Abstract

In the context of agricultural activity intensification and rural abandonment, neo-rurality has emerged as a back-to-the-land migratory movement led by urban populations seeking alternative ways of life close to nature. Although the initiatives of the new peasantry are diverse, most are land related, such as agriculture and livestock farming. A priori, neorural people undertake agri-food system activities in ways that differ from the conventional model, following the principles of environmental and social sustainability. We conducted a systematic review of the literature on the neo-rural phenomenon with the main objective of examining how neo-rurality has been found to support agroecological transitions. The corpus of neo-rural studies was analyzed from a social-ecological perspective, and a Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) was conducted to determine whether neo-rural agri-food system activities follow agroecological principles. The results indicate that neo-rural studies is an emerging research field that has received considerable attention in western countries. Diverse conceptualizations and terms have been used to address the phenomenon, but the literature agrees on political and environmental motivations and several barriers faced by neo-rural people. This population and in particular new peasants, are employing a wide variety of agroecological practices and strategies throughout the agri-food system. Overall, neo-rural people have been reported to contribute significantly to agroecological transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the last century, traditionally agrarian rural areas worldwide have experienced deep changes in demographics and human–nature relations. The prevailing urban-industrial development model, converging with the Green Revolution, resulted in two simultaneous and largely common trends. On one hand, the twentieth century saw the intensification and technification of agricultural productive activities in efforts to achieve maximum productivity using external inputs (Borlaug 1971; Bowler 1992). On the other hand, the deagrarization of rural areas due to the disappearance of considerable portions of small-scale farmers, together with large-scale urban industrialization, has promoted a rural exodus (Camarero 1993; Saville 2013; Baudin and Stelter 2022). This massive outmigration of people from rural areas to cities, which in Europe started between the 1950s and the 1970s and continues today, is one of the largest migratory movements in western countries’ histories (Camarero 1993).

The social-ecological consequences of these changes are multidimensional, encompassing ecological impacts such as landscape homogenization (Tilman 1999) and biodiversity (local breed and variety) loss, as well as negative impacts on ecosystem services such as water and soil pollution, soil erosion, and habitat fragmentation (Matson et al. 1997; Swinton et al. 2007). Demographic impacts include the depopulation of rural areas and the aging and masculinization of rural populations (Camarero 2017; Baudin and Stelter 2022). Economic consequences include the lack of generational replacement, dependence on global markets, deregulation, the strengthening of the tertiary sector, and the exploitation of rural areas for tourism and leisure activities (Bonanno 1994). Sociocultural impacts encompass the abandonment of local agricultural and livestock practices; the loss of local, traditional, and indigenous ecological knowledge (Aswani et al. 2018); the rupture of identity links with the land; changes in producer–consumer relations (Therond et al. 2017); and the devaluation of the peasantry. Policy-level effects include the bureaucratization of agricultural activities (FAO 2017; Lojka et al. 2021) and the application of health and hygiene regulations designed for large industries.

Agri-food system industrialization and globalization are responsible for a substantial share of current global environmental change (Tilman 1999; Bennett 2017). The main driver of this change is the current agricultural model, which negatively affects genetic diversity, freshwater use, land-use changes, and biogeochemical flows (Campbell et al. 2017). To mitigate these negative impacts, deep transformations are required, not only in the primary sector but throughout the agri-food system, including production, processing, and distribution (Ingram 2011; Springmann et al. 2018). Among alternatives for the mitigation of this social-ecological crisis, social movements and political paradigms such as agroecology, food sovereignty, and back-to-the-land movements (e.g., neo-rural and new peasantry paradigms) have emerged as resistance and contestation forces aiming to relocate and deeply transform agri-food systems to guarantee the right to food through socially and environmentally sustainable and just practices (Martinez-Torres and Rosset 2010; Altieri and Nicholls 2012; Forssell and Lankoski 2015; Gliessman 2018).

Agroecology has been articulated as a tripartite vision for practice, science, and social movement (Wezel et al. 2009). This interdisciplinary paradigm provides an ecological approach to land management (Wezel et al. 2014) that goes beyond a set of agricultural practices (LVC 2010) and cannot be separated from the political component of social critique (Sevilla Guzmán and Woodgate 2013; Márquez-Barrenechea et al. 2020). Agroecological transitions have been conceptualized as sets of changes and, overall, transformation from the conventional industrialized model to a sustainable agricultural model, with agri-food systems that foster the development and maintenance of resilient social-ecological systems (Ollivier et al. 2018).

The neo-rural phenomenon (Chevalier 1981; Nogué 1988), also called the back-to-the-land/countryside movement (Wilbur 2013), is an increasingly popular reverse-demographic trend of urban–rural migration. It originates in countercultural and hippie movements in Europe and North America in the second half of the twentieth century (Belasco 2007; Stuppia 2016; Toledo Machado 2024). The study of neo-rurality has expanded since its first definition in many disciplines and using different frameworks (Trimano 2019a), such as new rural (Camarero and Oliva 2016), amenity migration (Moss 2006; Abrams et al. 2012), counterurbanization (Ratier 2002), and back-to-the-land (Wilbur 2014a, b) movements. In most research, the phenomenon is equated to its protagonists’ roles, such as in profiles of neo-rural practitioners (Chevalier 1981; Nates and Raymond 2007; Rivera 2020; Karpinski 2020) and studies of their motivations and values (Bertuglia et al. 2013; Dopazo Gallego and De Marco Giachino 2014; Pinto-Correia et al. 2016) and the barriers that they face (EIP-AGRI 2016; Flament-Ortun et al. 2017). Researchers have not reached consensus on the extent of the concept or even who is neo-rural. Different classifications have been proposed to delimit the field, resulting in a diversity of terms such as “commuters,” “new peasants,” “retired people,” and even “neo-rurals separated from the land” (Ratier 2002; Ploeg 2010; Nogué 2016). The concept is difficult to define theoretically because it distorts the boundaries of the historical urban/rural dichotomy (Camarero and Oliva 2016), and practically because it has been argued to lose meaning when encompassing all rural return migration (Halfacree 2007). The provision of a historical perspective on the phenomenon and the disentangling of different conceptualizations in neo-rural studies are thus of interest.

In attempts to characterize neo-rural diversity, researchers have proposed the terms “new peasantry” (Van der Ploeg 2009; Monllor 2012), “new entrants into farming” (EIP-AGRI 2016), and “new farmers” (Mailfert 2007; Laforge et al. 2018) to describe those who focus their activities on the agri-food sector. These individuals are urban people who move to rural areas to work the land, such as by performing agricultural and livestock farming activities, seemingly in ways differing from those of the conventional agri-food model (Monllor and Fuller 2016). In their daily work, they may adopt practices and values of the agroecological paradigm (Rosset and Torres 2016), potentially contributing to the building of more sustainable agri-food systems.

However, the literature on neo-rurality and the new peasantry to date has barely addressed the nexus among neo-rural people, their activities, and the host territories, understood as social-ecological systems (Berkes and Folke 1998). The consideration of agroecosystems as social-ecological systems implies the adoption of a holistic vision that challenges the historical human/nature dichotomy, with the perspective that the coevolution of both has given rise to current cultural and rural landscapes (Berkes et al. 2000). A social-ecological perspective on this phenomenon could shed light on whether and how neo-rural and new peasantry movements are actually embodying the sustainable repopulation of rural areas and eventually promoting agroecological transitions of agri-food system toward food sovereignty.

The main goal of this review was to examine the literature on the ways in which the neo-rural phenomenon supports agroecological transitions. We analyzed the literature on neo-rurality and new peasantries using a social-ecological approach. In particular, we aimed: (1) to provide an historical perspective and characterize the geographical distribution of scientific studies on neo-rurality, new entrants into farming, and new peasantries; (2) to explore different conceptualizations and terminological nuances; (3) to systematize neo-rural individuals’ motivations, values, barriers, and difficulties; (4) to explore relationships of neo-rural individuals and new peasants to agroecological transition; and (5) to identify potential impacts of the neo-rural phenomenon on social-ecological systems. In this paper, we use the term “neo-rural” to refer to this concept most inclusively.

