Abstract

Cross-national survey data shows that for a significant share of European citizens, corruption is acceptable. Notwithstanding the importance of prior knowledge on corruption extension and experience, research has made little progress in exploring why people condone it, especially in unsuspicious countries, with effective institutions and stable democratic rules and processes. The present study examines this gap in the literature by assessing the European Values Study (EVS) and the Special Eurobarometer (EB) attempts at measuring ‘Tolerance towards Corruption’ (TtC) in OECD countries in Europe during the same period (2017–2019). In the end, measurements proved to be constrained by the limited number of questions/items that try to capture TtC, which gave room to conclude that: (a) EVS and EB approaches do not measure the same TtC. The first measures it through social transgressions not exclusively related to corruption, while the second measures the willingness to accept a public-office corruption when dealing with the public sphere. (b) Lower ages combined with individual preferences/perceptions of less satisfaction with life, widespread corruption, and prior experiences with corruption proved to be more relevant to explain TtC, regardless of the country in which individuals were surveyed. (c) The type of TtC citizens display in advanced democracies proved to be mainly contingent on their age and on the way they interpret the extension of corruption and the prior contact they had with a public-office corruption in a given society.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Research on corruption has traditionally treated people’s unawareness and unreadiness to take a proactive role in the prevention of and the fight against corruption as a problem of less developed societies with fragile institutions. This leads us to believe that even what the most important international anticorruption statutes declare is not targeted to advanced democraciesFootnote 1: “substantially reduce corruption and bribery in all their forms” (target 16.5 of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development) and “participation should be strengthened by […] undertaking public information activities that contribute to nontolerance of corruption” (article 13 of the United Nations Convention against Corruption).

However, evidence shows that this is far from being the case. Unsuspicious countries, with effective institutions and stable democratic rules and processes, have also to struggle with citizens’ indifference and permissiveness towards corruption. A significant share of citizens in Europe—nearly 30% (European Commission, 2017, p. 14)—tolerate corruption. These people disapprove the way the fight against corruption has been conducted at the national level; whereas they accept at a great extent that not reporting a case of corruption is justifiable when ‘everybody knows about these cases’ or because ‘no one wants to betray anyone’ (European Commission, 2017, p. 98, 2018a, p. 73). These results not only entail a clear dysfunction at the core of advanced democracies, but they also help us to raise a series of pertinent questions about ‘Tolerance towards Corruption’ (TtC) in those environments: (1) What do the available TtC indicators in fact represent and measure? (2) What factors prove to be important to determine TtC? (3) What types of individuals condone corruption and why?

The concept of TtC, understood here as the willingness to accept or endure behaviors that are judged as deviant from the ethical standards or expectations governing offices of entrusted authority,Footnote 2 needs to be better entrenched. In the absence of an in-depth debate (Malmberg, 2019, p. 11), the concept seems to have been divided into two: one that says it is tolerance “citizens’ support for corrupt politicians” (Pozsgai-Alvarez, 2015, p. 102) and other that says it is “the extent to which individuals tend to justify practices that are widely considered corrupt” (Moreno, 2002).

Adding complexity to all this, cross-country operationalization is scarce and not ‘made-to-measure’, what made these different conceptualizations receive also different names—‘tolerance’, ‘permissiveness’ or ‘acceptance’—while using basically the same measurements expressed in terms of individual perceptions regarding everyday situations or conducts expected to govern public–private interactions that may be seen as corrupt.

TtC has received marginal importance when large-n public opinion surveys have been developed. Even though corruption has been assumed to make citizens less satisfied with the way democracies operate (Gouvêa Maciel & de Sousa, 2018), the patterns that affect the decision to condone corruption in democracies are still to be systematized. This is why the current study was carried out:

-

Since citizens need to assume a proactive role in the fight against corruption, more knowledge on TtC turns to be fundamental before implementing costly anticorruption policies with contested effectiveness and detrimental effects on democracy (Andersson & Heywood, 2009);

-

Europe is, at the same time, a region where democratic values, procedures, and institutions are largely consolidated and regularly scrutinized; and where the overall disapproval of corruption in normative terms coexists with an acceptance of corruption in practical/strategic terms (Becquart-Leclercq, 1984; de Sousa & Triães, 2008; Kaufmann & Vicente, 2011). This makes Europe an adjusted case study to explore more fluid perceptions of what may constitute corruption or not;

-

There is a lack of information on the adequacy of the existing cross-country measurements available in the region: the European Values Study (EVS) and, since 2014, the Special Eurobarometer on Corruption (EB). There was a temporal window of opportunity to put these approaches to the test together for the very first time, which appeared as a great way to advance our knowledge on how to better operationalize TtC;

-

When it comes to the factors that drive TtC, there is also much to explore. Political ideology, radicalism, life satisfaction, corruption extension, and corruption experience were used together for the first time as explanatory at the individual-level. At the country-level, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, press freedom, and political participation of younger citizens and women in parliaments were tested together with exclusivity in Europe again for the first time;

-

There was room to go a step further by designing a novel TtC typology based on the combination of individual-level variables that were found relevant after running regressions on EB data (the only measurement approach that has questions on the most traditional ways of measuring corruption—through extension and experience). This grouped information can be of relevance for the development of more refined TtC measurements to be applied in the future.

The article is structured to answer the three questions previously raised about TtC. However, before getting to the heart of the matter, the state of the art was presented to evidence that knowledge on TtC is not consolidated yet. Then, we take a closer look at those questions to understand their effective contribution to the ‘puzzle’ of TtC inside advanced democracies. In sum, they stress that: existing cross-country measurements have been used and created with no guarantees that they are comparable; explanations for TtC must go beyond sociodemographic conditions; and a typology is of value to better measure and explain nuances of TtC in democratic environments.

Next, all methodological issues are discussed: (a) the universe of analysis, sample, and data collection period—2017 EVS (2019) and EB no. 470 (European Commission, 2018b) data on 20 (n = 39,905) and 23 (n = 23,949) OECD members from Europe, respectively, and implemented almost simultaneously from 2017 to 2019—; (b) the operationalization of the dependent variable (TtC) and all individual and country-level explanatory variables; (c) the econometric model design used—logistic multilevel regressions with random-effects—; and (d) the additional technique applied to form types of TtC—K-means nonhierarchical cluster procedure.

Results and discussion are presented together to confirm TtC as a transversal phenomenon in Europe whose cross-country measurement needs to be improved. EVS and EB methodologies proved neither to operationalize TtC the same way nor to fully translate the theory behind this concept into similar representations: being TtC a mere norm violation in the first case and a ‘citizen–public sphere’ transaction in which particularistic interests are allowed to emerge in the second case. Lower ages, less satisfaction with life, widespread perceptions of corruption, and prior experiences with corruption appeared as central to describe TtC in the European context, irrespective of country-level factors that have been usually associated with corruption. Ultimately, age and the way citizens interpret these ‘extension of’ and ‘prior experience with’ a public-office corruption were sufficient elements to explain different types of TtC.

