Abstract

Introduction

For pancreatic procedures, transverse and midline or combined approaches are used. Having an increased morbidity after pancreatic surgery, these patients have an increased risk of developing an incisional hernia. In the following, we will analyze how the results of incisional hernia surgery after pancreatic surgery are presented in the Herniamed Registry.

Methods

Hospitals and surgeons from Germany, Austria and Switzerland can voluntarily enter all routinely performed hernia operations prospectively into the Herniamed Registry. All patients sign a special informed consent declaration that they agree to the documentation of their treatment in the Herniamed Registry. Perioperative complications (intraoperative complications, postoperative complications, complication-related reoperations and general complications) are recorded up to 30 days after surgery. After 1, 5, and 10 years, patients and primary care physicians are contacted and asked about any pain at rest, pain on exertion, chronic pain requiring treatment or recurrence. This retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data compares the outcomes of minimally invasive vs open techniques in incisional hernia repair after pancreatic surgery.

Results

Relative to the total number of all incisional hernia patients in the Herniamed Registry, the proportion after pancreatic surgery with 1-year follow-up was 0.64% (n = 461) patients. 95% of previous pancreatic surgeries were open. Minimally invasive incisional hernia repair was performed in 17.1% and open repair in 82.9% of cases. 23.2% of the defects were larger than 10 cm and 32.8% were located laterally or were a combination of lateral and medial defects. Among the few differences between the collectives, a significantly higher rate of defect closure (58.1% vs 25.3%; p < 0.001) and drainage (72.8% vs 13.9%; p < 0.001) was found in the open repairs, and larger meshes were seen in the minimally invasive procedures (340.6 cm2 vs 259.6 cm2; p < 0.001). No difference deemed a risk factor for chronic postoperative pain was seen in the rate of preoperative pain between the open and minimally invasive procedures (Appendix Table 4) No significant differences were found in either the perioperative complications or at 1-year follow-up.

Conclusions

Incisional hernias after complex pancreatic surgery can be repaired safely and with a low recurrence rate in both open and minimally invasive techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pancreatic surgery has experienced significant medical progress in the past decades and is now characterized by much lower mortality than in the past [1,2,3]. However, morbidity is still high in patients with pancreatic resection. Wound healing disorders continue to play a significant role. Thus, this patient group per se has an increased risk of developing incisional hernias. The main indications for pancreatic resection are still malignancies and chronic pancreatitis. In the last decade, cystic neoplasms have been added as incidental findings of precancerous disease in healthy patients. The majority of elective surgical pancreatic procedures are performed in conventional open surgery. Minimally invasive procedures have gained importance in recent years. There is, therefore, a heterogeneous group in terms of comorbidities and long-term prognosis. The risk of incisional hernia described in the literature is 12–18% [4,5,6,7].

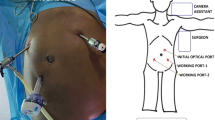

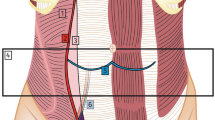

Different access techniques are used in open pancreatic surgery. This variability results from the strategy, which must be aligned with the goal of the operation [8]. Often, surgery is performed via a transverse approach, which should be guided with a 2 cm distance from the costal arch [8]. In general, there is a lower risk of developing an incisional hernia after performing a transverse laparotomy [8, 9]. However, if a hernia does occur permanent correction is difficult [10]. Compared with medial incisional hernias, lateral incisional hernias are at significantly higher risk of recurrence [11]. To prevent incisional hernia, the combination of medial and transverse laparotomy should be avoided [8]. The use of mesh augmentation for closure of lateral incisions may reduce the incidence of incisional hernias [12]. The present analysis of data from the Herniamed Register is intended, on one hand, to shed light on the problems of treating transverse incisional hernias following complex upper abdominal procedures, such as pancreatic surgery, and on the other hand to compare the outcomes of open vs minimally invasive incisional hernia repair.

Methods

The following analysis from the Herniamed Registry compares the outcomes of laparoscopic and open incisional hernia repair after pancreatic surgery. Both perioperative (intraoperative complications, postoperative complications, complication-related reoperations) and 1-year follow-up outcomes (recurrence rate, rates of pain at rest and on exertion, and chronic pain requiring treatment) have been studied.

