violent street demonstrations, but also enabled extended activist outreach, enhanced engagement with supporters, and boosted campaign mobilisation. As such, despite an array of quite challenging limitations they also referred to, and to which they responded strategically, Australian environmental activists found new media highly beneficial to their activism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On 20 August 2018, young Swedish activist Greta Thunberg started a ‘Skolstrejk för Klimatet’ (‘Strike for the Climate’) endeavour in her hometown of Stockholm. Sitting alone in front of the Swedish Parliament House during school hours, Thunberg aimed to raise awareness on the escalating problems linked to a rapidly changing climate and to urge policymakers to take rapid action to address climate change (Holmberg and Alvinius 2019). Going viral on social media, Thunberg’s ‘school strike’ rapidly attracted worldwide attention. It quickly escalated into a global youth ‘save the climate’ movement called #Fridaysforfuture (FFF) (Fang 2021; Holmberg and Alvinius 2019). Millions took to the streets in their cities between 2018 and 2019 (Wahlström et al. 2019).

A powerful component of the FFF movement was new media.Footnote 1 At least one-third of the school strikers learnt about FFF through social media (Wahlström et al. 2019). Acknowledging such communication prowess, the UK Media Regulator Office of Communications (Ofcom) referred to the ‘Greta Effect’ of catalysing a sharp rise in young people using social media for activist purposes (Ofcom 2020). However, while the global resonance of Thunberg’s protest was unprecedented regarding young people’s turnouts on addressing climate issues, the FFF movement added to many existing and successful environmental protest activities where new media were also of critical importance (Fischer et al. 2023; Mavrodieva et al. 2019).

In 2003, for example, in Australia, to protect the World Heritage Styx Valley Forest (Tasmania), the Wilderness Society and Greenpeace had established a digitally enabled activist base camp in a giant Eucalyptus Regnans (Lester and Hutchins 2009).Footnote 2 The protest gained worldwide media momentum, which ultimately saved the forest (Lester and Hutchins 2009). Another Australian example was the 2014 Bentley Blockade in New South Wales (NSW). It was organised to contest and shut down unconventional gas developments in the region, which it did with new media playing a key role. In both cases, the horizontal (many-to-many communication) nature of new media communication well aligned to protest activities (Kia and Ricketts 2018).

Internationally, well-known examples of big protests heavily supported by new media include the mass uprisings of the Arab Spring, which in 2011 triggered a domino effect of mobilisations across the Middle East and North Africa, or several other notable ones, including the Black Lives Matter movement started in 2014, the #MeToo movement that spread on social media in 2017, or the #JusticeforGeorgeFloyd protests in 2022 (Baik et al. 2022; Carney 2016; Charrad and Reith 2019; Chang et al. 2022).

The outcomes of using new media for enhanced political action increasingly started to attract scholarly attention in the early 1990s (Bimber 1998; Van Aelst and Walgrave 2002). For example, it was widely argued that the interactive nature of new media fostered citizen dialogue and facilitated the formation of communities of like-minded individuals by bringing ‘together’ those sharing similar values and views (Davis and Owen 1998; Kahn and Kellner 2004).

An ‘intrinsic democratic potential’ of new media was credited to its structure that enabled ‘horizontal communication’, which gave new media users direct control of the online production and distribution of their digital information (Fuchs 2005: 2). Such user control offered a new, diverse ‘landscape for social advocacy’ and activism to address social and political issues more effectively, including environmental ones (McInroy and Beer 2020: 12; Raby et al. 2017).

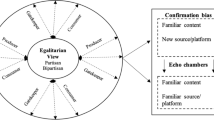

Concomitantly, and as explored elsewhere (Calibeo and Hindmarsh 2022), several limitations were also posited to challenge such beneficial potentialities. For example, there was concern around the increasing concentration of new media ownership by the few large digital corporations that owned and controlled the infrastructure of new media (e.g. Google LLC, Meta Platforms, Inc., Microsoft Corporation, and Apple, Inc.). Issues with concentration of new media ownership included potential adverse impacts on information pluralism by way of new media content filtering, information inaccessibility, and censorship (Checker 2017; Crilley and Gillespie 2018; Stasi 2020).

A recent high-profile example of such practices occurred in Australia on 18 February 2021, when Facebook prevented Australian users and news content publishers from sharing any international and national news on its social media platform (ABC News 2021). Such information blocking, which was however reversed a week later, was seen as a ‘dramatic escalation’ of a stand-off with the Australian Government’s legislation proposal requiring digital corporations to pay royalties for showing Australian news content on their platforms (ABC News 2021; Jackson 2021). Short-lasting and limited to Australia, the news ownership stoush attracted worldwide attention. Scholars, experts, and commentators reflected on the issues raised around this episode, including the opportunity proffered of diluting new media concentration, and that the Australian case would set a precedent for other countries (Bossio 2021; Roy 2021).

Other notable issues challenging the use of new media for activism included state digital surveillance of activist behaviour online in combination with traditional surveillance; superficiality of activist engagement through so-called clicktivism; and proliferation of fake news by way of social media and the formation of digital echo-chambers (Calibeo and Hindmarsh 2022; Crosby and Monaghan 2018; Fuchs 2017).

Online information overload was also signalled as a problem, due to causing social media exhaustion that also tended to constrain environmental activist calls to action (Jiang 2022; Zhang and Skoric 2020). Other scholars noted ‘contradictions and paradoxes’ characterising digital spaces for activism (McLean and Fuller 2016). For example, as noted by McLean and Fuller (2016), while new media allow multiple voices to be heard, they also are a conduit for terrorist networks to propagate their messages and recruit new members.