2 State of the Art

The tolerance issue has been presented as fundamental to capture the very nature of corruption (Heidenheimer, 1970), though few attempts to effectively assess it could be found up to now. At the national level, TtC has been measured basically through real-world scenarios inside specific democratic countries worldwide (Dolan et al., 1988; Gardiner, 1970; Gibbons, 1989; ICAC, 2003, 2006; Jackson & Smith, 1996; Johnston, 1986; Ko et al. 2012; Mancuso et al. 2006; Navot & Beeri, 2018) and specifically in Europe (Allen & Birch, 2012; Andersson, 2002; de Sousa & Triães, 2008; Erlingsson & Kristinsson, 2019; Johnston, 1991; Tavits, 2010). These studies presented high levels of definition/measurement detail with limited cross-national validation. In other words, they developed in-depth descriptions but gave no transversal answers to how TtC happens throughout different democracies. In the end, they provide a great analysis of ‘their own color palette used’ with no comparison to the others’ ‘palettes’.

At the cross-country-level, research experiences quite the opposite dilemma: high levels of comparability combined with very limited access to questions that deal with TtC in a straightforward way. Perception-based surveys dedicated exclusively to corruption (or at least with a set of questions about corruption and integrity) are recurrent and focus primarily on the extension (‘How widespread?’) and/or reported experience (‘Have you accepted or know someone who accepted something to…?’)(Wysmułek, 2019). Vignettes or hypothetical situations to assess TtC are scarce.Footnote 3 Outside Europe, efforts to reproduce a more detailed description of cross-country gradients of corruption tolerance could be found only in the third round of the Afrobarometer (2005).Footnote 4

When it comes to effective comparison, studies have adopted mainly few available items (everyday situations to be characterized as justifiable or not, such as ‘avoiding a fare on public transport’ or ‘someone accepting a bribe in the course of their duties’) from the World Values Survey/European Values Study (WVS/EVS) as a proxy for TtC (Catterberg & Moreno, 2005; Gatti et al., 2003; Keller & Sik, 2009; Lavena, 2013; Malmberg, 2019; Moreno, 2002; Pisor & Gurven, 2015; Pop, 2012) or opted for other pre-existent questions that could somehow represent it (Chang & Huang, 2016; Chang & Kerr, 2017), with particular reference to the EB approach, i.e. the Index of Tolerance to Corruption composed of three conducts related to public–private interactions that may be seen as corrupt (if it is acceptable to give money, to give a gift, or to do a favor to get something from the public administration or a public service) created by the European Commission (2014).

As expected, research regarding TtC in Europe has been then limited and determined by the existing measurements too. While the traditional WVS/EVS measurement approach was adopted by Pop (2012); the EB approach was used only by Hunady (2017). Being each measurement approach used in isolation, there is still no guarantee that they measure the same.

In relation to determinants, they are still to be explored, especially in European democracies. Moreno (2002) and Malmberg (2019) presented both a broader picture of tolerance which included Europe, but their focus was not on internal limitations or possible constraints democracies might have been facing because of the existence of significant levels of corruption tolerance, they both highlighted the ‘low-to-high’ variance in TtC instead. Keller and Sik (2009) were the first to stress the importance of distinguishing between active and passive forms of TtC and to explore the relation among perception, tolerance, and practice of corruption inside Europe but provided no information on TtC determinants. Pop (2012) and Hunady (2017) went a bit further. They assessed TtC exclusively in the European context searching for explanatory ‘usual suspects’ and found few similar sociodemographic determinants, contradictory moderating effects caused by the spread of a systemic corruption at the country-level and presented only an ‘one-fits-all’ typology of tolerant citizens. In addition, Hunady (2017) stressed the importance of dealing together with the experience of corruption and with its tolerance and provided initial evidence that they present a positive relation. This author also included a measure of corruption extension at the country-level to find a preliminary relation between more TtC and more corruption extension. Furthermore, corruption extension and experience were never put together to explain TtC at the individual-level in democratic contexts.

Regarding typologies, to the best of my knowledge, no study explored TtC. Only the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) of the Transparency International was evaluated in terms of clusters at the country-level (Budsaratragoon & Jitmaneeroj, 2020; Buscema et al., 2016; Waheeduzzaman, 2005). Individual-level data (especially EB variables that measure corruption extension and experience) is available but not used until now to understand how relevant factors interact to result in different expressions of TtC inside democracies.

As shown, knowledge on TtC measurements, determinants, and types in Europe is scarce, limited, and sparse. This paper aims to fill this particular gap of systematization by putting EVS and EB approaches to the test simultaneously. However, why would it be important to explore this puzzle? To ensure that the available tolerance measurements are representative of the concept (or at least dimensions of it) they aim to measure; to integrate measurement, causes, and types of TtC into the existing contemporary research on corruption in democratic environments (Doorenspleet, 2019); and to insert TtC into a multilevel analytical model of corruption, where individual, contextual, and group processes (Modesto & Pilati, 2020) together interact to describe the nuances of this phenomenon in Europe. All this is intended to provide anticorruption bodies and survey developers with more evidence about the importance of considering the corruption tolerance issue when framing policies. In a nutshell, it is not sufficient to identify whether there is too much or too little corruption in advanced democracies, it is also necessary to understand the conditions under which people decide or not that corruption is tolerable.

3 Research Questions Explained

3.1 What do the Available TtC Indicators in Fact Represent and Measure? (Q1)

There is a straightforward logic behind this question: to understand what the EVS and the EB approaches effectively operationalize when using situations or conducts to label as TtC. This is in line with what the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) proclaimed in its Users' Guide to Measuring Corruption (June et al., 2008, p. 3), which says “no single data source or tool will offer a definitive measurement” and “to put it plainly, there is little value in a measurement if it does not tell us what needs to be fixed”.

The idea is to interpret the way TtC has been operationalized by each approach through the lenses of the results from both surveys. EVS data has been used to measure TtC since Moreno’s (2002) work and remains being used with few criticism until today. Even others that apply different operationalizations do not develop an argument in favor of the measure created or/and highlight limitations found in the EVS approach (Chang & Huang, 2016; Chang & Kerr, 2017; Guo & Tu, 2017; Hunady, 2017; Ko et al., 2012; Pozsgai-Alvarez, 2014, 2015; Sautu, 2002). Malmberg (2019, p. 117) was the first to shed some light on the unrestricted adoption of the EVS approach, indicating that if we disregard the ‘accepting a bribe in the course of their duties’ item of the EVS TtC proxy, the other items “are not considered to be acts of corruption in the strict modern sense of the word”.

Measurements have been used and created with no guarantees that they are comparable. And if we are not sure about what we are measuring, the less certain we will be about what determines it, especially in advanced democracies (where less illicit forms of corruption arise). A simultaneous look at the approaches becomes necessary to justify the choice between one of them, thus avoiding the measurement of the phenomenon by mere repetition in the future.

3.2 What Factors Prove to be Important to Determine TtC? (Q2)

The work here is more fundamental than creating hypotheses about the relationship between TtC and any explanatory factor: it is to understand whether what has been pointed out as relevant to explain TtC in advanced democracies depends on the measurement approach used or not. For this reason, the aim is to assess not only the most traditional sociodemographic conditions previously tested—with particular emphasis given to ‘age’, which has always been described as a powerful explanatory factor worldwide (Gatti et al., 2003; Lavena, 2013; Malmberg, 2019) and inside Europe (Hunady, 2017; Pop, 2012; Torgler & Valev, 2006)—but also less explored personal preferences and perceptions and country-level factors (that go beyond the use of the CPI) that can deepen our knowledge on the subject.

