Abstract

Background and objective

Population-based estimates of the socioeconomic burden of multiple sclerosis (MS) are limited, especially regarding primary healthcare. This study aimed to estimate the excess costs of people with MS that could be attributed to their MS, including primary healthcare.

Methods

An observational study was conducted of the 2806 working-aged people with MS in Stockholm, Sweden and 28,060 propensity score matched references without MS. Register-based resource use was quantified for 2018. Annual healthcare costs (primary, specialised outpatient, and inpatient healthcare visits along with prescribed drugs) and productivity losses (operationalised by sickness absence and disability pension days) were quantified using bottom-up costing. The costs of people with MS were compared with those of the references using independent t-tests with bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to isolate the excess costs of MS from the mean difference.

Results

The mean annual excess costs of MS for healthcare were €7381 (95% CI 6991–7816) per person with MS with disease-modifying therapies as the largest component (€4262, 95% CI 4026–4497). There was a mean annual excess cost for primary healthcare of €695 (95% CI 585–832) per person with MS, comprising 9.4% of the excess healthcare costs of MS. The mean annual excess costs of MS for productivity losses were €13,173 (95% CI 12,325–14,019) per person with MS, predominately from disability pension (79.3%).

Conclusions

The socioeconomic burden of MS in Sweden from healthcare consumption and productivity losses was quantified, updating knowledge on the cost structure of the substantial excess costs of MS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common non-traumatic neurological disease among young adults [1]. Besides necessitating healthcare, MS may affect one’s work capacity. Accordingly, MS can pose an economic burden on patients, healthcare and social security budgets as well as a loss of production to society [2]. The all-age prevalence of MS in Sweden is relatively high at 189 per 100,000 [3, 4]. Therefore, accurate estimates of the socioeconomic burden of MS are essential to define the magnitude of the disease in monetary terms, justify interventions, and support decision makers in formulating policies and prioritising resources [2, 5].

The mean excess societal costs of MS in Sweden in 2012 from healthcare consumption and productivity losses were estimated in comparison with references to be 23,507 Euros (EUR) more per person with MS (2020 values) [6]. However, population-based cost estimates from Sweden, whether the all-cause costs among people with MS (PwMS) or the costs attributable to MS, have not yet included costs from primary healthcare use as such data is not available at a national level [6,7,8,9]. This has led to underestimations. Furthermore, studies on the primary healthcare utilisation among PwMS in Sweden have to date been of small groups, before the introduction of more efficacious disease-modifying therapies, and without reference groups [10,11,12,13,14]. Nonetheless, they suggest that PwMS have widespread primary healthcare use with a range of healthcare professionals [11]. PwMS are recommended to have a multidisciplinary care team [15]. Accordingly, primary healthcare has an important role in managing PwMS’ symptoms alongside neurology care [16]. Cost estimates need updating to reflect earlier diagnoses, increasing treatment options, and improved clinical course [17,18,19]. The excess costs of MS can be more accurately estimated with register data allowing for comparison with a reference group to isolate the additional cost per person due to MS and the underlying resource use may indicate unmet needs [20, 21].

We aimed to estimate the annual excess costs of MS, comparing the healthcare costs, including primary healthcare, and productivity losses among working-aged PwMS with those among population-based matched references.

Methods and materials

Study design and data sources

A one-year register-based cost-of-illness study was conducted. The resource utilisation, healthcare costs, and productivity losses of residents of Stockholm County, Sweden, with MS were compared with those of a population-based matched reference group without MS.

Individual-level data was linked from seven registers, using pseudonymised personal identity numbers, to build the study population and inform resource utilisation (Online Resource 1).

Study population

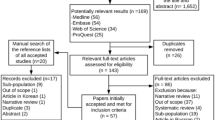

All individuals 19–64 years of age alive and living in Stockholm County on both 31 December 2017 (n = 1,392,834) were identified from the Longitudinal Integration Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies (LISA) and cross-checked for being alive and resident in Stockholm County in 2018 in LISA and the Cause of Death Register (n = 1,354,161) (Fig. 1).

Flow chart of inclusion into the study population. Prior diagnosis of MS (ICD-10: G35 or ICD-8/9: 340) and other demyelinating diseases (ICD-10: G36, G37, H46, or ICD-9: 340, 377, 367, 323, 341) were identified in the NPR, VAL, or MiDAS [23,24,25]. MS disease-modifying therapies were identified in the SPDR (ATC codes: L01DB07, L01XC02, L01XC10, L03AB07, L03AB08, L03AB13, L03AX13, L04AA23, L04AA27, L04AA31, L04AA34, L04AA36, L04AA40, L04AC01, L04AX07, and N07XX09) [23, 25, 26]. ATC Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System, ICD International Classification of Diseases, MiDAS Micro Data for the Analysis of Social Insurance register, MS multiple sclerosis, NPR National Patient Register, PwMS People with multiple sclerosis, SMSreg Swedish Multiple Sclerosis Registry, SPDR Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, VAL Region Stockholm’s healthcare database.

The PwMS were identified from the Stockholm residents who were also in the Swedish MS Registry (SMSreg) (n = 3400), with an MS diagnosis recorded 31 December 2017 or prior (n = 2862). Of the 179 in the SMSreg but with a missing MS diagnosis date, 132 with onset dates before the end of 2017 were included. Lastly, individuals with MS onset when < 18 years were excluded as their clinical course may differ from adult-onset MS (n = 188 excluded) [22]. In total, 2806 PwMS were included.

A population-based matched reference group was identified from the Stockholm residents, who have never been diagnosed with MS (not included in the SMSreg, n = 1,350,761; Fig. 1). Individuals were then excluded from being potential references if having diagnosis codes (main or secondary) for MS or other demyelinating diseases [23,24,25] in the National Patient Register (NPR), Region Stockholm’s healthcare database (VAL), or the Micro Data for the Analysis of Social Insurance register (MiDAS), or MS disease-modifying therapies [23, 25, 26] dispensed according to the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register (SPDR) up until 31 December 2018 (n = 2066 excluded). From this pool of potential references (n = 1,348,695), propensity-score matching selected ten reference individuals for each individual with MS (n = 28,060) [27,28,29,30].