Theoretical frameworks for the exploration of linkages between the neo-rural phenomenon and agroecological transitions

We examined three theoretical frameworks for the exploration of relationships of the neo-rural phenomenon and new peasantry to agroecological transition and the identification of their potential impacts on social-ecological systems: one focused on agroecological transitions and two on how the new peasantry relates to ecosystems. Anderson et al.’s (2019) “transformation domains” framework encompasses six critical areas of practices and strategies that contribute to agroecological transformation from a multilevel perspective: access to natural ecosystems, knowledge and culture, systems of exchange, networks, discourse, and gender and equity (Table 1). It is useful for the characterization of agroecological transition as a process, and it enabled us to analyze the literature that relates this process to the neo-rural phenomenon. Second, in the context of “repeasantization”, Van der Ploeg and Roep (2003) proposed a framework for new rural development for agriculture in response to the modernization paradigm that has prevailed in agricultural development in recent decades. The authors define three rural development strategies for the diversification of the agricultural income base and encouragement of the transition to multifunctional agroecosystems in rural areas: deepening, broadening, and regrounding (Van der Ploeg and Roep 2003) (Table 1). Related to that framework and with the integration of insights from research on new ruralities and peasant agriculture, Monllor (2013) proposed an agrosocial framework for the conceptualization of agro-livestock practices and values being developed by new peasantries and their contributions to the transformation of the agri-food system. Monllor (2013) developed an agrosocial index with eight components: autonomy, cooperation, diversity, environment, innovation, local scale, slow focus, and social commitment (Table 1).

Alongside the transformation domains approach, which focuses on agroecological transition, the second and third frameworks incorporate the concept of the new peasantry and link it theoretically to specific agri-food system activities carried out by neo-rural individuals. Although we recognize the existence of other well-known frameworks for the analysis of agroecological practices (e.g., those proposed in FAO 2019; HLP 2019; Wezel et al. 2020), we argue that these three approaches together encompass most of the diversity of neo-rural land-related activities. Moreover, we find them to be optimal for the achievement of the main objective of the study, as they provide an overview of how new farmers relate to agri-food systems and, in particular, how they contribute to agroecological transition.

Materials and methods

Literature search

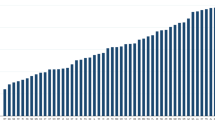

We conducted a review of the scientific literature (i.e., scientific papers, book chapters, PhD dissertations, and technical reports) published through the end of 2021 on the neo-rural phenomenon and the new peasantry. We adapted the PRISMA protocol (Page et al. 2021) and initially included only English- and Spanish-language publications, but later also incorporated publications in French and Portuguese to mitigate potential language bias. We initially (on 16 September 2021) searched the Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus databases using the keywords “neo-rural*,” "neorural*,” “neorrural*,” “new peasant*,” “neo-peasant*,” and “newcomer* into farming”. We retrieved 290 publications (151 from WoS, 139 from Scopus); we screened their titles, abstracts, and keywords, excluded 51 duplicates, and retained only those that were original research or reviews that discussed: (1) contemporary urban–rural migration, (2) the neo-rural/new peasantry phenomenon as the main or secondary theme, and/or (3) links between this phenomenon and agroecology and/or the food sovereignty movement. We read the complete texts of 115 selected publications and excluded another 21 that did not focus on the neo-rural/new peasantry phenomenon or urban–rural migration. We then expanded the database search using a snowball methodology adapted from Lecy and Beatty (2012), identifying studies cited in the selected publications that fulfilled the selection criteria. In this way, and due to the diverse, multidisciplinary nature of the object of study (Gretter et al. 2019), we included 42 more scientific papers and gray-literature items (i.e., newspaper articles and social movement writings). The final sample comprised 136 publications (Fig. 1; see Online Resource 1 for the complete list of included publications).

Data collection and analysis

Two databases were created for the mixed qualitative and quantitative analysis. An Excel 18.0 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) database was used to systematize information on the following variables for quantitative analysis: (1) publication characteristics (year, research type, spatial scale, geographical distribution, language, research discipline, publication type, methodological approach, inclusion of the term “agroecology” and a gender-focused perspective), (2) agri-food system activities, and (3) activity impacts on social-ecological systems. We further classified agri-food system activities according to the three conceptual frameworks (Table 1) to provide overviews of their involvement in agroecological transitions. As the term “agroecological practices” usually refers to farming and “agroecological strategies” usually refers to transformation and distribution tasks (Wezel et al. 2014; Agroecology Europe 2021), we use the term "agri-food system activities" to refer to an umbrella concept encompassing all actions that neo-rural individuals take at the agri-food system level. This approach enables us to not overlook activities that have not been classified as practices or strategies and that are based on neo-rural motivations and values (e.g., bartering and self-management). We calculated descriptive statistics for the first set of variables and determined the frequencies of mentions activities falling into the different framework categories. To explore relationships between the activities and framework domains (Anderson et al. 2019), strategies (Van der Ploeg and Roep 2003), and components (Monllor 2013), we performed a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) with the XLSTAT software (2023). We also quantified the co-occurrence of mentions of agri-food system activities and social-ecological impacts.

We used an NVivo 12 (Lumiero, QRS International) database created using a previously developed coding scheme (Online Resource 2) for the analysis of the included publications’ content. Inductive and deductive coding was performed until an accurate code list was created. Impacts were classified into five categories: (1) socio-economic, (2) demographic, (3) socio-political, (4) ecological, (5) and philosophical/symbolic.

Results

History and geographical distribution of scientific studies on the neo-rural phenomenon, new entrants into farming and new peasantries

Most (80%) of the publications appeared in the last decade (Fig. 2b). In the international databases considered, "neo-rural" first appeared in Garcia (1977), accompanied by the first theoretical conceptualization of the topic. Most [n = 84 (61%)] studies in the sample were performed in Europe, followed by South America [n = 26 (15.4%)]. We found no publication related to Africa or Oceania, and 20 (14.7%) publications were theoretical and had no geographic focus (Fig. 2a).

Most publications were scientific papers (76.5%; Fig. 3a) describing studies with exclusively qualitative designs (79.4%; Fig. 3b), most commonly involving semi-structured interviews. Case studies comprised 77.2% of the sample, and 41.2% of these publications included theoretical reflections (Fig. 3c). The most common scales were local (29%) and national (22%; Fig. 3d), and the most common publication languages were Spanish (48.5%) and English (39.7%; Fig. 3e). The most interest in the neo-rural phenomenon was in the social sciences and humanities (62.5%), followed by rural studies (12.5%) and the gray literature (9.6%), including publications by social movements and neo-rural collectives (Fig. 3f). More than half (68%) of the studies examined agroecological strategies and practices, but the term “agroecology” was used in only 41 (30%) publications (Fig. 3g).

Less than one-quarter (23.5%) of the publications contained reporting by gender; women were referred to most commonly in descriptions of back-to-the-land demographics and data collection. Most of the reviewed works did not describe the adoption of a gender-based approach; 21 publications described barriers that neo-rural women faced (Fig. 3h).

Differences in conceptualization and terminological nuances

The neo-rural phenomenon has been conceptualized in western academia as part of “new ruralities” (Ratier 2002) and “new rural movements” (Camarero and Oliva 2016), with social and geographical fuzziness of urban/rural boundaries. Different social profiles, motivations for migration, and process types underlie the use of different terms within the larger concept of neo-rurality. For instance, participants in back-to-the-land movements (migrants from cities to the countryside) have been referred to as “hippies” (Trimano 2015, 2019a; Morales 2016), “new pioneers” (Jacob 1997), “outsiders” (Cáceres-Feria and Ballesteros 2017; Dal Bello et al. 2022a, b), “back-to-the-landers” (Wilbur 2014a, b), “new peasants” (Ploeg 2010; Corrado 2010) and “newcomers into farming” (Monllor 2012). Motivations underlying such movements have been characterized as “amenity migration” (Moss 2006 in Quirós 2019), entailing natural or cultural leisure purposes; “pro-rural migration” (Halfacree and Rivera 2012), involving permanent relocation, predominantly in the global north; “counter-urbanization” (Ratier 2002), entailing former city dwellers’ maintenance of their urban occupations in rural areas; a “return to the countryside” (Nates and Raymond 2007), focusing on urban way of life enjoying the benefits of the countryside; a “return to the land” (Nates and Raymond 2007), focusing on the adoption of a neo-peasant lifestyle in balance with the environment; and “repeasantization” (Van der Ploeg 2009), referring to the transformation of conventional farmers into peasants and their struggle for self-sufficiency and subsistence in the context of deprivation and dependence. Descriptions of processes and settings in which the neo-rural phenomenon has manifested are also diverse, including mention of the migration of couples and families (Aguilar 2003a, b), community living (Castaño et al. 2020), ecovillage (Renau 2018; Ruiz Escudero 2019), rural squatting (Ruiz de Lobera 2018; Barbeta 2020), and the repopulation of abandoned villages (Gómez-Ullate 2004; Artiborain n.d.). Despite this diversity, the literature reviewed seems to show agreement that neo-rural populations are characterized by the greater presence of women and young, well-educated, and wealthy people relative to those following the conventional agri-food model (Chevalier 1981; Muzlera 2019; Monllor 2012; Rivera 2020).