There are two particularly important relationships that can offer elucidative answers to Q2 and are of interest for research in the field: how do the extent and experience of corruption interact together with TtC in advanced democracies? By doing this, this article aims to connect the study of TtC with a broader knowledge previously acquired on the impact of corruption on democracy (Doorenspleet, 2019; Kubbe, 2018).

3.3 What Types of Individuals Condone Corruption and Why? (Q3)

Traditional regressions can show explanatory relations effectively, but they are not suitable for describing how these relations are grouped. To learn that TtC is affected by specific factors is crucial, since it offers us the possibility to further explore different patterns and interactions among TtC and those factors—with particular attention given to the circumstances in which age influences the willingness to justify corruption (Torgler & Valev, 2006). A TtC typology can shed light on how to (and to whom) address survey questions/items about TtC and related topics and provide detailed information of interest for more effective anticorruption policymaking.

Furthermore, searching for multiple (and alternative) paths to motivate TtC is also a way to understand the ethical (and individual) decision-making behind the corrupt act itself. More knowledge on types of TtC can help us to deconstruct the myth that only ‘a few bad apples spoil the barrel’, i.e. that there is only one prototypical profile of ‘bad’ individuals inclined to condone corruption in a given society (Mulyana et al., 2019).

In the end, TtC types are expected to provide large-n evidence for what has been proclaimed by normative, experimental, and political studies: that corruption can be committed by people who do not classify their acts as corrupt (Darley, 2005, pp. 1182–1183) and that corruption tolerance can be seen as an expression of both corruption extension (how frequent it is) (Bicchieri & Xiao, 2009; Köbis et al., 2015; Mann et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2019) and experience (how close to it) (Chang & Kerr, 2017; Hunady, 2017).

4 Methodological Issues

4.1 Universe of Analysis, Sample, and Data Collection Period

Two large-n surveys conducted in Europe were considered for the purposes of this exploratory exercise. To compare measurement approaches, all the 20 OECD advanced democracies that took part in the EVS 2017 round (2019) and the 23 OECD democracies found in the EB no. 470 (European Commission, 2018b) were used to perform the statistical models. Table 1 presents the description of the universe of advanced democracies studied by measurement approach and the corresponding amount of available observations.

These survey rounds were conducted almost at the same time: between 2017 and 2019. There was even temporal overlap in fieldwork for Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Sweden. Such serendipity reduced the impact of the occurrence of critical socioeconomic events between the execution of these surveys in each country, making possible to compare them.Footnote 5

4.2 The Dependent Variable, TtC

Two tentative measurements of TtC were replicated using updated survey data. The first approach (Pop, 2012) considered as tolerant to corruption individuals who classified at least one of four corruption-related situations found in the Religion and morale module of the EVS 2017 (2019) as justifiable to some degree. The second approach (Hunady, 2017) considered as tolerant to corruption who said that at least one of three specific misconducts used to frame the Index of Tolerance to Corruption of the EB no. 470 (European Commission, 2018b) was somehow acceptable in order to get something from the public administration or a public service (Table 2).

4.3 Explanatory Variables

TtC was explained by a series of sociodemographic characteristics and preferences/perceptions presented by previous studies on TtC as of relevance (Hunady, 2017; Pop, 2012; Torgler & Valev, 2006) that appeared simultaneously in both surveys at the individual-level, as well as by a series of selected country-level macroconditions usually linked to the existing knowledge on corruption (Doorenspleet, 2019; Kubbe, 2018; Pop, 2012). Information on corruption extension and experience was available only at the EB dataset but these variables were crucial to better explore how the two most usual ways of measuring corruption in public opinion surveys (Wysmułek, 2019) interact directly with TtC. Data harmonization was applied to make surveys comparable and resulted in the use of the following variablesFootnote 6:

Individual-level variables:

(a) Sociodemographic conditions:

-

Age (in years);

-

Education (age when stopped full-time education);

-

Employment status (0 = unemployed vs. 1 = employed);

-

Gender (0 = woman vs. 1 = man).

(b) Preferences/perceptions:

-

Preferences in terms of political ideology (from 0 = left-wing to 10 = right-wing);

-

Radicalism (0 = moderate vs. 1 = radical);

-

Perceptions of life satisfaction (from 1 = not at all satisfied to 4 = very satisfied);

-

Corruption extension (from 1 = there is no corruption to 5 = corruption is very widespread);

-

Corruption experience (0 = I don’t know people who took bribes vs. 1 = I know people who took bribes).

Country-level variables:

-

The 2018 Corruption Perception Index (CPI)Footnote 7 in an inverted and logarithmic scale, chosen as a proxy for the average level of corruption in a given society (Transparency International, 2018) (ranging from 0 = no corruption to 100 = widespread corruption);

-

The 2018 GDP per capita (World Bank, 2019) based on purchasing power parity, chosen to approach the economic dimension;

-

Inequality, measured through the 2018 Gini Index (Eurostat, 2020) (ranging from 0 = perfect equality, where everyone has the same income, to 100 = full inequality, where only one person has all the income);

-

Press freedom, represented by the inverted 2018 World Press Freedom Index (Reporters sans frontières, 2020) (ranging from 0 = very serious situation to 100 = good situation);

-

Participation of young citizens in national parliaments (MPs 45 years of age or younger), measured in percentual terms of MPs elected (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2020a) until May 2020;

-

Participation of women in national parliaments, measured in percentual terms of MPs elected until May 2020 (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2020b).Footnote 8

4.4 Econometric Model Design

A multilevel econometric strategy was chosen because of the nature of the dependent variable (TtC), which has been assumed to be influenced not only by individual but also by sociocultural contexts (Malmberg, 2019; Pop, 2012). Thus, it is reasonable to accept that individuals within the same country express their perceptions of TtC in a correlated manner. Panel logistic regressions with random-effects based on the Stata/SE 12.0 command xtlogit were used with ‘individuals’ (lower level of analysis) being nested in ‘countries’ (higher level).

As said by Mingo and Faggiano (2020, p. 830), “this […] leads to hypothesize that the variability […] can depend on both the people characteristics and the different contexts in which they live [and] for this reason, a multilevel approach was deemed more appropriate”. This approach was “designed to analyze variables from different levels simultaneously, using a statistical model that properly includes the various dependencies” (Hox, 2002, p. 6) and offers the possibility of identifying the proportion of the total variance contributed by each level of analysis (individuals or countries).

Both EVS and EB models are presented in three versions each: (1) one considering sociodemographic conditions only; (2) other adding individual preferences/perceptions; and (3) another adding country-level variables. Equations 1, 2, and 3 summarize and simplify the math behind the econometric structure adopted in all multilevel models used.

where \(f\left( {^{'} TtC_{{ij}} ^{'} } \right)\) is the transformed logit of TtC declared by the individual i in country j. \({\beta }_{0j}\) is the individual-level intercept; \({\beta }_{1\mathrm{j}}\) represents the effects of all individual-level variables \(^{^{\prime}} {\text{IND}}^{^{\prime}}\) to be tested at the lower level, and \({e}_{ij}\) is the respective residual error (Eq. 1). Equation 2 predicts the average TtC in a class (the intercept \({\beta }_{0j}\)) by country-level variables \({^{'}}CNT{^{'}}\). Equation 3 describes that the relationship (as expressed by the slope coefficient \({\beta }_{1j}\)) between TtC and \({^{'}}IN{D}^{{^{'}}}\) is contingent on \({^{'}}CNT{^{'}}\). \({\mathrm{u}}_{0\mathrm{j}}\) and \({\mathrm{u}}_{1\mathrm{j}}\) are residual error terms at the higher level.

