Abstract

This paper aims to define a theoretical background for investigating greenwashing from a business economic perspective. We consider possible research questions in the relevant field of study, which is business economics studies. The first research step proposes a path that will orient scholars to the multifaceted perspectives of greenwashing. The second step analyzes the main theories that can support researchers and might motivate the possible greenwashing strategies. The third step highlights the potential link between greenwashing, reputational and relational capital, and a broad concept of value that includes the social dimension. Finally, we propose a conceptual framework that highlights some emerging research issues and anticipates the effects of greenwashing. Considering that self-regulation is not effective in reducing the gap between substantive and symbolic behaviors, the main practical implication of this study lies in addressing the need for stronger regulation and effective legal enforcement, not only to improve mandatory environmental disclosure but also to develop an audit process of such disclosure. Our analysis offers a number of suggestions for future research. Considering the centrality of disclosure in the theoretical framework we defined for greenwashing, future research could adopt the legitimacy theory perspective to focus on the role of mandatory environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) disclosure as well. Further, our conceptual framework highlights a possible research issue that investigates how a social value destruction resulting from inconsistent environmental strategies, may impact shareholders’ economic value.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Companies are aware that environmental risks are a threat to their competitiveness and survival. For this reason, they should consider those risks, in order to define their position in the field of social responsibility and also to contribute to their value creation processes (Seele & Schultz, 2022). Further, the need to operate in an inconstant environmental context, which is a consequence of the recent economic-financial crisis, the pandemic, and the current war, shapes the effort toward reaching environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) objectives. These recent occurrences push the researcher to investigate the role sustainability assumes as a possible resilience tool, in a process oriented to create economic and social value (Lee & Raschke, 2023).

The above considerations shed light on the essential role of corporate voluntary disclosure in legitimizing companies’ behaviors on the one hand, and emphasizes the need for developing a mandatory body of ESG information, on the other (Mahoney et al., 2013; Perera et al., 2019).

Greenwashing is a phenomenon arising from companies’ need to “resolve” the trade-off between the increasing importance of environmental compliance and their real and supportable efforts toward this objective. The word “greenwashing” is derived from the combination of “green” and “brainwashing” (Mitchell & Ramey, 2011), where brainwashing is applied to an environmental context. Greenwashing is a disclosure-based strategy (Lee & Raschke, 2023; Seele & Schultz, 2022; Seele & Gatti, 2017; Cooper et al., 2018) that may depend on some external conditions, incentives, or pressures that characterize the institutional context in which the strategies of deceptively disclosing “green” activities occur (Zharfpeykan, 2021; Velte, 2022; Marquis et al., 2016; Seele & Schultz, 2022; Li et al., 2023). This highlights that the institutional setting is a crucial determinant of companies’ environmental responsibility effectiveness (Li et al., 2023; Marquis et al., 2016).

Academics have not yet uniquely defined the role of environmental sustainability. In fact, scholars (e.g., Bini et al., 2018) speculate whether it is the most important challenge in the current socio-economic context or whether it is a “matter” that ought to be managed to maintain the company’s competitive advantage or to improve its financial performance. However, recent studies show ambiguous results regarding the effects of ESG practices on financial performance (Lee & Raschke, 2023; Li et al., 2023). Regarding environmental sustainability the argument is that financial performance can be supported by making restricted efforts via the use of misleading communication, since stakeholders cannot identify companies’ actual behavior, nor recognize asymmetric information (Berrone et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018; Zharfpeykan, 2021).

Our literature review sheds light on some research issues to be deeply investigated to comply with the needs of scholars seeking a strong and reliable theoretical foundation for defining greenwashing (Lyon & Montgomery, 2015; De Jong et al., 2020; Gatti et al., 2021). It also highlights calls from authorities and regulators who need a definition that could be useful for the controlling authorities to “understand greenwashing” (e.g., ESA, 2022).

Despite the widespread use of non-academic definitions of greenwashing (e.g., Oxford English Dictionary; Greenpeace, 2021; TerraChoice, 2007), there is also the need to organize a theoretical path that will be useful for understanding the multifaceted perspectives of greenwashing (Lyon & Montgomery, 2015), also due to the interdisciplinary impact that greenwashing generates. In fact, greenwashing might generate impacts felt in several fields of study such as sociology, psychology, and law (i.e., legality, rulings, corruption) and ones that reflect on, among others, the role of corporate disclosure, financial performance and value, or strategy and marketing.

Our work aims to provide an inclusive outlook on the different interpretations of the greenwashing concept, by proposing a comprehensive view of greenwashing-related features. It also considers motivations of greenwashing by adapting certain theories developed in a socio-political context, as well as those related to voluntary disclosure, referring also to greenwashing strategies (Uyar et al., 2020; Mahoney et al., 2013; Delmas & Burbano, 2011). Our research ultimately defines a conceptual framework by analyzing potential links between greenwashing, reputational and relational capital, and a broad concept of value that includes its social dimension.

Our conceptual framework could become a background for future empirical testing of the research questions arising from the analysis of greenwashing in a business economic perspective. For the analysis, we adopted a qualitative research method. Starting from these pointers, this paper aims also to clarify a number of emerging and relevant issues from a qualitative research perspective and to develop a theoretical background for investigating the determinants and the potential effects of greenwashing in business economics studies, also articulating possible research questions.

The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we illustrate the methodology we adopted to develop our research. Next, we illustrate the institutional background’s main features and its possible role as a greenwashing driver (Delmas & Burbano, 2011) in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4 we propose a path for orienting scholars to the multifaceted perspectives of greenwashing. In fact, scholars have emphasized the need for a review of the greenwashing concept (Lyon & Montgomery, 2015; De Jong et al., 2020; Gatti et al., 2021). To foster a broader visualization of the greenwashing concept in an academic framework, we propose a visualization organized according to the most acknowledged features of the concept. Subsequently, in Sect. 5, we analyze the main theories that might support researchers and motivate the possible greenwashing strategies. Then, in Sect. 6, we highlight the potential link between greenwashing, reputational and relational capital, and a broad concept of value that includes the social dimension. Also, we propose a conceptual framework that can highlight various emerging research issues and that anticipates the greenwashing effects, also suggesting an agenda for future research. Finally, Sects. 7 and 8 give the discussion and the conclusions, respectively.

2 Methodology

Our research aims to design a conceptual framework for developing research in the CSR field (Kurpierz & Smith, 2020), with a specific focus on environmental issues. The environmental dimension of CSR could be susceptible to a particular phenomenon identified as greenwashing.

To develop our conceptual framework, we defined a four-step research design adopting a qualitative research method and starting from a literature analysis.

Our literature review started with an analysis of a set of papers extracted from the Scopus database. We focused on relevant articles published between 2000 and 2023 because research on greenwashing from business administration and management perspectives before 1990 is scant, and between 1990 and 2000 we found only three papers which were not directly relevant to our work. We searched for articles written in English to avoid inconsistencies related to the language.

Since greenwashing is a multifaceted concept, our search used keywords that would identify all the definitions of this kind of strategy. Starting from the reading of the relevant literature, we recognized that the following terms were widely used: “greenwashing”; “green-washing”; “greenwash”; “green-wash”; “green strategies”; “green washers”. To include all the uses of these terms, we chose the root-words “green” and “wash” in the title, the abstract, and the keywords.

The application of the above criteria resulted in a first extraction of about 335 articles. Using this full set, we started selecting by excluding the papers that are not incorporated in the list of Chartered ABS Journals and those not pertinent to greenwashing from management and from business administration perspectives. These further criteria left us with a set of 59 articles. Nine of these articles, although they were broadly relevant to the topic, were not useful for the purpose of our study because they did not include the issues we aimed to consider in our review. Therefore, the final number of papers was 50.