Resource use and costs

A prevalence-based costing approach was used to estimate the costs incurred within the year attributable to MS from a societal perspective [31, 32]. Total costs of all-cause resource use for each cost category were estimated through a bottom-up approach by multiplying each individual’s total quantity of resource use in 2018 with the corresponding unit costs summarised in Table 1 [32]. A reference year of 2020 was used whenever possible for the unit costs [32, 33]. Costs are presented in EUR (1 EUR = 10.4848 Swedish krona (SEK)) [34].

Healthcare costs

Healthcare costs included the costs of healthcare visits (inpatient, specialised outpatient, and primary healthcare) and drugs (prescribed drugs dispensed in pharmacies and MS disease-modifying therapies administered within healthcare).

The costs for both inpatient (with a discharge date in 2018) and specialised outpatient visits, respectively, were derived from the diagnosis-related group (DRG) code for the visit in the NPR along with the patient copayment [35, 36]. Nationwide retrospective DRG weights were used to translate the DRG code into a cost [37, 38]. If the DRG was not in the retrospective weight list for 2018 (n = 355 inpatient and n = 19,248 specialised outpatient visits), the prospective nationwide DRG weight for 2018 from the National Board of Health and Welfare was used instead [39].

Primary healthcare contacts were sourced from the VAL and classified according to the type of contact and healthcare professional. The contacts were then costed relative to the average cost for a clinic visit with a physician (Online Resource 2) and the relevant patient copayment [35, 40,41,42]. Primary healthcare was further analysed. The type of healthcare visit was presented as clinic (116,032 visits including 2691 missed appointments), home, and distance contact. Type of healthcare professional referred to the first registered professional, with 91.9% of contacts with 1 professional. Two categorisations were used:

-

1.

Physicians, nurses, or other healthcare professionals; and

-

2.

Physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nurse assistants, or other healthcare professionals.

Drug costs comprised the costs for prescribed drugs dispensed in community pharmacies and other MS disease-modifying therapies administered within healthcare. Drug costs related to the quantity of the specific substance dispensed, with the patient copayment [43] and the portion of the costs publicly financed all obtained directly from the SPDR. In addition, further MS disease-modifying therapies administered within healthcare and not available in the SPDR were included. Start and end dates of treatment from the SMSreg were used to estimate the months on treatment. Average unit costs per month were applied based on recommended dosing. Drug costs were also presented as MS disease-modifying therapy costs (sourced from either the SPDR or SMSreg) and drug costs excluding disease-modifying therapies.

Productivity losses

The costs of productivity losses were estimated from the net days of sickness absence and disability pension from MiDAS, representing days with lost production to society due to morbidity [31]. The human capital approach was used to estimate productivity losses, as per the Swedish guidelines for economic evaluations [31, 44]. Productivity losses were derived by multiplying the net months of sickness absence and disability pension (months with lost production), respectively, by the sum of the national average monthly gross salary and the employers’ social security contribution [45, 46]. Full employment of the study population was assumed.

Total societal costs

Annual total societal costs per person were the sum of healthcare costs and productivity losses.

Statistical analyses

Propensity score matching was used in this observational study to mimic randomisation by constructing a reference group with a similar covariate distribution to the PwMS to reduce bias in the estimation of the costs of MS [27,28,29]. This matching strategy was deemed advantageous as it provided intuitive estimates of the cost of MS by design rather than conditioned on a subgroup of PwMS in subsequent analyses, and it allowed for simpler statistical analyses with reduced variance in the estimates [27, 29]. Furthermore, it can be problematic to directly adjust for comorbidities in register-based MS research due to difficulty in disentangling whether another diagnosis is unrelated or connected as a symptom or consequence of MS [21, 60]. Adjustment for diagnoses related to MS would be an overadjustment and lead to underestimations of the excess costs of MS.

The propensity score was estimated with a logistic regression model with MS status (MS vs. no MS) as the outcome and the following baseline factors, with information from 31 December 2017, as independent variables: sex (women, men), age (years), born in Sweden (yes, no), degree of urbanisation of their municipality of residence (binary variables for each, cities: densely populated areas; towns and suburbs: intermediate density areas; and rural areas: thinly populated areas), educational level dichotomised as university education (yes, no), and family composition classified as child living at home (yes, no) and cohabiting or married (yes, no). The predicted probabilities of MS status (propensity scores) were then used to create a matched sample of references. We used a calliper width of 0.25 and the greedy nearest neighbour matching method without replacement [27,28,29]. To determine covariate balance between the PwMS and matched references, we calculated standardised mean differences for each included baseline factor before matching among all potential references (n = 1,348,695) in comparison with the PwMS and then reassessed the standardised mean differences for the 28,060 selected references. The threshold to indicate imbalance was set at > 0.1 [61, 62]. Common support was assessed by comparing the propensity score distributions of the PwMS and references.

After the propensity score matching, descriptive statistics of the matched study population were conducted. All individuals were included in the statistical analyses to enable inference on the entire study population, including those with zero costs. Costs were reported as annual means per person with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The estimated population mean is widely thought as the cost statistic of most interest to policy makers and easily interpretable [63]. Median values and interquartile ranges (IQR) are also reported given the characteristic right-skewed cost data with a mass of zero observations [63]. Among all, 16.6% of individuals accrued 0 healthcare costs (PwMS = 2.1%, references = 18.0%) and 81.6% had 0 productivity losses (PwMS = 51.1%, references = 84.6%) within 2018. The relative difference in mean per person costs was calculated as a ratio by dividing the costs among PwMS with those among references. The proportions of individuals with resource use underlying each cost category were presented (yes, no). Differences in resource use between the PwMS and the matched references were tested with chi-square tests.

