Abstract

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of ticagrelor versus prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) presenting during off- and on-hours.

Background

The efficacy and safety of ticagrelor versus prasugrel in patients with ACS according to time of hospital presentation remain unknown.

Methods

This post hoc analysis of the ISAR-REACT 5 trial included 1565 patients with ACS presenting off-hours and 2453 patients presenting on-hours, randomized to ticagrelor or prasugrel. The primary endpoint was a composite of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke; the safety endpoint was Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 3–5 bleeding, both at 12 months.

Results

The primary endpoint occurred in 80 patients (10.4%) in the ticagrelor group and 57 patients (7.3%) in the prasugrel group in patients presenting off-hours (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.45; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.03–2.03; P = 0.033), and 104 patients (8.5%) in the ticagrelor group and 80 patients (6.7%) in the prasugrel group in patients presenting on-hours (HR = 1.29 [0.97–1.73]; P = 0.085), without significant treatment arm-by-presentation time interaction (Pint = 0.62). BARC type 3 to 5 bleeding occurred in 35 patients (5.1%) in the ticagrelor group and 37 patients (5.3%) in the prasugrel group (P = 0.84) in patients presenting off-hours, and 60 patients (5.9%) in the ticagrelor group and 43 patients (4.6%) in the prasugrel group in patients presenting on-hours (P = 0.17).

Conclusions

In patients with ACS planned to undergo an invasive treatment strategy, time of presentation (off-hours vs. on-hours) does not interact significantly with the relative efficacy and safety of ticagrelor vs. prasugrel.

Clinical trial registration.

NCT01944800.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Several studies have reported higher in-hospital and long-term mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) presenting during off-hours [1,2,3]. A shortage of specialized staff [4], lower use of cardiac invasive procedures [1], and longer door-to-balloon times [5, 6] have been reported during off-hour admission, suggesting a worse quality of care in patients presenting to the hospital during off-hours and stressing the need for powerful antiplatelet drugs in these patients. Prasugrel and ticagrelor—the newer P2Y12 inhibitors—provide more potent and consistent platelet inhibition compared with clopidogrel and randomized clinical trials have demonstrated an advantage of these drugs over clopidogrel and of prasugrel over ticagrelor in reducing the ischemic risk in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [7,8,9]. Patients presenting with acute MI during off-hours have a worse cardiovascular risk profile [3, 10, 11] and these patients may especially benefit from potent platelet inhibition with prasugrel [9]. On the other hand, the standard twice daily administration of ticagrelor might be more advantageous compared with the once daily administration of prasugrel in overcoming the periods of increased platelet reactivity and aggregation during the early morning hours [12,13,14]. Evidence suggests that while platelet inhibition with prasugrel in patients with ACS does not follow a circadian pattern [13], platelet inhibition with ticagrelor might be subject to circadian variations in healthy subjects [15]. In this regard, it is largely unexplored whether the time of day at hospital presentation affects the efficacy and safety of ticagrelor versus prasugrel in patients with ACS managed with an invasive treatment strategy. We undertook this study to investigate whether there are differences in 1-year clinical outcomes between ACS patients treated with ticagrelor and prasugrel planned to undergo an invasive treatment strategy, who presented during off-hours and on-hours.

Materials and methods

Patients

This study assessed the efficacy and safety of ticagrelor versus prasugrel in patients with ACS according to off-hour versus on-hour presentation to hospital. The study is a post hoc analysis of the Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (ISAR-REACT 5) trial (Clinical Trial Registration: NCT01944800) [9]. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are reported in the primary publication [9]. In brief, patients hospitalized for ACS (unstable angina, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [NSTEMI], and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI]) planned to undergo an invasive management strategy were included. Patients were randomized to receive ticagrelor (a loading dose of 180 mg as soon as possible after randomization and a maintenance dose of 90 mg twice daily) or prasugrel (a loading dose of 60 mg and a maintenance dose of 10 mg once daily). In patients with NSTE-ACS, the loading dose of prasugrel was given after coronary anatomy was known (i.e., with no pre-treatment before diagnostic coronary angiography) and before proceeding to PCI. In patients with STEMI, prasugrel was given as soon as possible after randomization. In patients ≥ 75 years of age or those with a body weight < 60 kg (irrespective of age), a reduced maintenance dose of prasugrel (5 mg) was recommended [16]. Aspirin therapy included a loading dose of 150–300 mg intravenous or chewed aspirin and a maintenance dose of 75–100 mg daily in both ticagrelor and prasugrel arms. Dual antiplatelet therapy was recommended for at least 1 year. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee at each participating center. The study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Definitions and outcomes