Specifically, we set up the literature analysis to collect, among the other information, definitions of greenwashing in recent research, to individuate the relevant pillars (milestones), the research questions these papers investigated, the theories they drew on, and the emerging issues regarding the relation between greenwashing and value drivers.

To finalize the literature review, we carefully read all pertinent papers to determine which components should be examined, and we eventually settled on the list of four given in Table 1 below. Aiming to classify the papers according to the component(s) they analysed, we found several intersections because some papers included more than one issue. For instance, four papers included all the clusters, while other articles included one, two, or three of them, as Table 1 shows.

Our analysis of greenwashing literature shows several possible aspects that should be investigated or that are still unclear.

A primary question concerns the conceptualization of this phenomenon. On the one hand, scholars mention that research on symbolic corporate environmentalism and greenwashing is currently still scant (Martín-de Castro et al., 2017; Testa et al., 2018b) and that there is evident risk of investigating greenwashing in an overly simplistic way (De Jong et al., 2020; Gatti et al., 2021) or without a strong and reliable theoretical foundation (Lyon & Montgomery, 2015). Also, most of the extant studies observe greenwashing in its relation to stakeholders and their perceptions (Torelli et al., 2019). For this reason, research regarding the companies’ perspective needs greater attention (Gatti et al., 2021). At the same time, the European supervisory authorities need for appropriate definition of greenwashing that can be used in the EU regulatory framework.

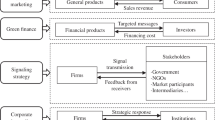

The literature analysis was instrumental in delineating the scope of our theoretical investigation. Our review gave insight regarding the direction in which greenwashing should be oriented and organized within a strong theoretical framework (Fig. 1) with the following components: (1) the institutional background related to the issue of greenwashing and possible links to corporate governance; (2) the greenwashing concept that we realize by categorizing the several definitions of greenwashing into “orienting pillars” on which we build in defining a construct for a comprehensive and organized view on the most pertinent greenwashing features; (3) the conceptual organization and recognition of the main theories capable of explaining greenwashing and motivating greenwashers’ behavior (Delmas & Burbano, 2011), thus supporting research devoted to this issue; (4) the definition of a potential link between greenwashing, reputational capital and relational capital, and a broad concept of value that includes its social dimension. In fact, the effects of greenwashing strategies should be matched with the expansion of the boundaries of the concept of value. Our aim overall, therefore, is to draw a connecting line that will link greenwashing and value, thereby proposing our framework as a tool for developing future research.

3 The role of institutional background and of corporate governance issues

Greenwashing strategies and their intensity could be better understood by considering underlying matters regarding two important issues, namely the institutional context (external factors related to a given country and its social actors) and the corporate governance (a company-related factor) (Velte, 2022).

Greenwashing is a disclosure-based strategy (Lee & Raschke, 2023; Seele & Schultz, 2022; Seele & Gatti, 2017; Cooper et al., 2018) that might depend on certain external conditions, incentives, or pressures that characterize the institutional context in which these strategies are used (Zharfpeykan, 2021; Velte, 2022; Marquis et al., 2016; Seele & Schultz, 2022; Li et al., 2023) or that are shared within the global context. Mostly, companies aim to conform to the institutional context to which they belong, which is composed of a social system, legislation, and the norms and rules that govern firms’ activities (Guo et al., 2017). In fact, firms fear the reputational damage they might suffer from a transgression of global environmental norms and, consequently, they deceptively moderate their disclosure intending to address the reputational threat (Marquis et al., 2016).

Very many international institutions aim to promote sustainable development. Focusing on the foremost international agreements, which have been defined in the second decade of the 2000s, a set of “milestones” of the logic underlying the ESG commitment can be identified (Table 2).

The first milestone was stipulated in 2015 in an agreement signed by all 193 countries of the United Nations, i.e., the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” which defines the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be achieved by 2030. One of the sustainable development targets the United Nations identified refers to reporting, specifically encouraging companies to disclose information that demonstrates their commitment to sustainability.

Also in 2015, 195 members of the “United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change” signed the Paris Agreement, which took effect in 2016 and aimed to strengthen the global response to the risk of climate change.

Further, in 2018, the European Commission drafted the EU Sustainable Finance Action Plan of which the main objective was to incentivize the financing of sustainable activities, to include sustainability in risk management systems, and to foster increasing transparency in reporting these issues. Therefore, this Action Plan helped to implement the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda. Particularly, one of its actions resulted in the creation of EU brands for so-called “green” financial products, to signal investment opportunities that are aligned with environmental criteria which investors should therefore consider. This generated a classification system for sustainable activities, known as the “EU Taxonomy” which, among other things, had some effects on reporting quality. To achieve a better basis of comparison than before, the taxonomy redefined environmental reporting according to a logic of accountability, which is as broad and standardized as possible. It, therefore, represents a deterrent to greenwashing and defines a model for evaluating corporate strategies according to a perspective oriented toward sustainability.

In 2019, the European Commission announced the European Green Deal, which defined some measures, including actions aimed at reducing CO2 emissions responsible for climate change by the year 2030, and at eliminating those emissions by the end of 2050. Together with the 2030 Agenda, the European Green Deal has promoted a strong push to facilitate reliable reporting on the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

Although requirements regarding mandatory disclosure have been increased in recent years, the literature claims that mandatory environmental disclosure is still scant (Mahoney et al., 2013). In fact, mandated reporting requirements appear to constrain the propensity to divulge misleading information (Perera et al., 2019).

Among the few cases of mandatory reporting requirements, the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) realized by the Financial Stability Board in 2015 deserves attention. In the absence of conventional international climate-related reporting standards, this group aims to create a set of voluntary disclosure indicators regarding climate-related risks (Brooks & Schopohl, 2020). The TCFD drives companies to give answers regarding risks and opportunities related to climate change (Dye et al., 2021; Seele & Shultz, 2022). Although originally issued as a voluntary information set, in 2021 the TCFD regulations became mandatory for the UK’s financial services sector (Reilly, 2021).

Focusing on the European context, the current regulatory setting related to sustainability disclosure is based on several regulations, of which the first is Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, which took effect in 2017, and which is mandatory only for specific categories of companies. This Directive introduced the requirement for some large companies to include a non-financial disclosure in the management report, concerning the ESG factors, which are considered relevant regarding the activities and the company characteristics.

Next, in 2019, Regulation n. 2088 of the European Parliament and of the Council was issued. It represents a new Sustainability-related Financial Disclosure Regulation, which came into force in the second quarter of 2021, requiring mandatory disclosure by fund managers on how they integrate sustainability in investment processes and contain potentially adverse impacts of investments on achieving sustainability goals. This regulation also introduced the distinction between “products” that simply promote environmental or social characteristics (Article 8) and “products” that aim to ensure sustainable investments (Article 9).

The EU directive 2022/2464, in force since January 2023, took on a crucial role regarding corporate sustainability reporting (CSRD) that substitutes the Non-Financial Reporting Directive with “sustainability information”. Significantly, this innovation underlines that information on sustainability cannot be qualified as non-financial and it invites companies to consider the impact sustainability considerations have on their financial plan; thus, financial disclosure and ESG disclosure processes are suitably aligned. Also, this Directive eliminates the likelihood of disclosing CSR separately from the financial report. Separate reporting is directed at different groups of stakeholders, while integrated reporting addresses investors. If the company includes sustainability information in the integrated report it signals that they consider it useful for stakeholders, shareholders (Velte, 2022), and for civil society actors. Additionally, in this way sustainability information will be subject to assurance and double materiality analysis.

Before the 2022 EU Directive, various standard-setting institutions, such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), already promoted the development of sustainability disclosure by providing a set of sustainability accounting standards (Bini et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2020; Dye et al., 2021; Lashitew, 2021; Laufer, 2003). Even so, until now specific mandatory requirements and their enforcement are still lacking. For this reason, stakeholders have not been able to fully assess the quality and the truthfulness of companies’ environmental claims.