Although several scholarly studies explored the implications of using new media for activism and improved democracy (e.g. Bennett and Segerberg 2012; Castells 2015; Tufekci 2017), few studies focused on Australian environmental activism at the interface with new media use (Hendriks et al. 2016; Lester and Hutchins 2009; Wallis and Given 2016), less so regarding Australian activist perceptions on new media’s potentialities. In light of this scholarly equipoise about potential benefits and limitations of new media for environmental activism, it is still not clear whether new media are of value in having an impact for slowing, or reversing, environmental degradation; and if, due to the limitations, activists refrain from using new media and opt for alternatives.

On this topic, a previous study explored the impact of new media challenges and issues for Australian environmental activism; the study found that activists adopted ‘activist-responsive adaptation’ strategies to get around new media limitations (Calibeo and Hindmarsh 2022). Following up and building on such previous work, this study focuses on the perceived potentialities of new media to better understand the net benefit versus limitation of using new media for environmental activism. To do so, this study sought the first-hand opinions of Australian environmental activists as they are the direct users of new media for their campaigns. Of note in such investigation, and its contribution to the literature, is that Australia has both a high level of environmental activism and Internet usage, in international comparison (Pearse 2016; Ramshaw 2020).

Two key research questions guided the investigation: (i) what were the activist views on using new media for their campaigns? And, (ii) did the activists perceive new media as beneficial for campaigning and in providing more opportunities to protect the environment? To answer these questions, this paper first provides a background on the key potentialities of new media for activism toward achieving socio-political change, also for a better protected environment, after which are method, findings, discussion and conclusion.

Background

Potentialities of new media for environmental activism

The perceived potentialities of new media are often referred to as object ‘affordances’ (Cammaerts 2015: 87), intended as a ‘unique combination of qualities that specifies what the object affords us’ (Gibson 1977: 75). Accordingly, on new media activism, affordances refer to specific structural features that characterise these media and enable actions for environmental campaigning (Cammaerts 2015; Kent and Taylor 2021). Such affordances have been found in the loosely bounded, decentralised infrastructure of new media, characterised as ‘horizontal’ or ‘many-to-many’ communication, which can also complement vertical (one-to-many) communication structures of traditional media, including radio, TV, and newspapers (Meikle and Young 2011).

Due to their infrastructure, new media show compatibility with the loosely bounded structure of the environmental movement. This compatibility enables activists to build horizontal movements, which can be stand-alone, add to, or also use more traditionally structured, hierarchically organised campaign strategies (Checker 2017). A visual representation of the loosely bounded environmental movement was provided by Doyle and Kellow (1995: 91), as a ‘Palimpsest’ model showing how the environmental movement is the sum of interconnected structures of formal and informal groups.

As such, the environmental movement spans large environmental NGOs (ENGOs) to smaller community groups (Hidayat and Stoecker 2018). A variety of strategies lend themselves to both digital and non-digital practices. These include education programs and voluntary conservation programs and non-violent direct action, civil resistance, or disobedience activities involving social mobilisations such as rallies, strikes and blockades. Activist strategies also include petitions and other forms of political pressure and recruitment, as well as environmental conservation and protection activities (Delina and Diesendorf 2016; Doyle and Kellow 1995).

Environmental activism and the media

Environmental activists have been at the centre of deploying the abovementioned strategies, which began more readily with the formation of the environmental movement in the 1960s. The initial key engagement conduit was the mass media of television, radio, newspapers, and magazines, which aimed to better draw public attention to environmental issues. Early issues included the damming of rivers, air pollution, anthropogenic climate change, overpopulation, and deforestation (Anderson 2014; Lester and Hutchins 2009). Following on from the mass media conduit, environmental activists were early adopters of new media (Pickerill 2006; Thaler et al. 2012). As early as the mid-1980s, activist communication strategies started incorporating the Internet, including the innovative campaigning use of chat rooms and emails (Tufekci 2017).

As such, Hendriks et al. (2016: 1121) believed a key political strength of the Internet was the removal of physical constraints to engage ‘publics over vast geographical distances, or between administrative boundaries’. Similarly, McLean et al. (2019), argued that new media were a space where diverse agendas could communicate and intersect, and offered new opportunities for engagement. For activists, new media provided keen opportunity for political pressure through ‘self-representation’, a term which refers to the opportunity and ability to share activist ‘stories’ directly, without relying on traditional media interpretation (Lester and Hutchins 2012). Traditional media could be highly selective and misrepresentational, and characterised by a ‘media bias’ often influenced by various factors such as media ownership, source of income, and political orientation of the media outlet as well as its audience (Dumitrica and Felt 2020; Hamborg et al. 2019: 392).

Self-representation is also closely linked the use of ‘mediated visibility’ in many campaign places, which helps social and political struggles gain recognition in the public space through the media (Thompson 2005: 49; also, Lester and Hutchins 2012). This is because, in digital spaces, mediated visibility allows environmental activists to expose many ‘hidden’ environmental struggles. For example, by using drones to reveal deteriorating wildlife conditions, worsening pollution, illegal tree clearing, and icebergs melting due to climate change (Kelly and Patrick 2019).

In this context, the use of powerful imagery, or ‘image events’, as argued by Delicath and DeLuca (2003: 315), is key to strategically advance the visibility of environmental claims by subverting dominant mass narratives. As such, Hutchins and Lester (2015: 339) posited ‘mediatized environmental conflict’ as ‘a prominent feature of media saturated social worlds in which the communication of environmental risks, threats, and disasters is ever present’.

