Abstract

Introduction and Hypothesis

The goal of this study was to determine whether dietary fat/fiber intake was associated with fecal incontinence (FI) severity.

Methods

Planned supplemental analysis of a randomized clinical trial evaluating the impact of 12-week treatment with percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus sham in reducing FI severity in women. All subjects completed a food screener questionnaire at baseline. FI severity was measured using the seven-item validated St. Mark’s (Vaizey) FI severity scale. Participants also completed a 7-day bowel diary capturing the number of FI-free days, FI events, and bowel movements per week. Spearman’s correlations were calculated between dietary, St. Mark’s score, and bowel diary measures.

Results

One hundred and eighty-six women were included in this analysis. Mean calories from fats were 32% (interquartile range [IQR] 30–35%). Mean dietary fiber intake was 13.9 ± 4.3 g. The percentage of calories from fats was at the higher end of recommended values, whereas fiber intake was lower than recommended for adult women (recommended values: calories from fat 20–35% and 22–28 g of fiber/day). There was no correlation between St. Mark’s score and fat intake (r = 0.11, p = 0.14) or dietary fiber intake (r = −0.01, p = 0.90). There was a weak negative correlation between the number of FI-free days and total fat intake (r = −0.20, p = 0.008). Other correlations between dietary fat/fiber intake and bowel diary measures were negligible or nonsignificant.

Conclusion

Overall, in women with moderate to severe FI, there was no association between FI severity and dietary fat/fiber intake. Weak associations between FI frequency and fat intake may suggest a role for dietary assessment in the evaluation of women with FI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fecal incontinence (FI), also known as accidental bowel leakage (ABL), is a debilitating condition that affects 9–19% of community dwelling women [1]. First-line management for FI includes conservative management techniques such as dietary modifications. Existing studies show that women with ABL are very interested in dietary modifications [2,3,4] and seek out advice on how to manage their diet to prevent FI. Unfortunately, the diet recommendations currently available for women are empirical, with limited supporting evidence [5].

Relatively few studies have investigated the role of diet in women with ABL. The few studies that exist suggest that compared with healthy controls, low dietary fiber intake may be associated with developing FI [6,7,8]; however, there are no data assessing the association of FI severity with fiber intake in women with FI. Similarly, there are scant data examining the role of dietary fat in FI severity despite the results of qualitative studies that reveal that women with FI commonly modify their fat intake to control their symptoms [2, 3]. This gap in knowledge likely contributes to patients’ reports of receiving inadequate therapeutic advice from their physicians regarding dietary changes to improve FI symptoms [4].

The goal of this study was to determine whether specific components of dietary intake are associated with FI severity. We hypothesize that dietary fiber and fat intake might be associated with FI severity.

Materials and Methods

This was a planned supplemental analysis of the previously published NeurOmodulatTion for Accidental Bowel Leakage (NOTABLe) trial, a randomized clinical trial evaluating the impact of 12-week treatment with percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) versus sham in reducing FI severity in women [9]. The NOTABLe trial population consisted of women aged ≥ 18 with moderate to severe ABL for ≥ 3 months and inadequate symptom control from supervised pelvic muscle training and constipating medications. Women with extremes of stool type (uncontrolled diarrhea or severe constipation), those with anatomical compromise to the anus or rectum, and those with known contraindications for PTNS were excluded [9].

The primary study was conducted at 9 US clinical sites of the National Institutes of Health Pelvic Floor Disorders Network with the approval of a Data and Safety Monitoring Board and the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board (NCT 03278613). All clinical trial participants provided written informed consent. The trial included a 4-week run-in phase prior to randomization to 12 weekly sessions of PTNS versus sham stimulation. Dietary intake data and baseline FI symptom severity were collected prior to the run-in phase. Participants also completed a 7-day bowel diary during week 1 of the run-in phase.

Dietary data were collected using a food screener questionnaire. The Food Screener is a validated one-page self-administered tool with two sections: a 17-item Meat/Snacks section designed to capture dietary fats and a ten-item Fruit/Vegetable section to capture fruit, vegetable, and fiber intake. The screener also captures liquid intake [10]. The instrument generates point estimates of total and saturated fat (g), percentage of calories from fat, daily fruit and vegetable servings, and fiber (g). The Food Screener has been validated against the 1995 Block 100-item Food Frequency Questionnaire and has been used in clinical and research settings to determine usual dietary intake [10]. A single question (dichotomous, yes/no) was added to the Food Screener to assess fiber supplement use. FI severity was measured using the seven-item validated St. Mark’s (Vaizey) FI severity scale. The scale assesses the type and frequency of anal incontinence, alteration in lifestyle from incontinence including the use of pads or plugs, the need to change underwear, the use of antidiarrheal medication, and the ability to defer defecation for 15 min. Total scores range from 0 to 24 with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity [11]. The 7-day bowel diary completed during week 1 of the run-in phase was reviewed to capture pertinent measures, including the number of FI-free days, the number of FI episodes, the number of urge-associated FI episodes, and the number of bowel movements per week.