Regular hours (on-hours) were defined as weekdays (Monday to Friday) from 8 AM to 5 PM. Off-hours were defined as night shift hours (from > 5 PM to < 8 AM), weekends, and local holidays [17]. Differences between the recruitment centers in defining on-hours and off-hours periods were also considered. Based on the time of presentation to hospital, patients were categorized in two groups: those presenting off-hours (n = 1565) and those presenting on-hours (n = 2453).

The primary (efficacy) endpoint was a composite of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke at 12 months after randomization. The safety endpoint was the incidence of bleeding types 3–5 according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) at 12 months after randomization. Other endpoints analyzed were the individual components of the primary endpoint, the incidence of cardiovascular death, and stent thrombosis (definite or probable) at 12 months after randomization. Detailed definitions of the study endpoints are provided in the primary publication [9].

Follow-up

Clinical follow-up was scheduled at 1 month, 6 months, and 1 year after randomization. Patients were contacted by telephone, hospital or outpatient visit, or structured follow-up letter. In case of potential endpoint-related adverse events, source data were solicited. All serious adverse events and efficacy and safety endpoints were monitored on site. In addition, 100% of source data were checked in at least 10% of patients at all centers.

Statistical analysis

The present analysis was not pre-specified in the study protocol; therefore, it represents a post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Continuous data are presented as mean ± SD or median (with 25th–75th percentiles) and were compared using either Student’s t test or the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical variables are presented as counts and proportions, and were compared using the Chi-squared test. The cumulative incidence of the primary endpoint and all-cause death according to study drug (ticagrelor or prasugrel) in patients arriving off-hours versus those arriving on-hours was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and the inter-group comparisons were performed using the Cox proportional hazard model. The participating center and stratification according to clinical presentation (ACS with or without ST-segment elevation) were entered into the Cox proportional hazards model as covariates along with study treatment group. For all endpoints, except the primary endpoint and all-cause death, the cumulative incidence functions were computed to account for competing risk. To estimate the interaction between the treatment arm and the time of presentation with respect to study endpoints, an interaction term was entered into the Cox proportional hazards models. Risk estimates are presented as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The efficacy endpoint was analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principle including all patients as initially assigned irrespective of the actual treatment received. The safety endpoint of bleeding was analyzed in a modified intention-to-treat population (including all patients with at least one application of the study drug, with bleeding assessed for up to 7 days after discontinuation of the study drug). Patients were analyzed from randomization until death, withdrawal of consent, or last contact date. Statistical analysis was performed using the R, version 3.6.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Baseline data in patients presenting during off-hours and on-hours

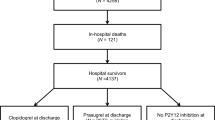

Of the 4018 patients with ACS, 1565 patients (39%) presented during off-hours and 2453 patients (61%) presented during on-hours (Supplemental Fig. S1). Baseline characteristics are shown in Supplemental Table S1. Patients presenting off-hours were younger, had a higher proportion of smokers, and were more likely to present with STEMI and develop cardiogenic shock. Patients presenting on-hours had a higher proportion of patients with diabetes (including those on insulin therapy), arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, prior PCI, and prior coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). They had more often a body weight < 60 kg, presented more often with unstable angina and NSTEMI, and were more likely to undergo conservative treatment or CABG than patients presenting off-hours.