4.5 A Strategy to Form TtC Clusters using EB Individual-level Data

Additional cluster analysis, i.e. the exploratory process of “finding groups in data” (Kaufman & Rousseeuw, 1990, p. 1) was performed to further investigate the interactions between TtC and the measurements of corruption regularly used in public surveys: corruption extension and corruption experience (Wysmułek, 2019). EB measurement approach was used for this purpose, since it was the only to present these two corruption measurements in the form of objective variables.Footnote 9 In addition to this, only the individual-level variables that emerged as relevant (and statistically significant at least at the 5% level) to determine TtC from the EB regression models run (age, employment status, political radicalism, and life satisfaction) were used to create significant clusters. These variables were recoded as binary to meet Jaccard’s dissimilarity measure data standardization requirements (Jobson, 1992, pp. 503–508).Footnote 10

All citizens that classified corruption as tolerable (n = 5,520) were taken into consideration. K-means nonhierarchical procedure was used, being it suitable for exploratory data mining (Wu, 2012) and binary variable operationalization. The higher value of the Calinski-Harabasz pseudo-F Index stopping rule was obtained when three groups were set. The decision on this specific number of clusters was made to assure statistical adjustment objectivity and to provide an easy interpretation of the groups formed (Cohen, 1990).

This method provides interesting insights into how TtC can vary (and be expressed in different forms) inside advanced democracies and—even considering the existing limitations in its measurement (reduced number of EB variables available in the survey and inexistence of possibility to test corruption extension and experience with the current EVS data)—it is also valid to detect nuances in the dataset to refine and better calibrate future TtC measurements.

5 Results and Discussion

5.1 Comparing Measurement Approaches

Existing measures of TtC do not measure the same when TtC is calculated at the country-level.Footnote 11 In fact, TtC emerged as a transversal phenomenon in Europe for all countries, regardless of measurement approach used. The maps (Figs. 1 and 2) display that TtC appears to be much more widespread throughout European democracies when the EVS data is considered. 65.18% is the EVS country average of tolerant citizens, while 31.65% is the EB average. This great variation between operationalizations (EVS TtC country scores are 32.85% higher on average) is due to differences in defining gradients of corruption through survey items. Attention must be given to what should be considered ‘corrupt behavior’ prior to any subsequent explanation.

Source: EVS (2019)

TtC from the EVS perspective,

Source: European Commision (2018b)

TtC from the EB perspective,

EVS TtC measures tolerance towards social transgressions. It focuses on cheating and deception, meaning that it is based on norm violation. Corruption implies a norm violation (e.g. bribery) which needs to be regular, sanctionable, and institutionalized, but a social transgression is not necessarily corruption (Morris et al., 2015, p. 3). From the EVS perspective, no country presents less than 50% of EVS TtC, which is higher than one should expect from democratic environments, especially if it is assumed that no one is in favor of corruption (de Sousa, 2008, p. 10). In this case, all four situations used to classify corruption tolerance (claiming benefits you are not entitled to, cheating on tax, accepting a bribe, and avoiding a transport fare) entail responsibility, which follows the most elementary quality of a rule of conduct: “that action is capable of being taken by reference to it [and] you can only obey a rule when you are a responsible actor” (Alldridge, 1990, p. 10). However, EVS TtC is mixing bribery with other conducts in which the public sector or offices of entrusted authority are completely absent. This leads us to conclude that EVS TtC resembles more a measurement of social victimization per se than of corruption tolerance.

Indeed, the tendency towards victimization, i.e. acting in order to find successive acceptable excuses to justify a behavior, can shed some light on this. Perceptions of ‘self-responsibility’ regarding the decision to condone or not ordinary misconducts are directly related to ‘life as usual’ and there is empathy when judging others through your own excuses. If there is compassion for norm violation—because ‘everybody does it’, because of the noble intentions that may exist to justify it, or even because it may be wrong but still good for the whole (de Sousa, 2008, pp. 11–14)—, TtC emerges as the direct consequence of the natural functioning of democracy. The EVS approach portraits then democracies in Europe as ‘democracies without choice’, being them tinged with corruption from the inside, i.e. citizens largely tolerate it, thus societies incorporate it into their sociopolitical routines.

On the other hand, the EB approach represents how citizens in fact deal with the predisposition to accept or not corruption in ordinary transactions with the public sphere. The extensive focus on public administration makes this approach, albeit relevant, still very similar to the traditional debate on public-office-centered corruption definition, omitting a series of conducts in the private life and sector that may be considered corrupt (Pozsgai-Alvarez, 2020). EB TtC results were lower on average (but still alarming).

EB TtC does not follow the ‘north–south divide’ tendency when dissecting European data (Transparency International, 2020a), which is puzzling. Some of the preconceived ‘socioeconomic cases of success’ in the region describe remarkably similar EB TtC outputs when compared to ‘more fragile economies’: Nordic and Iberian—Finish (13.60%), Portuguese (15.60%), Swedish (17.10%), and Spanish (17.54%)—proportions of such public-office EB TtC are the lowest and significant.

5.2 Discussing Determinants

Table 3 summarizes what proved to be of relevance to determine TtC. In agreement with previous studies (Hunady, 2017; Pop, 2012; Torgler & Valev, 2006), ‘age’ appeared as the strongest explanatory sociodemographic condition for TtC, irrespective of whether considering it a social transgression (EVS models) or a breach of confidence/integrity in the public–private relationship regarding public service delivery (EB models). This relation kept valid in all EVS and EB models, even controlling for individual preferences/perceptions and country-level factors.

Other relations were contingent on the measurement approach used. When emphasis was put to measure TtC in terms of a pure social transgression, male individuals with higher formal education were more willing to justify corruption (all EVS models). On the other hand, when the focus was on citizens transactions with the public sphere, less educated unemployed tended to tolerate more corruption regardless of gender but only when interacting with individual preferences/perceptions and country-level factors (EB models 2 and 3).

Indeed, data became more revealing when preferences/perceptions were added. Citizens with right-wing ideology and propensity to radicalism (irrespective of political ideology) appeared as less prone to justify corruption in national contexts where corruption has been voiced by a free press as a matter of populist discourse (‘them’ ‘corrupt politics’ versus ‘us’ the ‘virtuous people’) only in an EVS social transgression perspective. These results are in line with what Rohac et al. (2017) recently found: that the share of votes for right-wing authoritarian populist parties in European democracies are associated with a populist discourse that uses anticorruption as a valid mechanism to weaken trust in democratic political institutions. To put it in other words, corruption has been normalized and seen as intrinsic to democracy, which constitute per se an argument to find radicalism and anti-system discourses an option to punish existing ordinary corruption. Freedom of the press became also an important factor to fuel such demagogic view of democracy, being its relationship with TtC in all EVS models reinforcing the idea that media channels “amplify the visibility of this kind of discourses” (Salgado, 2019, p. 53).

