Abstract

Aims

Inflammation is central to the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome (MetS). Leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 (LECT2) is constitutively secreted in response to inflammatory stimuli and oxidative stress contributing to tissue or systemic inflammation. We explored the relationship between LECT2 levels and MetS severity in humans and mice.

Methods

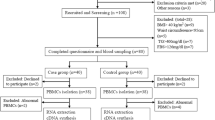

Serum LECT2 levels were measured in 210 participants with MetS and 114 without MetS (non-MetS). LECT2 expression in the liver and adipose tissue was also examined in mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) and genetically obese (ob/ob) mice.

Results

Serum LECT2 levels were significantly higher in MetS participants than in non-MetS participants (7.47[3.36–17.14] vs. 3.74[2.61–5.82], P < 0.001). Particularly, serum LECT2 levels were significantly elevated in participants with hypertension, central obesity, diabetes mellitus (DM), hyperglycaemia, elevated triglyceride (TG) levels, and reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels compared to those in participants without these conditions. Pearson’s correlation analysis showed that serum LECT2 levels were positively associated with conventional risk factors in all patients. Moreover, LECT2 was positively associated with the number of MetS components (r = 0.355, P < 0.001), indicating that higher serum LECT2 levels reflected MetS severity. Multivariate regression analysis revealed that a one standard deviation increase in LECT2 was associated with an odds ratio of 1.52 (1.01–2.29, P = 0.044) for MetS prevalence after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, waist circumference, smoking status, white blood cell count, fasting blood glucose, TG, total cholesterol, HDL-C, blood urea nitrogen, and alanine aminotransferase. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis confirmed the strong predictive ability of serum LECT2 levels for MetS. The optimum serum LECT2 cut-off value was 9.05. The area under the curve was 0.73 (95% confidence interval 0.68–0.78, P < 0.001), with a sensitivity and specificity of 45.71% and 95.61%, respectively. Additionally, LECT2 expression levels were higher at baseline and dramatically enhanced in metabolic organs (e.g. the liver) and adipose tissue in HFD-induced obese mice and ob/ob mice.

Conclusions

Increased LECT2 levels were significantly and independently associated with the presence and severity of MetS, indicating that LECT2 could be used as a novel biomarker and clinical predictor of MetS.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The information and data of the study population were extracted from Hospital Information System.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- H&E:

-

Haematoxylin and eosin

- HFD:

-

High-fat diet

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- ISH:

-

Isolated systolic hypertension

- LECT2:

-

Leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- MetS:

-

Metabolic syndrome

- NCD:

-

Normal chow diet

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SEM:

-

Standard error of the mean

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- WAT:

-

White adipose tissue

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

References

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, Spertus JA, Costa F (2005) American heart association, national heart, lung, and blood institute, diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American heart association/national heart, lung, and blood institute scientific statement. Circulation 112:2735–2752. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404

Wu XY, Lin L, Qi HY, Du R, Hu CY, Ma LN, Peng K, Li M, Xu Y, Xu M, Chen YH, Lu JL, Bi YF, Wang WQ, Ning G (2019) Association between lipoprotein (a) levels and metabolic syndrome in a middle-aged and elderly chinese cohort. Biomed Environ Sci 32:477–485. https://doi.org/10.3967/bes2019.065

Zhong L, Liu J, Liu S, Tan G (2023) Correlation between pancreatic cancer and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 14:1116582. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1116582

Kim J, Han K, Kim MK, Baek K-H, Song K-H, Kwon H-S (2023) Cumulative exposure to metabolic syndrome increases thyroid cancer risk in young adults: a population-based cohort study. Korean J Intern Med. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2022.405

Yin L, Li S, He Y, Yang L, Wang L, Li C, Wang Y, Wang J, Yang P, Wang J, Chen Z, Li Y (2023) Impact of urinary sodium excretion on the prevalence and incidence of metabolic syndrome: a population-based study. BMJ Open 13:e065402. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065402

Hirode G, Wong RJ (2020) Trends in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the United States, 2011–2016. JAMA 323:2526–2528. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4501

Saklayen MG (2018) The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep 20:12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-018-0812-z

O’Neill S, O’Driscoll L (2015) Metabolic syndrome: a closer look at the growing epidemic and its associated pathologies. Obes Rev 16:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12229