Diagnostic coronary angiography was performed in 4004 patients (99.7%). Patients presenting off-hours were more likely to have vascular access via femoral artery, had a higher proportion of patients with single vessel disease, and a lower left-ventricular ejection fraction than patients presenting on-hours (Supplemental Table S2). Patients presenting off-hours had more often TIMI flow grades of 0, 1, and 2 before intervention, and a longer mean total stented length (31.9 mm vs. 29.6 mm; P < 0.001). Patients presenting on-hours were more likely to have received peri-procedural unfractionated heparin (Supplemental Table S3). Therapy at discharge is shown in Supplemental Table S4. Patients presenting during off-hours were more likely to be discharged on aspirin, prasugrel, and statin therapy than patients presenting during on-hours.

Baseline data according to study drugs in patients presenting during off-hours and on-hours

In the off-hour group, 778 patients were assigned to ticagrelor and 787 patients to prasugrel. In the on-hour group, 1234 patients were assigned to ticagrelor and 1219 patients to prasugrel. Baseline data are shown in Table 1. In the off-hour group, baseline characteristics did not differ significantly according to study drug (ticagrelor or prasugrel), with the exception of the proportions of patients with active smoking and cardiogenic shock (higher proportions of prasugrel-assigned patients had these conditions). In the on-hour group, baseline characteristics were well-balanced, with no statistically significant differences according to study drug.

Angiographic (Supplemental Table S5), procedural (Supplemental Table S6) data, and drug therapy at discharge (Supplemental Table S7) appear to differ little between ticagrelor- and prasugrel-assigned patients presenting during off-hours and on-hours.

Clinical outcomes

The follow-up was complete in all but 90 patients (2.2%): 32 patients presenting during off-hours and 58 patients presenting during on-hours (2.0% vs. 2.4%, respectively; P = 0.50). The primary endpoint (death, myocardial infarction, or stroke at 1 year after randomization) occurred in 137 patients presenting off-hours and 184 patients presenting on-hours (cumulative incidence 8.9% vs. 7.6%, respectively; hazard ratio [HR] = 1.18, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.94–1.47; P = 0.15; Supplemental Fig. S2, left panel). The probable and definite stent thrombosis (1.7% vs. 0.8%; P = 0.015), and definite stent thrombosis (1.2% vs. 0.6%; P = 0.044) were more frequent in patients presenting off-hours than those presenting on-hours. Clinical outcomes according to presentation during off-hours and on-hours are shown in Supplemental Table S8.

Clinical outcomes according to study drug are shown in Table 2. In patients presenting off-hours, the primary endpoint occurred in 80 patients in the ticagrelor group and 57 patients in the prasugrel group (cumulative incidence 10.4% and 7.3%, respectively; HR = 1.45 [1.03–2.03]; P = 0.033; (Fig. 1, left panel). In patients presenting on-hours, the primary endpoint occurred in 104 patients in the ticagrelor group and 80 patients in the prasugrel group (cumulative incidence 8.5% and 6.7%, respectively; HR = 1.29 [0.97–1.73]; P = 0.085; Fig. 1, right panel). There was no significant treatment arm-by-presentation time interaction with respect to primary outcome (P for interaction = 0.62).

One-year cumulative incidence of the primary endpoint (death, myocardial infarction, or stroke). Left panel: the incidence of the primary endpoint in patients presenting during off-hours. Right panel: the incidence of the primary endpoint in patients presenting during on-hours. Primary endpoint was evaluated in the intention-to-treat population CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio

In patients presenting off-hours, the incidence of definite stent thrombosis was lower in the prasugrel arm than in the ticagrelor arm (0.5% vs. 1.9%; P = 0.017). In patients presenting on-hours, there were numerically fewer deaths in the prasugrel arm (3.2% vs. 4.4%; P = 0.11) than in patients in the ticagrelor arm (Table 2).

Bleeding events

Bleeding events according to presenting hours are shown in Supplemental Table S8. BARC 3–5 bleeding occurred in 88 patients presenting off-hours and 138 patients presenting on-hours (cumulative incidence 5.7% and 5.7%; HR = 1.01 [0.77–1.32]; P = 0.95; Supplemental Fig. S2, right panel). With regard to study drug, in patients presenting off-hours, BARC 3–5 bleeding occurred in 35 patients in the ticagrelor group and 37 patients in the prasugrel group (cumulative incidence 5.1% vs. 5.3%; HR = 0.95 [0.60–1.51]; P = 0.84; Fig. 2, left panel). In patients presenting on-hours, BARC 3–5 bleeding occurred in 60 patients in the ticagrelor group and 43 patients in the prasugrel group (cumulative incidence 5.9% vs. 4.6%; HR = 1.31 [0.89–1.94]; P = 0.17; Fig. 2, right panel). There was no treatment arm-by-presentation time interaction regarding the occurrence of BARC type 3 to 5 bleeding (p for interaction = 0.30). Individual classes of bleeding according to ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients presenting off-hours and on-hours are shown in Table 2.