Conceptualization of relationships of neo-rural individuals and the new peasantry to agri-food activities

Although “rural” tends to be associated with the land and natural resource management practices, terminology and theorizing about relationships between neo-rural individuals and the territories that they inhabit are diverse. Since the emergence of neo-rural studies, agricultural and livestock activity components have been examined (Chevalier 1981). The objects of study have expanded to include all types of people who move to the countryside from cities to start life projects and those who maintain close connections with urban environments (e.g., though telework and/or commuting to cities for work or leisure) (Nogué 2016). The conceptualization of the relationship between neo-rurality as a socio-demographic migration phenomenon and ties to the land and the agri-food system has been and remains subject to debate. Some authors have proposed adherence to the initial definition of neo-rural individuals as people of urban origin who perform land-associated rural activities (Giuliani 1990), whereas others have advocated for the consideration of individuals not associated with agri-food activities as neo-rural (Nogué 2016) or have proposed new categories such as “landless neo-rural” and “veteran neo-rural” (Ratier 2002). In the French school of geography, the term “new peasantry” was coined from néo-paysan (Chevalier 1981) to refer to people who move to the countryside to start production activities linked to the land with the aim of developing socially and environmentally fair agri-food systems (Nogué 2016; Milone and Ventura 2019; Castaño et al. 2020). In the North American literature, this concept has been expanded upon within the framework of new social and peasant movements, with the introduction of the term “new farmers” (Wilbur 2014a, b; Laforge et al. 2018; Xie 2021) and the less ambiguous term “neo-farmers” to distinguish those without a farming background (Mailfert 2007). The term "peasant" refers to the vocation that aims to recover agrarian practices that are part of traditional ecological knowledge and pre-industrial land management based on subsistence and local markets. Along similar lines, Van der Ploeg (2010) defined the new peasantry as a group of fundamental actors in the process of repeasantization and the generation of autonomy against agribusiness through agroecology. A similar concept appears in the Spanish literature, with the use of the terms “jove pagesia” and new “Baserritarras" in publications describing studies conducted in Catalonia (Monllor 2012) and the Basque Country (Calvário 2017), respectively. New peasantries have been classified according to productive activities and the degree of dedication (Castaño et al. 2020). In the South American literature, the term “new peasantry” refers not to a type of urban–rural migration, but to the political protagonists of the new peasant movements and the struggle to gain sovereignty for indigenous peoples (Veltmeyer 1997; Rosset and Torres 2016; Van den Berg et al. 2018).

Neo-rural motivations, values, barriers, and difficulties

Motivations and values underlying neo-rurality

The motivations and values underlying neo-rural individuals’ migration to the countryside appeared as a main or secondary theme in all studies reviewed. Neo-rural worldviews and values related to environmental, pro-decrecentist, and feminist activism are often part of the definition of the phenomenon and the drivers of migration (Bertuglia et al. 2013; Baylina 2019; Miguel Alonso 2019). For this reason, neo-rurality has been called "amenity migration" to reflect the leaving of cities in search of a better quality of life and connection to nature, rather than out of necessity (Moss 2006 in Quirós 2019). Despite its diversity and evolution, the neo-rural vision is based on the countercultural and hippie movements of the twentieth century (Toledo Machado 2024). Nature is understood as the ideal place for self-realization, the cultivation of personal relationships, slowing of the pace of life, and raising of children (Rivera and Mormont 2006; Álvarez 2013; Bertuglia et al. 2013). This perspective encompasses the essentialism of nature and rejection of the opposite, the city as “otherness,” materialized as urban pollution, rushing, noise, and consumerism (Mercier and Simona 1983; Álvarez 2013). Thus, neo-rurality has also been characterized as "utopian migration" due to its idealized vision of rural areas that often does not correspond to reality (Nogué 1988).

Despite the mention of socio-economic motivations such as starting a new job or lifestyle, philosophical and environmental motivations are most frequently mentioned in the literature. For new peasants, the construction of "peasantry" is understood as antagonistic to capitalism and part of one’s political-ideological values (Hajdu and Mamonova 2020), and the building of an alternative agri-food system through agroecology is a major motivation, even if not the only one (Monllor i Rico and Fuller 2016).

Barriers and difficulties associated with neo-rural migration

This topic is one of the most thoroughly studied, as reflected in the literature. The main barriers mentioned are at the societal level and related to adaptation to new places of residence (AEI-AGRI 2016), such as limited access to housing, the lack of support from institutions, lack of understanding from local populations, poor infrastructure (more acute in isolated areas), and language problems for foreigners. The most frequently reported barriers for new farmers are access to land and excessive bureaucracy (Flament-Ortun et al. 2017; Rivera 2020). Neo-rural individuals who adopted squatting as a political strategy for rural repopulation experienced many administrative problems and frequent eviction (de Bustillo 2017). On the other hand, European regulations and the common agricultural policy, which prioritize the market economy, force the regularization of local and traditional practices that are not included in formal legislative frameworks and hinder components of community and autonomous governance models, such as self-management, bartering, and seed exchange (Castaño et al. 2020; Cazella 2001). The barriers that neo-rural people face at the sectoral level are the lack of specific knowledge (Renau 2018), profitability, and access to economic capital (Monllor i Rico and Fuller 2016). In addition, neo-rural women face several gender-specific barriers, such as undervaluation, paternalism, and difficult work–family balance (Dopazo Gallego and De Marco Giachino 2014; Nigh and González Cabañas 2015; Samak 2017). Barriers may generate mismatches between expectations and reality, causing many neo-rural initiatives to fail (Rodríguez Eguizabal and Trabada Crende 1991).

Relationships between neo-rural and local inhabitants

Although relations between neo-rural and other inhabitants, referred to as locals or natives, are frequently discussed in the literature on barriers and difficulties associated with neo-rural migration, we discuss them separately due to their diversity and complexity. They range from suspicion, conflict, and lack of understanding to mutual support, cooperation, and welcoming (Aguilar 2003a, b; Mailfert 2007; Cortes-Vazquez 2014) and vary according to economic, sociocultural, political, and environmental factors (Willis and Campbell 2004; Simard et al. 2018). This diversity is due to differences in sociocultural trajectories, values, and power inequality between actors, as well as the social-ecological histories of the host territories (Trimano 2015). These differences frequently cause locals to feel invaded and see their traditions as being in danger; neo-rural inhabitants encounter a lack of support, hostility, and rejection from their neighbors, who consider them to be strangers or hippies (Ruiz Escudero 2012; Stuppia 2016). Conflicts with locals directly influence new peasants’ access to land and traditional ecological knowledge (Mailfert 2007; Gretter et al. 2019). Although this factor poses one of the stronger initial barriers for neo-rural people, living together, sharing, and meeting in common spaces (e.g., schools, markets, local festivals) promote relationships of trust and mutual support (García-Fernández 2020; Rivera 2020). However, the building of strong ties between neo-rural and local inhabitants is considered to be difficult and slow (Mailfert 2007).

Relationships of neo-rural people and new peasants to agroecological transition

Although at least one agroecological activity was mentioned in most (75.7%) publications reviewed, the agroecological framework was explicitly adopted in few studies (Dourian 2021). A total of 110 activities, practices, and agroecological strategies were identified (Online Resource 3) and grouped into 60 categories to facilitate subsequent analysis; those mentioned in fewer than 5 publications were disregarded. Most (47%) belonged to the production sector, followed by governance (19%) and the transformation and distribution sectors (15% each; Fig. 4a). The most frequently reported primary-sector activities were horticulture, extensive livestock (particularly sheep and goat) farming, the conservation and breeding of traditional breeds and landraces, small-scale production, diversification of activities, and the recovery of traditional knowledge and its integration with technical innovations. Artisanal agri-food production was a frequently mentioned secondary-sector activity, and local direct sales and attention to producer–consumer connections were frequently mentioned third-sector components. Collaboration and social participation (e.g., in cooperatives and associations) were the most frequently mentioned governance-level components.

In agreement with Anderson et al. (2019), most reported activities fell in the domain of access to natural ecosystems (48%), and practices related to the equity domain were described least frequently. According to Ploeg and Roep´s (2003) definition of new rural development for repeasantization, 26 activities corresponded to deepening and 31 each corresponded to broadening and regrounding. Diversity and environment were the agrosocial paradigm (Monllor 2013) components most closely associated with the activities identified, although all 8 components were associated with at least 30 agroecological activities (Fig. 4, Online Resource 3).