By gradually applying the CSRD to a broader set of companies, enforcing the effectiveness of the sustainability report standards could be facilitated. In fact, the CSRD has designated the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) to issue the Sustainability Reporting Standards, which will become mandatory for EU companies in the next few years.

Despite such recent improvements, scholars find that environmental disclosure is not widely audited (Yu et al., 2020; DeSimone et al., 2021). Further, voluntary disclosure can be done strategically to communicate misleading environmental claims (Zharfpeykan, 2021). This could give rise to information asymmetries and, consequently, foster greenwashing strategies (Gugerty, 2009).

Several sources, such as annual reports, corporate social responsibility reports (i.e., sustainability reports, environmental reports, etc.), the mass-media, or websites (Dye et al., 2021; Mahoney et al., 2013) transmit voluntary disclosure regarding environmental commitment. In fact, as Mahoney et al. (2013) found, in the absence of mandatory environmental disclosure, the amount of information voluntarily disclosed depends also on the pressure stakeholders exert on the companies (Lee & Raschke, 2023). However, when mandatory requirements are scant or weak, stakeholders are not able to estimate whether a firm is really committed to environmental issues. In their recent study, Li et al. (2023) strongly emphasize the relevance of regulations and of the so-called social scrutinizers, also in weakening the positive relationship between greenwashing and financial performance.

Since the regulatory environment is a fundamental determinant of greenwashing (Li et al., 2023; Delmas & Burbano, 2011), the lack of mandatory requirements allows companies to report only useful information that is considered good in sustainability terms. Consequently, the quality of environmental disclosure is very variable across different companies and properly understanding whether information is trustworthy or not, is not fostered among stakeholders. This creates a favorable context for accomplishing greenwashing legitimization strategies, since stakeholders rely on the signaling power of disclosure (Yu et al., 2020). In fact, as Khan et al. (2021a, b) state, disclosure regarding sustainability has recently been criticized for being “opportunistic, “green washing”, implausible, cosmetic, lacking in stakeholder inclusivity, lacking in “authentic effort” and failing to meet users’ expectations” (p. 339), and largely unreliable. Since voluntary disclosure on environmental issues is a strategic tool for companies to answer to stakeholders’ pressure and to achieve legitimation, it could be lacking in reliability (Lashitew, 2021).

Greenwashing is related to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), defined in the literature as “a model of extended corporate governance whereby those who run a firm (entrepreneurs, directors and managers) have responsibilities that range from fulfillment of their fiduciary duties towards the owners to fulfillment of analogous fiduciary duties towards all the firm’s stakeholders” (Sacconi, 2006, p. 262). This perspective on businesses’ social responsibility incorporates sustainability into a broader view of corporate governance (DeSimone et al., 2021), which includes the influence managers exert, as well as how the relationship between owners and managers affects their firms’ sustainability behaviors (Fiandrino et al., 2019; Jain & Jamali, 2016). This view further includes the mechanisms that regulate the fiduciary relationships which engage stakeholders and influence companies’ reputation (Li et al., 2023), even in terms of environmental sustainability (Fiandrino et al., 2019).

The link between corporate governance, management, and greenwashing, as we explain more elaborately below, can be observed through several lenses, such as the role of disclosure-based strategies, the governance control mechanisms, and the accusation element. Further, it should be noted that greenwashing strategies and their intensity, among other things, can depend on firm-related factors, external stakeholders’ pressures or awareness, or institution-related and country-related factors (Velte, 2022).

The literature sheds light on possible institutional features, as well as specific corporate governance attributes capable of impacting on the disclosure quality, and therefore also on reporting-related strategies, such as greenwashing. Velte (2022) observes some context-related issues that enlighten us on the stakeholders’ influence and involvement in corporates decisions. In fact, he states that operating within a civil regime means that a stakeholder’s perspective is adopted. Further, the degree of stakeholders’ influence on firms’ compliance and on their boards of directors can strengthen the investors’ protection rules (Jamali et al., 2008). In addition, the institutional context can be characterized according to the level of scrutiny and the kind of pressure certain social actors such as NGOs, consumers, investors, environmental groups (Kim & Lyon, 2011; Marquis et al., 2016; Testa et al., 2018aa; Seele & Schultz, 2022) exert. Such actors can impose their own supervision by introducing their own mandated disclosure requirements or monitoring actions, which the regulatory environment will carry out (Delmas & Burbano, 2011).

That greenwashing is a pertinent matter is evident from observing how regulators pay attention to it. In fact, European regulators have already signaled a willingness to take enforcement action in cases of greenwashing. For instance, in 2022 the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) established that the national regulators should enforce actions devoted to countering greenwashing. Also, the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) published a Call for Evidence on greenwashing to find a clear definition of the phenomenon through developing a deeper understanding of its key-features, its drivers, and the related risks, as well as to shed light on possible practical manifestations of greenwashing. This commitment of the European Supervisory Authorities contributes to new insight on the fact that greenwashing has become a complex and not well-defined phenomenon. The conceptual framework we propose in this complex scenario aims to disambiguate some issues in the path that scholars tread in developing research devoted to sustainability, with a particular focus on greenwashing as an environmental matter.

We recognize the role of corporate governance in a greenwashing analysis by observing several research directions such as greenwashing in disclosure-based strategies, governance control mechanisms, and an accusation element.

Corporate governance drivers, such as the boards of directors, the executive committee, and owners with specific attributes (Ho, 2005), are recognized as strong determinants of the reporting quality that, in turn, constrains the risk that companies incur in greenwashing strategies (Velte, 2022). For example, both stakeholders and shareholders can foster an improvement of the reporting quality, but at the same time greenwashing can arise from an opportunistic manager’s intent. In fact, both internal and external determinants act in driving or limiting greenwashing. On the one hand, governance bodies such as the board of directors, as well as external stakeholders can constitute a fostering factor for executives who have to implement disclosure strategies. On the other hand, corporate governance mechanisms act as controlling instruments to improve the disclosure quality and therefore to constrain the strategies that build information asymmetries (Velte & Stawinoga, 2017).

The link between greenwashing and governance from a control perspective is also clarified by professional accountants and auditors who hold that implementing an ESG governance is a way of constraining greenwashing: “Embed ESG criteria in existing risk management procedures and controls. Consider introducing a bespoke ESG policy. ESG governance can assist the business to follow and have evidence of robust processes to make accurate public statements and claims about how ‘green’ or sustainable their products and services are” (KPMG, 2022).

The above considerations suggest a need to observe corporate governance’s role as a firm-level determinant of greenwashing because, due to the control mechanisms that the board of directors can implement, governance can be a possible incentive to disclose legitimation strategies and a possible limit to the disclosure tendency.

Further, greenwashing is a strategy that arises through stakeholder involvement. Specifically, greenwashing results when external interlocutors formulate an accusation (Sutantoputra, 2022) or attribute blame (Pizzetti et al., 2021). Such accusations, in certain cases, can act as a limiting element, for example, in vigilant environmental NGOs (Berrone et al., 2017). In fact Seele and Gatti (2017, p. 239) state that greenwashing is a phenomenon “constituted in the eye of the beholder, depending on an external accusation.” In other words, greenwashing emerges from a path that involves reporting, controls, and strategies, and is a consequence of some form of control. Reporting-related strategies, such as greenwashing, are also strictly linked to the control external interlocutors exercise (Li et al., 2023).

4 Perspectives for a greenwashing conceptualization

In the broader context of CSR, the greenwashing concept relates specifically to the environmental responsibility of a firm (Pearson, 2010). Greenwashing arises as firms are increasingly being requested to commit to environmental issues, and is fostered by the difficulties stakeholders encounter in directly evaluating a firm’s environmental performance (Berrone et al., 2017; Pizzetti et al., 2021). Due to these difficulties, firms can afford to communicate non-transparent information about their environmental performance.