Excess costs were the costs of MS, isolated by comparing the all-cause costs among PwMS with those of the matched references [21]. Accordingly, excess costs were the mean cost differences between the PwMS and the references for each cost category that we calculated with direct comparisons from two-tailed Student’s t-tests. These excess cost estimates without adjustment provide a mean value across all individuals, irrespective of age, sex, or other characteristics [64]. The relatively large study population and study design with matched references enabled relatively simple analyses [63]. Furthermore, further adjustment with regression modelling was not considered necessary to remove residual confounding after the propensity score matching, as none of the observed covariates indicated imbalance (standardised mean differences > 0.1), suggesting a well matched reference group [62]. Lastly, bootstrapped bias-corrected percentile CIs for the excess cost estimates were computed from 2000 iterations to indicate the plausible range of values for the population parameter [65].

Data management (except for costing in STATA v15) and statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4. The Regional Ethical Review Board of Stockholm, Sweden approved the project.

Results

Study population

The mean age of the PwMS was 45.3 years (95% CI 44.9–45.7). Through propensity score matching, 28,060 residents in Stockholm without MS were matched to the 2806 PwMS. All baseline factors included in the propensity score had standardised mean differences < 0.1 after matching (Table 2) and the distributions of the propensity scores overlapped (Online Resource 3).

Costs of PwMS

The mean annual costs for healthcare resource consumption and productivity losses of PwMS and matched references are visualised in Online Resource 4 and detailed in Online Resource 5. Productivity losses were the largest cost for both the PwMS (16,922 EUR per person, 95% CI 16,101–17,742) and references (3748 EUR, 95% CI 3608–3888), with an average 4.5-fold higher productivity loss among PwMS. The corresponding mean annual healthcare costs were 9595 EUR (95% CI 9189–10,000) per person with MS and 2214 EUR (95% CI 2146–2282) for the references, equating to 4.3-fold higher healthcare costs among PwMS.

Excess costs of MS and differences in resource utilisation

The excess costs of MS with bootstrapped 95% CIs are visualised in Fig. 2 and summarised in Table 3. There was a mean annual excess productivity loss of MS of 13,173 EUR (95% CI 12,352–14,019) per person with MS. Disability pension costs comprised 79.3% of this excess. More PwMS had productivity losses (48.9%) than references (15.3%; p value < 0.001) (Online Resource 6).

Annual mean excess costs of MS per person for healthcare consumption and productivity losses, as well as the sum of all-cause costs among PwMS and their propensity score matched references without MS. Notes: Total societal costs are in orange, healthcare costs and component costs are displayed in blue, and the productivity losses and component costs are displayed in green. The paler of the respective colour represents the excess costs of MS. The costs stated refer to these excess costs of MS. Each entire column represents the sum of all-cause costs among PwMS and the darker portion of the column the costs among the matched references without MS. The annual exchange rate for 2020 from SEK to EUR from Eurostat was 10.4848 [34]. Prior to currency conversion, if required, the unit costs were inflated to 2020 Swedish prices using the annual Harmonised Indices of Consumer Prices for healthcare available from Eurostat [59]. EUR Euros, MS multiple sclerosis, PwMS People with multiple sclerosis, SEK Swedish krona.

Differences in the proportions of users of healthcare resources and excess costs of MS for healthcare were observed. Among PwMS, specialised outpatient healthcare settings had the most users (79.6% PwMS vs. 48.9% references, p value < 0.001). References had most users in primary healthcare settings but at a lower proportion than among the PwMS (65.5% references vs. 75.9% PwMS, p value < 0.001). A mean annual excess cost of MS for healthcare of 7381 EUR (95% CI 6991–7816) was discerned per person with MS. While PwMS had a higher percentage of their total annual healthcare costs publicly funded (96.8% vs. 90.4%), there was a mean annual excess cost for visit fees and drugs paid out-of-pocket of 91 EUR (95% CI 73–107) per person with MS. There was a mean annual excess drug cost of 4479 EUR per person with MS (95% CI 4224–4769). Disease-modifying therapies contributed 95.2% of these excess costs.

Primary healthcare utilisation and costs

The excess primary healthcare costs of MS are presented by healthcare professional in Fig. 3 and tabulated in Online Resource 7. Primary healthcare costs were 2.4-times higher per person with MS, with a mean annual cost for primary healthcare of PwMS of 1181 EUR (95% CI 1060–1302) per person and 486 EUR (95% CI 475–498) for the references. This resulted in a mean annual excess cost of 695 EUR (95% CI 585–832) per person with MS. Primary healthcare constituted 9.4% of the excess healthcare costs of MS. A higher proportion of PwMS had primary healthcare visits at the clinic (74.3% vs. 65.3%, p value < 0.001) or home (13.8% vs. 1.2%, p value < 0.001) compared with references, but similar proportions had distance contacts (3.78% vs. 3.74%, p value 0.917). Excess costs of MS for clinic visits (237 EUR, 95% CI 197–274), home visits (444 EUR, 95% CI 342–560) were observed but no excess costs of MS for distance contacts (p value 0.830). Physicians were the most contacted healthcare professional among PwMS (66.5%) and references (58.5%, p value < 0.001). Higher proportions of PwMS than references had contact with nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and nurse assistants (p values < 0.001). Excess costs of MS were observed for all investigated healthcare professionals. Having MS was associated with a mean annual excess cost per person of 86 EUR (95% CI 66–107) for primary healthcare contacts with physicians, 198 EUR (95% CI 146–251) with nurses, and 397 EUR (95% CI 325–493) with other healthcare professionals.

Annual mean excess costs of MS per person for primary healthcare by healthcare professional. Notes: The paler colour represents the excess costs of MS. The costs stated refer to these excess costs of MS. Each entire column represents the sum of all-cause costs among PwMS and the darker portion those among the matched references without MS. The first registered healthcare professional per contact is used. Primary healthcare costs in this figure are presented excluding the patient out-of-pocket copayment in the form of visit fees. The mean annual cost per person for copayments for primary healthcare were estimated to be 52 EUR (95% CI 51–54) for PwMS and 38 EUR 95% CI 38–39) for the references. The annual exchange rate for 2020 from SEK to EUR from Eurostat was 10.4848 [34]. Prior to currency conversion, the unit costs were inflated to 2020 Swedish prices using the annual Harmonised Indices of Consumer Prices for healthcare available from Eurostat [59]. CI confidence interval, EUR Euros, MS multiple sclerosis, PwMS People with multiple sclerosis, SEK Swedish krona.