Descriptive statistics were presented as proportions for categorical variables or as means (standard deviations) or medians (interquartile ranges) for continuous variables, as appropriate.

Spearman’s correlations were calculated between dietary intake with St. Mark’s score and with bowel diary measures. Given that the aim of the study was to assess the association between dietary intake and FI severity, the entire group was analyzed as a single cohort and the analyses were not stratified by treatment group (PTNS versus sham). Observed significant correlations were interpreted as follows: < 0.3 was considered low, between 0.3 and 0.5 was considered moderate, and ≥ 0.5 was considered high [12]. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

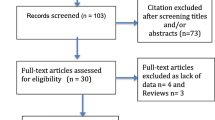

Enrollment for the NOTABLe trial occurred between 9 February 2018 and 24 September 2019. One hundred and ninety-nine women entered the run-in. For this analysis, the 186 women who completed the run-in phase and had complete diary data (defined as a minimum of 3 consecutive days during week 1 of the run-in phase) as well as dietary data and FI severity data available were included. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the women included in this analysis are presented in Table 1. Mean age and body mass index (BMI) were 63.8 ± 11.5 years and 29.4 ± 6.6 kg/m2 respectively. The mean baseline St. Mark’s score was 17.8 ± 2.6 and mean baseline FI episodes per week was 7.9 ± 7.8 indicating moderate to severe FI. Fiber supplementation was reported by 75 out of 180 (41.7%) of participants.

Dietary intake data are listed in Table 2. Mean total and saturated fat intake was 86.8 ± 20.7 g and 21.6 ± 7.6 g respectively and the median percentage of calorie consumption from fats was 32% [IQR 30–35%]. Mean fruit and vegetable servings were 3.3 ± 1.6 and mean fiber intake was 13.9 ± 4.3 g. Dietary intake reported by women with FI was higher in percentage of calories from fat and lower in fiber than recommended daily intakes (recommended values: calories from fat 20–35%; five fruit and vegetable servings/day; and 22–28 g of fiber/day).

There were no significant correlations between St. Mark’s score and fat intake (r = 0.11, p = 0.14), fruit/vegetable servings (r = 0.06, p = 0.45), or dietary fiber intake (r = −0.01, p = 0.90; Table 3). There was a weak negative correlation between the number of FI-free days and total fat intake (r = −0.20, p = 0.008) and fruit/vegetable servings (−0.21, p = 0.006; Table 4). Other correlations between dietary intake and bowel diary measures were negligible or nonsignificant (data not shown).

Discussion

Dietary advice is typically part of the first line of treatment for women with FI; however, data on the contribution of diet intake and modifications on FI symptoms are lacking. In this ancillary analysis of a large multicenter randomized trial, we sought to assess the relationship between dietary intake and bowel symptoms in women with FI. Although an association between FI severity and dietary fat/fiber intake was not found, weak associations were noted between greater FI frequency and increasing fat intake. The findings of this study add to the limited data on dietary intake in women with FI and may suggest a role for dietary assessment in the evaluation of women with FI.

The associations found between bowel symptoms and fat intake were weak and of unclear clinical significance; however, they are not surprising. In qualitative studies that examine self-care practices of women with FI, women report that they commonly modify their fat intake to control FI symptoms [3]. Mechanistically, a high fat diet could cause FI by causing stools to be too hard or too liquid, both of which are independent risk factors for FI in large epidemiological studies [13,14,15,16]. Fat intake has also been shown to decrease gastrointestinal motility and negatively affect the function of the neurons in the enteric nervous system [17, 18]. Although these studies suggest that dietary fat might be able to alter stool consistency and/or gastrointestinal motility and potentially contribute to FI, existing studies investigating the diet of women with FI are limited. Even though the current findings add to the available data on the relationship between dietary fat and FI, additional studies are needed to examine this relationship more robustly.

There was no association between dietary fiber intake and FI severity within our cohort. Prior studies have suggested that there might be an inverse relationship between dietary fiber intake and development of FI [6, 8]; however, others have not reported an association between intake of food with varying amounts of fiber and FI severity. It is possible that given that the dietary fiber intake amongst our cohort was very low with a narrow distribution, there was a limited ability to detect a correlation. Our cohort, though, is similar to other reported cohorts of women with FI with lower-than-average fiber consumption. Prior studies reporting on diet intake of women with FI found a mean daily dietary fiber intake of 13–15 g, which is similar to our cohort [19, 20]. Thus, prospective intervention studies that assess the impact of varying intakes in dietary fiber are likely needed to fully assess the relationship between dietary fiber and FI severity.