Cumulative incidence of the secondary safety endpoint (1-year incidence of Bleeding Academic Research Consortium type 3–5 bleeding). BARC type 3–5 bleeding was evaluated in the modified intention-to-treat population after accounting for the competing risk of death. Results are presented for patients presenting during off-hours (left panel) and on-hours (right panel). BARC Bleeding Academic Research Consortium, CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio

Discussion

In this study, we assessed whether there are differences in the efficacy and safety of ticagrelor versus prasugrel in patients with ACS treated with an invasive treatment strategy, according to off-hour versus on-hour presentation to hospital. The main findings of the study may be summarized as follows: (1) the efficacy of ticagrelor versus prasugrel appears not to differ according to time of hospital arrival; the reduction in the 12-month incidence of ischemic events by prasugrel compared with ticagrelor was consistent among patients presenting during off-and on-hours, albeit with different risk estimates. (2) Therapy with ticagrelor or prasugrel appears to be associated with a similar risk of bleeding regardless of presentation time.

Several studies have investigated the potential impact of arrival times and optimal timing of invasive PCI on outcomes of patients with ACS (STEMI, NSTEMI or both). A subgroup analysis of the Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction (HORIZONS-AMI) trial showed longer “door-to-balloon” and total ischemic times in STEMI patients presenting during off-hours (50.6%) compared with patients presenting on-hours. However, these longer time intervals did not affect any clinical outcome at follow-up, but their impact on the efficacy of drugs, such as bivalirudin, unfractionated heparin, or GPI, was not investigated [5].

The American Heart Association (AHA) “Get With The Guidelines–Coronary Artery Disease” (GWTG-CAD) registry evaluated the impact of arrival time on the care and outcomes of 93,595 patients with ACS treated in 379 hospitals between July 2000 and September 2005 [10]. In the final analysis cohort (n = 62,814 patients; 32.3% with STEMI and 67.7% with NSTEMI), 46% of patients presented during regular hours, and 54% of patients presented during off-hours. Despite slightly lower rates of primary PCI and revascularization and longer door-to-balloon times during the initial hospitalization in patients presenting during off-hours, in-hospital mortality was similar in both patient groups [10]. A 2014 meta-analysis with a total of 1,892,424 patients with ACS from the United States, Canada, and Europe [6], and a subsequent retrospective study [18] demonstrated that patients with ACS presenting during off-hours had higher in-hospital and 30-day mortality than patients presenting during on-hours and this difference was even larger in patients with STEMI [6, 18]. A number of factors that may underlie a worse prognosis in patients with ACS presenting off-hours compared with patients presenting on-hours have been suggested. Thus, walk-in or self-transported patients with ACS [19, 20], absence of digital prehospital ECG transfer [21], insufficient centralized EMS networking [22], lack of patient awareness programs [23], resource constrained hospitals [24], slow initial triage, absence of dedicated in-hospital pathways [25], major complications such as those related to emergency CABG surgery, ventricular tachyarrhythmias, stroke or transient ischemic attack, bleedings from gastrointestinal, retroperitoneal, or intracranial origin [18], higher amount of contrast use and associated contrast-induced nephropathy [26], socioeconomic differences in between the countries and regions [6], fatigue of medical staff and varying expertise of the individual PCI operators, and circadian variation in myocardial perfusion and increased reperfusion times have been suggested.