New media influence on activism

New media have been suggested as capable to profoundly influence activism by providing a conduit for organising new and emergent forms of collective action (Bennett and Segerberg 2012; Checker 2017; Cox and Schwarze 2015; Vaast et al. 2017). In addition to more traditional forms of collective action (such as those centrally coordinated by NGOs), new forms of collective action through new media follow a logic of ‘connective action’ (Bennett and Segerberg 2012: 743). Connective action refers to decentralised and more spontaneous ‘large scale, fluid social networks’, which form quickly through users simultaneously sharing ideas on an issue through new media (Bennett and Segerberg 2012: 748; McInroy and Beer 2020; Rosenbaum and Bouvier 2020).

Such practices allow digitally formed social networks to mobilise quickly for political action (Hyun-soo and Lim 2020; Tufekci 2017). For example, Boulianne et al. (2020) investigated a cycle of protest events held in the USA in 2017 that informed the Women’s March and the March for Science. These authors found a direct and consistent link between social media use, particularly of Twitter, and protest participation and mobilisation, and increased public awareness of the issues being raised. In contrast, the impact of using traditional media for political participation was found minimal.

Likewise, regarding the 2011 Occupy Wall Street Movement, online efforts saw rapid formations of dispersed and ‘networked counterpublics’, which facilitated face-to-face protest attendance through alternative narratives to those of mainstream media (Penney and Dadas 2014: 88). It thus seems that new media do offer new venues to catalyse mobilisation and exert stronger political pressure that can have an impact for social change (McLean et al. 2019). However, it remains unclear whether increased mobilisation and political pressure through new media can truly foster meaningful socio-political change; in other words, where do the potentialities of new media lie in relation to activism, in this case, for enhanced environmental protection?

New media practices and socio-political change

Several examples are discussed in the literature that highlight the success or failure of the use of new media for activist campaigns in relation to political outcomes they generate. A successful example is the mass e-mobilisation that followed British Petroleum’s (BP) Gulf of Mexico oil spill, which disclosed BP’s poor record of environmental and safety standards and, eventually, led to the largest corporate settlement in US history, with BP fined US$18.7 billion (Jurgens et al. 2016; Vaast et al. 2017). By contrast, an example that also saw a high usage of new media for activist operations, but did not manage to achieve long-lasting political change, was the 2014 Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong. In that case, Beijing did not make any concession on the movement’s demands for electoral reform regardless of the extent and resonance of the civic mobilisation fostered by new media (Agur 2021; Wang and Wong 2021).

On the outcomes of digitally enabled activism, Shirky (2011: 29) argued that the use of new media ‘does not have a single preordained outcome … [and] attempts to outline their effects on political action are too often reduced to dueling anecdotes’, as the examples above show. Instead of focusing on the short-term outcomes of new media use, thus, Shirky’s suggestion was to adopt an ‘environmental view’ about new media influence on the public sphere; with such view focused on the long-term political goal of strengthening civil society through societal interactions facilitated by new media.

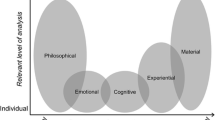

Other scholars proposed a social analysis of digital activism through a ‘multifaceted understanding’ of the diverse social contexts and circumstances in which activists adopt ‘media practices’ to achieve different goals and objectives (Belotti et al. 2022: 723; Mattoni 2020). Media practices refer to the complex interactions between media objects and individuals within social movements as part of a vast ‘repertoire of communication’ encompassing grassroots activism (Mattoni 2020: 2830).

Exploring new media use for activism through the more holistic lens of media practices, Mattoni (2020) argued, broadens the scholarly understanding of the relationship between media and activism. This is because such lens overcomes conceptualisations of technological determinism suggesting that technologies generate social consequences (also Treré and Mattoni 2016). In short, new media create ‘windows of opportunity’ for change and hold potential for influencing political outcomes, but do not determine them (Meikle 2018: 335; also Belotti et al. 2022; Treré and Mattoni 2016).

It is in this context of trying to better understand new media affordances for activists, in this case, in the context of environmental activism, that this study is located. As such, the next section illustrates the site information for the study investigation, followed by the method guiding the study.

Site information

Two areas of contestation—old-growth forest logging and unconventional gas mining using hydraulic fracturing (fracking)—have been identified as prominent in the Australian environmental activism arena and, thus, selected for this study. These campaigns have been widespread and active at both national and local (community) levels for several decades, and still are, to date, in Australia. The selection of the two campaigns provided a rich and diverse representation of the contemporary use of new media for activism, as both extensively used new media. This usage was ascertained directly with the activists contacted by phone and email before interview processes started. In the maintime, the Australian environmental activists involved in these campaigns were found to use primarily Facebook, Twitter to a lesser extent, and YouTube as new media conduits, with the larger groups all having their own websites.

On old-growth forest logging

Clearing of native forests began in Australia with European settlement in the late eighteenth century, mainly for agricultural and pastoral reasons. As indicated in the latest report on the Australia State of the Environment (2021), over the last 30 years, about 6.1 million ha of forest has been cleared in Australia, in addition to other areas of vegetation cleared for uses such as pastures, with substantial cumulative impact of natural capital loss (Cresswell et al. 2021). Accordingly, concerns on diminishing forest biodiversity, slow regrowth rates, and overall impacts on climate change emissions have been raised over time (Evans 2016; Hansen et al. 2014).

Although efforts to protect Australian forests begun in the twentieth century, targeted campaigns contesting forest logging increased from the late 1960s with the advent of the contemporary environmental movement (Hutton and Connors 1999). Campaign actions included strikes, demonstrations, blockades, fundraising events, and public awareness campaigns, which now include digital activism strategies of sharing videos and photos of logged areas, running online petitions, mediated visibility tactics, and directly targeting politicians on social media.