As research on greenwashing is growing, several greenwashing-related issues will be developed. However, different scholars portray different meanings of greenwashing (Walker & Wan, 2012; Seele & Gatti, 2017; Zharfpeykan, 2021) and, currently, there is no generally accepted understanding of the concept (Torelli et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). There are several definitions of greenwashing that are grounded in different perspectives, which is due also to greenwashing being multifaceted (Lyon & Montgomery, 2015) so that an interdisciplinary perspective is fostered (Seele & Gatti, 2017; Torelli et al., 2020; Zharfpeykan, 2021).

The above features of the greenwashing phenomenon suggest a lack of homogeneity, which leads to the first step in developing our framework. We propose a conceptual scheme to orient scholars and authorities toward understanding the multifaceted features of greenwashing.

The origins of the concept greenwashing can be traced back to a study by the environmentalist and biologist Jay Westervelt, published in 1986 (De Freitas Netto et al., 2020), at a time when the first environmental controversies began to arise. In his essay, Westervelt accused firms operating in the hospitality sector of encouraging the reuse of towels, ostensibly to promote green policies; however, at the time he noticed that hospitality sector firms, in fact, did not promote serious environmental policies (Pearson, 2010; Seele & Gatti, 2017).

Greenwashing is considered “an umbrella term for a range of corporate behaviors that induce investors and others to hold an overly positive view of the firm’s performance” (Cooper et al., 2018, p. 227). Academics have, therefore, adopted various perspectives in defining the phenomenon of greenwashing (Torelli et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). Despite the differences in interpretation, the literature largely considers the definitions that scholars have formulated to be consistent with each other (Zharfpeykan, 2021).

We propose a conceptualization that polarizes the several definitions of greenwashing into some “orienting pillars.” Our literature analysis reveals that among the several definitions of greenwashing a number of recurring features can be recognized. In other words, most of the existing and recent definitions can be traced back to ones that identified the basic pillars. We aim to organize these basic pillars to define a construct that affords a wider and organized view on the possible features of greenwashing. All the conceptualizations of greenwashing have a common root in their use of disclosure as a tool to realize these strategies.

The first perspective we put in evidence, refers to omissions in reporting on the reality. The literature recognizes this as “selective” disclosure. In reporting a company’s activity, two possible kinds of behavior represent selective disclosure (Crifo & Sinclaire-Desgagné, 2013), namely to withhold information on negative environmental performances and/or to enhance the positive environmental performances disproportionately (Lyon & Maxwell, 2011; Guo et al., 2017, Torelli et al., 2020; Delmas & Burbano, 2011; Du, 2015; Marquis et al., 2016). Lyon and Maxwell’s (2011) definition is among the most widely recognized ones, describing greenwashing as “the selective disclosure of positive information about a company’s environmental or social performance, without fully disclosing the negative information on these dimensions, so as to create an overly positive corporate image” (p. 9). In other words, Lyon and Maxwell’s perspective considers greenwashing as an asymmetric communication that aims to report a company’s environmental successes, while hiding poor commitment or negative behavior (Ferrón-Vílchez et al., 2020). This perspective includes a stream of research that considers this kind of greenwashing as “cheap talk” (Cooper et al., 2018), incomplete disclosure (Martinez et al., 2020), and an intrinsic feature (Lee & Raschke, 2023). Also, this research stream sees omissions as a manipulation strategy (Cho et al., 2022) which paves the way for the second perspective of a greenwashing definition. In fact, quite close to the concept of selective disclosure, is the one of misleading disclosure (Delmas & Burbano, 2011; Du, 2015; Pope & Wæraas, 2016; Seele et al., 2017; Guix et al., 2022; Lee & Raschke, 2023). Laufer (2003) described CSR disclosure, to which disclosures regarding environmental performance and initiatives belong, as devious and insincere. This suggests that greenwashing results not only from “omissions” but also from “lies” in the form of false green reporting (Seele & Gatti, 2017) that shows an untruthful image of a company’s green behavior (Mitchell & Ramey, 2011). Consistent with this perspective, prior literature associates greenwashing with fraud, assuming that misleading claims are intentionally finalized to generate a damaging image/experience for readers (Kurpierz & Smith, 2020).

A third perspective focuses on the gap between what companies report and what they do. This happens when companies ‘don’t walk the talk’ (Berrone et al., 2017). This approach regards greenwashing as a lack of substance concerning what has been accomplished (Siano et al., 2017). Consistent with this view, Walker and Wan (2012, p. 231) define greenwashing as “symbolic information emanating from within an organization without substantive actions. Or, in other words, discrepancy between the green talk and green walk.” Walker and Wan’s (2012) concept of greenwashing diverges from “green highlighting” because, while the former stems from a gap between actions and reporting (Lyon & Montgomery, 2015), the latter is backed by substantive acts, although they select only the good performances for the report. However, both these strategies can produce stakeholder reactions, potentially resulting in reputational damage or in increased reputational risk (Gatzert, 2015). Prior literature proposed perspectives that highlight the relationship between the different pillars generating a construct, which involves more than a specific greenwashing feature.

Starting from the common concept of deception, Gatti et al. (2021) identified four possible ways of pursuing greenwashing strategies, which involve the abovementioned fundamental greenwashing features. Greenwashing can arise at the action level or at the communication level. The fundamental features of “selective-disclosure” and the “misleading-disclosure” arise when the respective strategy is pursued through communication. The first when deception is passive, the second when deception is active.

The action level of greenwashing suggests an additional consideration, asking whether greenwashing is a disclosure-based strategy at all. The symbolic form of greenwashing, introduced above, becomes manifest in active deception regarding greenwashing, which Gatti et al. (2021, p. 229) identify as happening when “(t)he company manipulates business practices to support its environmental communications.” Although such typology belongs to the action level, we see the manipulation of the business practices as a way of fostering positive but inconsistent reporting, thus including disclosure as an ultimate tool for greenwashing strategies. The action-level, associated with a passive form of deception, generates an additional feature of greenwashing, namely attention diversion. Attention diversion occurs when companies carry out green initiatives intended to be disclosed, while aiming to conceal other critical issues.

The literature recognizes that the extent of greenwashing, as well as its results, reflects some characteristics of the institutional background within which companies operate (Berrone et al., 2017; Delmas & Burbano, 2011). With this in mind, we complete our conceptual vision of greenwashing by giving the perspectives some important actors in the social environment, such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), have adopted. Since these actors actively scrutinize and monitor companies (Lee & Raschke, 2023), greenwashing might not be a successful strategy for them if they operate in the presence of vigilant environmental NGOs. These organizations might constrain the effects companies hope to achieve through greenwashing (Berrone et al., 2017). Two of the most important environmental NGOs, Greenpeace and TerraChoice, in their definition of greenwashing, emphasize a relational aspect that involves the customers and the products. Greenpeace defines greenwashing as “a public relation tactic that’s used to make a company or product appear environmentally friendly without meaningfully reducing its environmental impact” (Greenpeace, 2021), while TerraChoice defines greenwashing as “the act of misleading consumers regarding the environmental practices of a company or the environmental performance and positive communication about environmental performance” (TerraChoice, 2007). The perspectives these two NGOs definitions take offer a vision of greenwashing that is consistent with both the misleading and the symbolic pillars.

The background of greenwashing perspectives that we have represented sheds light on an important question to be addressed in future research: Can green communication also involve unethical or illegal behavior? (Siano et al., 2017). Indeed, considering greenwashing as the result of a selective or deceptive form of communication opens this concept to the possibility of including criminal or irresponsible environmental behavior, while adopting an interpretation of greenwashing as mere symbolic disclosure highlights the question of the inconsistency of companies’ reporting.