Using an MCA, we explored how these activities, a priori non-agroecological, were reported to be linked to or to follow agroecological logic, and thus how they are meant to contribute to agroecological transition according to the theoretical frameworks used. The MCA yielded four clusters. The first two axes explained 33.41% of the variance (Fig. 5, Online Resource 4). The first axis revealed a separation between productive agroecological practices related to the primary sector (negative side) and agroecological activities related to the distribution sector and governance (positive side). On the second axis, distribution activities related to the deepening strategy were on the positive side and networks related to cooperation were on the negative side.

Scatter plot of the first two axes from the multiple correspondence analysis of the agroecological activities performed by the new peasantry, representing agri-food sectors (AS, green), transformation domains (TD, yellow), strategies for new rural development (SD, blue), and agrosocial components (AC, purple)

The first cluster of agroecological activities was defined by the productive sector, access to natural ecosystem domains, deepening strategies, and the environment, and included small-scale production and the conservation and breeding of local landraces and breeds. The second cluster was related to the transformation sector, the deepening strategy, diversity, and slow focus, and included artisanal production and the recovery of traditional techniques. The third cluster was related to the distribution sector, exchange systems, knowledge and culture domains, local scale, autonomy, and innovation, and included certification and labeling and direct local sales. The fourth cluster was related to the governance level, equity, networks and discourse domains, the broadening strategy, social commitment, and cooperation, and included participation in agri-food cooperatives and price setting according to social and economic criteria. The regrounding strategy was not represented in a single cluster, but by activities from all clusters, as the relocation of inputs and farm income involves activities throughout the agri-food system such as composting, self-sufficiency, and pluri-activity.

Potential impacts of the neo-rural phenomenon on social-ecological systems

Neo-rurality and repeasantization entail interaction between subjects and rural host environments (Méndez Sastoque 2012; Trimano 2019a), including a set of transformations in interactions among physical, environmental, social, and symbolic spaces (Table 2). Although no study described in the publications reviewed involved the analysis of these impacts as a main theme, they were mentioned in more than half (n = 100) of the publications. Sociocultural impacts were mentioned most frequently (22.3%), with the creation of new relational links in terms of social innovation [e.g., building of trusting producer–consumer relationships (Orria and Luise 2017; Laforge et al. 2018; Xie 2021), increased associationism and cooperativism (e.g. Dopazo Gallego and De Marco Giachino 2014; Méndez Sastoque 2012)] being the largest subcategory. The second most frequently mentioned impacts were philosophical (20.5%), such as the promotion of new human–nature relationships based on new forms (e.g., ecological, agroecological, permaculture, biodynamic) of agri-food production (e.g., Gretter et al. 2019; Woodhouse 2010). Ecological impacts such as the regulation of nature´s contribution to people (Palacio 2021) were mentioned in 14.8% of publications, followed by demographic impacts (7.5%) such as population fixing and rural rejuvenation.

Agri-food system activities and their impacts on social-ecological systems

Most agri-food system activities and impacts mentioned in the reviewed publications were included in the co-occurrence analysis (Fig. 6). This analysis showed that cooperation and the promotion of mutually supportive stakeholder relationships was supported by diversification activities at the production level. The promotion of new human–nature relationships based on new forms of agri-food production was encouraged through governance components, including the creation of and participation in associations and cooperatives and municipal agroecological distribution activities such as direct sales. The emergence of new relations through the growth of associationism and cooperativism was fostered by horticulture, extensive livestock farming, the diversification of activities and production, and local sales.

Discussion

In the context of multidimensional crisis, phenomena such as neo-rurality and agroecology have emerged as attempts to find alternatives to rural abandonment and a highly unsustainable production model. Given the increasing interest in rural repopulation and new agri-food models in certain social movements, academia, and the policy arena, neo-rurality, and particularly repeasantization, is more frequently emerging as an option to reverse rural and agricultural abandonment. This review is part of a growing body of literature on neo-rurality and repeasantization. It synthetizes previous knowledge and provides insights for future research and critical reflection on definitions, activities encompassed, claimed impacts, and relationships among these factors, particularly in mountainous, remote, and poorly populated regions.

Gaps and biases in neo-rural and new peasantry studies

Our results on temporal trends in neo-rural studies coincide with the increase in current (in recent decades) socio-political debates and governmental agreements on the sustainable repopulation of rural areas. The pro–rural migration trend is growing, particularly in the West, as an alternative to the multisystemic crisis we face (Orozco 2011).

Most case studies reviewed were performed in Europe, followed by Latin America. This distribution is consistent with the origin of the terms “neo-rural” and “new peasant” in the French school of geography and the inclusion of the new peasantry in the framework of the new peasants movements in South America. In addition, Spain is one of the European countries in which neo-rurality has been most studied and discussed in recent decades, corresponding to an increase in rural migration in the country. The results reveal significant gaps in the study of neo-rurality in North America, Asia, and Africa, where only 8% of the included case studies were performed. The first gap could be explained by a methodological limitation of this study, as the term “new farmer,” used in the North American literature as a synonym for “new peasantry,” was not included in the initial set of keywords because it is not specifically related to urban–rural migration and thus did not comply with the inclusion criteria. Although we included studies of new farmers through the application of the snowball methodology, such studies may have been underrepresented in this review. The lack of studies conducted in Asia and Africa could be explained by historical, social, and economic factors, as the neo-rural phenomenon is situated in the context of rural revitalization as a critical response to development and modernization (Pereiro and Prado 2013) and the search for a post-industrial world (Chevalier 1981). However, ecovillages and repeasantization concepts have appeared in Africa (LVC 2011), and Chinese academics are is increasingly interested in new peasants’ innovations for the future of rural development (Xie 2021). Furthermore, the geographical distribution of the included studies may have been affected by the geographical and linguistic biases of the databases searched and the distribution of global academic production, which is concentrated in northern countries.

New agri-food models and back-to-the-land movements are characterized by the greater presence of women relative to the conventional agricultural model and masculinization of rural areas (Monllor 2012; Dopazo Gallego and De Marco Giachino 2014; Laforge et al. 2018; Baylina 2019). However, less than one-quarter of the publications reviewed mention this characteristic, and only about 10% of studies incorporated gender-based analyses. The implementation of innovative agrosocial practices, sexual division of labor, and barriers that women face were the most frequently mentioned topics. We believe that gender-focused work in neo-rural studies is essential and needs to continue, but researchers must be careful about how they situate women in their studies (Urretabizkaia 2020; Iniesta-Arandia et al. 2014).

The social-ecological perspective in neo-rural studies

From diverse approaches, the most common definition of the neo-rural phenomenon is the displacement of people from urban to rural areas in search of life projects. This general description has allowed the application of the neo-rural label to many different groups, such as foreign retirees, floating populations, and remote workers who do not establish relationships with the countryside (Guimond and Simard 2010; Cáceres-Feria and Ballesteros 2017). While these groups share the quest for the rural idyll (Yarwood 2015), the nature of the life projects they seek has lost its original focus (Chevalier 1981; Mercier and Simona 1983). In this sense, the term “neo-rural” may be useless as an analytical category. Some researchers have attempted to delimit the concept based on settlement distances from cities (Schwake 2021), which are related to the type of neo-rurality and its degree of incorporation into the agri-food (especially productive) sector. However, we believe that this delimitation is based on highly variables characteristics that depend on local and socio-demographic contexts. It highlights two issues that may explain the difficulty of conceptualizing the phenomenon. First, the flexible nature of neo-rurality gives rise to identity changes, i.e., one can equally become and stop being neo-rural (Castaño et al. 2020). Second, diverse terms have emerged from academic epistemological exercises, and the people they describe usually do not recognize or relate to them. The latter is linked to local linguistic diversity; for example, farmers in Catalonia refer to themselves as pagesia (“peasant”) (Monllor 2011), whereas small-scale agroecological farmers in most of Spain would not self-identify using the corresponding term campesino. Neo-rurality has a rebellious component related to the forging of new human–nature relationships based on shared values and practices.

We detected another form of bias relating to the separate analysis of neo-rural topics (motivations, barriers, relationships with locals) without the establishment of relationships among. This could be due to the lack of the required interdisciplinary lens and the understanding of the phenomenon only as the migration of its protagonists. Trimano (2019a) proposed the characterization of the neo-rural phenomenon as “the union in the interstice” to solve this theoretical problem:

We call neo-rurality the result of the confluence of trajectories and experiences of heterogeneous actors, who interact in a habitat, at the same time as they are challenged […] (2019, 137).

Thus, the neo-rural is a hybrid entity in terms of those who arrive and those who stay, and the urban and the rural. It aligns with the postmodern perspective in which “rural” has multiple meanings beyond the classic stereotype of the countryside as an agrarian, backward, and depopulated place (Halfacree 1997; Camarero and Oliva 2016). As Pereriro and Prado (2013) argue, rural and urban are not static categories, but discursive imaginaries according to specific sociocultural contexts. We propose that neo-rurality be considered as the interaction between neo-rural people and rural host environments, i.e., as a complex of social-ecological relationships in line with an integrated view of natural systems (Berkes and Folke 1998).