On hydraulic fracturing (otherwise commonly known as ‘fracking’)

In turn, the last two decades have seen rapid expansion of the fracking industry in Australia. It has seen an increasingly polarised debate between environmentalists allied to farmers and rural host communities on one side, and governments and developers on the other (Colvin et al. 2015; Hindmarsh and Alidoust 2019). Fracking contesters raise issues of water contamination, land appropriation and devaluation, impacts on human health, and greenhouse emissions of mining and their impact on global climate change (Duffy 2022; O’Neill and Schneider 2021).

Aimed at pressuring governments to consider these issues, activist mobilisation efforts include informative online and offline actions to raise community awareness, for example, through producing and disseminating movies and documentaries; but also, using new media to organise blockades and protest events as well as coordinating town hall meetings to update local communities and gather more support (Muncie 2020).

Method

The research method comprised face-to-face, in-depth interviews with 34 environmental activists. Potential respondents were selected through a desktop search of the main groups involved with the two campaigns across different scales, from local to state level. Group representatives were contacted directly on the basis of their involvement with the campaign about their availability to be interviewed. However, snowballing sampling was also adopted as potential respondents genuinely recommended other contacts to be involved (Parker et al. 2019).

Interviews

Between February and April 2017, interviews were conducted in Queensland, the Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia, and Western Australia. Of the 34 respondents, 17 held career positions in large and mainly metropolitan environmental organisations (ENGOs), and 17 represented smaller, voluntarist, and less hierarchical local community-based groups (community groups).

A semi-structured questionnaire was used to gather the activist perspectives on how they viewed and used new media for their activism, and to invite further reflection on the beneficial potentialities and limitations of new media, if any were identified. Interviews were held in various settings, depending on the respondent availability and preference: some occurred in public spaces such as cafes of libraries, others in corporate offices, and some in private locations where the activists operated or lived.

The research human ethics privacy procedures of Griffith University did not allow any details about activist or group names to be revealed.Footnote 3 Thus, in the following results, respondents are referred to by way of codes. The code ‘ENGO’ is used for ‘environmental organisations’, and ‘CG’ is used for ‘community groups’, followed by a number associated to each respondent. The interviews, which lasted about 1 h each, were recorded with the participants’ consent and transcribed for qualitative analysis on NVivo11. The latter was used to code the raw interview data through a thematic analysis based on identifying commonalities and divergences found in the data (Hsieh and Shannon 2005; Owen 1984).

Results

Interview analysis

Three key themes were identified, whereby activists perceived the most beneficial potentialities of new media for enhanced activism: ‘We became our own media!’: platforms for delivery and engagement; improved civic mobilisation; and, practical advantages.

‘We became our own media!’: platforms for delivery and engagement

First, respondents opined that new media beneficially allowed them to directly communicate about their environmental struggles and issues without often selected and misrepresentational ‘sound bite’ coverage from TV or newspapers. As respondent CG5 enthusiastically stated: ‘we became our own media!’ without being filtered by traditional media’s editorial discretion.

Self-representation, as also noted by other respondents, helped activists challenge negative stereotyping of environmental activists, such as ‘greenies’ or ‘unemployed hippy serial protesters’, by traditional media sensationalism (respondent CG8). In addition, there were important news visibility benefits. In referring to a 31-day long protest camp organised in Tasmania to protect a remote old-growth forest from logging, respondent CG7 commented: ‘With traditional media, since you are relying on a reporter showing up, and a photographer, we would have been 31 days with nobody knowing we were doing a thing.’

Second, a recurrent view among respondents was that new media were an easily adaptable means of communication that was compatible with the structure of the environmental movement, which facilitated activism. For example, respondent C13, who was involved in the anti-fracking movement, opined that new media were ‘fortunately compatible with the complex networks that environmental campaigning has traditionally worked through … There’s just a real, instant compatibility between the two’. An important element of such communication efficiency was where Respondent CG13 outlined that the environmental movement consisted of both horizontal and decentralised networks in which many new ideas ‘just arose from the many individuals inside its network’.

Improved civic mobilisation

Most respondents also commented on the raised potentialities of new media for improved overall civic mobilisation and pressure politics, both online and offline. However, some respondent opinions differed on the exact nature of such potentialities. The general argument was that while the role of new media was pivotal for effective mobilisation, the role of face-to-face communication and campaigning could not be underestimated. For example, in describing the organisation of a community campaign to stop fracking, Respondent CG13 commented that face-to-face interactions were very helpful in getting critical mass interest in the area; only once this had been achieved, new media could be highly useful to mobilise online interests quickly:

We had neighbour to neighbour [community] engagement in which every house in the region was surveyed and informed, and people signed on which was completely neighbour networking; and that created that mobilisation potential that enabled us to use social media to mobilise in the instant.

In turn, respondents expressed how difficult it was to imagine how they could now prompt mass mobilisation so quickly without social media. Respondent CG9 commented: ‘You have people that come to your community meeting saying, “oh I just saw this event that popped up on my Facebook feed” … You would have never been able to do that before.’

However, it was also noted that often, regardless of how much effort activists put into online campaigning, it was difficult to keep supporters interested over time, or ‘in touch’. Thus, Respondent CG13 opined, the realisation of the communication potentiality of new media for protecting the environment was only possible with the support of a ‘real-life social movement’ with ‘roots in the ground’. Additionally, some digital strategies did not always achieve the desired or projected outcomes as digital strategies did not always succeed in generating enough community engagement, in raising politicians’ interest around certain issues, or, ultimately, in halting logging or fracking operations from going ahead.