These considerations open up a further possible interpretation of greenwashing that places it between “decoupling” and “attention deflection” (Siano et al., 2017). Consistent with the concept of symbolic environmental disclosure, decoupling (Siano et al., 2017; Walker & Wan, 2012; Guo et al., 2017; Pizzetti et al., 2021) occurs when companies communicate good environmental actions to satisfy stakeholders’ needs and expectations without having adequate, structured, and organized activities, even to achieve their own objectives (Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Bromley & Powell, 2012). Attention deflection, on the other hand, aims to conceal irregular or unethical environmental behaviors (Marquis & Toffel, 2012) while reporting about symbolic “green behaviors.” Decoupling and deflection are both strategies that give communication a predominant role over action.

The background of the greenwashing definitions suggests some common attributes of these kinds of strategies. First, the literature has emphasized that greenwashing exists if this kind of environmental reporting is intentional (Torelli et al., 2020; Ferrón-Vílchez et al., 2020; Gatti et al., 2021). Further, a number of scholars (e.g., Seele and Gatti, 2017) pointed out that greenwashing should, by definition, be linked to an explicit accusation coming from the media, the stakeholders, and society. Then, an accusation would be a crucial determinant of greenwashing.

In that sense, greenwashing depends on both a company-related factor, identified by the level of misleading information that the firm provides, and on a relational factor, represented by the accusation that results from the stakeholders’ perception of the misleading intention.

The analysis of greenwashing conceptualization that we have developed leads to a structuring of this theorization that aims to provide a concept that allows us to define an inclusive and complete overall vision of a multifaceted umbrella concept (Cooper et al., 2018; Roulet & Touboul, 2015).

To frame the concept of greenwashing, scholars have identified several cornerstones of its definition (e.g., Bowen, 2014; Seele and Gatti, 2017a, b; Ferrón-Vílchez et al., 2020). Following Delmas and Burbano (2011), greenwashing results from simultaneous bad environmental performance and positive environmental disclosure. However, in a further step, scholars identified the following three propositions as determinants (Bowen & Aragon-Correa, 2014): (1) corporate disclosure is selective, (2) greenwashing is a deliberate behavior (Mitchell & Ramey, 2011), which therefore determines an intentional deceit for stakeholders (Nyilasy et al., 2014), and (3) greenwashing starts from the willingness of the company that manages this strategy. Subsequently, we identify another crucial determinant of greenwashing: how the stakeholders perceive it (Seele & Gatti, 2017a, b). This aspect not only allows us to go beyond the company’s behavior, shedding light on the external environment’s active role in identifying the extent of the greenwashing effect, but also, at the same time, in identifying its motivations. According toSeele and Gatti (2017a, b), greenwashing occurs if disclosure is misleading and if stakeholders accuse the company of being deceptive. The above pillars of greenwashing explain a number of crucial aspects to be investigated with a view to managing environment-focused research.

First, disclosure is considered the main tool in realizing greenwashing strategies on which companies deliberate and that they manage. Further, as Seele and Gatti (2017) highlighted, greenwashing implies two perspectives for observing the phenomenon. The first perspective is related to the information that a company would like to disclose, and to the extent of the disclosure’s potential misleading effect. The second perspective is related to the external perception of this information that could result in an accusation of falsity or omission.

The above considerations deserve further clarification. As highlighted, greenwashing is a strategy based on a company’s relationship with its stakeholders. However, Ferrón-Vílchez et al. (2020) point out that greenwashing does not in every case stem from a company initiative, and they elucidate the role of the large set of stakeholders that are interested in companies’ environmental responsibility, i.e., in their compliance with the legal obligations or the need to achieve environmental certifications (Sutantoputra, 2022). In that perspective, greenwashing can be interpreted not only as a strategy pushed by companies but also as an effect pulled by stakeholders. Consistent with this second view, Ferrón-Vílchez et al. (2020, p. 862) define greenwashing as “a group of symbolic environmental practices born in response to the stakeholders’ pressures.”

Different levels of greenwashing actions stem from the above definition. In a first step, scholars (e.g., Delmas & Burbano, 2011) defined two greenwashing levels (Yu et al., 2020; Zharfpeykan, 2021) and in a further development of the analysis, Torelli et al. (2020) added two more levels. Company-level greenwashing is grounded in symbolic (Wong et al., 2014), selective, or misleading (Torelli et al., 2020) environmental disclosure, regarding the company’s mission, its certification, and other corporate-related issues capable of influencing its reputation. When the misleading “green communication” relates to the firms’ intentions for future strategies, the level of greenwashing is defined as strategic and can consist of disclosing the long-to-medium term objectives regarding the environmental aspects of the company’s activities. Some scholars (Torelli et al., 2020) also identified a dark level of greenwashing, which occurs when misleading or selective (Marquis et al., 2016) environmental disclosure aims to conceal illegal behavior. In our opinion, this form of communication could be applicable in all levels of greenwashing, when the company aims to hide illegal actions that enable several strategic or operational activities. Finally, product-level greenwashing relates to the information that a company discloses to promote its products and their environmental peculiarities. Product-level greenwashing occurs when this information is not fully truthful or complete (Delmas & Burbano, 2011).

The above considerations suggest that greenwashing can be viewed as a deliberate strategy (Seele & Schultz, 2022) involving different aspects of the companies’ activity. The deliberate strategy is realized through using different kinds of corporate disclosure (selective, misleading, false, and so on) or through actions that aim to enhance symbolic disclosure or to divert attention (Gatti et al., 2021). Further, among other things, the deliberate strategy aims to improve or repair the company’s reputation and image as perceived by stakeholders (Bowen & Aragon-Correa, 2014; Delmas & Burbano, 2011; Ferron-Vilchez et al., 2020). The objective is to obscure illegal actions or corporate scandals (Torelli et al., 2020) or to foster financial and market performances and companies’ valuations (Yu et al., 2020; Montero-Navarro et al., 2021) (Fig. 2). However, scholars explain that external stakeholders can become aware of greenwashing strategies, thus generating skepticism and undermining the company’s reputation (Bowen & Aragon-Correa, 2014).

5 In search of an explanation for greenwashing: what theories do scholars recall?

An observation of the greenwashing drivers is not fully possible without considering both the theories supporting and explaining these firms’ behaviors and the role of non-financial disclosure as the main tool that companies use to realize the above strategies (Seele & Schultz, 2022). In recognizing the main theories that support the greenwashing studies we aim to define a conceptual structuring capable of explaining firms’ motivations and behaviors, and of supporting greenwashing research.

In business economics studies, theories arise from several disciplines belonging to the social sciences. They help us not only to understand particular human and corporate behaviors but also to define the framework for studying such behaviors.

Several scholars (Walker & Wan, 2012; Laufer, 2003; Zharfpeykan, 2021; Seele & Gatti, 2017; Uyar et al., 2020; Ferrón-Vílchez et al., 2020; Dye et al., 2021; Mitchel & Ramey, 2011) have defined a theoretical framework for understanding greenwashing. These frameworks include, among other things, legitimacy (Oliver, 1991), signaling theory, stakeholder theory, competitive altruism theory (Barclay, 2004; Hardy & Van Vugt, 2006), and discretionary disclosure theory (Verrecchia, 1983) (Table 3).