Herniamed is an internet-based hernia registry in which hospitals and surgeons in private practice from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland can voluntarily enter their routinely performed hernia operations [10, 11]. On the cutoff date of 04 January 2023, the number of participating clinics/practices was 892 (Fig. 1). All patients signed a special informed consent form agreeing to participate in the Herniamed Registry. During the consultation for documentation in the Herniamed Registry, patients are requested to inform their treating clinic/practice about any problem after hernia surgery. If there are any problems after surgery, the patient can visit their treating clinic/practice for a clinical examination at any time. Perioperative complications are recorded up to 30 days after surgery.

After 1, 5, and 10 years, the patient and the primary care physician are sent a questionnaire asking about any pain at rest, pain on exertion, and chronic pain requiring treatment or any bulging/recurrence. Pain is graded using the visual analog scale. In addition, the patient is asked again about any perioperative complications that occurred and, if necessary, a follow-up visit is arranged [11]. If the patient or their primary care physician reports a problem at follow-up, the patient may be requested to attend the treating hospital/practice for further diagnostic measures based on clinical examination, CT, ultrasound or MRI.

The present analysis retrospectively examines the prospectively collected data of patients who underwent primary elective incisional hernia repair after previous pancreatic surgery. Open vs minimally invasive incisional hernia operations were compared.

All analyses were performed with the software SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and intentionally calculated to a full significance level of 5%, i.e., they were not corrected in respect of multiple tests, and each p value ≤ 0.05 represents a significant result. Unadjusted analyses were performed to analyze the effect of an individual influencing factor on an outcome parameter, with the main focus on the association with the surgical procedure. For a categorical outcome variable the Chi-square test was used. For continuous outcome variables, the ANOVA (analysis of variance) was used to analyze the influence of the comparison groups.

The complete results are presented in tabular form in the appendix. Relevant partial aspects are already mentioned in the Results section of the text.

Results

Data of the total group

There are 129,257 patients with incisional hernias in the Herniamed Registry as of January 04, 2023. Of these, 755 patients meet the criterion of pancreatic surgery as the only previous abdominal surgery. Relative to the total number of all patients with incisional hernias in the Herniamed Registry, this is a very small group (0.58%). 1-year follow-up information after 12 months was available for 461 patients.

In 440 patients (95%), the pancreas was operated on using the classic open technique. Minimally invasive pancreatic surgery accounts for only 5% (n = 21) of all procedures.

Most incisional hernias were 4–10 cm in size (n = 240; 52.0%) and were located medially in 310 cases (67.2%). Lateral (n = 71; 15.4%) or combined (n = 80; 17.4%) incisional hernias occurred in 151 patients (32.8%). Preoperative pain was reported in 264 (57.0%) cases. In almost a quarter (n = 114; 24.8%) of cases, the defect size was less than 4 cm. A total of 36 (7.8%) cases used mesh-free direct suture techniques. It is not possible to say why surgeons opted for a mesh-free procedure. A defect larger than 10 cm (W3, EHS classification) was found in a roughly equal group of patients (21.5% minimally invasive vs 23.6% open; p = 0.926).

Surgical techniques involving retromuscular (Sublay; n = 234; 50.8%) or intraperitoneal mesh placement (lap. and open IPOM n = 160; 34.7%) were performed in 394 (85%) cases. All other techniques were only rarely used (Tab. 1). Surprisingly, the open suture technique was used in in 7.8% (n = 36) of cases.

Previous pancreatic surgery

Only 4.5% (n = 21) of the previous pancreatic surgeries were performed in laparoscopic and 95.5% (n = 440) open technique.

Comparison of patient collectives with endoscopic and open incisional hernia repair

Of the 461 incisional hernia operations, 79 (17.1%) were performed endoscopically and 382 (82.9%) openly.

There were only a few significant differences between endoscopic and open incisional hernia repair. For example, drainage was used significantly more often in open surgery (72.8% vs 13.9%; p < 0.001), as was defect closure (58.1% vs 25.3%; p < 0.001). The mesh used was significantly smaller in open surgery than in the minimally invasive technique (259.6 cm2 vs 340.6 cm2; p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in defect sizes.

