Abstract

Since the expansion of the universe was first established by Edwin Hubble and Georges Lemaître about a century ago, the Hubble constant \(H_0\) which measures its rate has been of great interest to astronomers. Besides being interesting in its own right, few properties of the universe can be deduced without it. In the last decade, a significant gap has emerged between different methods of measuring it, some anchored in the nearby universe, others at cosmological distances. The SH0ES team has found \(H_0 = 73.2 \pm 1.3 \; \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\) locally, whereas the value found for the early universe by the Planck Collaboration is \(H_0 = 67.4 \pm 0.5 \; \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\) from measurements of the cosmic microwave background. Is this gap a sign that the well-established \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\) cosmological model is somehow incomplete? Or are there unknown systematics? And more practically, how should humble astronomers pick between competing claims if they need to assume a value for a certain purpose? In this article, we review results and what changes to the cosmological model could be needed to accommodate them all. For astronomers in a hurry, we provide a buyer’s guide to the results, and make recommendations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

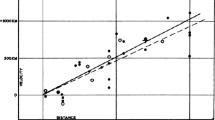

In 1917, Einstein was the first to combine the assumptions of homogeneity and isotropy with his new theory of general relativity, and produce a solution for the universe as a whole (Einstein 1917). Einstein imposed his belief in a static universe, and famously introduced the cosmological constant \(\varLambda \), to make his equations compatible with this assumption. Friedmann (1922) derived a solution for an expanding (or contracting) universe, but his work remained largely unknown until after his death. Establishing expansion as an observational fact was very challenging with the technology of the day. George Lemaître published the first estimate of the expansion rate in Lemaître (1927). Two years later, Edwin HubbleFootnote 1 combined his observations of stellar magnitudes using the Mount Wilson telescope with Shapley’s, Humanson’s and Slipher’s redshifts z to a similar result (Hubble 1929) (Fig. 1). Hubble’s constant, as it later became known, is then the constant of proportionality between recession speed v and distance d:

Hubble’s original diagram from Hubble (1929). Despite the typo on the labelling of the y-axis, which should read \(\hbox {kms}^{-1}\) and not \(\hbox {km}\), it is still easy to read off \(H_0 \simeq 500\; \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\). Hubble and Humanson were using the largest telescope in the world at the time. M31 is recognisable as the lowest black dot in the bottom left; Humanson had determined it is velocity as \(220 \;\hbox {kms}^{-1}\) towards the Milky Way (the modern value is \(110 \;\hbox {kms}^{-1}\))

Surprisingly perhaps, it was not until 1958 that the first recognisably modern value \(H_0 \simeq 75 \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\) was published (Sandage 1958). Sandage made several corrections to Hubble’s earlier results. First, he noted the population of Cepheid variable stars was not as homogeneous as first thought. This added both scatter and bias to distance estimates, compounded by the low numbers of Cepheids observed. Second, and more seriously, Hubble had mistaken (far brighter) HII regions as bright stars, and, therefore, his estimate of the distances to galaxies was too low.

Fast forward to today, and these historical developments seem to echo some present day debates. \(H_0\) is measured in a number of ways, which produce inconsistent values. In particular, in 2018, the Planck Collaboration used the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) temperature and polarization anisotropies and the \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\) cosmological model, to find \(H_0 = 67.4 \pm 0.5 \; \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\) (Planck Collaboration 2020) whereas in 2021 the SH0ES Collaboration (Riess et al. 2021) used Cepheids and supernovae to find \(H_0 = 73.2 \pm 1.3 \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\) (here, and for the rest of the review we quote 68% confidence limits). We show the main modern results in Fig. 2.

Why should this disagreement matter? First, it may be a sign that the standard cosmological model is incomplete and new physics is required. All \(H_0\) results place some reliance on a background cosmology (for example to obtain peculiar velocity adjustments from a model), but the sensitivity is large when comparing results projected over large distances. Second, other cosmological parameters such as matter densities, curvature and large scale structure are often degenerate with \(H_0\) in observational data; knowing \(H_0\) more accurately helps resolve their values too. Third, knowing \(H_0\) accurately improves astrophysics, as distances in the universe are \(\propto H_0^{-1}\). Its dimensionless cousin \(h = H_0 / 100 \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\) is ubiquitous in formulae.

We organise our review as follows. Section 1 defines \(H_0\) and distances; it may be skipped by a reader familiar with cosmological models. In Sect. 2, we show how \(H_0\) is calculated from observational data, and the type of problems that might generally arise. We also briefly discuss the use of Bayesian methods as a tool to discriminate between competing observations and models. In Sect. 3, we discuss ways in which \(H_0\) has been recently estimated. There is a rich literature on the subject, and it is difficult to cover all papers. Our approach is to cite for each topic a seminal paper, and the recent most significant developments. In Sect. 4, we discuss the possibility that measurements are correct, and it is our understanding of cosmology that is wrong. In Sect. 5 we conclude, and in the spirit of our guide for consumers, we provide our buyer’s advice and recommendations. We aim to be impartial, and the views expressed here are solely our own. Busy readers could review Sects. 2, 4 and 5, and dip into Sect. 3 if more detail is needed.

For the remainder of this review, we adopt \(c=1\) throughout the text.