5.1 The legitimacy theory

Legitimacy theory (Deegan et al., 2002) is grounded in the concept of legitimacy (Cuganesan et al., 2007) that, in a broad definition, can be viewed as “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (Suchman, 1995, p. 574). Walker and Wan (2012) explain that legitimacy stems from the assumption that the socially accepted rules or values represent the setting in which corporate behaviors should be considered appropriate (Suchman, 1995) from the perspective or judgement of this social setting’s actors (Bitektine, 2011). In other words, legitimacy theory, that belongs to the macro‑level theories (Seele & Shultz, 2022), defines a contract between the company and its stakeholders (Deegan et al., 2002; Deegan & Unerman, 2011; Gatti et al., 2021). On the one hand, the contract requires companies to behave properly, and, on the other hand, it legitimates those companies that appear to be compliant with formal or informal social rules (Zharfpeykan, 2021). In this regard, Roberts (1992) considers legitimacy not only as a tool to improve financial or social performance (Deephouse, 1999) and companies’ value but also as a survival condition. In fact, stakeholders’ legitimation gives companies greater opportunity to obtain resources and financing, and it facilitates the relationships in the competitive system (Walker & Wan, 2012; Seele & Gatti, 2017).

Since CSR initiatives, including companies’ environmental efforts, should be considered as new legitimacy determinants (Seele & Gatti, 2017; Berrone et al., 2017; Hahn & Lulfs, 2014), the greenwashing strategies can be framed within legitimacy theory as a form of seeking legitimation which they found on misleading disclosure (Velte, 2022; Lee & Raschke, 2023; Li et al., 2023).

Legitimacy studies (Scherer et al., 2013; Bitektine, 2011; Suchman, 1995) identify several types of legitimacy. Among the different interpretations, we briefly mention three possible classifications and aspects that can help to interpret the phenomenon of greenwashing (Bowen, 2019; Seele & Gatti, 2017). Suchman (1995) defined cognitive legitimacy, pragmatic legitimacy, and moral legitimacy (Seele & Lock, 2015). Cognitive legitimacy occurs when environmental culture is taken for granted. Moral legitimacy stems from normative approval (Zyglidopoulos, 2003) and is related to how a society evaluates the company’s behavior (Bitektine, 2011). Pragmatic legitimacy is based on self-interest evaluations of the company’s stakeholders and on their perceptions of the advantages they can gain from firm activities (Seele & Gatti, 2017; Shuman, 1995).

Further, legitimacy has been classified as internal if it concerns a company’s insiders, or external if it concerns an external audience (Bitektine, 2011; Kostova & Roth, 2002). In a greenwashing analysis, an external perspective of legitimacy would be more useful than an internal one.

Adopting the legitimacy theory lens to analyze greenwashing as previously defined, implies a focus on pragmatic legitimacy. This is consistent with Seele and Gatti’s (2017) analytic framework, which links research on pragmatic legitimacy to the intentional misleading scope of green disclosure and adopts a strategic approach (Scherer et al., 2013) to legitimacy (Pfeffer, 1981). Following the framework given above, Seele and Gatti (2017) recognized that disclosure regarding green and environmental issues is a strategy aimed at gaining and improving legitimacy (Cho et al., 2022) or at reconstituting a compromised legitimacy (Laufer, 2003; Deegan et al., 2002). The strategic approach considers legitimacy as an operational resource that companies obtain from the cultural setting in which they operate (Suchman, 1995). In this theoretical framework, greenwashing consists of a legitimation strategy, adopting environmental disclosure to “legitimate social and environmental values which may or may not be substantiated” (Mahoney et al., 2013, p. 352).

Legitimacy is also interpreted in institutional studies (Suchman, 1995), which consider it as a set of “constitutive beliefs” (Suchman, 1988). In this perspective, legitimacy is not regarded as a resource extracted from the social environment but as something that arises from an external institution’s construct (Suchman, 1995). As Bowen (2019) states, an institutional approach suggests that the companies’ behaviors aim to reach social approval. Also, the change observed in the stakeholders’ expectations pushes companies to adapt their strategy and their disclosure to comply with current societal expectations (Cuganesan et al., 2007). In that sense, the increased consciousness of environmental issues and the related disclosure can be considered as a form of adapting the company’s behavior to comply with the perceptions and expectations the social system’s actors have (Hahn & Lulfs, 2014). Research framed in an institutional theory perspective, sheds light on the relevant role of the social environmental context, such as norms, regulations and cognitive factors, which influence companies’ organizational practices (Delmas & Burbano, 2011). The role of the regulatory context as a greenwashing driver should to be seen in association with the other external factors and internal conditions, so that we can define their behavior as an adaptation prompted by all these factors’ pressure. This point of view, which is related to organizational institutionalism, adds a meso-level perspective of investigation to the theoretical background (Seele & Shultz, 2022).

5.2 The stakeholder theory

In the same way as legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1994) is another socio-political theory (Gray et al., 1995; Uyar et al., 2020) scholars have adopted to explain greenwashing practices (Velte, 2022). Stakeholder theory refers to the concept of stakeholder engagement, defined by Sharma and Vrendenburg (1998) as “the ability to establish trust-based collaborative relationships with a wide variety of stakeholders” (p. 735). Stakeholder theory indicates that the stakeholders’ involvement in the companies’ decisions has a dual purpose. The first is to fulfill the ethical requirements in accordance with the societal norms, and the second is to strategically manage the relational capital (Edvinson & Malone, 1997; Stewart, 1997). Both these purposes are instrumental in achieving a competitive advantage (Cennamo et al., 2009; Seele & Shultz, 2022).

The stakeholders’ engagement (Sacconi, 2006) assists in overcoming the financial performance’s boundaries to include the achievement of social performance. In that sense, accountability includes both kinds of performance (Guthrie et al., 2004), extending the concept of financial value toward that of social value (Dumay, 2016).

Corporate environmental performance fits in the perspectives of both the legitimacy theory and the stakeholder theory, because the societal expectations about the “green behavior” of a company increase over time and encourage firms to reach legitimacy and satisfy the stakeholders’ requirements. Environmental efforts may therefore also be considered as a company’s adaptive behavior to fulfill the above-mentioned requirements and toward the stakeholder pressure (Ferrón-Vílchez et al., 2020; Murillo-Luna et al., 2008). Since external pressure is considered to be the most effective driver of an environmental commitment (Seele & Schultz, 2022; Velte, 2022), it may be difficult to discern whether the real determinant of companies’ green efforts is a moral attitude or a reaction to the stakeholders’ pressure (Crifo & Sinclair-Desgagné, 2013).

5.3 The signaling theory and a glance at other theories

The signaling theory, which is widely used to explain greenwashing strategies, also emphasizes the crucial role of disclosure. Drawing on voluntary disclosure theory (Clarkson et al., 2008), signaling theory (Mahoney et al., 2013) explains that, since corporate disclosure reduces information asymmetries (Berrone et al., 2017), it can contribute to increase corporate valuations, considered both in a financial and in a social meaning (Michelon & Parbonetti, 2012; Dumay, 2016). In fact, disclosure regarding environmental responsibility is a signal of companies’ commitment to these issues, which makes stakeholders aware that the company’s behavior is congruent with their expectations. However, in the case of greenwashing, the signaling power of the voluntary disclosure stems from information asymmetries.

Seele and Gatti (2017) favor signaling theory to explain greenwashing, because signaling theory makes it possible to observe both how the message is sent and how it is received and interpreted, in the presence of information asymmetries. In that perspective, Seele and Gatti motivate why misleading “green disclosure,” formulated to show a commitment to environmental issues, can (falsely) “signal” corporates’ positive social values (Connelly et al., 2011). They assume that disclosing positive information regarding green behaviors is convenient for both good and bad environmental performers. In a signaling theory perspective, every company can choose whether to disclose or not disclose truthful information about its “green” performance (Connelly et al., 2011; Yekini & Jallow, 2012). Taking this into account, that companies are keen to gain legitimacy (Lee & Raschke, 2023) represents a strong incentive for bad environmental performers that can use information asymmetries to signal a misleading message in terms of good environmental behaviors, thus acting as greenwashers. According to signaling theory, companies with superior environmental performance show a higher propensity to voluntarily divulge that environmental behavior, when compared to bad performers (Mahoney et al., 2013). Signaling theory differs from legitimacy and stakeholders’ theories in this sense, because stakeholders assume that disclosure can be used as a tool to realize greenwashing strategies (Hahn & Lülfs, 2014).