Documentation of usual dietary intake may be helpful in the workup and management of women with FI, especially if noted to be outside the recommended ranges for proportion of fat, fat type, and fiber intake. Additionally, assessing dietary intake enables the identification of potential triggers and provides diet modification opportunities that may improve symptoms. Currently, dietary advice provided for women with FI is usually empirical, i.e., increase dietary fiber and decrease fat. As Bliss et al. noted, even in the absence of change in overall nutrition profile, managing FI may require increased or decreased consumption of specific individual foods [19]. Assessing current usual diet intake may provide an opportunity to personalize the dietary advice provided and improve the current conservative management strategies for treating FI. In this study, a simple food questionnaire was used to ascertain usual dietary intake. Other methods such as food diaries and 24-h dietary recalls have also been employed to measure dietary intake, although they require more effort [21].

Strengths of this study include use of a large, well-characterized, multicenter cohort of women with moderate to severe FI from a randomized controlled trial. A validated food screener and validated FI severity questionnaires that have been utilized in both clinical and research settings to document diet intake and bowel symptoms were used. There are also several limitations. The screener allows point estimates of food categories such as meat/snacks and fruits/vegetables, but only assesses a limited profile of dietary intake and does not provide granular details about individual foods that would allow an assessment of potential triggers. Although St. Mark’s scale has been extensively validated and is widely accepted as a measure of FI severity, there are limitations in that it may not adequately reflect the severity of FI in some patients, such as those with passive FI, and may not capture the total patient perspective on their symptoms [22]. Women completed the food screener during the run-in phase of the randomized controlled trial, which may affect their report of dietary intake. We only included a single nonspecific question about the use of fiber supplementation and thus we are unable to comment on the varied types of fiber supplements and the different effects they may have on bowel function. We did not collect data on history of cholecystectomy or colon surgery, which can impact FI symptoms and dietary absorption. Finally, there are limitations inherent to the primary study, including that this was a cohort of women seeking care for FI at urogynecology clinics and thus these findings may not be generalizable to a different population, and comparison with a control group without FI is beyond the scope of this paper [9].

In conclusion, this study adds to the current literature on dietary intake in women with FI. A weak and unclear clinically significant association was noted between FI and fat intake that may suggest a role for dietary assessment in the evaluation and management of women with FI.

Data Availability

The data for the trial is publicly available through the NICHD Data and Specimen Hub.

References

Brown HW, Dyer KY, Rogers RG. Management of fecal incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136(4):811–22.

Andy UU, Ejike N, Khanijow KD, et al. Diet modifications in older women with fecal incontinence: a qualitative study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26(4):239–43.

Bliss DZ, Fischer LR, Savik K. Managing fecal incontinence: self-care practices of older adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 2005;31(7):35–44.

Hansen JL, Bliss DZ, Peden-McAlpine C. Diet strategies used by women to manage fecal incontinence. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2006;33:52–62.

Bowel Control Problems (Fecal Incontinence). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020 (https://www.niddk.nih.gov/healthinformation/digestive-diseases/bowel-control-problems-fecalincontinence). Accessed 21 Mar 2021.

Markland AD, Richter HE, Burgio KL, Bragg C, Hernandez AL, Subak LL. Fecal incontinence in obese women with urinary incontinence: prevalence and role of dietary fiber intake. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(5):566.e1–6.

Croswell E, Bliss DZ, Savik K. Diet and eating pattern modifications used by community-living adults to manage their fecal incontinence. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2010;37(6):677–82.

Staller K, Song M, Grodstein F, et al. Increased long-term dietary fiber intake is associated with a decreased risk of fecal incontinence in older women. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(3):661–667.e1.

Zyczynski HM, Richter HE, Sung VW, et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation vs sham stimulation for fecal incontinence in women: neuromodulation for accidental bowel leakage randomized clinical trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:654–67.

Block G, Gillespie C, Rosenbaum EH, Jenson C. A rapid food screener to assess fat and fruit and vegetable intake. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(4):284–8.

Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, Kamm MA. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut. 1999;44:77–80.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah: Erlbaum; 1988.

Robinson BL, Matthews CA, Whitehead WE. Obstetric sphincter injury interacts with diarrhea and urgency to increase the risk of fecal incontinence in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(1):40–5.

Whitehead WE, Borrud L, Goode PS, et al. Fecal incontinence in US adults: epidemiology and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(2):512–7.e1–2.

Rey E, Choung RS, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ. Onset and risk factors for fecal incontinence in a US community. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(2):412–9.

Bharucha AE, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, Melton LJ 3rd. Bowel disturbances are the most important risk factors for late onset fecal incontinence: a population-based case-control study in women. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(5):1559–66.