The role of the new peasants in agroecological transition

Except for some key papers (Ploeg 2012; Monllor 2013; Dopazo Gallego and De Marco Giachino 2014; Dourian 2021), the reviewed publications including the term “agroecology” did not describe specific agricultural activities. Moreover, many researchers examining agroecological activities established relationships to organic agriculture or permaculture, but not to the agroecological paradigm. The scientific-technical development of these fields as alternatives to industrial agriculture without the integration of the social component could explain this result (Palomo Campesino 2021).

According to our findings, neo-rural people are currently applying diverse agroecological practices and strategies covering multiple agri-food dimensions (production, transformation, and distribution) and aligned with the values of the new agrosocial paradigm and repeasantization strategies. On-farm transformation, pro-environment practices, and distribution diversification (i.e., local direct sales, labeling, use of multiple sales channels) are related to deepening strategies because they enhance and communicate the added value of products (Dourian 2021). Practices that foster social engagement, cooperation among stakeholders, and the creation of new networks are part of the broadening strategy. In other words, farm-related activities are expanded beyond the productive arena, diversifying income sources, promoting project autonomy from global markets and external inputs, and overall creating farm multifunctionality (Van der Ploeg and Roep 2003). However, equity and gender dimensions are underrepresented in neo-rural research. Social inclusion activities, such as the integration of immigrants into agri-food projects and promotion of their access to land, are the only equity-specific practices that have been examined. Similarly, no agroecological activity has been described as minimizing the gender gap or promoting women’s inclusion in decision making. These gaps need to be addressed to avoid the construction of an agroecological model that fosters inequality (Anderson et al. 2021). As some researchers have claimed, agroecological transition cannot take place without a feminist/gender-focused perspective (Morales 2021; Zaremba et al. 2021).

This review shows that neo-rural people, and specifically new peasants, are key actors in the grounding of agroecological theory and concept of food sovereignty in rural territories (e.g., Rosset and Torres 2016; Laforge et al. 2018). Along with those of young, small-scale, and women farmers, populations of new farmers need to be strengthened to increase the resilience of rural communities (Recanati et al. 2019; Aguilera et al. 2020).

Back-to-the-landers as a driver of change

The addressing of neo-rurality from a social-ecological perspective requires the examination of the biophysical impacts of neo-rural activities on landscapes. Land abandonment driven by urban migration has negative impacts on rural ecosystems, including inhabitants’ quality of life, biodiversity, and ecosystem services (Rey Benayas et al. 2007; Santos-Martín et al. 2019; Quintas-Soriano et al. 2022). Rural repopulation could also have consequences for the social and biophysical dimensions of host ecosystems. However, the reviewed publications mentioned few biophysical impacts, particularly in relation to ecosystem regulation, possibly due to the abundance of social-science publications focusing on social-economic impacts. Of the most commonly cited impacts, three were related to increased relational connections, in social networks and and human-nature connectedness. Neo-rural people and new peasants seem to be enhancing connectivity among agri-food system components, generating new social relations in rural territories and with cities, and promoting new sustainable relations through their activities. The activities and innovations of the new peasantry are contributing to the sustainable transformation of agro-ecoystems, ultimately driving agroecological transition.

Although this review shows the potential of the neo-rural phenomenon and new peasantry in contributing to agroecological transition, it also points to several avenues for future research. We recommend the performance of case studies focused on relationships between agroecological practices and transformation, with the examination of social-ecological impacts. Additionally, the exploration of geographic differences in cultural and socio-demographic factors associated with the neo-rural phenomenon would enable the exploration of neo-rurality as a transnational but context-specific phenomenon.

References

Abrams, J.B., H. Gosnell, N.J. Gill, and P.J. Klepeis. 2012. Re-creating the rural, reconstructing nature: An international literature review of the environmental implications of amenity migration. Conservation and Society 10 (3): 270–284.

AEI-AGRI. 2016. A. E. para la innovación en materia de productividad y sostenibilidad agrícola. EIP-AGRI Focus Group. New entrants into farming. 1–3.

Agroecology Europe. 2021. Integrating agroecology into European agricultural policies. Position paper and recommendations to the European Commission on Eco-schemes. Agroecology Europe: Graux Estate, Belgium.

Aguilar, M. 2003a. Neorrurales en la Sierra Norte de Guadalajara: Huéspedes y anfitriones. Actualidad Leader: Revista De Desarrollo Rural 20: 9–11.

Aguilar, M. 2003b. Neorrurales en Mezquín y Matarraña (Teruel): Volver a empezar. Actualidad Leader: Revista De Desarrollo Rural 20: 13–15.

Aguilera, E., C. Diaz-Gaona, R. Garcia-Laureano, C. Reyes-Palomo, G.I. Guzmán, L. Ortolani, … and V. Rodriguez-Estevez. 2020. Agroecology for adaptation to climate change and resource depletion in the Mediterranean region. A review. Agricultural Systems 181: 102809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102809.

Altieri, M.A., and C.I. Nicholls. 2012. Agroecology scaling up for food sovereignty and resiliency. Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 11: 1–29.

Álvarez, O.F. 2013. Entre la evasión y la nostalgia. Estrategias de la neorruralidad desde la economía social. Gazeta de Antropologia 29(2).

Anderson, C.R., J. Bruil, M.J. Chappell, C. Kiss, and M.P. Pimbert. 2019. From transition to domains of transformation: Getting to sustainable and just food systems through agroecology. Sustainability 11 (19): 5272. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195272.

Anderson, C.R., J. Bruil, M.J. Chappell, C. Kiss, and M.P. Pimbert. 2021. Agroecology now!: Transformations towards more just and sustainable food systems. Cham: Springer Nature.

Aswani, S., A. Lemahieu, and W.H. Sauer. 2018. Tendencias globales del conocimiento ecológico local e implicaciones futuras. PLoS ONE 13 (4): e0195440. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195440.

Barbeta, P. 2020. La transición agroecológica en el actual proceso de recampesinización en la provincia de Chaco (Argentina). Trabajo y Sociedad 35: 447–460.

Baudin, T., and R. Stelter. 2022. The rural exodus and the rise of Europe. Journal of Economic Growth 27 (3): 365–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-022-09206-4.

Baylina, F.M. 2019. La mujer como eje vertebrador de la nueva ruralidad. Un estado de la cuestión. Perspectives on Rural Development 2019 (3): 153–176. https://doi.org/10.1285/i25113775n3p153.

Baylina, M., M. Villarino, M.D.G. Ramon, M.J. Mosteiro, A.M. Porto, and I. Salamaña. 2019. Género e innovación en los nuevos procesos de re-ruralización en España. Finisterra 54 (110): 75–91. https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis16053.

Belasco, W.J. 2007. Appetite for change: How the counterculture took on the food industry. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Bender, O., and S. Kanitscheider. 2012. New immigration into the European alps: Emerging research issues. Mountain Research and Development 32 (2): 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-12-00030.1.

Bennett, J.M. 2017. Changing the agriculture and environment conversation. Nature Ecology & Evolution 1 (1): 0018.

Berkes, F., and C. Folke. 1998. Linking social and ecological systems: Management practices and social mechanisms for building resilience. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Berkes, F., C. Folke, and J. Colding, eds. 2000. Linking social and ecological systems: Management practices and social mechanisms for building resilience. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bertuglia, A., S. Sayadi, C.P. López, and A. Guarino. 2013. El asentamiento de los neorrurales extranjeros en La Alpujarra Granadina: Un análisis desde su perspectiva. Ager 15: 39–73. https://doi.org/10.4422/ager.2012.04.

Bonanno, A., ed. 1994. From Columbus to ConAgra: The globalization of agriculture and food. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Borlaug, N.E. 1971. The green revolution: For bread and peace. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 27 (6): 6–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.1971.11455372.

Bowler, I.R. 1992. The geography of agriculture in developed market economies. Harlow: Longman Scientific & Technical.

Brunet, I., and A. Alarcón. 2008. Turismo rural en Cataluña. Estrategias Empresariales. Revista Internacional de Sociología 66 (49): 141–165.

Cáceres-Feria, R., and E.R. Ballesteros. 2017. Forasteros residentes y turismo de base local. Reflexiones desde Alájar (Andalucía, España). Gazeta de Antropologia 33 (1).

Calvário, R. 2017. Food sovereignty and new peasantries: On re-peasantization and counter-hegemonic contestations in the Basque territory. Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (2): 402–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2016.1259219.