The ISAR-REACT 5 trial recruited patients predominantly from the urban areas in Germany (18 different cities) and Italy (Florence and Frosinone). In Germany, there is a widespread standardized and well-established emergency network to optimally supply patients with ACS. The dedicated German chest pain unit network has been reported to ensure rapid and structured prehospital and in-hospital care and may compensate for longer door-to-balloon times during off-hour presentation by shortening symptom-to-admission or symptom-to-first medical contact time intervals [23, 25]. Likewise, in Italy, efficient networks to guarantee efficient reperfusion therapies for patients with ACS have shown comparable clinical effectiveness both during off-hours and regular hours [27].

The current study showed that prasugrel was superior to ticagrelor (both on top of aspirin) in terms of prevention of ischemic events at 1 year in patients with ACS, regardless of presentation during off-hours or on-hours. Importantly, there were no significant differences in the risk for bleeding between the drugs in patients presenting off-hours and on-hours. The present study may be the first to demonstrate the beneficial prognostic impact of the guideline-recommended pharmacotherapy in patients with ACS undergoing invasive treatment and presenting off-hours. Thus, our data suggest that prasugrel may outbalance or even overcome the described healthcare system- and staff-related factors associated with a worse prognosis in patients with ACS who present to hospital during off-hours.

Reasons why prasugrel showed a somewhat better efficacy in patients presenting off-hours remain unknown. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of P2Y12 antagonists and on-treatment platelet reactivity with P2Y12 antagonists are potentially influenced by sex, body weight, chronic kidney disease, genetics, smoking, diabetes, body mass, inflammation, and drug–drug interactions [28, 29]. Although clear differences in the cardiovascular risk profile with a differential impact on the efficacy and safety of prasugrel or ticagrelor in patients presenting off-hours or on-hours were not observed, an influence of these factors cannot entirely be excluded. Patients presenting off-hours were more likely to have been treated with PCI. Since prasugrel may be particularly advantageous in protecting from ischemic events in patients with ACS after PCI, this could explain, at least partially, the better efficacy of the drug in patients with ACS presenting off-hours. The finding that prasugrel reduced significantly the incidence of definite stent thrombosis in patients presenting off-hours seems to support this contention.

In addition, adherence to medication may have contributed to the differences in the primary outcome of patients with ACS presenting during off-hours who were assigned to ticagrelor. Non-adherence to cardiovascular (poly-) pharmacotherapies is a common finding [28], and it has recently been described for antihypertensive drugs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, statins, and P2Y12 inhibitors following index ACS events [29,30,31]. In the ISAR-REACT 5 trial, the frequency of drug discontinuation was significantly higher for ticagrelor than prasugrel [9]. In the current analysis, prasugrel was more commonly prescribed at discharge in patients presenting off-hours than those presenting on-hours. Thus, poorer adherence to ticagrelor and/or more frequent prescription of prasugrel in patients presenting off-hours may have contributed to differences in definite stent thrombosis between the drugs.

Limitations

This study is a non-pre-specified analysis of a randomized trial. Thus, categorization of patients in groups according to time of hospital presentation reduces the study power to reliably prove the superior efficacy of prasugrel or ticagrelor in terms of reduction of ischemic events according to presentation during off-hours or on-hours. In this regard, current findings should be seen as exploratory or hypothesis-generating. Furthermore, the differences in timing of loading of prasugrel (after diagnostic coronary angiography in patients with NSTEMI and unstable angina) may have influenced the risk for bleeding [32]. Finally, this study does not provide mechanistic information as to whether there are differences in pharmacokinetic profiles of prasugrel or ticagrelor related to differences in the baseline risk or ischemia time intervals in patients with ACS presenting off-hours or on-hours.

Conclusions

In patients with ACS planned to undergo an invasive treatment strategy, time of presentation (off-hours vs. on-hours) does not interact significantly with the relative efficacy and safety of ticagrelor vs. prasugrel. The reduction in the 12-month incidence of ischemic events by prasugrel compared with ticagrelor was consistent regardless of presentation during off-hours or on-hours, albeit with different risk estimates. The risk for bleeding appears to be similar between ticagrelor and prasugrel, regardless of presentation time.