Mushref MA, Srinivasan S. Effect of high fat-diet and obesity on gastrointestinal motility. Ann Transl Med. 2013;1(2):14.

Nezami BG, Mwangi SM, Lee JE, et al. MicroRNA 375 mediates palmitate-induced enteric neuronal damage and high-fat diet-induced delayed intestinal transit in mice. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(2):473–83.e3.

Bliss DZ, McLaughlin J, Jung HJ, Lowry A, Savik K, Jensen L. Comparison of the nutritional composition of diets of persons with fecal incontinence and that of age- and gender-matched controls. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2000;27(2):90–1, 93–7.

Nakano K, Takahashi T, Tsunoda A, Matsui H, Shimizu Y. Dietary trends in patients with fecal incontinence compared with the National Health and Nutrition Survey. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2019;3(2):69–72.

Bailey RL. Overview of dietary assessment methods for measuring intakes of foods, beverages, and dietary supplements in research studies. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2021;70:91–6.

Maeda Y, Parés D, Norton C, Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA. Does the St. Mark’s incontinence score reflect patients’ perceptions? A review of 390 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(4):436–42.

Acknowledgements

Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI, USA: Cassandra Carberry, B. Star Hampton, Nicole Korbly, Ann Schantz Meers, Vivian Sung, Kyle Wohlrab, Sarashwathy Veera, Elizabeth-Ann Viscione; University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center: Sunil Balgobin, Juanita Bonilla, Agnes Burris, Christy Hegan, David Rahn, Joseph Schaffer, Clifford Wai; Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA: Cindy L. Amundsen, Matthew D. Barber, Yasmeen Bruton, Nortorious Coleman-Taylor, Cassandra Shaw, Amie Kawasaki, Tracy O’Dowd, Nazema Y. Siddiqui, Anthony Visco, Alison C. Weidner; Kaiser Permanente, San Diego: Kimberly Ferrante, Gouri Diwadkar, Christina Doan, Rebekah Dozier, Lynn Hall, Shawn Menefee, Gisselle Zazueta-Damian; RTI International: Andrew Burd, Kate Burdekin, Kendra Glass, Brenda Hair, Michael Ham, Pooja Iyer, James Pickett, Amanda Shaffer, Taylor Swankie, Yan Chen Tang, Dennis Wallace; University of Alabama at Birmingham, Alabama: Danielle Hays, Kathy Carter, David Ellington, Ryanne Johnson, Alayne Markland, Jeannine McCormick, Isuzu Meyer, Robin Willingham; UC San Diego Health, San Diego, CA, USA: Marianna Alperin, Laura Aughinbaugh, Linda Brubaker, Kyle Herrala, Emily Lukacz, Charles Nager, Dulce Rodriguez-Ponciano, Erika Ruppert; University of Pennsylvania: Lily Arya, Yelizaveta Borodyanskaya, Lorraine Flick, Heidi Harvie, Zandra Kennedy; Magee-Women’s Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Mary Ackenbom, Lindsey Baranski, Michael Bonidie, Megan Bradley, Pamela Fairchild, Judy Gruss, Beth Klump, Lauren Kunkle, Jacqueline Noel, Pamela Moalli, Halina Zyczynski.

Funding

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grants HD069006, HD069031, HD041261, HD069010, HD069013, HD054214, HD041267, HD054241 and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

U.U.A.: project development, data collection, manuscript writing; J.I.-P.: project development, data analysis, manuscript writing; B.C.: project development, data analysis, manuscript writing; H.E.R.: project development, data collection, manuscript writing; K.Y.D.: project development, data collection, manuscript writing; M.F.-R.: project development, data collection, manuscript writing; G.S.N.: project development, data collection, manuscript writing; D.M.: project development, data collection, manuscript writing; M.O.S.: project development, data collection, manuscript writing; D.M.: project development, manuscript writing; M.G.G.: project development, data analysis, manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

H. Richter: research grants from PCORI (Brown University, Dartmouth University), NIH/NIA (UT Southwestern), NICHD (Univ of Minnesota), NIDDK (Mayo), NICHD (RTI), Renovia, Reia, Allergan; DSMB member: BlueWind Medical, Hologic LLC; Royalties: UpToDate; BOD: WorldWide Fistula Fund, SOLACE; Editor and Editorial Board: International Urogynecology Journal; Editor: Current Geriatric Reports; Consultant: Neomedic, Coloplast, Palette Life Sciences, COSM, Laborie. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Catherine Matthews

Editor in Chief: Maria A. Bortolini

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Andy, U.U., Iriondo-Perez, J., Carper, B. et al. Dietary Intake and Symptom Severity in Women with Fecal Incontinence. Int Urogynecol J 35, 1061–1067 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-024-05776-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-024-05776-6