Discussion

This population-based register study quantifies the socioeconomic burden of MS in Sweden as the excess costs of MS calculated in comparison with the costs of propensity-score matched references. The mean annual excess costs were 7381 EUR for healthcare and 13,173 EUR for production losses per working-aged person with MS. In relative terms, this equated to 4.3-fold higher healthcare costs and 4.5-fold higher productivity losses per person with MS. PwMS had a mean annual excess cost of 695 EUR per person for primary healthcare, mostly from contacts with healthcare professionals other than physicians. The excess costs of MS outside the health system were substantial, especially due to lost productivity when disability pensioned.

Our findings update previous estimates from Sweden. Gyllensten et al. found that the mean excess costs of MS for working-aged PwMS were lower in 2012 at 8807 EUR for healthcare costs and 14,700 EUR for productivity losses, than in 2006 (2020 values) [6]. Our estimates are slightly lower again, notwithstanding inclusion of primary healthcare. The excess costs of MS were driven by disease-modifying therapies and permanent reductions of work capacity (disability pension costs), consistent with previous research [6, 66]. In addition to earlier diagnoses [19], new treatments have entered the market [17] changing healthcare utilisation, e.g., moving from inpatient to outpatient healthcare, as well as reducing MS disability. Accordingly, offsets of these treatment costs from savings of other healthcare resources [67] and maintained work capacity [6] have been suggested. Economic modelling also supports the notion that early initiation of treatment is cost saving to society [68]. This finding was robust across models, including a Sweden-specific model, and more costs were saved from averting MS the longer the time horizon [68]. Our relatively low excess healthcare costs of MS could also be influenced by rituximab being widely used off-label [17]. We observed 43.3% with rituximab infusions within 2018. The high use of rituximab, especially among PwMS with high inflammatory activity or relapses [47], influences our cost estimates given the lower unit costs compared with alternative treatments available.

Our study is unique in quantifying the excess costs of MS for primary healthcare from real-world resource consumption. These costs comprised 9% of the excess healthcare costs of MS, updating knowledge on the cost structure of MS. We observed widespread primary healthcare utilisation by PwMS and excess primary healthcare costs of MS were largely for professionals other than physicians, consistent with the recommendations for multidisciplinary care to manage MS and the wide range of symptoms [15]. Therefore, indicating not just more but a different pattern of utilisation by PwMS. In a previous study of 121 PwMS in Stockholm County, nurses, physicians, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists were the most sought after primary healthcare professionals over 10 years of follow-up [14]. With a single observation year, the same professionals each represented > 5% of all primary healthcare contacts among the PwMS, with the addition of nurse assistants. In any country, healthcare for PwMS is provided by both primary care and specialised units, in particular neurology departments or even MS-specific centres. In Sweden, there are roughly 60 neurology centres providing specialised MS healthcare. This study shows that in Stockholm, primary care for PwMS includes rehabilitative services by occupational therapists and physiotherapists and care provided by nurses with smaller additional costs for primary healthcare physicians. Hence suggesting that neurologists provide not only specialised MS care but also service more general medical needs of PwMS. It is possible that this pattern of healthcare use is more prominent in Stockholm, owing to the high concentration and proximity to neurologists, compared with smaller towns and rural areas.

Excess costs of MS were observed for all healthcare settings. The excess costs of MS for primary healthcare were of a smaller magnitude than for the higher cost settings of specialised out- and inpatient healthcare. PwMS often have parallel use of healthcare services in different departments and types of healthcare [11]. Future research should investigate the department, procedures, and diagnoses contributing to the excess healthcare costs of MS and underlying changes in productivity in the era of modern therapy [14].

The socioeconomic burden of MS reaches beyond the healthcare system [66]. Productivity losses increasingly outweigh the healthcare costs with worsening MS, as MS particularly affects young adults with the potential for many more years of paid work [7, 66]. Our excess productivity losses of MS were larger than previous estimates from newly-diagnosed PwMS and predominately from permanent work incapacity [9]. Whereas the mean annual excess sickness absence costs around MS diagnosis were larger than observed in our prevalent cohort [9]. The excess productivity losses owing to sickness absence and disability pension reflect challenges that PwMS face to maintain work capacity and remain in or return to work. These excess costs of MS can indicate unmet needs among this population regarding morbidity as well as work adaptions. Interventions, including early initiation of high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies, to promote the maintenance of work capacity of PwMS are required to address this unmet need and high costs.

The major strengths of this study were the population-based design and the use of high-quality register microdata [69,70,71,72]. The excess costs of MS mirrored real-world resource utilisation and were not dependent on recall. We had a relatively large study population compared with previous Swedish studies of primary healthcare use among PwMS [11, 12, 73]. Further, a reference group from the same source population was included to calculate the excess costs of MS. Excess costs are well suited for isolating the costs of MS [21]. Comorbidities are common among PwMS and may also influence wider resource use, with complexity as to the causal relationship with MS [60, 74]. It is not always apparent which diagnosis the resources should be attributed to [21, 60]. Hence estimates of excess costs through comparisons with a reference group have a lower risk of classification errors owing to whether the wider register-based resource use was due to MS, or not, than costs informed only by resource use coded with an MS diagnosis [6]. Accordingly, we were able to estimate the excess costs directly and indirectly related to MS, to accurately measure the wider costs of MS. Propensity-score methods are increasingly used in MS and cost-of-illness studies with observational real-world data to reduce confounding and account for individual-level factors in expected resource use [21, 28, 61, 75]. By achieving covariate balance after matching, we avoided the need for double adjustment through modelling [62]. However, there is potential for residual confounding from other factors, whether unmeasured or unknown [29].

Our findings should be interpreted considering limitations. The PwMS were sourced from the SMSreg, which has high coverage [76]. However, 841 individuals were removed as potential references for having an MS code in another register. These individuals may have differed to those in the SMSreg, e.g., individuals with MS codes for primary healthcare or disability pension may have been older, have progressive MS, and not be treated with disease-modifying therapies. Rituximab was an exclusion for potential references because of the high frequency of use for MS but possibly excluded individuals not having MS [17, 48]. Optic neuritis (H46), one of the other demyelinating diseases, was unable to be identified from the NPR.