No significant difference was found between the endoscopic and open incisional hernia repairs with regard to the operation techniques based on the EHS classification for incisional hernia localization: medial, lateral and combined (Table 2).

Up to 30 days after surgery, there was no significant difference between minimally invasive and open incisional hernia surgery after previous pancreatic surgery with regard to the perioperative complication rates (intraoperative complications, general complications, postoperative complications, complication-related reoperation) (see Tables 7, 8, 9 in the Appendix). Likewise, at 1-year follow-up, no significant differences were seen between the open and minimally invasive procedures in the rates of recurrence, pain on exertion, pain at rest, and chronic pain requiring treatment (Table 3).

Discussion

In the participating countries of the Herniamed Registry (Germany, Austria, Switzerland), several thousand pancreatic procedures are performed annually. In relation to this, the number of patients with operated incisional hernias in this registry study seems very small. However, no precise figures are available on this. However, studies with larger numbers of cases often report only the occurrence of incisional hernias and their risk factors, with no information on surgical management or follow-up [5, 7, 12, 13]. It is conceivable that a relevant proportion of patients with incisional hernias after pancreatic surgery are subject to a watch and wait concept, as the hernia is not at the medical forefront.

Incisional hernia operations were performed only in 5% of patients after laparoscopic and in 95% after open prior pancreatic surgery. According to the US Nationwide Inpatient Sample database from 2000 to 2011, only 5% of all pancreatic resections were performed laparoscopically [14]. A systematic review revealed that incisional hernias occur significantly less frequently after laparoscopic abdominal surgery than after open abdominal surgery. [15]. Accordingly, efforts are being made to increase the proportion of minimally invasive pancreatic surgery cases using a surgical robot [16]. This should be able to reduce the rate of incisional hernias after pancreatic surgery.

The percentage of lateral (15.4%) and combined (17.4%) incisional hernias after pancreatic surgery is 32.8% (Table 1). Lateral and combined incisional hernias are considered complex and their treatment more difficult [8]. In addition, larger defects occur more frequently after pancreatic surgery than after other previous surgeries. For example, the percentage of incisional hernias with a defect of > 10 cm after pancreatic resection is 23.2%, while it is only 16.4% after other preoperative procedures [11]. Defects of size 4–10 cm also occur more frequently after pancreatic surgery at 52.0% compared to other abdominal surgeries at 45.9%. Based on these figures, it is clear that incisional hernia operations after previous pancreatic surgery are more difficult to treat due to the size and localization of the defects. This is then also reflected in the proportion of minimally invasive operations. While the proportion of laparoscopic incisional hernia repairs after pancreatic surgery is only 17.1%, the proportion in the total collective of primary elective incisional hernia repair is 27.8% [11].

In the comparison of the results after minimally invasive vs open incisional hernia operations after pancreatic surgery, no significant differences were found either for the perioperative results (intraoperative complications, postoperative complications, complication-related reoperation, and general complications) or at 1-year follow-up (recurrence, pain at rest, pain on exertion and chronic pain requiring treatment). However, it has to be said that in the open group the proportion of patients with defects > 10 cm, lateral and combined defect localization and ASA classification is significantly higher. Nevertheless, it seems to be possible even with minimally invasive surgery to achieve good results in the treatment of incisional hernias after such complex previous operations as surgery on the pancreas.

There are also no significant differences when compared with the results of primary elective incisional hernia surgery in other patients in the Herniamed Registry [11]. Thus, previous surgery on the pancreas with subsequent formation of an incisional hernia does not represent an argument against appropriate surgical management. The results also support a minimally invasive approach after complex surgery on the pancreas. The IPOM technique is also associated with very good results in this study. In the future, we expect an increase in component separation techniques. Except for a few findings (small medial incisional hernia), release of the transversus abdominis will always be required if adequate overlap in the extra-peritoneal plane is to be achieved. The technique is required for all lateral and combined hernias. The same is true for medial hernias with close contact to the xiphoid process. Therefore, robot-assisted surgery of incisional hernia after prior operation on the pancreas may gain increasing importance in the future [17,18,19].