Radicalism from both sides (left and right) became significant in all models. Radical behaviors in political terms determined radical reactions against the acceptance of corruption. Since democracy has been portraited as ‘failing to deliver’ in terms of satisfaction with its operation in the region (Gouvêa Maciel & de Sousa, 2018), it was not a surprise that populist discourses connected well with the ‘corruption is not tolerable’ label.

Previous studies found that where corruption is perceived to be widespread and/or people are likelier to experience it more, less subjective well-being is expected (Tavits, 2008; Tay et al., 2014). The same held true for TtC, meaning that lesser satisfaction with life determined a higher probability of condoning corruption, which is somehow contrary to common sense: that you condone corruption more easily if you are satisfied with life.

An important add-on to the explanation was that the more corruption was perceived individually as widespread and experienced, the higher the TtC based on citizens’ transactions with the public sphere (EB models). These findings deconstruct the idea that in European democracies contexts of widespread corruption have been driving the acceptance of corruption. Indeed, victims of corruption that perceive individually it as widespread were determinant to describe the predisposition to TtC, regardless of CPI country score. This expands Chang and Kerr’s (2017, p. 10) argument “that victims of corruption [in Africa] actually tend to tolerate corruption”—and ratifies Hunady’s (2017) preliminary findings related to the fact that more perceived corruption extension and experience create room for more TtC inside Europe. Furthermore, it can be argued that—since only European OECD countries took part in the current study—an advanced democratic environment did not prove to be sufficient to prevent TtC from being significantly and simultaneously affected by the perception of corruption as widespread and previously experienced in the past (though to a lesser extent than in less democratic societies).

Contrary to Pop (2012) and Malmberg (2019), social inequality presented no statistical adjustment at the country-level. Other factors, such as higher CPI scores, greater freedom of the press, and lower shares of young MPs mattered together to determine EVS social transgression TtC; whilst the lower the participation of women in parliament, the higher the probability a citizen had to condone EB public sphere TtC. Overall, it can be said that political representation somehow affected the decision to tolerate corruption in all country-level models. The effects of living in a wealthier country on TtC were not consistent across models too.

Thus, the individual decision to justify or not corruption in European democracies could be largely explained by individual-level factors (on average, 92.03% of the total multilevel variance in all models was due to the individual-level of analysis). However, it does not mean that country-level factors were irrelevant. Albeit not directly responsible for the direct determination of TtC, their effects (of 7.97% of the total variance) were crucial to show the contribution of ‘culture’—as proposed by Moreno (2002)—in determining TtC, which was significant but lower than the contribution of individual-level factors regardless of the country in which the individuals were surveyed.

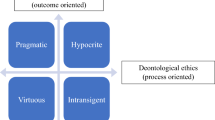

5.3 Presenting a Typology

Six variables that proved to be significant at the 5% level in the EB models presented in Subsection 5.2 (Table 3) to determine TtC at the individual-level (age, employment status, political radicalism, life satisfaction, corruption extension, and corruption experience) were grouped by mean proximity (K-means clustering) and resulted in three different profiles of TtC in advanced democracies. The interactions among those six factors appear as a valid tool to interpret what types of individuals condone corruption and what kind of relation they have especially with the most traditional ways to measure corruption in public opinion surveys. Figure 3 describes the profiles of the three types of citizens who tolerate corruption to be detailed as follows.

-

Cluster 1: ‘Empowered youth’ TtC. In this group, citizens are younger (aged up to 45 rating averaged 98.70%), preferably employed (70.84%), largely moderate in political terms (15.81%), satisfied with life (85.23%), perceive corruption as a widespread phenomenon (76.33%), and have significant experience with situations of corruption in close contacts (22.81%). Complementing Torgler and Valev’s (2006) age effect on the justifiability of bribery in selected European democracies, youth described more tolerance towards this public sphere corruption not when—or because—they get unemployed. Surprisingly, in terms of age, the higher the integration in the labour market, the more you ‘understand the rules of the game’, i.e. the necessity to justify corruption in order to succed.

-

Cluster 2: ‘Corruption blindness’ TtC. Citizens are older (100%), partially employed (44.84%), preferably moderate in political terms (13%), extremely satisfied with life (97.16%), while simply do not perceive corruption as widespread (0%) and describes little contact with experiences of corruption (10.01%). Prior experience with corruption becomes a real issue concerning older people who accept corruption in public office relations in two different ways. Cluster 2 describes the first one, in which older citizens tend to justify corruption in public dealings—albeit acting corruptly to benefit directly—when they had lower contact with corruption in the past. They still believe corruption is neither a natural condition of democracy nor an institutionalized behavior, meaning that corruption remains deviant for them.

-

Cluster 3: ‘Pulling strings’ TtC. Citizens are older (100%), partially employed (39.94%), mainly moderate in political terms (19.12%), preferably satisfied with life (77.29%), whilst presenting very high perception of corruption as widespread (99.25%), and describing more experience with corruption in close contacts compared with the other clusters (26.46%). This group represents the second way older citizens justify corruption, meaning that higher levels of experience with corruption in close relations make them see corruption almost everywhere. From this viewpoint, corruption becomes then a matter of democratic routine only (Lessig, 2012, 2013; Philp, 1997).

Source: European Commision (2018b)

TtC Typology,

EB public sphere TtC reported in OECD countries in Europe was associated basically with ‘Empowered youth’ (41.94%) or with ‘Pulling strings’ (45.94%) types, i.e. TtC in those advanced democracies was presented as an age divide, confirming Torgler and Valev’s (2006) assumption using EVS data to explore this specific relation. However, more important than focusing on age was to look at what EB data offered in terms of novelty. Corruption extension and experience proved to create another divide: between those who condone corruption because perceived it as widespread and experienced it regardless of age (87.88%) and those with ‘Corruption blindness’ (12.12%), whose TtC was a matter of their own deviant particularistic behaviors used to gain access to services and benefits, albeit refusing to accept these behaviors as corruption, which they are. This last group contradicts the general pattern previously found that lower levels of satisfaction with life means higher levels of TtC (see Table 3). For this small group (but proportionally significant in the population), if there were benefits in the corruption they committed, then it was consequently justifiable and not corruption—which seems to be a version of the ‘loss aversion’ argument used to explain corruption inside organizations (Darley, 2005, pp. 1187–1189).

6 Conclusion

The main conclusion drawn from this study is that TtC is a relevant and significant phenomenon in European democracies; however, the two measurements available in the literature are actually measuring different things. On the one hand, the EVS approach operationalizes TtC as tolerance towards social transgressions, resembling more a measurement of social victimization per se than of corruption tolerance. It is difficult to argue in favor of its adequacy in terms of effective measurement of types (Alatas, 1990; Heidenheimer et al., 1989) and political/institutional aspects of corruption (Lessig, 2012, 2013; Thompson, 1995, 2013). On the other hand, EB TtC measures how citizens deal with the predisposition to accept or not corruption in ordinary transactions with the public sphere and captures the willingness to condone a more public-office corruption only, but still omitting a series of conducts in the private life and sector that may be corruption in a contemporary perspective (Lessig, 2013; Pozsgai-Alvarez, 2020).

In relation to determinants, the main lesson learned was that TtC is a behavior framed by the relationship between individuals and the group to which they belong. Though country-level effects on TtC appeared as relevant, the analysis carried out found they explained only 7.97% of the total variance of all TtC models on average (the impact of the social environment on individual is lower than expected). Thus, lower ages combined with individual preferences/perceptions of less satisfaction with life, widespread corruption, and prior experiences with corruption proved to be more relevant to explain TtC, regardless of the country in which individuals were surveyed.