Calvário, R., and I. Otero. 2015. Neorrurales. Ecología Política 49: 71–75.

Camarero, L. 1993. Del éxodo rural y del éxodo urbano. Madrid: Ministerio de Agricultura. Pesca y alimentación.

Camarero, L. 2017. Trabajadores del campo y familias de la tierra. Instantáneas de la desagrarización. AGER. Revista de Estudios de Despoblación. https://doi.org/10.4422/ager.2017.01.

Camarero, L., and J. Oliva. 2016. Understanding rural change: Mobilities, diversities, and hybridizations. Sociální Studia/social Studies 13 (2): 93–112. https://doi.org/10.5817/soc2016-2-93.

Campbell, B.M., D.J. Beare, E.M. Bennett, J.M. Hall-Spencer, J.S.I. Ingram, F. Jaramillo, R. Ortiz, N. Ramankutty, J.A. Sayer, and D. Shindell. 2017. Agriculture production as a major driver of the Earth system exceeding planetary boundaries. Ecology and Society 22 (4): 8. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09595-220408.

Capitalismo y campesinado son dos lógicas contrapuestas de entender la vida y de relacionarnos con la naturaleza. 2018. Baladre.

Cardoso, M.M. 2019. An approach to multi-territoriality in the rururban areas. Horticulturists in Santa Fe, Argentina, as a case study. Bitacora Urbano Territorial 29 (2): 81–88. https://doi.org/10.15446/bitacora.v29n2.65532.

Carlisle, L. 2014. Critical agrarianism. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 29 (2): 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170512000427.

Carneiro, M.J. 1998. Ruralidade: Novas identidades em construção. Estudos Sociedade e Agricultura 11: 53–75.

Castaño, P. E., J. Luis Molina, and M.J. Lubbers. 2020. “La vuelta al campo” en Cataluña: Una perspectiva antropológica. [Doctoral dissertation, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona]. Institutional repository - Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Cazella, A.A. 2001. Les installations agricoles nouvelles : Le cas des agriculteurs néo-ruraux dans l’Aude (France). Espace, Populations, Sociétés 19 (1): 101–108. https://doi.org/10.3406/espos.2001.1979.

CCOO y Federación Agroalimentaria Castilla y León. 2014. El fenómeno de la NeoRuralidad y sus posibilidades ante las políticas de Desarrollo Rural en Castilla y León 2015-2020. Grupo de Trabajo Del Sector Agroalimentario de Castilla y León., 1–72.

Chevalier, M. 1981. Les phénomènes néo-ruraux. Espace Géographique 10 (1): 33–47. https://doi.org/10.3406/spgeo.1981.3603.

Chiodo, E., A. Fantini, L. Dickes, T. Arogundade, R.D. Lamie, L. Assing, C. Stewart, and R. Salvatore. 2019. Agritourism in mountainous regions-insights from an international perspective. Sustainability 11 (13): 3715. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133715.

Cid Aguayo, B.E. 2014. Movimientos agroecológico y neo campesino: Respuestas postmodernas a la clásica cuestión agraria. Agroalimentaria 20 (39): 65–78.

Corrado, A. 2010. New peasantries and alternative agro-food networks: the case of réseau semences paysannes. In From community to consumption: New and classical themes in rural sociological research. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Cortes-Vazquez, J.A. 2014. A natural life: Neo-rurals and the power of everyday practices in protected areas. Journal of Political Ecology 21 (1): 493–515. https://doi.org/10.2458/v21i1.21148.

Dal Bello, U.B., C. Marques, O. Sacramento, and A. Galvão. 2022a. Neo-rural small entrepreneurs’ motivations and challenges in Portugal’s low density regions. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 16 (6): 900–923. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-04-2021-0047.

Dal Bello, U., C.S. Marques, O. Sacramento, and A.R. Galvão. 2022b. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and local economy sustainability: Institutional actors’ views on neo-rural entrepreneurship in low-density Portuguese territories. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 33 (1): 44–63. https://doi.org/10.1108/meq-04-2021-0088.

De Bustillo, P.M. 2017. Neorrurales: Contra la corriente de la despoblación rural. El Ecologista 93: 28–31.

De Master, K. 2013. Navegando la descampesinización y la recampesinización. Limitaciones potenciales de un enfoque universal de Soberanía Alimentaria para los pequeños agricultores polacos. Documento para la conferencia Food Sovereignty: A Critical Dialog Conference Papers, Universidad de Yale/ISS.

De Matheus e Silva, L. 2013. Sembrando nuevos agricultores: Contraculturas espaciales y recampesinización. Polis (Santiago) 12 (34): 57–71. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-65682013000100004.

Domínguez, D. 2012. Recampesinizacción en la argentina del siglo XXI. Psicoperspectivas 11 (1): 134–157.

Dopazo Gallego, P., and De Marco Giachino, D. 2014. La reVuelta al Campo. Sistematización de experiencias de jóvenes en la incorporación al campo. https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/estudis/2014/174202/revcamsis_a2014.pdf.

Dourian, T. 2021. New farmers in the south of Italy: Capturing the complexity of contemporary strategies and networks. Journal of Rural Studies 84 (March): 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.03.003.

Doyon, M., J.L. Klein, L. Veillette, C. Bryant, and C. Yorn. 2013. La néoruralité au Québec: Facteur présentiel d’enrichissement collectif ou source d’embourgeoisement? Geographie Economie Societe 15 (1): 117–137. https://doi.org/10.3166/ges.15.117-137.

Entrena-Durán, F. 2012. La ruralidad en España: De la mitificación conservadora al neorruralismo. Cuadernos De Desarrollo Rural 9 (69): 39–65.

Erdogan, G., and S. Şahin. 2019. A model for neo rural ecological design approach, Mugla-Turkiye. Kent Akademisi 12 (2): 257–269.

FAO. 2017. The future of food and agriculture: Trends and challenges. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

FAO. 2019. TAPE Tool for Agroecology Performance Evaluation 2019 – Process of development and guidelines for application. Test version. Rome.

Fernandes, J., et al. 2016. Pueblos de montaña: Problemas, perspectivas y propuestas, vistos desde las montañas de Aboboreira, Marão y Montemuro, en el noroeste de Portugal. Revista de Geografía y Ordenación del Territorio 9: 113–137. https://doi.org/10.17127/got/2016.9.006.

Flament-Ortun, S., B. Macias Garcia, and N. Monllor i Rico. 2017. Nuevos perfiles en la incorporación de personas jóvenes al campo: tendencias emergentes desde una perspectiva de soberanía alimentaria. Elikadura21: coloquio internacional.

Forssell, S., and L. Lankoski. 2015. The sustainability promise of alternative food networks: An examination through “alternative” characteristics. Agriculture and Human Values 32: 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-014-9516-4.

Gallar Hernández, D., and R. Acosta Naranjo. 2014. La resignificación campesinista de la ruralidad: La Universidad Rural Paulo Freire. Revista de Dialectologia y Tradiciones Populares 69 (2): 285–304. https://doi.org/10.3989/rdtp.2014.02.002.

Garcia, F. 1977. Pouvoirs en souffrance. Néo-ruraux et collectivités rurales du Pays de Sault oriental. Études Rurales 65 (1): 101–108. https://doi.org/10.3406/rural.1977.2192.

García Vega, M.Á. 2015. Savia nueva en el campo. El País. https://elpais.com/economia/2015/02/06/actualidad/1423217987_812557.html.

García-Fernández, J. 2020. Acercar campo y ciudad. Algunas reflexiones compartidas. Cuadernos Entretantos 7.

Giordano, A., V. Luise, and A. Arvidsson. 2018. The coming community. The politics of alternative food networks in Southern Italy. Journal of Marketing Management 34 (7–8): 620–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2018.1480519.

Giuliani, G. 1990. Neo-ruralismo: O novo estilo dos velhos modelos. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais 5 (14): 59–68.

Gliessman, S. 2018. Defining agroecology. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 42 (6): 599–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2018.1432329.

Gómez-Ullate, M. 2004. Contracultura y asentamientos alternativos en la España de los 90: un estudio de Antropología Social. [Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Complutense de Madrid]. Institutional repository – Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

González, F. 2015. La ‘nueva ruralidad’ en Cañuelas. Entre la agroecología y las nuevas urbanizaciones. Mundo Agrario 16 (31).

Gretter, A., C. D. Torre, F. Maino, and A. Omizzolo. 2019. New farming as an example of social innovation responding to challenges of Inner Mountain Areas of Italian Alps. Revue de Géographie Alpine 107–2: 0–16. https://doi.org/10.4000/rga.6106.