References

Kostis WJ, Demissie K, Marcella SW, Shao YH, Wilson AC, Moreyra AE, Myocardial Infarction Data Acquisition System (MIDAS 10) Study Group (2007) Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 356(1099):1109

Kruth P, Zeymer U, Gitt A, Junger C, Wienbergen H, Niedermeier F, Glunz HG, Senges J, Zahn R (2008) Influence of presentation at the weekend on treatment and outcome in ST-elevation myocardial infarction in hospitals with catheterization laboratories. Clin Res Cardiol 97:742–747

Magid DJ, Wang Y, Herrin J, McNamara RL, Bradley EH, Curtis JP, Pollack CV Jr, French WJ, Blaney ME, Krumholz HM (2005) Relationship between time of day, day of week, timeliness of reperfusion, and in-hospital mortality for patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA 294:803–812

Angus DC, Shorr AF, White A, Dremsizov TT, Schmitz RJ, Kelley MA, Committee on Manpower for Pulmonary and Critical Care Societies (COMPACCS) (2006) Critical care delivery in the United States: distribution of services and compliance with leapfrog recommendations. Crit Care Med 34:1016–1024

Cubeddu RJ, Palacios IF, Blankenship JC, Horvath SA, Xu K, Kovacic JC, Dangas GD, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, Kornowski R, Dudek D, Stone GW, Mehran R (2013) Outcome of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention during on- versus off-hours (a Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction [HORIZONS-AMI] trial substudy). Am J Cardiol 111:946–954

Sorita A, Ahmed A, Starr SR, Thompson KM, Reed DA, Prokop L, Shah ND, Murad MH, Ting HH (2014) Off-hour presentation and outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 348:f7393

Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, Horrow J, Husted S, James S, Katus H, Mahaffey KW, Scirica BM, Skene A, Steg PG, Storey RF, Harrington RA, Investigators PLATO, Freij A, Thorsen M (2009) Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 361:1045–1057

Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, Neumann FJ, Ardissino D, De Servi S, Murphy SA, Riesmeyer J, Weerakkody G, Gibson CM, Antman EM (2007) TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 357:2001–2015

Schupke S, Neumann FJ, Menichelli M, Mayer K, Bernlochner I, Wohrle J, Richardt G, Liebetrau C, Witzenbichler B, Antoniucci D, Akin I, Bott-Flugel L, Fischer M, Landmesser U, Katus HA, Sibbing D, Seyfarth M, Janisch M, Boncompagni D, Hilz R, Rottbauer W, Okrojek R, Mollmann H, Hochholzer W, Migliorini A, Cassese S, Mollo P, Xhepa E, Kufner S, Strehle A, Leggewie S, Allali A, Ndrepepa G, Schuhlen H, Angiolillo DJ, Hamm CW, Hapfelmeier A, Tolg R, Trenk D, Schunkert H, Laugwitz KL, Kastrati A, ISAR-REACT 5 Trial Investigators (2019) Ticagrelor or Prasugrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med 381(1524):1534

Jneid H, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, Palacios IF, Kilic T, Moukarbel GV, Maree AO, LaBresh KA, Liang L, Newby LK, Fletcher G, Wexler L, Peterson E, Get With the Guidelines Steering C, Investigators (2008) Impact of time of presentation on the care and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 117:2502–2509

Kim SS, Jeong MH, Rhew SH, Jeong WY, Ahn YK, Cho JG, Kim YJ, Cho MC, Kim CJ, other Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry (2014) Impact of patients’ arrival time on the care and in-hospital mortality in patients with non-ST myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 113:262–269

Tofler GH, Brezinski D, Schafer AI, Czeisler CA, Rutherford JD, Willich SN, Gleason RE, Williams GH, Muller JE (1987) Concurrent morning increase in platelet aggregability and the risk of myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med 316:1514–1518

Freynhofer MK, Hein-Rothweiler R, Haller PM, Aradi D, Dezsi DA, Gross L, Orban M, Trenk D, Geisler T, Huczek Z, Toth-Gayor GG, Massberg S, Huber K, Sibbing D (2019) Diurnal variability of on-treatment platelet reactivity in clopidogrel versus prasugrel treated acute coronary syndrome patients: a pre-specified TROPICAL-ACS sub-study. Thromb Haemost 119:660–667