Else, grouped data on TtC revealed that the decision to condone corruption in advanced democracies is more complex than expected. The willingness to tolerate corruption proved to be mainly contingent on the age you have and on the way you interpret the extension of corruption and the prior contact you had with public-office corruption in a given society. In sum, TtC appeared as the resulting perception of the way you internalize the benefits you obtain from the corrupt act depending on the age you have.

The following practical implications resulted from this exercise. (a) Future operationalizations of TtC should take advantage of the adoption of more traditional public-office situations of corruption (such as the EB TtC and the ‘bribery item’ of the EVS TtC); however, they should consider adding other corrupt situations that are closer to what advanced democracies have been experiencing, such as influence peddling, political financing informality, and policy capture (Gouvêa Maciel & de Sousa, 2018). (b) It is important to have questions on corruption extension and experience when developing survey questionnaires to better understand how they affect TtC. By doing so, surveys could offer relevant information on how to improve anticorruption policies. (c) It is also necessary to have in mind that TtC was divided into three distinct types, which means that anticorruption policies can also take advantage of the following: measures to mitigate TtC in advanced democracies should have different approaches depending on the age and on the perceptions of life satisfaction, and corruption extension and experience of the group to which the policy was designed.

Two limitations of the current study need to be clear. First, the reduced number of explanatory variables that deal with democracy and other political issues (caused by the inexistence of items in the surveys used or the incompatibility between some EVS and EB variables) may reduce the power of the results. Second, the binary nature of the TtC operationalization implemented (which was used to facilitate the comparison of the results with previous works and also between EVS and EB measurement approaches) may limit the interpretation of data used.

As next steps for the research on TtC, five paths are suggested. (a) To explore how to develop cross-country real-world situations/scenarios of TtC considering previous knowledge on the topic provided by national surveys (Allen & Birch, 2012; Andersson, 2002; de Sousa & Triães, 2008; Erlingsson & Kristinsson, 2019; Johnston, 1991; Tavits, 2010) to improve future TtC measurements. (b) To test if TtC differs when the political actors (MPs, public officials, mayors, etc.) are surveyed. (c) To perceive with more attention the effects of social norms on TtC, since they are still to be explained (Köbis et al., 2018). (d) To see how TtC and ‘democracy-oriented’ questions on corruption—e.g. “Corruption is part of the daily functioning of democracy” (de Sousa et al., 2020)—correlate. (e) Finally, it is necessary to go the other way too and try to find what are the consequences of TtC.

Notes

Well-established electoral democracies that are members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

The Global Corruption Barometer (Transparency International, 2020b) and other traditional barometers—such as the Latinobarómetro (Corporación Latinobarómetro, 2018), the Eurobarometer (European Commission, 2020), the Asian Barometer Survey (National Taiwan University, 2016), the Arab Barometer (Arab Barometer Research Network, 2020), and the New Russia/Europe/Baltic Barometers (CSPP, 2014)—used no scenarios/vignettes/situations to explore corruption tolerance in detail.

It was an exploratory attempt to measure a public-office-centered corruption tolerance in Africa. This question did not appear in subsequent survey rounds.

EVS data for Portugal was not considered since it was collected in 2020 under the auspices of the spread of the Covid-19 disease throughout the world.

Electronic Supplementary Material Tables S1 and S2 describe in detail how each explanatory variable at the individual and at the country-level was operationalized. Table S1 also presents the process of data harmonization between surveys used.

CPI was chosen because of its simultaneous academic and practical relevance (Bello y Villarino, 2021). It has been used on a regular basis by the media and governments to present the issue of corruption in comparative terms and to justify the adoption of anticorruption measures respectively.

These two last variables were based on lower chambers or unicameral electoral results and on 2020 information, which refers to the percentage of elected (young people or women) during the last national election in each country before May 2020. This decision was made to prevent the existence of outdated electoral percentages from harming the comparison with other variables.

The EVS 2017 dataset provided no traditional measurements of perceived corruption in its standard questionnaire. To perform a cluster analysis with no dedicated corruption measurement would be thus limiting as its results could not dialogue directly with a large amount of studies that relied exclusively on public opinion surveys to assess corruption this way in Europe (Wysmułek, 2019, p. 2604).

See Electronic Supplementary Material Table S1.

TtC at the country-level is based on the proportion of tolerant citizens in relation to the total amount of citizens surveyed in each country.

References

Afrobarometer. (2005). Selected Round 3 Questionnaires. https://www.afrobarometer.org/surveys-and-methods/questionnaires. Accessed 5 June 2020.

Alatas, S. H. (1990). Corruption: Its nature, causes, and functions. Aldershot, UK: Avebury.

Alldridge, P. (1990). Rules for courts and rules for citizens. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 10(4), 487–504. https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/10.4.487

Allen, N., & Birch, S. (2012). On either side of a moat? Elite and mass attitudes towards right and wrong. European Journal of Political Research, 51(1), 89–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.01992.x

Andersson, S. (2002). Corruption in Sweden exploring danger zones and change. PhD Thesis. Umeå, Sweden: Department of Political Science, Umeå University.

Andersson, S., & Heywood, P. M. (2009). Anti-corruption as a risk to democracy: On the unintended consequences of international anti-corruption campaigns. In L. de Sousa, P. Larmour, & B. Hindess (Eds.), Governments, NGOs and anti-corruption: The new integrity warriors. (pp. 33–50). London, UK: Routledge.

Arab Barometer Research Network. (2020). Arab Barometer. https://www.arabbarometer.org/. Accessed 5 June 2020.

Becquart-Leclercq, J. (1984). Paradoxes de la corruption politique. Pouvoirs, Revue Française D’études Constitutionnelles et Politiques, 31, 19–36.

Bello y Villarino, J. M. (2021). Measuring corruption: A critical analysis of the existing datasets and their suitability for diachronic transnational research. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02657-z

Bicchieri, C., & Xiao, E. (2009). Do the right thing: but only if others do so. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 22(2), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.621

Budsaratragoon, P., & Jitmaneeroj, B. (2020). A critique on the corruption perceptions index: An interdisciplinary approach. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 70(100768), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2019.100768

Buscema, M., Sacco, P. L., & Ferilli, G. (2016). Multidimensional similarities at a global scale: An approach to mapping open society orientations. Social Indicators Research, 128(3), 1239–1258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1077-4

Catterberg, G., & Moreno, A. (2005). The individual bases of political trust: Trends in new and established democracies. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 18(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edh081

Chang, E. C. C., & Huang, S.-H. (2016). Corruption experience, corruption tolerance, and institutional trust in East Asian democracies. Taiwan Journal of Democracy, 12(1), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2014.11.031

Chang, E. C. C., & Kerr, N. N. (2017). An insider-outsider theory of popular tolerance for corrupt politicians. Governance, 30(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12193

Cohen, J. (1990). Things I have learned (so far). American Psychologist, 45(12), 1304–1312. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.45.12.1304

Corporación Latinobarómetro. (2018). Latinobarómetro. http://www.latinobarometro.org/lat.jsp. Accessed 5 June 2020.