The main limitation is the lack of register data for both PwMS and references regarding other relevant cost categories, including community services, adaptations, informal care, reduced productivity at work, as well as productivity losses from sickness absence spells ≤ 14 days. The true excess costs of MS are likely to be higher with these costs included.

For the included costs, there are also important considerations. Healthcare costs were largely based on aggregate average unit costs as proxies for the actual costs [38]. These should cover the standard treatment burden and foster comparison with other studies, but may underestimate costs in situations requiring higher than average resources. To avoid temporal biases from the rearrangements of healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic, earlier unit costs were used for healthcare visits and inflated to 2020 values. If the routines implemented continue, these costs are accordingly underestimated. The administration costs for disease-modifying therapies are presumed to be included within the specialised outpatient healthcare costs, although visits without involvement of a physician were not recorded in the data and consequently the full treatment costs are underestimated. There is also a slight overestimation of patient copayments from including separate caps for specialised outpatient and primary healthcare visits. Lastly, only primary healthcare financed by Region Stockholm was captured in the data, leading to underestimations of care sought elsewhere.

The generalisability of the excess cost estimates and resource use may be limited to settings with similar universal coverage for social security and healthcare and labour market/job security regulations. The observed patterns of resource utilisation and resulting costs reflect the healthcare organisation, medical traditions, and access of the working-aged individuals with adult-onset MS in a largely urban area. Sweden has a comparatively low average number of hospital beds per capita as well as physician consultations [77], the latter suggested to be related to the central role of nurses [78]. The regional financing and provision of healthcare in Sweden may also influence the service availability and utilisation patterns [79]. There are also likely differences in the magnitude of costs and distribution of cost components among the PwMS, for example, by disability level [7, 66] or among those with late onset MS [80, 81]. The latter being much less studied. The excess costs of MS presented are the additional cost on top of regular expenditure per individual. The excess costs of MS are considerable with approximately 20,000 working aged PwMS throughout Sweden [82].

Conclusions

In this population-based study with real-world data, costs for healthcare consumption and lost production were compared between a prevalent cohort of working-aged people with MS and propensity-score matched references to estimate the magnitude of the socioeconomic burden of MS. PwMS had substantially higher costs from healthcare use, including primary healthcare, and production losses than references. Primary healthcare contributed a tenth of the excess healthcare costs of MS, largely from contacts with professionals other than physicians, updating knowledge on the cost structure of MS. The excess costs of MS from lost production in this prevalent MS cohort were larger in magnitude than healthcare consumption. The substantial excess costs of MS indicate potential unmet needs in the MS population. Interventions to reduce morbidity and support PwMS to stay or return to work are vital.

Availability of data and materials

The sensitive microdata used in this study is administered by the Division of Insurance Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, and cannot be shared publicly in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation, the Swedish Data Protection Act, the Swedish Ethical Review Act, and the Swedish Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act. This type of sensitive data can only be made available to researchers after a legal review if meeting the criteria to access this type of sensitive and confidential data. Readers may contact Professor Kristina Alexanderson (kristina.alexanderson@ki.se) for further information regarding the data.

Code availability

Data management and statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4, except for data management for the cost outcomes in STATA v15.

Abbreviations

- ATC:

-

Anatomical therapeutic chemical classification system

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DRG:

-

Diagnosis-related group

- EUR:

-

Euros

- ICD:

-

International classification of diseases

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- LISA:

-

Longitudinal integration database for health insurance and labour market studies

- MiDAS:

-

Micro data for the analysis of social insurance

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- NPR:

-

National patient register

- PwMS:

-

People with multiple sclerosis

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SEK:

-

Swedish krona

- SMSreg:

-

Swedish multiple sclerosis registry

- SPDR:

-

Swedish prescribed drug register

- VAL:

-

Region Stockholm’s healthcare database

References

Giovannoni, G., Butzkueven, H., Dhib-Jalbut, S., et al.: Brain health: time matters in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 9(Suppl 1), S5–S48 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2016.07.003

Jo, C.: Cost-of-illness studies: concepts, scopes, and methods. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 20(4), 327–337 (2014). https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2014.20.4.327

Ahlgren, C., Oden, A., Lycke, J.: High nationwide prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Sweden. Mult. Scler. 17(8), 901–908 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458511403794

Walton, C., King, R., Rechtman, L., et al.: Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult. Scler. 26(14), 1816–1821 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458520970841

Rice, D.P.: Cost of illness studies: what is good about them? Inj. Prev. 6(3), 177–179 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1136/ip.6.3.177

Gyllensten, H., Wiberg, M., Alexanderson, K., Friberg, E., Hillert, J., Tinghog, P.: Comparing costs of illness of multiple sclerosis in three different years: a population-based study. Mult. Scler. 24(4), 520–528 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517702549

Gyllensten, H., Kavaliunas, A., Alexanderson, K., Hillert, J., Tinghog, P., Friberg, E.: Costs and quality of life by disability among people with multiple sclerosis: a register-based study in Sweden. Mult. Scler. J. Exp. Transl. Clin. 4(3), 2055217318783352 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/2055217318783352

Karampampa, K., Gyllensten, H., Yang, F., et al.: Healthcare, sickness absence, and disability pension cost trajectories in the first 5 years after diagnosis with multiple sclerosis: a prospective register-based cohort study in Sweden. Pharmacoecon. Open 4(1), 91–103 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-019-0150-3

Murley, C., Tinghog, P., Alexanderson, K., Hillert, J., Friberg, E., Karampampa, K.: Cost-of-illness progression before and after diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: a nationwide register-based cohort study in Sweden of people newly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and a population-based matched reference group. Pharmacoeconomics 39(7), 835–851 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-021-01035-4

Johansson, S., Ytterberg, C., Gottberg, K., Widen Holmqvist, L., von Koch, L.: Use of health services in people with multiple sclerosis with and without fatigue. Mult. Scler. 15(1), 88–95 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458508095730