Guillemin, P., and M. Bermond. 2021. Agricultrices néorurales à l’épreuve de la séparation conjugale. Travail, Genre et Societes 45 (1): 97–114. https://doi.org/10.3917/tgs.045.0097.

Guimond, L., and M. Simard. 2010. Gentrification and neo-rural populations in the Québec countryside: Representations of various actors. Journal of Rural Studies 26 (4): 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2010.06.002.

Hajdu, A., and N. Mamonova. 2020. Prospects of agrarian populism and food sovereignty movement in post-socialist Romania. Sociologia Ruralis 60 (4): 880–904. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12301.

Hakimi-Pradels, N. 2021. La fabrique des hauts-lieux des alternatives sociales et écologiques dans les marges rurales françaises : Le cas de la montagne limousine. Belgeo Revue belge de géographie 2: 0–16. https://doi.org/10.4000/belgeo.48884.

Halfacree, K. 1997. Postmodern perspectives on counterurbanisation. Contested countryside cultures: Otherness, marginalisation and rurality. London: Routledge.

Halfacree, K. 2007. Back-to-the-land in the twenty-first century – making connections with rurality. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 98 (1): 3–8.

Halfacree, K., and M.J. Rivera. 2012. Moving to the countryside and staying: Lives beyond representations. Sociologia Rurais 52 (1): 92–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2011.00556.x.

Heinz, M. 2015. Neues leben in alten dörfern? Eine rekonstruktive analyse der aneignung ländlicher räume. SWS - Rundschau 55 (3): 258–278. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10734-240210.

HLPE. 2019. Agroecological and other innovative approaches for sustainable agriculture and food systems that enhance food security and nutrition. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. Rome.

Ingram, J. 2011. A food systems approach to researching food security and its interactions with global environmental change. Food Security 3: 417–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-011-0149-9.

Iniesta-Arandia, I., C. Piñeiro, C. Montes, and B. Martín-López. 2014. Women and the conservation of agroecosystems: An experiential analysis in the Río Nacimiento region of Almería (Spain)/Mujeres y conservación de agroecosistemas Análisis de experiencias en la comarca almeriense del río Nacimiento. Psyecology 5 (2–3): 214–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/21711976.2014.942516.

Jacob, J. 1997. New pioneers: The back-to-the-land movement and the search for a sustainable future. University Park: Penn State Press.

Janin, B. 1986. Le Val d’ Aoste: Vers le néo-ruralisme. Revue De Géographie Alpine 74 (1): 203–210.

Karpinski, B. 2020. Neorrurais agroecologistas e o desenvolvimento rural sustentável: o caso das produtoras e dos produtores agroecológicos da rama. [Master´s Thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul]. Institutional repository - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul.

Karpinski, B., T. Bieger, A. Matte and M. Conterat. 2020. La recampesinización como manifestación agroecológica: Campesinos y neorrurales construyendo autonomía. Cuadernos de Agroecologia 15 (2).

Koensler, A. 2020. Prefigurative politics in pratice: concrete utopias in Italy´s food sovereignty activism. Mobilization: An International Quarterly 25 (1): 133–150. https://doi.org/10.17813/1086-671-25-1-101.

La asociación Artiborain. N.d. Garguera Viva.

La llamada. 2018. Boletin de Agitaciòn Rural.

La Vía Campesina (LVC). 2010. La agricultura campesina sostenible puede alimentar al mundo. LVC Views, 1–15.

La Via Campesina (LVC). 2011. Primer Encuentro de Formadores@s en Agroecología en la Región 1 de África de la Vía Campesina, 12-20 de Junio de 2011, Declaración de Shashe.

Laforge, J., A. Fenton, V. Lavalée-Picard, and S. McLachlan. 2018. New farmers and food policies in Canada. Canadian Food Studies/La Revue Canadienne Des Études Sur l’alimentation 5 (3): 128–152. https://doi.org/10.15353/cfs-rcea.v5i3.288.

Lecy, J. D., and K. E. Beatty. (2012). Representative literature reviews using constrained snowball sampling and citation network analysis.

Liu, J., T. Dietz, S.R. Carpenter, M. Alberti, C. Folke, E. Moran, A.N Pell ... and W.W. Taylor. 2007. Complexity of coupled human and natural systems. Science 317: 1513–1516. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1144004.

Llobera, F. 2014. Agroecologia y neorruralidad: Metodologias de acompañamiento y formación. XI Congreso de SEAE: Agricultura Ecológica Familiar, Vitoria, España.

Lojka, B., N. Teutscherová, A. Chládová, L. Kala, P. Szabó, A. Martiník, … and G. Lawson. 2021. Agroforestry in the Czech Republic: What hampers the comeback of a once traditional land use system?. Agronomy 12(1): 69.

Losardo, M. 2016. New ways of living, as old as the world: Best practices and sustainability in the example of the italian ecovillage network. Studia Ethnologica Croatica 28 (1): 47–70. https://doi.org/10.17234/SEC.28.3.

Madero Navajas, F. 2020. Movimientos sociales y derecho a la tierra: agroecología y soberanía alimentaria como alternativas. Quaderns D´animació i Educació Social 32 (6).

Mailfert, K. 2007. New farmers and networks: How beginning farmers build social connections in France. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 98 (1): 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2007.00373.x.

Márquez-Barrenechea, A., M. García-Llorente, X. López-Medellín, F. Llobera, and M. Redondo. 2020. How do policy-influential stakeholders from the Madrid region (Spain) understand and perceive the relevance of agroecology and the challenges for its regional implementation? Landbauforsch/journal of Sustainable and Organic Agricultural Systems 70 (2): 145–156.

Martín, L. 2020. Larga vida a las pastoras. El País. https://elpais.com/sociedad/pienso-luego-actuo/2020-12-04/larga-vida-a-las-pastoras.html.

Martinez-Torres, M.E., and P.M. Rosset. 2010. La Vía Campesina: The birth and evolution of a transnational social movement. The Journal of Peasant Studies 37 (1): 149–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150903498804.

Matson, P.A., W.J. Parton, A.G. Power, and M.J. Swift. 1997. Agricultural intensification and ecosystem properties. Science 277 (5325): 504–509. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.277.5325.504.

Méndez Sastoque, J. 2012. El neorruralismo como práctica configurante de dinámicas sociales alternativas: Un estudio de caso. Revista Luna Azul 34: 113–130.

Mercier, C., and G. Simona. 1983. Le néo-ruralisme: Nouvelles approches pour un phénomène nouveau. Revue de Géographie Alpine 71 (3): 253–265. https://doi.org/10.3406/rga.1983.2535.

Miguel Alonso, J. 2019. El movimiento neorrural frente al despoblamiento rural de la provincia de Burgos: promoción de la producción y consumo local, la sostenibilidad y la simplicidad voluntaria. [Doctoral dissertation, Universidade Nova de Lisboa]. Institutional repository - Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

Milone, P., and F. Ventura. 2019. New generation farmers: Rediscovering the peasantry. Journal of Rural Studies 65: 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.12.009.

Milone, P., F. Ventura, and J. Ye, eds. 2015a. Constructing a new framework for rural development. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Milone, P., F. Ventura, and J. Ye. 2015b. Constructing a new framework for rural development. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Ministerio de Agricultura, P. y A. 2021. Estudio sobre el acceso a la tierra. Documento final del grupo focal de acceso a la tierra. Gobierno de España.

Monllor, N. 2012. El nuevo campesinado emergente. Revista Soberanía Alimentaria, Biodiversidad y Cultura 11: 13–16.

Monllor, N. 2013. El nuevo paradigma agrosocial, futuro del nuevo campesinado emergente. Polis 12 (34): 203–223. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-65682013000100011.

Monllor y Rico, N. 2011. Explorando al joven campesinado: caminos, prácticas y actitudes en el marco de un nuevo paradigma agrosocial. Estudio comparativo entre el suroeste de la provincia de Ontario y las comarcas gerundenses. [Doctoral dissertation, Universitat de Girona]. Institutional repository - Universitat de Girona.

Monllor i Rico, N., and A.M. Fuller. 2016. Newcomers to farming: Towards a new rurality in Europe. Documents d’Analisi Geografica 62 (3): 531–551. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/dag.376.

Mora, V.L. 2018. Líneas de fuga “neorrurales” de la literatura española contemporánea. Tropelías: Revista de Teoría de La Literatura y Literatura Comparada 4 (4): 198–221. https://doi.org/10.26754/ojs_tropelias/tropelias.201843071.

Morales, E. 2016. Los nuevos pobladores en el medio rural de Castilla y León. [Doctoral Dissertation, Universidad de Valladolid]. Institutional repository Universidad de Valladolid.