For example, it was difficult for online petitions to be considered for discussion in Parliament because they were often dismissed by decision-makers due to their digital nature, with the latter often positioned as a weak or irrelevant form of activism, as ‘politicians would think that those signing the petition are just fake people or fake profiles’ (ENGO16) Any setbacks, however, did not discourage the activists from continuing their online campaigning work at all, according to Respondent ENGO10, ‘just to keep working on it’.

In turn, new media were considered powerful to exert online pressure on politicians, government representatives, and corporate actors to change or improve their policies and activities regarding the environment. This was because such online targeting effectively manifested community sentiment toward environmental issues that politicians could not ignore, especially when directly called into question about them. Such tactics often targeted the electorates of politicians and companies. For example, Respondent ENGO9 commented that when environmental issues occurred in a specific electorate, such as pollution, or relaxation of land clearing laws, social media exposure would put such activities under the electoral ‘spotlight’.

Another method was through disclosing drone footage of hidden forested coupes being cleared. Such exposure aimed to then destabilise the voting base, enabling activists to create stronger leverage for change. For this reason, Respondent CG2 hoped the exposure (or mediated visibility) effect of new media would be ‘the death knell of stupid decision making, as no longer could a politician or a leader just get up and say “bullshit” and get away with it’.

Practical advantages

Lastly, most respondents (97%) mentioned practical advantages of new media. Among the most cited advantages were cost and time effectiveness. On cost effectiveness, respondent ENGO9, for example, noted it was ‘certainly cheaper to do social media than it is to put an ad on TV; those can cost 10 thousand dollars … Or to put a billboard up: again, very expensive’. In terms of time effectiveness, activist opinions converged on the benefits of being able to create, modify, and distribute new media content in a much quicker manner than through traditional media or other avenues such as face-to-face meetings.

Additionally, new media were easy to adopt and operate. Purposes included creating engaging posts and managing large databases to analytically measure the impact of campaigning activities. The latter helped in predicting and shaping campaign strategies: it was common for the respondents to use social media analytics tools to measure the impact of their actions. For example, Respondent ENGO4 commented that by repeatedly posting on Facebook ‘you see what resonates with people, what people care about, and what makes people angry… just by having them respond on Facebook. And that can shape our campaigns’.

Another advantage was that organisationally, new media were useful for accelerating decision-making and collaboration with other environmental groups, in Australia and/or internationally, without the need for long-distance travel. New media were also an invaluable asset for environmental groups operating in remote and or rural Australian locations, or for state-wide campaigns where distances are difficult to cover in person, especially in Australia. For example, respondent CG3 opined:

I think because we live in an isolated place … driving around here, we have done promotional mailboxes for our area for land care, it takes all day driving around, and it costs too much money to put it with the mailman. So, we did drive but I am not going to do it again.

Discussion

The focus of this study was on Australian environmental activists and their perceptions about using new media for their activism. The first research question was ‘what were the activist views on using new media for their campaigns?’. In relation to this question, this study shows that new media were of fundamental importance to Australian activists.

First, new media afforded the activists self-representation and mediated visibility: they offered a key communicative conduit to disclose environmental struggles that would otherwise might be unreported, or scantily or inaccurately reported by traditional media (Dumitrica and Felt 2020; Hamborg et al. 2019; Lester and Hutchins 2012). As such, the activists felt increased validation for their activism as they gained control over the content they created and shared. This is what they meant by becoming ‘their own media’: being able to provide unfiltered insights into their activist experiences on their own terms.

New media were considered central for pressure politics tactics and activist engagement with the public, which often resulted in increased mobilisation on the ground. These views also echo the findings of Boulianne et al. (2020), who found a direct link between social media use and increased civic mobilisation, and in relation to enhanced potential to engage people, especially younger generations, with environmental and conservation issues (Fischer et al. 2023).

The findings of this study also showed that the idea of compatibility between the decentralised structure of new media and the loosely bounded structure of the environmental movement was shared by the activists (Doyle and Kellow 1995). This resonates with Tufekci’s argument (2014: 16), about new media enabling ‘horizontal’ protests with activists detaching themselves from traditionally centralised activities in favour of increased networked action. This finding also aligns with Checker’s (2017) views about the weak ties characterising networking activities on social media, which allow individuals to override political or cultural divergences to work toward a common goal.

However, the activists also recognised that several limitations challenged the beneficial potentialities of new media for activism and, accordingly, had some concerns about how to best use these media for activist purposes. For example, they commented that the widely adopted strategy of online petitions was often dismissed by politicians simply because of their digital nature, which eventually weakened petitions’ impact on issue resolution.

Another perceived limitation of new media was that they would not replace face-to-face, grassroots interaction, with the latter described as underpinning effective campaigning and central to building successful online activities. The logic of decentralised ‘connective action’ of shared ideas simultaneously through new media could then be better realised (Bennett and Segerberg 2012). In the Australian context, these and other limitations have been discussed by Calibeo and Hindmarsh (2022). In their study, digital echo-chambers, dissemination of fake news leading to misinformation, trolling and abusive online behaviours, and information overload were highlighted among the most mentioned issues identified as disruptors for communication, ultimately negatively impacting on activism.

The second research question was: ‘Did the activists perceive new media as beneficial for campaigning and in providing more opportunities to protect the environment?’ Following on the previous research question, the study findings showed that activists perceived new media as holding strong potentialities, as well as some limitations, to contribute to a protected environment through enhanced, more supported, and better connected forms of activism. Regardless of the limitations, activists did not refrain from using new media for their campaigns and, instead, strategically deployed them whenever possible and adaptively responded to the limitations (Calibeo and Hindmarsh 2022).