Do Vale Moreira NC, Hussain A, Bhowmik B, Mdala I, Siddiquee T, Fernandes VO, Júnior RM, Meyer HE (2020) Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome by different definitions, and its association with type 2 diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular disease risk in Brazil. Diabetes Metab Syndr 14:1217–1224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.043

Ranasinghe P, Mathangasinghe Y, Jayawardena R, Hills AP, Misra A (2017) Prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome among adults in the asia-pacific region: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 17:101. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4041-1

Fatima SS, Jamil Z, Abidi SH, Nadeem D, Bashir Z, Ansari A (2017) Interleukin-18 polymorphism as an inflammatory index in metabolic syndrome: a preliminary study, World. J Diabetes 8:304–310. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v8.i6.304

Matsubayashi Y, Fujihara K, Yamada-Harada M, Mitsuma Y, Sato T, Yaguchi Y, Osawa T, Yamamoto M, Kitazawa M, Yamada T, Kodama S, Sone H (2022) Impact of metabolic syndrome and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease on cardiovascular risk by the presence or absence of type 2 diabetes and according to sex. Cardiovasc Diabetol 21:90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-022-01518-4

Yoo HJ, Hwang SY, Choi J-H, Lee HJ, Chung HS, Seo J-A, Kim SG, Kim NH, Baik SH, Choi DS, Choi KM (2017) Association of leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 (LECT2) with NAFLD, metabolic syndrome, and atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE 12:e0174717. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174717

Yamagoe S, Yamakawa Y, Matsuo Y, Minowada J, Mizuno S, Suzuki K (1996) Purification and primary amino acid sequence of a novel neutrophil chemotactic factor LECT2. Immunol Lett 52:9–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-2478(96)02572-2

Hiraki Y, Inoue H, Kondo J, Kamizono A, Yoshitake Y, Shukunami C, Suzuki F (1996) A novel growth-promoting factor derived from fetal bovine cartilage, chondromodulin II. Purification and amino acid sequence. J Biol Chem 271:22657–22662. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.271.37.22657

Xu M, Xu H-H, Lin Y, Sun X, Wang L-J, Fang Z-P, Su X-H, Liang X-J, Hu Y, Liu Z-M, Cheng Y, Wei Y, Li J, Li L, Liu H-J, Cheng Z, Tang N, Peng C, Li T, Liu T, Qiao L, Wu D, Ding Y-Q, Zhou W-J (2019) LECT2, a Ligand for Tie1, plays a crucial role in liver fibrogenesis. Cell 178:1478-1492.e20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.07.021

Lu X-J, Chen J, Yu C-H, Shi Y-H, He Y-Q, Zhang R-C, Huang Z-A, Lv J-N, Zhang S, Xu L (2013) LECT2 protects mice against bacterial sepsis by activating macrophages via the CD209a receptor. J Exp Med 210:5–13. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20121466

Takata N, Ishii K-A, Takayama H, Nagashimada M, Kamoshita K, Tanaka T, Kikuchi A, Takeshita Y, Matsumoto Y, Ota T, Yamamoto Y, Yamagoe S, Seki A, Sakai Y, Kaneko S, Takamura T (2021) LECT2 as a hepatokine links liver steatosis to inflammation via activating tissue macrophages in NASH. Sci Rep 11:555. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80689-0

Xie Y, Zhong K-B, Hu Y, Xi Y-L, Guan S-X, Xu M, Lin Y, Liu F-Y, Zhou W-J, Gao Y (2022) Liver infiltration of multiple immune cells during the process of acute liver injury and repair. World J Gastroenterol 28:6537–6550. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i46.6537

Xie Y, Fan K-W, Guan S-X, Hu Y, Gao Y, Zhou W-J (2022) LECT2: A pleiotropic and promising hepatokine, from bench to bedside. J Cell Mol Med 26:3598–3607. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.17407

He W-M, Dai T, Chen J, Wang J-A (2019) Leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 inhibits development of atherosclerosis in mice. Zool Res 40:317–323. https://doi.org/10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2019.030

Zhang Z, Zeng H, Lin J, Hu Y, Yang R, Sun J, Chen R, Chen H (2018) Circulating LECT2 levels in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus and their association with metabolic parameters. Medicine (Baltimore) 97:e0354. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000010354

Kim J, Lee SK, Kim D, Lee E, Park CY, Choe H, Kang M-J, Kim HJ, Kim J-H, Hong JP, Lee YJ, Park HS, Heo Y, Jang YJ (2022) Adipose tissue LECT2 expression is associated with obesity and insulin resistance in Korean women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 30:1430–1441. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23445