Scheer FA, Michelson AD, Frelinger AL 3rd, Evoniuk H, Kelly EE, McCarthy M, Doamekpor LA, Barnard MR, Shea SA (2011) The human endogenous circadian system causes greatest platelet activation during the biological morning independent of behaviors. PLoS ONE 6:e24549

Fournier S, Guenat F, Fournier A, Alberio L, Bonny O, Bertaggia Calderara D, Bardy D, Lauriers N, Harbaoui B, Monney P, Pascale P, Eeckhout E, Muller O (2018) Circadian variation of ticagrelor-induced platelet inhibition in healthy adulty. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 4:166–171

Menichelli M, Neumann FJ, Ndrepepa G, Mayer K, Wohrle J, Bernlochner I, Richardt G, Witzenbichler B, Sibbing D, Gewalt S, Angiolillo DJ, Lahu S, Hamm CW, Hapfelmeier A, Trenk D, Laugwitz KL, Schunkert H, Schupke S, Kastrati A (2020) Age- and weight-adapted dose of prasugrel versus standard dose of ticagrelor in patients with acute coronary syndromes : results from a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 173:436–444

Gonzalez MA, Ben-Dor I, Wakabayashi K, Maluenda G, Gaglia MA Jr, Hanna NN, Delhaye C, Collins SD, Syed AI, Mitulescu LP, Torguson R, Suddath WO, Lindsay J, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Waksman R (2010) Does on- versus off-hours presentation impact in-hospital outcomes of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients transferred to a tertiary care center? Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 76:484–490

Sorita A, Lennon RJ, Haydour Q, Ahmed A, Bell MR, Rihal CS, Gersh BJ, Holmen JL, Shah ND, Murad MH, Ting HH (2015) Off-hour admission and outcomes for patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. Am Heart J 169:62–68

Shavelle DM, Chen AY, Matthews RV, Roe MT, de Lemos JA, Jollis J, Thomas JL, French WJ, Investigators ACTION-GWTG (2014) Predictors of reperfusion delay in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction self-transported to the hospital (from the American heart association’s mission: lifeline program). Am J Cardiol 113:798–802

Shavelle DM, Zheng L, Ottochian M, Wagman B, Testa N, Hall S, Koenig W, Chan LS, Matthews RV (2013) Time of day variation in door-to-balloon time for STEMI patients in Los Angeles County: does time of day make a difference? Acute Card Care 15:52–57

Afolabi BA, Novaro GM, Pinski SL, Fromkin KR, Bush HS (2007) Use of the prehospital ECG improves door-to-balloon times in ST segment elevation myocardial infarction irrespective of time of day or day of week. Emerg Med J 24:588–591

Becker D, Soos P, Berta B, Nagy A, Fulop G, Szabo G, Barczi G, Belicza E, Martai I, Merkely B (2009) Significance of off-hours in centralized primary percutaneous coronary intervention network. Croat Med J 50:476–482

Breuckmann F, Hochadel M, Voigtlander T, Haude M, Schmitt C, Munzel T, Giannitsis E, Mudra H, Heusch G, Schumacher B, Barth S, Schuler G, Hailer B, Walther D, Senges J (2017) On versus off-hour care of patients with acute coronary syndrome and persistent ST-segment elevation in certified German chest pain units. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 6:3–9

Li M, Li S, Du X, Wu T, Li X, Ma C, Huo Y, Hu D, Gao R, Wu Y (2017) Factors attributed to the higher in-hospital mortality of ST elevation myocardial infarction patients admitted during off-hour in comparison with those during regular hour. PLoS ONE 12:e0175485

Breuckmann F, Remberg F, Bose D, Waltenberger J, Fischer D, Rassaf T (2016) On- versus off-hour care for patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in Germany : Exemplary results within the chest pain unit concept. Herz 41:725–731

Velibey Y, Tanik O, Oz A, Guvenc TS, Kalenderoglu K, Gumusdag A, Guzelburc O, Tekkesin AI, Uzun AO, Alper AT, Eren M (2017) Off-hour primary percutaneous coronary angioplasty does not affect contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with st-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Angiology 68:807–815