Nevertheless, signaling theory, consistent with a voluntary disclosure perspective (Mahoney et al., 2013), is grounded in the reduction of information asymmetries, and scholars believe that external stakeholders do not have the tools to distinguish between true or false information regarding environmental issues (Carlson et al., 1993). In such a context, information asymmetries between firms and stakeholders allow greenwashers to signal a positive image of their company (Li et al., 2023), thus improving the company’s reputation. Further, legitimacy and stakeholder theories suggest that external stakeholders’ pressure induces bad environmental performers to produce voluntary disclosure regarding “green behaviors” (Patten, 2002; Uyar et al., 2020).

Other scholars have used the competitive altruism theory to explain greenwashing (Barclay, 2004; Hardy & Van Vugt, 2006; Mitchel & Ramey, 2011). According to this theory, companies (as well as individuals) compete to be considered altruistic, because conveying an image of altruism to outsiders strengthens a reputation of trustworthiness.

Additionally, prior literature gives the agency theory perspective (Jensen & Meckling, 1976) in attempting to explain the behaviors of individuals at a micro-level (Seele & Shultz, 2022). This perspective opens up a space for research that investigates greenwashing as a corporate governance issue.

Following the first perspective of agency theory that focuses on the owner-manager relations, greenwashing can be analyzed as a tool to promote managers’ interests to the detriment of the shareholders and, in this peculiar case, it also harms other social actors. In this sense, greenwashing could be investigated as a management tool for pursuing self-interest objectives. Greenwashing, as mentioned, is a strategy based on information asymmetries (Lee & Raschke, 2023), which are capable of generating agency costs (Ashbaugh et al., 2004). It draws attention to the need for a higher level of control on managers’ activities.

Following the second perspective of agency theory regarding control of the owner-minority relations, especially in case of a high concentration of shares, it can be studied as an entrenchment effect output (Bennedsen & Nielsen, 2010), where shareholders and managers adopt opportunistic behaviors to the detriment of minorities (Claessens et al., 2002). In such cases, the assignment to control should be delegated to the so called “external watchdogs” (Seele & Shultze, 2022).

5.4 Conceptual organization of the main theories

Disseminating information regarding green activities is considered a way to enhance corporate reputation (Seele & Gatti, 2017; Baum, 2012), as well as to enhance revenue and other kinds of financial performance (Deephouse, 1999). The search for external legitimacy within a pragmatic approach and stakeholder pressure for compliance with environmental issues (Ferrón-Vílchez et al., 2020) could, however, lead companies to use disclosure to gain both legitimacy and stakeholders engagement.

The legitimacy theory perspective (Deegan et al., 2002) considers disclosure as a tool for improving the stakeholders’ accountability and reputation (Macias & Farfan-Lievano, 2017). Consistently, voluntary “green disclosure” is considered an instrument to engage salient stakeholders by reporting content that is congruent with their values and expectations (Dye et al., 2021; Mahoney et al., 2013). As Seele and Gatti (2017) stated, the role of disclosure becomes especially crucial when environmental scandals occur and companies have to repair their image and rebuild trust in corporate behaviors.

The search for pragmatic legitimacy, as well as stakeholder pressure (Gray et al., 1995), can bring about strategic uses of disclosure, which impact stakeholders’ perception and generate information asymmetries. This happens with greenwashing, as it is a phenomenon that can be interpreted in a socio-political theoretical perspective, to which legitimacy and stakeholder theories belong (Deegan et al., 2002). In fact, legitimacy theory justifies such communication habits, since symbolic, selective, misleading, or false disclosure is useful in concealing events that could threaten corporate legitimacy or in concealing bad environmental events with misleading or symbolic information (Zharfpeykan, 2021). Stakeholder theorists (e.g., Ferrón-Vílchez et al., 2020) explain the use of misleading disclosure regarding green actions by viewing it as an answer to stakeholders’ need to be involved in and informed about the companies’ activities and, at the same time, as a tool to manage stakeholders as a strategic resource (Cennamo et al., 2009).

The motivation to implement greenwashing policies also depends on the features of the institutional context in which companies operate, such as the pollution sensitivity, the sector (De Vries et al., 2015; Delmas & Burbano, 2011), the legislative measures, and the legal enforcement in the context of a particular country. More stringent regulations regarding environmental behaviors result in stronger pressure on companies (Kim & Lyon, 2015). The institutional context, seen both as a set of regulations and as a result of activist groups, is considered a variable capable of impacting greenwashing practices (Delmas & Montes-Sancho, 2010; Marquis et al., 2016).

In the above-mentioned conceptual framework, Ferrón-Vílchez et al. (2020) identify both a proactive and a reactive motivation for greenwashing behaviors. These motivations arise from companies wanting legitimation or from a response to external pressure of stakeholders, that aim to generate an external image of the company that is better than the real one, improving the firm’s reputation and ultimately its competitive advantage (Velte, 2022; Lyon & Montgomery, 2015). This information confirms the pivotal role of disclosure. Disclosure represents an answer to the stakeholders’ need to be informed about corporate activities (Ullmann, 1985), with the intent of reducing information asymmetries. At the same time, disclosure represents a legitimation strategy (Deegan et al., 2002). In fact, misleading disclosure deliberately generates information asymmetries to induce a positive shareholder perception and to preserve legitimacy (Uyar et al., 2020).

The above theories anticipate that stakeholders will punish companies that exhibit bad environmental behavior and, at the same time, they state that disclosing information is costly (Mahoney et al., 2013; Uyar et al., 2020). In fact, the discretionary disclosure theory (Verrecchia, 1983) underscores that, since disclosure comes at a price, managers select the information that should be disclosed. Verrecchia (1983) also states that the undisclosed information can be interpreted in several ways. This suggests that the external stakeholders are, in any case, not able to attribute a negative connotation to the withheld information and, consequently, cannot discount the company value.

The above considerations explain that the conceptualization of greenwashing that emerges via the theories systematically converges toward a consideration of disclosure, offered through several tools, as a key resource in understanding the greenwashing strategy. This strategy aims to generate an external image of the company that is better than the reality, improving the firm’s reputation and ultimately its competitive advantage (Table 4).

6 Proposing a framework for analyzing greenwashing’s economic and social value relevance

Environmental issues are becoming increasingly relevant, therefore companies redefine their behaviors to comply with this crucial matter, also to fulfill an accountability function (Yu et al., 2020; Lashitew, 2021). However, green behaviors do not follow companies’ ethical values in every instance; they are also consequent to strategic decisions that aim to improve companies’ image and reputation through manipulating the corporate disclosure (Cho et al., 2022). We have emphasized the importance, as well as the difficulties, of a greenwashing conceptualization, to develop useful theorization of this issue and to provide tools for operationalizing the phenomenon through designing indicators that can be used in developing academic empirical research. Such indicators are also necessary for monitoring and limiting the greenwashing in which the authorities and regulators engage.

Since various theories have contributed to identify the possible motivations for doing greenwashing, it is now critically important also to observe the consequences of greenwashing behaviors (Berrone et al., 2017). This should help companies to rebuild their business model to comply with environmental objectives (Arena et al., 2022). This compliance effort would require adequate investments regarding the organizational, structural, and human perspective to accommodate the transversal nature of “greenization.” However, as stated, companies might report on their environmental involvement without really investing in the necessary underlying environmental strategies.

Companies’ commitment to environmental issues is widely recognized as a shareholder value driver and it is also identified as a social value driver (Michelon & Parbonetti, 2012). As explained above, reporting about companies’ environmental commitment reduces the information asymmetry between firms and stakeholders and contributes to legitimating firms’ behavior, positively affecting the companies’ value (e.g., Michelon & Parbonetti, 2012), in both its financial and social dimensions (Dumay, 2016). Greenwashing aims to pursue this objective unethically by disseminating misleading disclosure.