As argued by Belotti et al. (2022), it is through this digital learning-by-doing approach that activists figure out and negotiate what new media affordances best apply to their circumstances and act accordingly to identify the most appropriate political use of such media. In this sense, as argued by Mattoni (2020) in a study on how new media intersect with activist practices and engagement, new media are more than just a tool for activist communication: they encompass grassroots activism at the interface of mediatisation, traditional media, and non-mediated (face-to-face) communication (Mattoni 2020; McLean et al. 2019).

As such, if we were to establish if new media are definitely able to improve activism on the basis of the long-term outcomes they produced, then any failure to change Australian policies, or operations, of tree-logging and fracking would point to a failure of new media to foster environmental change in Australia. However, the campaigns considered here—well supported by digital resources—though not always able to realise immediate environmental outcomes, have been effective in strongly building on short-term goals of mobilisation and raising issue awareness.

The effectiveness of new media was also perceived by Australian environmental activists to contribute positively towards creating social and environmental change for the longer-term (see also, Checker 2017; Mattoni 2020; Shirky 2011); but, of course, time will tell. These Australian findings, accordingly, contribute to the international literature that new media provides a more effective infrastructure for activist mobilisation and creating opportunities for positive environmental change (Checker 2017; Meikle 2018; Tufekci 2017).

Conclusions

The adoption of new media as a pervasive means of communication is associated with organising and strategizing for activism in new and transformative ways, according to Australian environmental activists involved in two large and enduring Australia-wide environmental campaigns, those of old-growth logging and unconventional gas mining through fracking. Such viewpoints were the results offered from this study on investigating how Australian activists perceived the use of new media to increase their abilities to improve environmental protection.

Despite some constraining issues related to using new media for activism, Australian activists perceived important potentialities of new media. Key ones included extending campaign outreach, increasing public awareness of environmental problems, and improving activist mobilisation for both online and offline activities. These benefits added to practical advantages of new media for communication and campaigning especially in rural areas of Australian regions where campaigns contesting fracking and forest-logging were also highly active, in addition to many others in rural areas like industrial agriculture, land erosion, diminishing species diversity, bushfires, floods, and those also happening in many urban and coastal areas. In conclusion, this study contributes Australian understandings to the international debate around using new media for environmental activism by providing the point of view of those (the activists) directly involved in such uses, or, as they say, at the ‘coal-face’.

Nevertheless, this study has some limitations. For example, further investigation could explore how, in Australia, the new media landscape has evolved since the interviews were conducted (in 2017), and the implications of such change on activist perceptions about new media use for their campaigns, as well as the social impacts of COVID-19 on digital environmental activism, in Australia and elsewhere.

Another limitation of the study is that it only focuses on the perspectives of a sample of activists involved in contesting fracking and old-growth forest logging in Australia. Research opportunity and deeper understanding lies in extending the sample group to those, for example, concerned with nuclear energy, climate justice, or Indigenous rights. Such lines of research could also be furthered internationally to compare with Australian views. Overall, to more deeply explore the potentials of new media to contribute to a more sustainable future.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed in the current study can be found in the Griffith University Repository: https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3319. Individual interview transcripts cannot be published or shared as that would be in violation of the ethical clearance guidelines of Griffith University.

Notes

The giant gum tree, or mountain ash (Eucalyptus Regnans), of Victoria and Tasmania, is one of the largest species and attains a height of about 90 m (300 feet) and a circumference of 7.5 m (24.5 feet)’ (Encyclopædia Britannica 2023).

References

ABC News (2021) Facebook news ban stops Australians from sharing or viewing Australian and international news content. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-02-18/facebook-to-restrict-sharing-or-viewing-news-in-australia/13166208. Accessed 13 January 2023

Agur C (2021) Hong Kong and the Umbrella Movement: mobile social media, activism, and social change. In: Subramanian R, Felsberger S (eds) Mobile Technology and Social Transformations: Access to Knowledge in Global Contexts. Routledge, New York, pp 125–135

Ahmed Y, Ahmad M, Ahmad N, Zakaria N (2018) Social media for knowledge sharing: a systematic literature review. Telematics Inform 37:1–17

Anderson A (2014) Media, Environment and the Network Society. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Baik J, Nyein T, Modrek S (2022) Social media activism and convergence in tweet topics after the initial #MeToo Movement for two distinct groups of Twitter users. J Interpers Violence 37:13603–13622

Belotti F, Donato S, Bussoletti A, Comunello F (2022) Youth activism for climate on and beyond social media: insights from FridaysForFuture-Rome. Int J Press/politics 27:718–737

Bennett W, Segerberg A (2012) The logic of connective action: digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Inf Commun Soc 15:739–768

Bimber B (1998) The Internet and political transformation: populism, community, and accelerated pluralism. Polity 31:133–160

Bossio D (2021) Facebook has pulled the trigger on news content - and possibly shot itself in the foot. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/facebook-has-pulled-the-trigger-on-news-content-and-possibly-shot-itself-in-the-foot-155547 Accessed 29 August 2022

Boulianne S, Koc-Michalska K, Bimber B (2020) Mobilizing media: comparing TV and social media effects on protest mobilization. Inf Commun Soc 23:642–664

Calibeo D, Hindmarsh R (2022) From Fake News to Echo-Chambers: On The Limitations of New Media for Environmental Activism in Australia, and “Activist-Responsive Adaptation”. Environmental Communication 16:490–504

Cammaerts B (2015) Social media and activism. In: Mansell R, Hwa P (eds) The International Encyclopaedia of Digital Communication and Society. Wiley-Blackwell, New York, pp 1027–1034