Gottberg, K., Einarsson, U., Ytterberg, C., Fredrikson, S., von Koch, L., Holmqvist, L.W.: Use of health care services and satisfaction with care in people with multiple sclerosis in Stockholm County: a population-based study. Mult. Scler. 14(7), 962–971 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458508089688

Ytterberg, C., Lundqvist, S., Johansson, S.: Use of health services in people with multiple sclerosis with and without depressive symptoms: a 2-year prospective study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 13, 365 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-365

Ytterberg, C., Johansson, S., Gottberg, K., Holmqvist, L.W., von Koch, L.: Perceived needs and satisfaction with care in people with multiple sclerosis: a 2-year prospective study. BMC Neurol. 8(1), 36 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-8-36

Chruzander, C., Johansson, S., Gottberg, K., et al.: A 10-year population-based study of people with multiple sclerosis in Stockholm, Sweden: use of and satisfaction with care and the value of different factors in predicting use of care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 15, 480 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1144-1

National Board of Health and Welfare [Socialstyrelsen]. National guidelines care for multiple sclerosis and parkinson's disease: support for steering and management [In Swedish: Nationella riktlinjer Vård vid multipel skleros och Parkinsons sjukdom: Stöd för styrning och ledning] Falun, Sweden 2016. Report No.: 2016:12:1

Papathanasiou, A., Saunders, L., Sare, G.: Symptom management of patients with multiple sclerosis in primary care: focus on overlooked symptoms. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 71(704), 139–141 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp21X715193

Eriksson, I., Komen, J., Piehl, F., Malmstrom, R.E., Wettermark, B., von Euler, M.: The changing multiple sclerosis treatment landscape: impact of new drugs and treatment recommendations. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 74(5), 663–670 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-018-2429-1

Kalincik, T., Diouf, I., Sharmin, S., et al.: Effect of disease-modifying therapy on disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis over 15 years. Neurology 96(5), e783–e797 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000011242

Thompson, A.J., Banwell, B.L., Barkhof, F., et al.: Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 17(2), 162–173 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2

Asche, C.V., Singer, M.E., Jhaveri, M., Chung, H., Miller, A.: All-cause health care utilization and costs associated with newly diagnosed multiple sclerosis in the United States. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 16(9), 703–712 (2010). https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.9.703

Onukwugha, E., McRae, J., Kravetz, A., Varga, S., Khairnar, R., Mullins, C.D.: Cost-of-illness studies: an updated review of current methods. Pharmacoeconomics 34(1), 43–58 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0325-4

McKay, K.A., Hillert, J., Manouchehrinia, A.: Long-term disability progression of pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis. Neurology 92(24), e2764–e2773 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000007647

Marrie, R.A., Yu, N., Wei, Y., Elliott, L., Blanchard, J.: High rates of physician services utilization at least 5 years before multiple sclerosis diagnosis. Mult. Scler. 19(8), 1113–1119 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458512471877

McKay, K.A., Friberg, E., Razaz, N., Alexanderson, K., Hillert, J.: Long-term socioeconomic outcomes associated with pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 78(4), 478–482 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.5520

Wijnands, J.M.A., Kingwell, E., Zhu, F., et al.: Health-care use before a first demyelinating event suggestive of a multiple sclerosis prodrome: a matched cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 16(6), 445–451 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30076-5

Eriksson, I., Cars, T., Piehl, F., Malmstrom, R.E., Wettermark, B., von Euler, M.: Persistence with dimethyl fumarate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a population-based cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 74(2), 219–226 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-017-2366-4

Rosenbaum, P.R., Rubin, D.B.: The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70(1), 41–55 (1983). https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/70.1.41

Karim, M.E., Pellegrini, F., Platt, R.W., Simoneau, G., Rouette, J., de Moor, C.: The use and quality of reporting of propensity score methods in multiple sclerosis literature: a review. Mult. Scler. 28, 1352458520972557 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458520972557

Stuart, E.A.: Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat. Sci. 25(1), 1–21 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1214/09-STS313

Austin, P.C.: An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar. Behav. Res. 46(3), 399–424 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.568786

Tarricone, R.: Cost-of-illness analysis. What room in health economics? Health Policy 77(1), 51 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.07.016

Drummond, M.F., Sculpher, M.J., Torrance, G.W., O’Brien, B.J., Stoddart, G.L.: Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2005)

Ringborg, A., Martinell, M., Stalhammar, J., Yin, D.D., Lindgren, P.: Resource use and costs of type 2 diabetes in Sweden—estimates from population-based register data. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 62(5), 708–716 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01716.x

Eurostat. ECU/EUR exchange rates versus national currencies. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tec00033/default/table?lang=en (2021). Accessed 05/08/2021

Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions [Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner]. Patient fees in outpatient healthcare 2020 [In Swedish: Patientavgifter i öppen hälso-och sjukvård år 2020] (2020). 08-01-2020

Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions [Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner]. Patient fees in inpatient healthcare 2020 [In Swedish: Avgifter i sluten vård år 2020] (2020). 08-01-2020

Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions [Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner]. Cost per patient Somatic: Retrospective DRG-weights CC-grouped in+outpatient 2012–2019 [Kostnad per patient KPP Somatik: Retrospectiva DRG-vikter CC-grupperat SV+ÖV 2012–2019] [In Swedish]. Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions [Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting]. https://skr.se/ekonomijuridikstatistik/statistik/kostnadperpatientkpp/kppsomatik.1077.html (2020). Accessed 05-08-2021

Špacírová, Z., Epstein, D., Espín, J.: Are costs derived from diagnosis-related groups suitable for use in economic evaluations? A comparison across nine European countries in the European Healthcare and Social Cost Database. Eur. J. Health Econ. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-022-01444-y

National Board of Health and Welfare [Socialstyrelsen]. Weight lists for NordDRG [In Swedish: Viktlistor för NordDRG]. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/utveckla-verksamhet/e-halsa/klassificering-och-koder/drg/viktlistor/ (2020). Accessed 10-08-2020

Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions [Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner]. Statistics of healthcare and regional development 2019: Operations and economy in the Regions [In Swedish: Statistik om hälso- och sjukvård samt regional utveckling 2019 Verksamhet och ekonomi i regioner] Stockholm, Statistics section Doeas; 2020 August 2020

Wallstrom, S., Ekman, I., Omerovic, E., Ulin, K., Gyllensten, H.: Cohort study of healthcare use, costs and diagnoses from onset to 6 months after discharge for takotsubo syndrome in Sweden. BMJ Open 9(2), e027814 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027814

Sabale, U., Bodegard, J., Sundstrom, J., et al.: Healthcare utilization and costs following newly diagnosed type-2 diabetes in Sweden: a follow-up of 38,956 patients in a clinical practice setting. Prim. Care Diabetes 9(5), 330–337 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2015.01.001

The Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency [Tandvårds- och läkemedelsförmånsverket (TLV)]. High cost protection [In Swedish: Högkostnadsskyddet]. https://www.tlv.se/lakemedel/hogkostnadsskyddet.html (2021). Accessed 11-02-2022

The Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency [Tandvårds- och läkemedelsförmånsverket (TLV)]. The Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency's general guidelines [In Swedish: Tandvårds- och läkemedelsförmånsverkets allmänna råd]. https://www.tlv.se/download/18.467926b615d084471ac3230c/1510316374332/TLVAR_2017_1.pdf. (2017). Accessed 11-02-2022

Statistics Sweden [Statistiska centralbyrån]. Average monthly salary by sector 1992–2020. https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/labour-market/wages-salaries-and-labour-costs/salary-structures-whole-economy/pong/tables-and-graphs/average-monthly-salary-by-sector/ (2021). Accessed 05-08-2021

Swedish Tax Authority [Skatteverket]. Total and percentages- income year 2020 [Belopp och procent – inkomstår 2020] [In Swedish]. https://www.skatteverket.se/privat/skatter/beloppochprocent/2020.4.7eada0316ed67d728238ec.html. Accessed 24-11-2021

Swedish MS Association [Svenska MS-Sällskapet (SMSS)]. SMSS Information on Rituximab 210118 [In Swedish: SMSS information om Rituximab 210118]. https://www.mssallskapet.se/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/SMSS-info-om-Rituximab-210118.pdf (2021). Accessed 23-07-2021

FASS.se. Mabthera (Rituximab) [In Swedish]. FASS. https://www.fass.se/LIF/product?userType=2&nplId=19980602000029&docType=30&scrollPosition=600s2019 (2021). Accessed 23-07-2021

Salzer, J., Svenningsson, R., Alping, P., et al.: Rituximab in multiple sclerosis: a retrospective observational study on safety and efficacy. Neurology 87(20), 2074–2081 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003331

FASS.se. Tysabri (Natalizumab) [In Swedish]. FASS. https://www.fass.se/LIF/product?nplId=20040916001115&userType=0&docType=6&scrollPosition=751.33331298828122019#dose (2020). Accessed 23-07-2021

The Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency [Tandvårds- och läkemedelsförmånsverket (TLV)]. Lemtrada (alemtuzumab) Health economic assessment [Lemtrada (alemtuzumab) Hälsoekonomiskt kunskapsunderlag]. https://www.tlv.se/download/18.467926b615d084471ac339b6/1510316400569/halsoekonomiskt-kunskapsunderlag-lemtrada.pdf (2014). Accessed 23-07-2021

FASS.se. Lemtrada (Alemtuzumab) [In Swedish]. https://www.fass.se/LIF/product?userType=0&nplId=20121223000012&docType=7&scrollPosition=228 (2021). Accessed 23-07-2021

Swedish MS Association [Svenska MS-Sällskapet (SMSS)]. Alemtuzumab [In Swedish]. https://www.mssallskapet.se/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Alemtuzumab-200207-1.pdf (2020). Accessed 23-07-2021

The Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency [Tandvårds- och läkemedelsförmånsverket (TLV)]. Arzerra included in the high cost protection with limitations 3266/2014[Arzerra ingår i högkostnadsskyddet med begränsning 3266/2014]. 2015. https://www.tlv.se/beslut/beslut-lakemedel/begransad-subvention/arkiv/2015-01-30-arzerra-ingar-i-hogkostnadsskyddet-med-begransning.html (2021). Accessed 05-08-2021

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Arzerra (ofatumumab). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/arzerra (2021). Accessed 05-08-2021

The Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency [Tandvårds- och läkemedelsförmånsverket (TLV)]. Assessment for decision-making by county councils: Ocrevus (Ocrelizumab) [Underlag för beslut i landstingen: Ocrevus (okrelizumab)] Dnr 335/2016 (2016). 03-09-2018

FASS.se. Ocrevus (Ocrelizumab) [In Swedish]. https://www.fass.se/LIF/product?userType=0&nplId=20160427000077 (2021). Accessed 23-07-2021

Swedish MS Association [Svenska MS-Sällskapet (SMSS)]. Ocrelizumab information. https://www.mssallskapet.se/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Ocrelizumab_information.pdf (2017). Accessed 23-07-2021

Eurostat. HICP (2015 = 100) - annual data (average index and rate of change). https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=prc_hicp_aind&lang=en (2021). Accessed 05-08-2021

Magyari, M., Sorensen, P.S.: Comorbidity in multiple sclerosis. Front. Neurol. 11, 851 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00851

Salter, A., Lancia, S., Cutter, G., et al.: A propensity-matched comparison of long-term disability worsening in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with dimethyl fumarate or fingolimod. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 14, 17562864211021176 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/17562864211021177

Nguyen, T.L., Collins, G.S., Spence, J., et al.: Double-adjustment in propensity score matching analysis: choosing a threshold for considering residual imbalance. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 17(1), 78 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0338-0

Mihaylova, B., Briggs, A., O’Hagan, A., Thompson, S.G.: Review of statistical methods for analysing healthcare resources and costs. Health Econ. 20(8), 897–916 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1653