A limiting factor for this study is that due to the complexity of the underlying disease, treatment of an existing hernia may often not be performed in a relevant number of cases. Consequently, only a small number of patients with an incisional hernia after previous pancreatic surgery are available for this registry study. For the follow-up, data are available for only about 61.1% of patients. The diversity in surgical techniques presented in this study constitutes a major confounding factor, thereby complicating the drawing of definitive conclusions. The 7.8% proportion with incisional hernia suture closure is problematic. A higher recurrence rate must be expected for this subgroup [11].

Conclusion

The data show that surgical management of incisional hernias after pancreatic surgery is safely feasible. At 1-year follow-up, the recurrence rate is low. After pancreatic surgery, no significant differences were found either for the perioperative results (intraoperative complications, postoperative complications, complication-related reoperation, and general complications) or for the 1-year follow-up outcomes (rates of recurrence, pain at rest, pain on exertion and chronic pain requiring treatment).

References

Gudjonsson B (1995) Carcinoma of the pancreas: critical analysis of costs, results of resections, and the need for standardized reporting. J Am Coll Surg 181(6):483–503

Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB, Staiger DO (2006) Operative mortality and procedure volume as predictors of subsequent hospital performance. Ann Surg 243(3):411–417. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000201800.45264.51

Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Batista I et al (2002) Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 346(15):1128–1137. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa012337

Aleotti F, Crippa S, Belfiori G, Tamburrino D, Partelli S, Longo E et al (2022) Pancreatic resections for benign intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: collateral damages from friendly fire. Surgery 172(4):1202–1209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2022.04.036

Chen-Xu J, Bessa-Melo R, Graça L, Costa-Maia J (2019) Incisional hernia in hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: incidence and risk factors. Hernia 23(1):67–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1847-4

Brown JA, Zenati MS, Simmons RL, Al Abbas AI, Chopra A, Smith K et al (2020) Long-term surgical complications after pancreatoduodenectomy: incidence, outcomes, and risk factors. J Gastrointest Surg 24(7):1581–1589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-020-04641-3

Davey S, Rajaretnem N, Harji D, Rees J, Messenger D, Smart NJ et al (2020) Incisional hernia formation in hepatobiliary surgery using transverse and hybrid incisions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 102(9):663–671. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsann.2020.0163

Medina Pedrique M, Valle R, de Lersundi Á, Avilés Oliveros A, Ruiz SM, López-Monclús J, Munoz-Rodriguez J et al (2023) Incisions in hepatobiliopancreatic surgery: surgical anatomy and its influence to open and close the abdomen. J Abdom Wall Surg. https://doi.org/10.3389/jaws.2023.11123

Halm JA, Lip H, Schmitz PI, Jeekel J (2009) Incisional hernia after upper abdominal surgery: a randomised controlled trial of midline versus transverse incision. Hernia 13(3):275–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-008-0469-7

Schaaf S, Willms A, Adolf D, Schwab R, Riediger H, Köckerling F (2022) What are the influencing factors on the outcome in lateral incisional hernia repair? A registry-based multivariable analysis. Hernia. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-022-02690-y

Kockerling F, Hoffmann H, Adolf D, Reinpold W, Kirchhoff P, Mayer F et al (2021) Potential influencing factors on the outcome in incisional hernia repair: a registry-based multivariable analysis of 22,895 patients. Hernia 25(1):33–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-020-02184-9

Memba R, Morato O, Estalella L, Pavel MC, Llacer-Millan E, Achalandabaso M et al (2022) Prevention of incisional hernia after open hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery: a systematic review. Dig Surg 39(1):6–16. https://doi.org/10.1159/000521169

Iida H, Tani M, Hirokawa F, Ueno M, Noda T, Takemura S et al (2021) Risk factors for incisional hernia according to different wound sites after open hepatectomy using combinations of vertical and horizontal incisions: a multicenter cohort study. Ann Gastroenterol Surg 5(5):701–710. https://doi.org/10.1002/ags3.12467

