Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Seeking health information online has drastically increased. As primary bladder pain syndrome (PBPS) is a condition that has no definitive diagnosis and treatment protocol, patients may seek answers on YouTube. We aimed to evaluate the role of the videos related to PBPS hosted on YouTube.

Methods

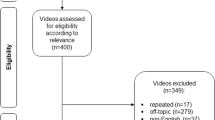

We searched PBPS-related YouTube videos using the keywords "primary bladder pain syndrome," "painful bladder syndrome," and "interstitial cystitis." The videos not in English, not relevant, or that do not contain audio were excluded. The characteristics of the videos were collected. The videos were primarily classified as reliable and nonreliable based on the scientifically proven accurate information they contained. The overall quality of the videos was assessed by DISCERN and Global Quality Score (GQS). Intraclass correlation was used to calculate the level of agreement between the two investigators on DISCERN and GQS values.

Results

Of the 300 videos, 175 were excluded. A total of 62 (49.6%) videos were considered reliable and 63 (50.4%) nonreliable. Only video lengths differed statistically in favor of reliable videos (p < 0.001). DISCERN and GQS values were higher in the reliable videos group (p < 0.001 for each). The number of views, likes, dislikes, and comments were slightly lower in the videos uploaded from universities/nonprofit physicians or professional organizations than other groups.

Conclusions

Although about half of the videos are reliable, most are long and are medical lectures, from which it is difficult for nonhealth professionals and patients to obtain information. On the other hand, most of the videos that patients can follow more easily consist of nonreliable video groups that lack accuracy, detail, and factual content. Therefore, the relevant associations with experts should prepare concise videos containing correct and up-to-date information.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Doggweiler R, Whitmore KE, Meijlink JM, et al. A standard for terminology in chronic pelvic pain syndromes: a report from the chronic pelvic pain working group of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36:984–1008. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23072.

Ghai V, Subramanian V, Jan H, et al. Evaluation of clinical practice guidelines (CPG) on the management of female chronic pelvic pain (CPP) using the AGREE II instrument. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32:2899–912. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-04848-1.

Roberts RO, Bergstralh EJ, Bass SE, et al. Incidence of physician-diagnosed interstitial cystitis in Olmsted County: a community-based study. J Reprod Med. 2004;49:181–5. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04060.x.

Burkman RT. Chronic pelvic pain of bladder origin: epidemiology, pathogenesis and quality of life. J Reprod Med. 2004;49:225–9.

Temml C, Wehrberger C, Riedl C, et al. Prevalence and correlates for interstitial cystitis symptoms in women participating in a health screening project. Eur Urol 2007;51:803–8; discussion 809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2006.08.028

Lee M-H, Chang K-M, Tsai W-C. Morbidity rate and medical utilization in interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1045–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3574-x.

Ali A, Ali NS, Malik MB, et al. An overview of the pathology and emerging treatment approaches for interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Cureus. 2018;10:e3321. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.3321.

Giusto LL, Zahner PM, Shoskes DA. An evaluation of the pharmacotherapy for interstitial cystitis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19:1097–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2018.1491968.

Amante DJ, Hogan TP, Pagoto SL, et al. Access to care and use of the Internet to search for health information: results from the US National Health Interview Survey. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e106. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4126.

Gul M, Diri MA. YouTube as a source of information about premature ejaculation treatment. J Sex Med. 2019;16:1734–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.08.008.

LaValley SA, Kiviniemi MT, Gage-Bouchard EA. Where people look for online health information. Health Info Libr J. 2017;34:146–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12143.

Alexa. The top 500 sites on the web. Available at: https://www.alexa.com/topsites. Accessed 03 Nov 2021.

Sandvine. The Global Internet Phenomena Report, October 2020. Available at: https://www.sandvine.com/download-report-mobile-internet-phenomena-report-2020-sandvine. Accessed 03 Nov 2021.

Ho M, Stothers L, Lazare D, et al. Evaluation of educational content of YouTube videos relating to neurogenic bladder and intermittent catheterization. Can Urol Assoc J 2015;9:320–54. https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.2955

Salman MY, Bayar G. Evaluation of quality and reliability of YouTube videos on female urinary incontinence. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:102200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogoh.2021.102200.

Larouche M, Geoffrion R, Lazare D, et al. Mid-urethral slings on YouTube: quality information on the internet? Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27:903–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-015-2908-1.

Google trend search. Bladder pain syndrome, Painful bladder syndrome, Interstitial cystitis. Available at: https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=Primary. Accessed 03 Nov 2021.

EAU Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain. Edition presented at the EAU Annual Congress Milan 2021. EAU Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain. Engeler D (Chair), Baranowski AP, Berghmans B, et al. EAU Guidelines Office, Arnhem, The Netherlands. http://uroweb.org/guidelines/compilations-of-all-guidelines/. Accessed 03 Nov 2021.

Singh AG, Singh S, Singh PP. YouTube for information on rheumatoid arthritis—a wakeup call? J Rheumatol. 2012;39:899–903. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.111114.

Esen E, Aslan M, Sonbahar BÇ, Kerimoğlu RS. YouTube English videos as a source of information on breast self-examination. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;173:629–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-5044-z.

Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:105–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.53.2.105.

Bernard A, Langille M, Hughes S, et al. A systematic review of patient inflammatory bowel disease information resources on the World Wide Web. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2070–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01325.x.

Sood A, Sarangi S, Pandey A, Murugiah K. YouTube as a source of information on kidney stone disease. Urology. 2011;77:558–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2010.07.536.

Hanno PM, Erickson D, Moldwin R, Faraday MM. Diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: AUA guideline amendment. J Urol. 2015;193:1545–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.086.

Garg N, Venkatraman A, Pandey A, Kumar N. YouTube as a source of information on dialysis: a content analysis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2015;20:315–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/nep.12397.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.F. Batur: project development, video evaluation, data collection, analysis of data, manuscript writing, revision; E. Altintas: video evaluation, data collection; M. Gül: project development, manuscript editing, revision for important intellectual content, language editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not obtained for the study as access to the videos is legally available to the public.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Batur, A.F., Altintas, E. & Gül, M. Evaluation of YouTube videos on primary bladder pain syndrome. Int Urogynecol J 33, 1251–1258 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-022-05107-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-022-05107-7