Andersson, E., Persson, S., Hallen, N., et al.: Costs of diabetes complications: hospital-based care and absence from work for 392,200 people with type 2 diabetes and matched control participants in Sweden. Diabetologia 63(12), 2582–2594 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05277-3

DiCiccio, T.J., Efron, B.: Bootstrap confidence intervals. Stat. Sci. 11(3), 189–212 (1996)

Schriefer, D., Haase, R., Ness, N.H., Ziemssen, T.: Cost of illness in multiple sclerosis by disease characteristics—a review of reviews. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 22, 1–19 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2022.1987218

Curkendall, S.M., Wang, C., Johnson, B.H., et al.: Potential health care cost savings associated with early treatment of multiple sclerosis using disease-modifying therapy. Clin. Ther. 33(7), 914–925 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.05.049

Tinelli, M., Pugliatti, M., Antonovici, A., et al.: Averting multiple sclerosis long-term societal and healthcare costs: the Value of Treatment (VoT) project. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 54, 103107 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2021.103107

Ludvigsson, J.F., Almqvist, C., Bonamy, A.K., et al.: Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 31(2), 125–136 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-016-0117-y

Alping, P., Piehl, F., Langer-Gould, A., Frisell, T., Group, C.-M.S.: Validation of the Swedish Multiple Sclerosis Register: further improving a resource for pharmacoepidemiologic evaluations. Epidemiology 30(2), 230–233 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000948

Ludvigsson, J.F., Andersson, E., Ekbom, A., et al.: External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 11, 450 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-450

Ludvigsson, J.F., Svedberg, P., Olen, O., Bruze, G., Neovius, M.: The longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA) and its use in medical research. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 34(4), 423–437 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00511-8

Brundin, L., Kobelt, G., Berg, J., Capsa, D., Eriksson, J., European Multiple Sclerosis, P.: New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: results for Sweden. Mult. Scler. 23(2_suppl), 179–191 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517708682

Smith, K.A., Burkill, S., Hiyoshi, A., et al.: Comorbid disease burden among MS patients 1968–2012: a Swedish register-based cohort study. Mult. Scler. 27(2), 268–280 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458520910497

Ssegonja, R., Alaie, I., Philipson, A., et al.: Depressive disorders in adolescence, recurrence in early adulthood, and healthcare usage in mid-adulthood: a longitudinal cost-of-illness study. J. Affect. Disord. 258, 33–41 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.077

Swedish Neuro Registry [Svenska Neuroregister]. Annual Report 2019 [In Swedish: Årsrapport 2019]. https://www.neuroreg.se/media/ulql2mip/multipel-skleros-%C3%A5rsrapport-2019.pdf (2020). Accessed 27-01-2021

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the European Union: Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: 8: State of Health in the EU Cycle. OECD Publishing, Paris (2018)

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD): Consultations with Doctors. OECD Publishing, Paris (2013)

Johansson, N., Jakobsson, N., Svensson, M.: Regional variation in health care utilization in Sweden—the importance of demand-side factors. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18(1), 403 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3210-y

Martinelli, V., Rodegher, M., Moiola, L., Comi, G.: Late onset multiple sclerosis: clinical characteristics, prognostic factors and differential diagnosis. Neurol. Sci. 25(Suppl 4), S350–S355 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-004-0339-8

Buscarinu, M.C., Reniè, R., Morena, E., et al.: Late-onset MS: disease course and safety-efficacy of DMTS. Front. Neurol. 13, 829331 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.829331

Murley, C., Friberg, E., Hillert, J., Alexanderson, K., Yang, F.: Validation of multiple sclerosis diagnoses in the Swedish National Patient Register. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 34(12), 1161–1169 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00558-7

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institutet. The project was supported by unrestricted research grants from Biogen. We utilised data from the REWHARD consortium, supported by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet grant number: 2017-00624). The design of the study, data collection, analyses, interpretations of data, and manuscript drafting were performed without involvement of the funding bodies. Biogen was given the opportunity to comment on the manuscript before submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors CM, PT, KA, JH, KK, and EF contributed to the study conception and design. Data for this project was obtained by KA and JH. Data management and analysis were performed by CM. Statistical interpretation was conducted by CM, PT, FST, AM, KA, KK, and EF. The first draft of the manuscript was written by CM and all authors commented on versions of the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

CM, AM, FT, and EF were partly funded by an unrestricted research grant from Biogen. KA has received unrestricted researcher-initiated grants from Biogen. EF has received unrestricted researcher-initiated grants from Celgene. PT has previously received salaries partly funded by Biogen and has no conflicts to declare. KK has previously been employed and received salaries from Karolinska Institutet which were partly funded by Biogen, but not for conducting this study and has not received any salary from Karolinska Institutet or Biogen since October 2019. Presently, KK is working full time at Bristol Myers Squibb. JH received honoraria for serving on advisory boards for Biogen and Novartis and speaker’s fees from Biogen, Merck-Serono, Bayer-Schering, Teva, and Sanofi-Aventis. He has served as principal investigator for projects sponsored by, or received unrestricted research support from, Biogen, Merck-Serono, TEVA, Novartis, and Bayer-Schering. JH’s MS research is also funded by the Swedish Research Council.

Ethics approval

The project received ethical approval from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (reference numbers: 2007/762-31; 2009/23-32; 2009/1917-32; 2010/466-32; 2011/806-32; 2011/1710-32; 2014/236-32; and 2016/1553-32). The study was performed in accordance with the tenants of the Declaration of Helsinki and later amendments. Informed consent from the research participants was not applicable due to the use of pseudonymised data from total population administrative registers and that we do not hold the details revealing the identity of the participants. Individuals with MS included in the Swedish MS Registry provided consent to their neurologist to enter their information into the register for both clinical and research purposes.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murley, C., Tinghög, P., Teni, F.S. et al. Excess costs of multiple sclerosis: a register-based study in Sweden. Eur J Health Econ 24, 1357–1371 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-022-01547-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-022-01547-6

Keywords

- Multiple sclerosis

- Cost of illness

- Real world data

- Disability pension

- Sick leave

- Primary healthcare

- Healthcare costs

- Productivity losses

- Medical/health economics

- Propensity score matching