Casella G, Ottani F, Ortolani P, Guastaroba P, Santarelli A, Balducelli M, Menozzi A, Magnavacchi P, Sangiorgi GM, Manari A, De Palma R, Marzocchi A (2011) Off-hour primary percutaneous coronary angioplasty does not affect outcome of patients with ST-Segment elevation acute myocardial infarction treated within a regional network for reperfusion: The REAL (Registro Regionale Angioplastiche dell’Emilia-Romagna) registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 4:270–278

Schilling U, Dingemanse J, Ufer M (2020) Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Approved and Investigational P2Y12 Receptor Antagonists. Clin Pharmacokinet 59:545–566

Sibbing D, Aradi D, Alexopoulos D, Ten Berg J, Bhatt DL, Bonello L, Collet JP, Cuisset T, Franchi F, Gross L, Gurbel P, Jeong YH, Mehran R, Moliterno DJ, Neumann FJ, Pereira NL, Price MJ, Sabatine MS, So DYF, Stone GW, Storey RF, Tantry U, Trenk D, Valgimigli M, Waksman R, Angiolillo DJ (2019) Updated expert consensus statement on platelet function and genetic testing for guiding P2Y12 receptor inhibitor treatment in percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 12:1521–1537

Cassese S, Kastrati A (2020) Long-term ticagrelor versus prasugrel pharmacodynamics in patients with st-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc 9:e015726

Farrell B, French Merkley V, Ingar N (2013) Reducing pill burden and helping with medication awareness to improve adherence. Can Pharm J (Ott) 146:262–269

Montalescot G, Bolognese L, Dudek D, Goldstein P, Hamm C, Tanguay JF, ten Berg JM, Miller DL, Costigan TM, Goedicke J, Silvain J, Angioli P, Legutko J, Niethammer M, Motovska Z, Jakubowski JA, Cayla G, Visconti LO, Vicaut E, Widimsky P, ACCOAST Investigators (2013) Pretreatment with prasugrel in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 369:999–1010

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Supported by a grant (FKZ 81X1600501) from the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and the Deutsches Herzzentrum München, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report the following conflicts of interest: Dr. Bernlochner has received lecture fees from Sysmex Europe GmbH; Dr. Hochholzer reports personal fees from Bayer Vital, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Novartis, AstraZeneca, The Medicines Company; Dr. Sibbing has received personal fees from Daichi Sankyo, Sanofi and Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Pfizer and Servier; Dr. Angiolillo reports grants and personal fees from Amgen, Aralez, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Biosensors, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chiesi, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merc, Sanofi, CeloNova, personal fees from Haemonetics, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Pfizer, The Medicines company, St Jude Medical, grants from CSL Behring, Eisai, Gilead, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Matsutani Chemical Industry Co., Novartis, Osprey Medical, Renal Guard Solutions, Scott R. MacKenzie Foundation; Dr. Hemetsberger received speaker’s honoraria from Boston Scientific; Dr. Kufner reports personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Astra-Zeneca, and Translumina; Dr. Sager reports grants from European Research Council, Else-Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung, Deutsche Herzstiftung, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; Dr. Neumann has received personal fees from Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Novartis, and Ferrer; has received grants and personal fees from Pfizer, Biotronik, Edwards Lifesciences, Bayer Healthcare, and Boston Scientific; and has received grants from Medtronic and GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work; Dr. Schunkert has received personal fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Amgen, Bayer Vital GmbH, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Novartis, Servier, Brahms, Bristol Myers Squibb, Medtronic, Sanofi, Synlab; and has received grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca; Dr. Schüpke has received the Else Kröner-Memorial grant from the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung, financial support from the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK) and consulting fees from Bayer Vital GmbH and lecture fees from Daiichi Sankyo and Biopas Laboratories; Dr. Akin has received lecture fees from Boston Scientific, Boehringer, Daiichi Sankyo, Gore. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Behnes, M., Lahu, S., Ndrepepa, G. et al. Ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndrome with off-hour versus on-hour presentation: a subgroup analysis of the ISAR-REACT 5 trial. Clin Res Cardiol 112, 518–528 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-022-02040-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-022-02040-z