Carney N (2016) All Lives Matter, but so does race: Black Lives Matter and the evolving role of social media. Humanit Soc 40:180–199

Castells M (2015) Networks of outrage and hope: social movements in the Internet age. Polity Press, Cambridge

Chang H-CH, Richardson A, Ferrara E (2022) #JusticeforGeorgeFloyd: how Instagram facilitated the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. PLoS ONE 17:e0277864

Charrad M, Reith N (2019) Local solidarities: how the Arab Spring protests started. Sociol Forum 34:1174–1196

Checker M (2017) Stop FEMA now: social media, activism, and the sacrificed citizen. Geoforum 79:124–133

Colvin M, Witt B, Lacey J (2015) Strange bedfellows or an aligning of values? Exploration of stakeholder values in an alliance of concerned citizens against coal seam gas mining. Land Use Policy 42:392–399

Cox R, Schwarze S (2015) The Media/Communication Strategies of Environmental Pressure Groups and NGOs. In: Cox R, Hansen A (eds) The Routledge Handbook of Environment and Communication. Routledge, New York, pp 73–85

Cresswell I, Janke T, Johnston E (2021) Australia State of the Environment 2021: overview. Independent report to the Australian Government Minister for the Environment, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

Crilley R, Gillespie M (2018) What to do about social media? Politics, populism and journalism. Journalism 20:173–176

Crosby A, Monaghan J (2018) Policing Indigenous movements. Fernwood Publishing, Winnipeg

Davis R, Owen D (1998) New media and American politics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Delicath J, DeLuca K (2003) Image events, the public sphere, and argumentative practice: the case of radical environmental groups. Argumentation 17:315–333

Delina L, Diesendorf M (2016) Strengthening the climate action movement: strategies from contemporary social action campaigns. Interface: J about Soc Movements 8:117–141

Doyle T, Kellow J (1995) Environmental politics and policy making in Australia. MacMillan, Melbourne

Duffy R (2022) Synecdoche and battles over the meaning of ‘fracking.’ Environ Commun 16:339–351

Dumitrica D, Felt M (2020) Mediated grassroots collective action: negotiating barriers of digital activism. Inf Commun Soc 1:1–17

Encyclopædia Britannica (2023) Australian mountain ash. https://www.britannica.com/plant/Australian-mountain-ash. Accessed 15 Feb 2023

Evans M (2016) Deforestation in Australia: drivers, trends and policy responses. Pac Conserv Biol 22:130–150

Fang C (2021) The case for environmental advocacy. J Environ Stud Sci 11:169–172

Fischer F, Bernard M, Kemppinen K, Gerber L (2023) Conservation awareness through social media. J Environ Stud Sci 13:23–30

Fuchs C (2005) The Internet as a self-organizing socio-technical system. Cybern Human Knowing 11:57–81

Fuchs C (2017) Social media: a critical introduction. Sage, London

Gibson J (1977) The theory of affordances. In: Shaw R, Bransford J (eds) Perceiving, acting, and knowing: Toward an ecological psychology. Routledge, Hillsdale, pp 67–82

Hamborg F, Donnay K, Gipp B (2019) Automated identification of media bias in news articles: an interdisciplinary literature review. Int J Digit Libr 20:391–345

Hansen E, Panwar R, Vlosky R (2014) In the global forest sector: changes, practices, and prospects. CRC Press, London

Hendriks C, Duus S, Ercan S (2016) Performing politics on social media: the dramaturgy of an environmental controversy on Facebook. Environ Polit 25:1102–1125

Hidayat D, Stoecker R (2018) Community-based organizations and environmentalism: how much impact can small, community-based organizations working on environmental issues have? J Environ Stud Sci 8:395–406

Hindmarsh R, Alidoust S (2019) Rethinking Australian CSG transitions in participatory contexts of local social conflict, community engagement, and shifts towards cleaner energy. Energy Policy 132:272–282

Holmberg A, Alvinius A (2019) Children’s protest in relation to the climate emergency: a qualitative study on a new form of resistance promoting political and social change. Childhood 27:78–92

Hsieh H-F, Shannon S (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15:1277–1288

Hutchins B, Lester L (2015) Theorizing the enactment of mediatized environmental conflict. Int Commun Gaz 77:37–358

Hutton D, Connors L (1999) History of the Australian environment movement. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hyun-soo K, Lim C (2020) From virtual space to public space: the role of online political activism in protest participation during the Arab Spring. Int J Comp Sociol 60:409–434

Jackson W (2021) Australian news sites reappear on Facebook after government agrees to amend media bargaining laws. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-02-26/australian-news-sites-reappear-on-facebook-media-laws/13195100 Accessed 10 August 2022

Jiang S (2022) The roles of worry, social media information overload, and social media fatigue in hindering health fact-checking. Soc Media + Soc 8:1–12

Jurgens M, Berthons P, Edelman L, Pitt L (2016) Social media revolutions: the influence of secondary stakeholders. Bus Horiz 59:129–136

Kahn R, Kellner D (2004) New media and internet activism: from the ‘Battle of Seattle’ to blogging’. New Media Soc 6:87–95

Kelly D, Patrick P (2019) The use of drones in environmental compliance. Nat Resour Environ 33:59–63

Kent M, Taylor M (2021) Fostering dialogic engagement: toward an architecture of social media for social change. Soc Media + Soc 1:1–10

Kia A, Ricketts A (2018) Enabling emergence: the Bentley Blockade and the struggle for a gasfield free Northern Rivers. Southern Cross Univ Law Rev 1:49–74