Lan F, Misu H, Chikamoto K, Takayama H, Kikuchi A, Mohri K, Takata N, Hayashi H, Matsuzawa-Nagata N, Takeshita Y, Noda H, Matsumoto Y, Ota T, Nagano T, Nakagen M, Miyamoto K, Takatsuki K, Seo T, Iwayama K, Tokuyama K, Matsugo S, Tang H, Saito Y, Yamagoe S, Kaneko S, Takamura T (2014) LECT2 functions as a hepatokine that links obesity to skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Diabetes 63:1649–1664. https://doi.org/10.2337/db13-0728

Greenow KR, Zverev M, May S, Kendrick H, Williams GT, Phesse T, Parry L (2018) Lect2 deficiency is characterised by altered cytokine levels and promotion of intestinal tumourigenesis. Oncotarget 9:36430–36443. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.26335

Sangaraju SL, Yepez D, Grandes XA, Talanki Manjunatha R, Habib S (2022) Cardio-metabolic disease and polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS): a narrative review. Cureus 14:e25076. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.25076

Yang L, Cao C, Kantor ED, Nguyen LH, Zheng X, Park Y, Giovannucci EL, Matthews CE, Colditz GA, Cao Y (2019) Trends in sedentary behavior among the US population, 2001–2016. JAMA 321:1587–1597. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.3636

Ahmed M, Kumari N, Mirgani Z, Saeed A, Ramadan A, Ahmed MH, Almobarak AO (2022) Metabolic syndrome definition, pathogenesis, elements, and the effects of medicinal plants on it’s elements. J Diabetes Metab Disord 21:1011–1022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-021-00965-2

Kuzan A, Maksymowicz K, Królewicz E, Lindner-Pawłowicz K, Zatyka P, Wojnicz P, Nowaczyński M, Słomczyński A, Sobieszczańska M (2023) Association between leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 and metabolic and renal diseases in a geriatric population: a pilot study. J Clin Med 12:7544. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12247544

Kameoka Y, Yamagoe S, Hatano Y, Kasama T, Suzuki K (2000) Val58Ile polymorphism of the neutrophil chemoattractant LECT2 and rheumatoid arthritis in the Japanese population. Arthritis Rheum 43:1419–1420. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(200006)43:6%3c1419::AID-ANR28%3e3.0.CO;2-I

Wang Q, Xu F, Chen J, Xie Y-Q, Xu S-L, He W-M (2023) Serum Leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 (LECT2) level is associated with osteoporosis. Lab Med 54:106–111. https://doi.org/10.1093/labmed/lmac080

Qin J, Sun W, Zhang H, Wu Z, Shen J, Wang W, Wei Y, Liu Y, Gao Y, Xu H (2022) Prognostic value of LECT2 and relevance to immune infiltration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Genet 13:951077. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.951077

Lin Y, Dong M-Q, Liu Z-M, Xu M, Huang Z-H, Liu H-J, Gao Y, Zhou W-J (2022) A strategy of vascular-targeted therapy for liver fibrosis. Hepatology 76:660–675. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.32299

de la Cruz Jasso MA, Mejía-Vilet JM, Del Toro-Cisneros N, Aguilar-León DE, Morales-Buenrostro LE, Herrera G, Uribe-Uribe NO (2023) Leukocyte chemotactic factor 2 amyloidosis (ALECT2) distribution in a mexican population. Am J Clin Pathol 159:89–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqac138

Spahis S, Borys J-M, Levy E (2017) Metabolic syndrome as a multifaceted risk factor for oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal 26:445–461. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2016.6756

Vona R, Gambardella L, Cittadini C, Straface E, Pietraforte D (2019) Biomarkers of oxidative stress in metabolic syndrome and associated diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019:8267234. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8267234

Rezzani R, Franco C (2021) Liver, oxidative stress and metabolic syndromes. Nutrients 13:301. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020301

Esser N, Legrand-Poels S, Piette J, Scheen AJ, Paquot N (2014) Inflammation as a link between obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 105:141–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2014.04.006

Després J-P (2006) Is visceral obesity the cause of the metabolic syndrome? Ann Med 38:52–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890500383895