Thus far, the absence of an effective mandatory ESG reporting framework left room for manipulating the information that was voluntarily disclosed (Zharfpeykan, 2021). Manipulating the information generates information asymmetries that mislead the actors in the social and competitive system and help to achieve the above-mentioned goals, without the company acting as a “good citizen” (Mahoney et al., 2013). The potential benefits in terms of improvements in relational and reputational capital, in fund-raising, and in financial performance induce companies to show an environmental responsibility even if they are not environmentally committed (Siano et al., 2017).

Misleading disclosure enables legitimating corporate actions that are not good practice and do not truthfully reflect reality. Disclosure therefore assumes the two-fold role of seeking transparency to involve stakeholders in the company’s activities and of being a communication strategy aimed at establishing intangible resources, both useful in creating economic value.

6.1 The role of reputational and relational capital

Recent literature (e.g., Rabaya & Saleh, 2022) informs that reputational and relational capital are crucial economic drivers of a company’s value, especially in the current era where invisible assets become distinctive resources. In this sense, environmental disclosure is viewed as a useful instrument in building reputational and relational capital and, therefore, financial performance and competitive advantage (Cantele & Zardini, 2018). The link between disclosure, competitive advantage, and value becomes manifest in disclosure that has the ability to nourish invisible assets that, as mentioned, are often effective economic value drivers. Companies’ legitimation and stakeholders’ engagement facilitate the generation of reputational capital. Bitektine (2011, p. 160), in proposing a theoretical correlation between legitimacy and reputation, emphasizes a distinction between the two concepts: “This theorized correlation, however, should not be regarded as a lack of discriminant validity between the measures of the two concepts but, rather, as the effect of an overlap in criteria that evaluators use to make two fundamentally different forms of judgment.” Dollinger et al. (1997) concur with this view, identifying community and green responsibility as key dimensions of reputation.

Environmental disclosure, by strengthening the relational capital, is instrumental in ensuring legitimation. Nowadays, reporting environmentally responsible behaviors is considered a crucial determinant of improving the relations with stakeholders, the corporate reputation, and gaining a competitive advantage (Uyar et al., 2020; Rabaya & Saleh, 2022).

As Rabaya and Saleh (2022) explain, environmental commitment entails an improvement of financial performance, a reduction in cost of equity, and an improved credit rating (La Rosa et al., 2018). Both the improvement of financial performance and the reduction in cost of equity are value drivers that contribute positively to improve economic value for shareholders, which is the basis of expected future income and risk (Rappaport, 1986; Stewart, 1991). However, the above effects on corporate value can become concrete if stakeholders are aware of the poor environmental commitment. In this sense, environmental disclosure contributes to creating the relational capital strictly linked to the company’s reputation (De Castro et al., 2004) and, therefore, to a sustainable competitive advantage. Certain scholars (Cantele & Zardini, 2018) consider reputation to be a first intermediate objective and they view competitive advantage as a second intermediate goal of companies that are willing to ultimately increase financial performance through enhancing environmental responsibility. In other words, the link between accomplishing sustainability and improving financial performance is mediated, first, by reputation, among other determinants, and second, by the achievement of cost or revenue advantages.

Fombrun (1996, p. 11) defines reputational capital as “a form of intangible wealth that is closely related to what accountants call ‘goodwill’ and marketers term ‘brand equity.’” Reputation derives from stakeholders’ perception of a company that becomes clear in their reactions (Deephouse, 1999). Among the several drivers of reputation, social responsibility is considered not only one of those drivers, but in fact a prerequisite to reputation (Rettab et al., 2009; Cantele & Zardini, 2018). Since, as we previously reported, reputation assumes the strategic role of gaining a competitive advantage (De Castro et al., 2004), it represents one of the greatest opportunities for creating economic value. However, reputation is a fragile and scarce resource and it is highly dependent on the relation between the company and its external environment (Gatti et al., 2021): without credibility there is no reputational capital (Worden, 2003). This normative dimension of reputation, which relies on credibility, confirms its link with relational capital and recognizes the role of greenwashing as a value creation strategy. This viewpoint is consistent with the results of Cho et al. (2022) who highlight that reporting bad news also helps to generate the impression of company transparency and strengthens company credibility.

Even if environmental disclosure is considered an important tool for preventing reputational damage (Reber et al., 2022; Cooper et al., 2018), deceptively manipulating disclosure, a practice that characterizes the greenwashing strategies, can impact the reputational risk and generate reputational damage. Siano et al. (2017) proposed a concrete example of reputational damage arising from misleading reporting. This is illustrated in the so-called “Dieselgate” case (Gatzert, 2015), which suffered a significant reputational loss as a result of fraudulent behavior fostered by misleading corporate disclosure. Referring to this, Siano et al. (2017) clarify the key role of reputational capital in research that aims to investigate the greenwashing phenomenon. In fact, firm reputation can be seen as a “protection” against the possible market valuation of real environmental performance but, in a different perspective, reputational damage, depending on stakeholders’ awareness of the gap between the positive image that greenwashing generates and the real, less favorable, environmental commitment, may have a value destroying effect (Cooper et al., 2018).

Reputational capital is important, also to improve a company’s competitiveness in the financial markets, thereby boosting its capacity to gain access to financing resources, bearing lower costs than competing companies. As Mazzola et al. (2006) stated, a good reputation contributes to companies being considered an “investment choice.” In recent years, this possible impact of environmental responsibility on companies’ capacity to attract financing is demonstrated by the issuing of “green bonds” that, as the London Stock Exchange (2021, p. 2) states, are “any type of bond instrument where the proceeds will be exclusively applied to finance or re-finance in part or in full new and/or existing eligible ‘green’ projects.” As Dye et al. (2021) argue, nowadays environmental issues are variables with the ability to influence financing decisions, which obliges financial institutions to disclose information about their environmental impact. However, when reporting is unclear, the emerging information asymmetries can prejudice the decision process of a potential investor (Rabaya & Saleh, 2022). and if investors become aware of a firm’s misleading disclosure, the market responds to such greenwashing by producing negative abnormal returns and negative impacts on corporate financial performances (Testa et al., 2018a). Also, the market can detect whether a company is an “environmental wrongdoer” because environmental performance scores can reveal the gap between what is said and what has been done. Then, the market has the ability to punish such a trespassing firm (Du, 2015).

Further, a good reputation helps reduce market volatility and helps foster the management of potential corporate or environmental crises (Mazzola et al., 2006). For these reasons, reputational capital, among other things, should be considered an important value driver.

Reputational capital is related to various essential elements, such as relationships with stakeholders and communication, which influence people’s perceptions. Relational capital is a component of intellectual capital (Stewart, 1997). The concept of relational capital, theoretically supported by a resource-based view (Barney, 1991; Wernerfelt, 1984), stems from the value added by the relations between a company and the relevant environmental actors. Communication is a fundamental asset of relational capital, which – within the company – aims to manage and strengthen relationships with all stakeholders (Velte, 2022).

Value is a broad concept that goes beyond the boundaries of its financial dimension, involving a social perspective too (Dumay, 2016). In November 2020, the International Valuation Standard Council (IVSC, 2020, p. 4) stated that “‘Social Value’ includes the social benefits that flow to asset users (social investment) and the wider financial and non-financial impacts including the wellbeing of individuals and communities, social capital and the environment, that flow to non-asset users.” From the IVSC’s viewpoint, value is a wide concept, which includes three dimensions: the monetary benefit to the asset owner, the social benefit to asset users, and the social benefit to non-asset users (IVSC, 2022). The first component could be more strictly linked to a financial concept of value, while the second and the third components are included in the concept of social value.