Justin V, Fingerhut A, Khatkov I, Uranues S (2016) Laparoscopic pancreatic resection—a review. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 1:36. https://doi.org/10.21037/tgh.2016.04.02

Kossler-Ebs JB, Grummich K, Jensen K, Huttner FJ, Muller-Stich B, Seiler CM et al (2016) Incisional hernia rates after laparoscopic or open abdominal surgery-a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg 40(10):2319–2330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-016-3520-3

Winer J, Can MF, Bartlett DL, Zeh HJ, Zureikat AH (2012) The current state of robotic-assisted pancreatic surgery. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 9(8):468–476. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2012.120

Kudsi OY, Bou-Ayash N, Chang K, Gokcal F (2020) Robotic repair of lateral incisional hernias using intraperitoneal onlay, preperitoneal, and retromuscular mesh placement: a comparison of mid-term results and surgical technique. Eur Surg 53(4):188–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10353-020-00634-3

Pereira X, Lima DL, Huang LC, Salas-Parra R, Shah P, Malcher F et al (2022) Robotic versus open lateral abdominal hernia repair: a multicenter propensity score matched analysis of perioperative and 1-year outcomes. Hernia. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-022-02713-8

Martin-Del-Campo LA, Weltz AS, Belyansky I, Novitsky YW (2018) Comparative analysis of perioperative outcomes of robotic versus open transversus abdominis release. Surg Endosc 32(2):840–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5752-1

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Prof. Dr. Köckerling reports grants to fund Herniamed from Johnson&Johnson, Norderstedt, Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, MenkeMed, Munich, DB Karlsruhe and personal fees from BD Karlsruhe. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Ethical approval

Only cases of routine hernia surgery were documented in the Herniamed Registry and all patients have signed a special informed consent declaration agreeing to participate. The Herniamed Registry has ethical approval (BASEC No. 2016—00.123, 287/2017 BO2).

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any Study with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

All patients with routine hernia surgery documented in Herniamed Registry have signed an informed consent declaration agreeing to participate.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Appendix Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9.

Parameters by type of access | N | NMiss | Mean | SD | Min | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Age [years] | Laparoscopic surgery | 79 | 0 | 62.3 | 11.63 | 35.0 | 53.0 | 61.0 | 73.0 | 86.0 |

Open surgery | 382 | 0 | 61.7 | 12.81 | 22.0 | 53.0 | 63.0 | 72.0 | 86.0 | |

Total | 461 | 0 | 61.8 | 12.61 | 22.0 | 53.0 | 63.0 | 72.0 | 86.0 | |

BMI [kg/m2] | Laparoscopic surgery | 79 | 0 | 27.2 | 5.25 | 17.3 | 24.3 | 26.4 | 28.7 | 49.0 |

Open surgery | 382 | 0 | 25.8 | 4.45 | 15.4 | 22.8 | 25.3 | 28.2 | 45.4 | |

Total | 461 | 0 | 26.1 | 4.62 | 15.4 | 23.0 | 25.6 | 28.3 | 49.0 | |

Duration of operation [min] | Laparoscopic surgery | 79 | 0 | 96.7 | 51.58 | 23.0 | 58.0 | 86.0 | 126.0 | 263.0 |

Open surgery | 374 | 8 | 92.1 | 52.53 | 20.0 | 56.0 | 78.0 | 120.0 | 380.0 | |

Total | 453 | 8 | 92.9 | 52.34 | 20.0 | 58.0 | 80.0 | 120.0 | 380.0 | |

Mesh size [cm2] | Laparoscopic surgery | 77 | 2 | 395.5 | 239.41 | 81.0 | 225.0 | 300.0 | 500.0 | 1500.0 |

Open surgery | 343 | 39 | 348.2 | 251.16 | 16.0 | 150.0 | 300.0 | 450.0 | 1500.0 | |

Total | 420 | 41 | 356.9 | 249.44 | 16.0 | 150.0 | 300.0 | 500.0 | 1500.0 | |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krueger, C.M., Patrzyk, M., Hipp, J. et al. Incisional hernia repair following pancreatic surgery—open vs laparoscopic approach. Hernia 28, 155–165 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-023-02901-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-023-02901-0