Morales, H. 2021. Agroecological feminism. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 45 (7): 955–956. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2021.1927544.

Morillo, M. J. and J.C. De Pablos. 2012. Neorrurales, la construcción de un estilo de vida. VI Congreso Andaluz de Sociología, Cádiz.

Moss, L., ed. 2006. The amenity migrants: seeking and sustaining mountains and their cultures. Wallingford: Cabi.

Muzlera, J. 2019. Neorruralidad en el sudeste bonaerense. Uso Del Espacio y Sociabilidades. Contemporânea 9 (2): 563–588. https://doi.org/10.4322/2316-1329.104.

Nates, B., and S. Raymond. 2007. Buscando la naturaleza. Migración y dinámicas rurales contemporáneas. Madrid: Anthropos.

Nigh, R., and A.A. González Cabañas. 2015. Reflexive consumer markets as opportunities for new peasant farmers in Mexico and France: Constructing food sovereignty through alternative food networks. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 39 (3): 317–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2014.973545.

Niska, M., H.T. Vesala, and K.M. Vesala. 2012. Peasantry and entrepreneurship as frames for farming: Reflections on farmers’ values and agricultural policy discourses. Sociologia Ruralis 52 (4): 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2012.00572.x.

Nogué i Font, J. 1988. El fenómeno neorrural. Agricultura y Sociedad 47: 145–175.

Nogué i Font, J. 2016. El reencuentro con el lugar: Nuevas ruralidades, nuevos paisajes y cambio de paradigma. Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica 62 (3): 489. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/dag.373.

Núñez, T. 2012. El problema del campo no es la falta de jóvenes. Soberanía Alimentaria, Biodiversidad y Culturas 11: 6–10.

Oliva, J. 2010. Rural melting-pots, mobilities and fragilities: Reflections on the Spanish case. Sociologia Ruralis 50 (3): 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2010.00516.x.

Oliva, J., and M.J. Rivera. 2020. Crisis and post-crisis in rural territories. Crisis and Post-Crisis in Rural Territories. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50581-3.

Oliveira, H., and G. Penha-Lopes. 2020. Permaculture in Portugal: Social-ecological inventory of a re-ruralizing grassroots movement. European Countryside 12 (1): 30–52. https://doi.org/10.2478/euco-2020-0002.

Oliveri, F. 2015. A network of resistances against a multiple crisis: SOS Rosarno and the experimentation of socio-economic alternative models. Partecipazione e Conflitto 8 (2): 504–529. https://doi.org/10.1285/i20356609v8i2p504.

Ollivier, G., D. Magda, A. Mazé, G. Plumecocq, and C. Lamine. 2018. Agroecological transitions: What can sustainability transition frameworks teach us? An ontological and empirical analysis. Ecology and Society 23 (2): 5. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09952-230205.

Orozco, A.P. 2011. Crisis multidimensional y sostenibilidad de la vida. Investigaciones Feministas 2: 35.

Orria, B., and V. Luise. 2017. Innovation in rural development: “Neo-rural” farmers branding local quality of food and territory. Italian Journal of Planning Practice 7 (1): 125–153.

Ostrom, E. 2009. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 325: 419–422.

Öztürk, M., J. Jongerden, and A. Hilton. 2017. The (re)production of the new peasantry in Turkey. Journal of Rural Studies 61: 244–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.10.009.

Page, M. J., J.E. McKenzie, P.M. Bossuyt, I. Boutron, T.C. Hoffmann, C.D. Mulrow, … and D. Moher. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery 88: 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906.

Palacio, S. 2021. De la despoblación a la repoblación rural de las montañas. Ecosistemas 30 (1): 2164. https://doi.org/10.7818/ecos.2164.

Palomo Campesino, S. (2021). Analizando los agroecosistemas como sistemas socioecológicos: una mirada integradora desde la agroecología. . [Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid]. Institutional repository - Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

Pereiro, X., and S. Prado. 2013. Cross-cultural perceptions and discourses between rural and urban in Galicia. In Shaping rural areas in Europe. Perceptions and outcomes on the present and the future. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6796-6.

Picciani, A.L. 2016. Discusiones teóricas sobre la dinámica funcional en el vínculo espacial urbano y rural. Pampa 14: 9–28. https://doi.org/10.14409/pampa.v0i14.6110.

Pinto-Correia, T., M. Almeida, and C. Gonzalez. 2016. A local landscape in transition between production and consumption goals: Can new management arrangements preserve the local landscape character? Geografisk Tidsskrift - Danish Journal of Geography 116 (1): 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167223.2015.1108210.

Plews-Ogan, E., M.J. Mariola, and A. Ananta. 2017. Polyculture, autonomy, and community: The pursuit of sustainability in a northern Thai farming village. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 15 (4): 418–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2017.1335044.

Quintas-Soriano, C., A. Buerkert, and T. Plieninger. 2022. Effects of land abandonment on nature contributions to people and good quality of life components in the Mediterranean region: A review. Land Use Policy 116: 106053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106053.

Quirós, J. 2019. Nacidos, criados, llegados: Relaciones de clase y geometrías socioespaciales en la migración neorrural de la Argentina contemporánea. Cuadernos de Geografía: Revista Colombiana de Geografía 28 (2): 271–287. https://doi.org/10.15446/rcdg.v28n2.73512.

Ratier, H. 2002. Rural, Ruralidad, Nueva Ruralidady Contraurbanizacion. Un Estado De Cuestion. Revista de Ciencias Humanas 31: 09–29. https://periodicos.ufsc.br/index.php/revistacfh/article/view/25175/22145.

Recanati, F., C. Maughan, M. Pedrotti, K. Dembska, and M. Antonelli. 2019. Assessing the role of CAP for more sustainable and healthier food systems in Europe: A literature review. Science of the Total Environment 653: 908–919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.377.

Renau, L.D.R. 2018. Ecoaldeas en España: ¿En busca de una transformación social emancipatoria? Cogent Social Sciences 4 (1): 1468200. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1468200.

Retière, M., and P.E.M. Marques. 2019. A justiça ecológica em processos de reconfiguração do rural: Estudo de casos de neorrurais no estado de São Paulo. Revista De Economia e Sociologia Rural 57 (3): 490–503. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9479.2019.184109.

Rey Benayas, J.M., A. Martins, J.M. Nicolau, and J.J. Schulz. 2007. Abandonment of agricultural land: an overview of drivers and consequences. CABI Reviews 2. https://doi.org/10.1079/PAVSNNR20072057.

Rivera, M.J. 2020. Arraigo de nuevos residentes y revitalización rural: Posibilidades y limitaciones de una relación simbiótica. Panorama Social 31: 75–85.

Rivera, M.J. and Mormont, M. 2006. Neo-rurality and the different meanings of the countryside. Les mondes ruraux à l’épreuve des sciences sociales. Dijon: Quae/Symposcience.

Rodríguez Eguizabal, A., and E. Trabada Crende. 1991. De la ciudad al campo: El fenómeno social neorruralista en España. Política y Sociedad 9 (9): 73–86.

Roseman, S.R., S.P. Conde, and X.P. Pérez. 2013. Antropología y nuevas ruralidades. Gazeta de Antropologia 29(2). https://doi.org/10.30827/digibug.28509.

Rosset, P. 2011. Food sovereignty and alternative paradigms to confront land grabbing and the food and climate crises. Development 54 (1): 21–30.

Rosset, P.M., and M.E.M. Torres. 2016. Agroecología, territorio, recampesinización y movimientos sociales. Estudios Sociales. Revista de Alimentación Contemporánea y Desarrollo Regional 25 (47): 273–299.

Rubio, J.A.P., and M.S. Sánchez. 2012. Motivaciones y orientaciones de los nuevos pobladores en áreas rurales alejadas. Revista Española de Sociología 17 (2012): 49–71.

Ruiz-Escudero, F. 2019. La red de ecoaldeas: Repoblación, autogobierno, autogestión y autosuficiencia alimentaria. PH: Boletín del Instituto Andaluz del Patrimonio Histórico 27 (98): 24–28. https://doi.org/10.33349/2019.98.4469.

Ruiz de Lobera, F. 2018. Crónica de un reportero profano. Postmetropolis Editorial.

Ruiz Escudero, F. 2012. Alternativas y resistencias desde lo rural-urbano: aproximación al estudio de las experiencias comunitarias agroecológicas. [Doctoral dissertation, Universidad de Córdoba]. Institutional repository – Universidad de Córdoba.

Sabourin, E., J.-P. Tonneau, and M.A. De Menezes. 2004. Is there a new peasant agriculture project ? An analysis based on brazilian and french examples. Acta Agriculturae Serbica 9 (17): 19–32.