Lester L, Hutchins B (2009) Power games: environmental protest, news media and the internet. Media Cult Soc 31:579–595

Lester L, Hutchins B (2012) The power of the unseen: environmental conflict, the media and invisibility. Media Cult Soc 34:847–863

Mattoni A (2020) A Media-in-Practices approach to investigate the nexus between digital media and activists’ daily political engagement. Int J Commun 14:2828–2845

Mavrodieva A, Rachman O, Harahap V, Shaw R (2019) Role of social media as a soft power tool in raising public awareness and engagement in addressing climate change. Climate 7:1–15

McInroy L, Beer O (2020) Wands up! Internet-mediated social advocacy organizations and youth-oriented connective action. New Media Soc 1:1–17

McLean J, Fuller S (2016) Action with(out) activism: understanding digital climate change action. Int J Sociol Soc Policy 36:578–595

McLean J, Maalsen S, Prebble S (2019) A feminist perspective on digital geographies: activism, affect and emotion, and gendered human-technology relations in Australia. Gend Place Cult 26:740–761

Meikle G (ed) (2018) The Routledge companion to media and activism, 1st edn. Routledge, New York

Meikle G, Young S (2011) Media convergence: networked digital media in everyday life. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Muncie E (2020) ‘Peaceful protesters’ and ‘dangerous criminals’: the framing and reframing of anti-fracking activists in the UK. Soc Mov Stud 19:464–481

O’Neill B, Schneider M (2021) A public health frame for fracking? Predicting public support for hydraulic fracturing. Sociol Q 62:439–463

Ofcom (2020) Parents more concerned about their children online. Ofcom. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/about-ofcom/latest/features-and-news/parents-more-concerned-about-their-children-online. Accessed 25 June 2022

Owen W (1984) Interpretive themes in relational communication. Quart J Speech 70:274–287

Parker C, Scott S, Geddes A (2019) Snowball sampling. In: Atkinson P, Delamont S, Cernat A, Sakshaug J, Williams R (eds) SAGE Research Methods Foundations. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Pearse R (2016) Moving targets: carbon pricing, energy markets, and social movements in Australia. Environ Polit 25:1079–1101

Penney J, Dadas C (2014) (Re)Tweeting in the service of protest: digital composition and circulation in the Occupy Wall Street movement. New Media Soc 16:74–90

Pickerill J (2006) Radical politics on the net. Parliam Aff 59:266–282

Raby R, Caron C, Théwissen-LeBlanc S, Prioletta J, Mitchell C (2017) Vlogging on YouTube: the online, political engagement of young Canadians advocating for social change. J Youth Stud 21:495–512

Ramshaw (2020) Social media statistics for Australia 2020. Genroe. https://www.genroe.com/blog/social-media-statistics-australia/13492. Accessed 30 September 2022.

Rosenbaum J, Bouvier G (2020) Twitter, social movements and the logic of connective action: Activism in the 21st century – an introduction. Participations 17:120–125

Roy J (2021) Facebook vs. Australia – Canadian media could be the next target for ban. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/facebook-vs-australia-canadian-media-could-be-the-next-target-for-ban-155728. Accessed 23 February 2022.

Shirky C (2011) The political power of social media: technology, the public sphere, and political change. Foreign Aff 90:28–41

Siapera E (2018) Understanding new media. Sage, London

Stasi M (2020) Ensuring pluralism in social media markets: some suggestions. Research Paper No. RSCAS 2020/05. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, Florence

Thaler A, Zelnio K, MacPherson R, Shiffman D, Bik H, Goldstein M, McClain C (2012) Digital environmentalism: tools and strategies for the evolving online ecosystem. In: Gallagher D (ed) Environmental Leadership: A Reference Handbook. Sage, London, pp 229–236

Thompson J (2005) The new visibility. Theory Cult Soc 22:31–51

Treré E, Mattoni A (2016) Media ecologies and protest movements: main perspectives and key lessons. Inf Commun Soc 19:290–306

Tufekci Z (2014) Social movements and governments in the digital age: evaluating a complex landscape. J Int Aff 68:1–18

Tufekci Z (2017) Twitter and tear gas: the power and fragility of networked protest. Yale University Press, New Haven

Vaast E, Safadi H, Lapointe L, Negoita B (2017) Social media affordances for connective action: an examination of microblogging use during the Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill. Manag Inf Syst Q 41:1179–1205

Van Aelst P, Walgrave S (2002) New media, new movements? The role of the internet in shaping the ‘anti-globalization’ movement. Inf Commun Soc 5:465–493

Wahlström M, Kocyba P, De Vydt M, de Moor J (2019) Protest for a future: composition, mobilization and motives of the participants in Fridays For Future climate protests on 15 March, 2019 in 13 European cities. https://eprints.keele.ac.uk/6571/7/20190709_Protest%20for%20a%20future_GCS%20Descriptive%20Report.pdf. Accessed 21 March 2023

Wallis J, Given L (2016) #Digitalactivism: new media and political protest. First Monday 21:1–12

Wang Y, Wong H (2021) Electoral impacts of a failed uprising: evidence from Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement. Elect Stud 71:1–12

Zhang N, Skoric M (2020) Getting their voice heard: Chinese environmental NGO’s Weibo activity and information sharing. Environ Commun 14:844–858

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Richard Hindmarsh and Leah Burns for comments on an earlier draft, and the comments of the anonymous reviewers.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. The author has no financial or non-financial interests in any material discussed in this article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Calibeo, D.L. “We became our own media!” : Australian perspectives on the beneficial potentialities of new media for environmental activism. J Environ Stud Sci 14, 213–223 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-023-00885-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-023-00885-y