CSPP - University of Strathclyde. (2014). Barometer Surveys. http://www.cspp.strath.ac.uk/catalog13_0.html. Accessed 5 June 2020.

Darley, J. M. (2005). The Cognitive and Social Psychology of Contagious Organizational Corruption. Brooklyn Law Review, 70(4), 1177–1194. http://heinonlinebackup.com/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/brklr70§ion=40

de Sousa, L. (2008). ‘I Don’t Bribe, I Just Pull Strings’: Assessing the fluidity of social representations of corruption in Portuguese Society. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 9(1), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/15705850701825402

de Sousa, L., Pinto, I. R., Clemente, F., & Gouvêa Maciel, G. (2020). Using a three-stage focus group design to develop questionnaire items for a mass survey on corruption and austerity: A roadmap. Qualitative Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-09-2020-0110

de Sousa, L., & Triães, J. (Eds.). (2008). A Corrupção e os Portugueses: Atitudes, Práticas e Valores. Cascais, Portugal: RCP Edições.

Dolan, K., McKeown, B., & Carlson, J. M. (1988). Popular conceptions of political corruption: implications for the empirical study of political ethics. Corruption and Reform, 3, 3–24.

Doorenspleet, R. (2019). Rethinking the value of democracy: A comparative perspective. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91656-9

Erlingsson, G. Ó., & Kristinsson, G. H. (2018). Exploring shades of corruption tolerance: Three lessons from Iceland and Sweden. QoG Working Paper Series, 5.

Erlingsson, G. Ó., & Kristinsson, G. H. (2019). Exploring shades of corruption tolerance: Tentative lessons from Iceland and Sweden. Kyiv-Mohyla Law and Politics Journal, 5, 141–164. https://doi.org/10.18523/kmlpj189994.2019-5.141-164

European Commission. (2014). Special Eurobarometer 397. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_397_en.pdf. Accessed 2 July 2016.

European Commission. (2017). Special Eurobarometer 470 Report: Corruption. Directorate-General for Communication. http://data.europa.eu/88u/dataset/S2176_88_2_470_ENG. Accessed 13 January 2019.

European Commission. (2018a). Special Eurobarometer 477 Report: Democracy and elections. http://data.europa.eu/88u/dataset/S2198_90_1_477_ENG. Accessed 28 August 2019.

European Commission. (2018b). ZA6927 Data file Version 1.0.0. Eurobarometer 88.2 (2017). TNS opinion, Brussels [producer]. GESIS Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13005

European Commission. (2020). Public Opinion. https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm. Accessed 5 June 2020.

European Values Study. (2019). ZA7500 Data file Version 2.0.0. European Values Study 2017 Integrated Dataset (EVS 2017). GESIS Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13314

Eurostat. (2020). Gini index (%). https://www.pordata.pt/en/DB/Europe/Search+Environment/Table/5811312. Accessed 28 April 2020.

Gardiner, J. A. (1970). The politics of corruption: Organized crime in an American City. New York, NY, USA: Russell Sage Foundation.

Gatti, R., Paternostro, S., & Rigolini, J. (2003). Individual attitudes toward corruption: Do social effects matter? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 3122. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-3122

Gibbons, K. M. (1989). Variations in attitudes toward corruption in Canada. In A. J. Heidenheimer, M. Johnston, & M. F. LaVigne (Eds.), Political corruption: A handbook. (pp. 165–171). New Brunswick, NJ, USA: Transaction.

Gouvêa Maciel, G., & de Sousa, L. (2018). Legal corruption and dissatisfaction with democracy in the European Union. Social Indicators Research, 140(2), 653–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1779-x

Guo, X., & Tu, W. (2017). Corruption tolerance and its influencing factors—the case of China’s civil servants. Journal of Chinese Governance, 2(3), 307–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/23812346.2017.1342897

Heidenheimer, A. J. (1970). Political corruption: Readings in comparative analysis. New York, NY, USA: Holt, Rinehart & Winston of Canada Ltd.

Heidenheimer, A. J., Johnston, M., & LeVine, V. T. (Eds.). (1989). Political corruption: A handbook. New Brunswick, NJ, USA: Transactions Publishers.

Hox, J. (2002). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. London, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hunady, J. (2017). Individual and institutional determinants of corruption in the EU countries: The problem of its tolerance. Economia Politica, 34(1), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-017-0056-4

ICAC. (2003). Community attitudes to corruption and the ICAC. Sydney, Australia: ICAC.

ICAC. (2006). Community attitudes to corruption and the ICAC: Report on the 2006 survey. Sydney, Australia: ICAC.

Inter-Parliamentary Union. (2020a). Compare data on Parliaments, Percentage of MPs 45 years of age or younger, Europe, Lower chambers and unicameral parliaments. Parline database on national parliaments. https://data.ipu.org/. Accessed 10 May 2020.

Inter-Parliamentary Union. (2020b). Compare data on Parliaments, Percentage of women, Europe, Lower chambers and unicameral parliaments. Parline database on national parliaments. https://data.ipu.org/. Accessed 10 May 2020.

Jackson, M., & Smith, R. (1996). Inside moves and outside views: An Australian case study of elite and public perceptions of political corruption. Governance, 9(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.1996.tb00232.x

Jobson, J. D. (1992). Applied Multivariate Data Analysis, Volume II: Categorical and Multivariate Methods. Springer Texts in Statistics. New York, NY, USA: Springer Science+Business Media.

Johnston, M. (1986). Right and wrong in American politics: Popular conceptions of corruption. Polity, 18(3), 367–391.

Johnston, M. (1991). Right and wrong in British Politics: “Fits of Morality” in comparative perspective. Polity, 24(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.2307/3234982

June, R., Chowdhury, A., Heller, N., & Werve, J. (2008). A User’s Guide to Measuring Corruption. Oslo, Norway: UNDP Oslo Governance Centre and Global Integrity.

Kaufman, L., & Rousseeuw, P. J. (1990). Finding groups in data: An introduction to cluster analysis. New Jersey, NJ, USA: Wiley-Interscience.

Kaufmann, D., & Vicente, P. C. (2011). Legal corruption. Economics and Politics, 23(2), 195–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0343.2010.00377.x

Keller, T., & Sik, E. (2009). The perception, the tolerance, and the practice of corruption. In I. G. Tóth (Ed.), TÁRKI European Social Report. (pp. 163–178). Budapest, Hungary: TÁRKI Inc.

Ko, K., Cho, S. Y., & Lee, J. (2012). The trend of the tolerance of gray corruption and its determinants: Citizens’ perception in Korea. In International Public Management Network Conference. Hawaii, USA.

Köbis, N. C., Iragorri-Carter, D., & Starke, C. (2018). A social psychological view on the social norms of corruption. In I. Kubbe & A. Engelbert (Eds.), Corruption and norms (pp. 31–52). Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66254-1_3

Köbis, N. C., van Prooijen, J.-W., Righetti, F., & Van Lange, P. A. M. (2015). “Who Doesn’t?”—The impact of descriptive norms on corruption. PLoS ONE, 10(6), e0131830. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131830

Kubbe, I. (2018). Europe’s “democratic culture” in the fight against corruption. Crime, Law and Social Change, 70(2), 217–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-017-9728-9

Lavena, C. F. (2013). What determines permissiveness toward corruption?: A study of attitudes in Latin America. Public Integrity, 15(4), 345–366. https://doi.org/10.2753/PIN1099-9922150402

Lessig, L. (2012). Institutional Corruptions. EUI Working Paper RSCAS, 68.