Kong Q, Zou J, Zhang Z, Pan R, Zhang ZY, Han S, Xu Y, Gao Y, Meng Z-X (2022) BAF60a deficiency in macrophage promotes diet-induced obesity and metabolic inflammation. Diabetes 71:2136–2152. https://doi.org/10.2337/db22-0114

Blüher M, Bashan N, Shai I, Harman-Boehm I, Tarnovscki T, Avinaoch E, Stumvoll M, Dietrich A, Klöting N, Rudich A (2009) Activated Ask1-MKK4-p38MAPK/JNK stress signaling pathway in human omental fat tissue may link macrophage infiltration to whole-body Insulin sensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:2507–2515. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2009-0002

Shen HX, Li L, Chen Q, He YQ, Yu CH, Chu CQ, Lu XJ, Chen J (2016) LECT2 association with macrophage-mediated killing of Helicobacter pylori by activating NF-κB and nitric oxide production. Genet Mol Res 15:gmr15048889. https://doi.org/10.4238/gmr15048889

Jung TW, Chung YH, Kim H-C, Abd El-Aty AM, Jeong JH (2018) LECT2 promotes inflammation and insulin resistance in adipocytes via P38 pathways. J Mol Endocrinol 61:37–45. https://doi.org/10.1530/JME-17-0267

Rao K-R, Bao R-Y, Ming H, Liu J-W, Dong Y-F (2023) The correlation between aldosterone and leukocyte-related inflammation: a comparison between patients with primary aldosteronism and essential hypertension. J Inflamm Res 16:2401–2413. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S409146

Zhang X, Sun K, Tang C, Cen L, Li S, Zhu W, Liu P, Chen Y, Yu C, Li L (2023) LECT2 modulates dendritic cell function after Helicobacter pylori infection via the CD209a receptor. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 38:625–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.16138

Hwang H-J, Jung TW, Hong HC, Seo JA, Kim SG, Kim NH, Choi KM, Choi DS, Baik SH, Yoo HJ (2015) LECT2 induces atherosclerotic inflammatory reaction via CD209 receptor-mediated JNK phosphorylation in human endothelial cells. Metabolism 64:1175–1182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2015.06.001

Inhibition of VEGF165/VEGFR2-dependent signaling by LECT2 suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma angiogenesis - PMC, (n.d.). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4979047/ (accessed May 27, 2023)

Okumura A, Unoki-Kubota H, Matsushita Y, Shiga T, Moriyoshi Y, Yamagoe S, Kaburagi Y (2013) Increased serum leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 (LECT2) levels in obesity and fatty liver. Biosci Trends 7:276–283

Li L, Xiong Y-L, Tu B, Liu S-Y, Zhang Z-H, Hu Z, Yao Y (2023) Effect of renal denervation for patients with isolated systolic hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Geriatr Cardiol 20:121–129. https://doi.org/10.26599/1671-5411.2023.02.003

Gao L-W, Huang Y-W, Cheng H, Wang X, Dong H-B, Xiao P, Yan Y-K, Shan X-Y, Zhao X-Y, Mi J (2023) Prevalence of hypertension and its associations with body composition across Chinese and American children and adolescents. World J Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-023-00740-8

Tsai T-Y, Cheng H-M, Chuang S-Y, Chia Y-C, Soenarta AA, Minh HV, Siddique S, Turana Y, Tay JC, Kario K, Chen C-H (2021) Isolated systolic hypertension in Asia. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 23:467–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.14111

Grebla RC, Rodriguez CJ, Borrell LN, Pickering TG (2010) Prevalence and determinants of isolated systolic hypertension among young adults: the 1999–2004 US National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey. J Hypertens 28:15–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e328331b7ff

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the project of National Nature Science Foundation of China (NSFC), No. 82171557, and the Excellent Youth Foundation of Hunan Scientific Committee, No. 2021JJ20085.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XL.Z, JM.L, P.Z, and YH.H contributed to the conception or design of the work. XL.Z, P.Z, H.C, C.Z, and SJ.X were responsible for the acquisition, analysis of data. XL.Z was the major contributor to the manuscript. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content was performed by all authors. All author agreed with the content of the article to be submitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Second Xiangya Hospital (number: 20240025) and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki principles. All participants signed informed consent before their inclusion in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Managed by Antonio Secchi.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, X., Lu, J., Xiang, S. et al. Elevated serum levels of leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 are associated with the prevalence of metabolic syndrome. Acta Diabetol 61, 643–655 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-024-02242-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-024-02242-z