Lessig, L. (2013). Foreword: “Institutional Corruption” Defined. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics, 41(3), 553–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlme.12063

Malmberg, F. (2019). The Rotting Fish? Institutional Trust, Dysfunctional Contexts, and Corruption Tolerance: A multilevel study of the justification of low-level corruption in a global perspective. PhD Thesis. Åbo, Finland: Åbo Akademi University. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-765-945-1

Mancuso, M., Atkinson, M. M., Blais, A., Greene, I., & Nevitte, N. (2006). A question of ethics: Canadians speak out (Revised ed.). Toronto, Canada: Oxford University Press.

Mann, H., Garcia-Rada, X., Houser, D., & Ariely, D. (2014). Everybody else is doing it: Exploring social transmission of lying behavior. PLoS ONE, 9(10), e109591. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109591

Mingo, I., & Faggiano, M. P. (2020). Trust in institutions between objective and subjective determinants: A multilevel analysis in European Countries. Social Indicators Research, 151(3), 815–839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02400-0

Modesto, J. G., & Pilati, R. (2020). “Why are the Corrupt, Corrupt?”: The multilevel analytical model of corruption. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 23(e5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2020.5

Moreno, A. (2002). Corruption and democracy: A cultural assessment. Comparative Sociology, 1(3), 495–507. https://doi.org/10.1163/156913302100418556

Morris, M. W., Hong, Y., Chiu, C., & Liu, Z. (2015). Normology: Integrating insights about social norms to understand cultural dynamics. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 129, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2015.03.001

Mulyana, A., Iskandarsyah, A., Siswadi, A. G. P., & Srisayekti, W. (2019). Social value orientation on corruption prisoners. MIMBAR: Jurnal Sosial dan Pembangunan, 35(1), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.29313/mimbar.v35i1.4479

National Taiwan University. (2016). Asian Barometer Survey. http://www.asianbarometer.org/survey. Accessed 5 June 2020.

Navot, D., & Beeri, I. (2018). The public’s conception of political corruption: A new measurement tool and preliminary findings. European Political Science, 17(1), 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-016-0079-2

Philp, M. (1997). Defining political corruption. Political Studies, 45(3), 436–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00090

Pisor, A. C., & Gurven, M. (2015). Corruption and the other(s): Scope of superordinate identity matters for corruption permissibility. PLoS ONE, 10(12), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144542

Pop, I. (2012). Acceptance of corrupt acts: A comparative study of values regarding corruption in Europe. Journal of Social Research and Policy, 3(1), 27–42.

Pozsgai-Alvarez, J. (2014). operationalizing high-level corruption tolerance in Peru : Attitude-behavior congruency and the 2006 presidential elections. Area Studies Tsukuba, 35, 183–206. http://hdl.handle.net/2241/00123531

Pozsgai-Alvarez, J. (2015). Low-level corruption tolerance: An “action-based” approach for Peru and Latin America. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 7(2), 99–129.

Pozsgai-Alvarez, J. (2020). The abuse of entrusted power for private gain: Meaning, nature and theoretical evolution. Crime, Law and Social Change, 74(4), 433–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-020-09903-4

Reporters sans frontières. (2020). 2018 World Press Freedom Index. https://rsf.org/en/ranking/2018. Accessed 8 May 2020.

Rohac, D., Kumar, S., & Johansson Heinö, A. (2017). The wisdom of demagogues: Institutions, corruption and support for authoritarian populists. Economic Affairs, 37(3), 382–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecaf.12264

Salgado, S. (2019). Where’s populism? Online media and the diffusion of populist discourses and styles in Portugal. European Political Science, 18(1), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-017-0137-4

Sautu, R. (2002). La Integración de Métodos Cualitativos y Cuantitativos para el Estudio de las Experiencias de Corrupción. Cinta de Moebio, (13). http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=10101314

Tavits, M. (2008). Representation, corruption, and subjective well-being. Comparative Political Studies, 41(12), 1607–1630. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414007308537

Tavits, M. (2010). Why do people engage in corruption? The Case of Estonia. Social Forces, 88(3), 1257–1279.

Tay, L., Herian, M. N., & Diener, E. (2014). Detrimental effects of corruption and subjective well-being. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(7), 751–759. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550614528544

Thompson, D. F. (1995). Ethics in congress: From individual to institutional corruption. Washington, DC, USA: Brookings Institution.

Thompson, D. F. (2013). Two concepts of corruption. Edmond J. Safra Research Lab Working Papers, 16, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2304419

Torgler, B., & Valev, N. T. (2006). Corruption and age. Journal of Bioeconomics, 8(2), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10818-006-9003-0

Transparency International. (2018). Corruption Perceptions Index 2018: Global Scores [Full Dataset]. https://www.transparency.org/cpi2018. Accessed 13 November 2019.

Transparency International. (2020a). Corruption Perception Index. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi. Accessed 28 June 2020.

Transparency International. (2020b). Global Corruption Barometer. https://www.transparency.org/en/gcb. Accessed 5 June 2020.

Waheeduzzaman, A. N. M. (2005). Tripolar world of corruption and inequality: Again, the difference is in freedom and governance. Journal of Transnational Management Development, 9(4), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1300/J130v09n04_04

World Bank. (2019). 2018 GDP per capita, PPP (current international $). World Bank, International Comparison Program database. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD. Accessed 13 November 2019.

Wu, J. (2012). Advances in K-means clustering: A data mining thinking. Springer Theses: Recognizing outstanding Ph.D. research. New York, NY, USA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-29807-3

Wysmułek, I. (2019). Using public opinion surveys to evaluate corruption in Europe: Trends in the corruption items of 21 international survey projects, 1989–2017. Quality and Quantity, 53(5), 2589–2610. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-019-00873-x

Zhao, H., Zhang, H., & Xu, Y. (2019). Effects of perceived descriptive norms on corrupt intention: The mediating role of moral disengagement. International Journal of Psychology, 54(1), 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12401

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the reviewers and to the ICS-UL community, especially to Luís de Sousa, Pedro Magalhães, Alda Botelho Azevedo, Efstratios-Ioannis Kartalis, Amílcar Moreira, and Marcelo Camerlo. I also thank Marina Costa Lobo and Carlos Jalali for the opportunity to present and discuss the development of this article at the regular ICS-SPARC (Social and Political Attitudes: Resilience and Change) forum and during the first ICS-UA PhD meeting on Comparative Politics, respectively. Needless to say, the author is solely responsible for the contents and any errors and omissions that may be detected in the article.

Funding

This work was financed by the Doctoral Degree Scholarship Program of the University of Lisbon (Grantee No. 746/2018). It was also developed under the auspices of the research project ‘EPOCA: Corrupção e crise económica, uma combinação perigosa: compreender as interacções processo-resultado na explicação do apoio à democracia’ (Ref.: PTDC/CPO-CPO/28316/2017), funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia—FCT, Portugal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gouvêa Maciel, G. What We (Don't) Know so Far About Tolerance Towards Corruption in European Democracies: Measurement Approaches, Determinants, and Types. Soc Indic Res 157, 1131–1153 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02690-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02690-y