Summary of recent \(H_0\) measurements. We have intentionally selected a limited number of results to show those that are as independent from each other as possible, in the sense that they use different photometric data, distance calibrators and so on. More comprehensive versions of this plot can be found for example in Di Valentino et al. (2021). Comments: (1) CCHP and Yuan et al. share a common distance to LMC as a calibrator. (2) TDCOSMO is a re-analysis of almost the same data as H0LiCOW, but with changes to the galactic potentials. (3) BOSS and DES share a prior constraint on baryon densities from BBN. (4) The results of Blakeslee et al. use new SBF observations, whereas Khetan et al. use archival SBF distances to calibrate SN Ia. The code use to generate this figure is publicly available at https://github.com/Pablo-Lemos/plot1d

1.1 Linking \(H_0\) to H(z)

Hubble’s “constant” (Eq. 1) is not fixed when we observe beyond our local cosmological neighbourhood; which is to say it is not fixed in time. Therefore, we write \(H_0 \equiv H(t_0)\), where \(t_0\) is the present day and in general \(H = H(t)\). The expansion has slowed down in the past, but the universe is now accelerating (since \(z \sim 0.6\)) and has been dark energy dominated since \(z \sim 0.3\). The change in H(t) may be written using the phenomenological deceleration parameter q(t) as

In our local universe q(t) is approximately constant, and hence some authors adopt \(q_0 \equiv q(t_0)\) as a constant (see for example Riess et al. 2016 or Freedman et al. 2019). As redshift is a monotonically decreasing function of time, we can write \(H = H(z)\) and approximate

As \(q_0 \simeq -0.55\), light travelling to us from more than \(100 \;\,\hbox {Mpc}\) away will have been emitted when the Hubble constant was more than 1% different to its current value. The purpose of phrasing cosmography in this way is to avoid explicit assumptions on the matter or energy content of the universe, and it is of course possible to use more general parametrisations to expand H(z). While this approximation is reasonable for \(z \ll 0.1\), if we wish to go further, or link phenomenological parameters to physical quantities, we need a cosmological model.

Cosmological models usually assume the universe is homogenous and isotropic on large scales, and has a space-time metric. Under those assumptions, the Friedmann–Robertson–Walker (FRW) metric is

where a(t) is a scale factor defining how physical distances evolve with cosmological time t, and \((r, \theta , \phi )\) are comoving polar coordinates centered on ourselves. k is a curvature parameter, which here has units of inverse area as we wish to set \(a(t_0) = 1\) (an alternative convention is to set \(k = 0, \pm 1\) but it is not in general possible to do both). Results from Planck (Planck Collaboration 2020) for the CMB in isolation show a preference for mildly closed universe where \(k>0\), and allowing k to vary from zero lowers the CMB derived \(H_0\) to \(63.6^{+2.1}_{-2.3} \; \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\). However, most other observational evidence points to a flat universe (for example galaxy survey data or gravitational lensing of the CMB—see for example Efstathiou and Gratton 2020). Our discussion would not be materially affected by including spatial curvature, and for this review we will assume a flat universe where \(k = 0\). We return to the point in Sect. 4.

The Hubble parameter is then defined as

where \({\dot{a}} \equiv da/dt\). The scale factor and redshift are related by

By \(z_{\mathrm{cos}}\), we mean the redshift that would be seen if both the observer and emitter were stationary in comoving coordinates, which we take to be the frame in which the CMB has no dipole. Peculiar velocity is then the velocity with respect to this frame. We know the solar peculiar velocity relative to the CMB from our observed dipole, but to estimate \(z_{\mathrm{cos}}\) from the observed redshift \(z_{\mathrm{obs}}\) we also need the peculiar velocity of the emitter. For example, a 10% error in a peculiar velocity of \(300 \;\hbox {kms}^{-1}\) of a galaxy lying at \(50 \;\,\hbox {Mpc}\) away would result in a 1% error in \(H_0\) were we to calculate it solely from that galaxy. For that reason, astronomers seek large numbers of objects distributed across the sky, deep into the “Hubble flow”, meaning their peculiar velocities are small compared to Hubble expansion and are assumed to average out. From here, we write \(z = z_{\mathrm{cos}}\) unless indicated otherwise.

The \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\) cosmological model is defined as

This can be generalised with an equation of state parameter \(p = w \rho \) for dark energy where p is pressure, and the above corresponds to the cosmological constant \(w = -1\). The fictitious curvature density is \(\varOmega _{k} = 1 - \varOmega _m - \varOmega _r - \varOmega _{\varLambda }\), and we have assumed spatial flatness \(\varOmega _{k} = 0\).

The present day density fractions for matter, radiation and dark energy \(\varOmega _{i,0} \equiv \varOmega _i (z=0)\) are defined in terms of the physical densities \(\rho _i\) as

It is straightforward to expand H(a(z)) as a Taylor series in z and obtain Eq. (3) to first order where

So, in a narrow sense, a cosmological model is a function to derive H(z) from \(H_0\) and \(\varOmega _i\) or vice versa (provided nothing converts energy from one type to another). This is how \(H_0\) is calculated from H(z) at \(z \sim 1100\) for the CMB. Hence, one way to reconcile the Hubble tension is to change the function \(H(z, \varOmega _i)\) by adding new energy components or novel interactions, and we return to this later.

1.2 Distances from angles and fluxes

Luminosity distance is defined to recover the standard inverse square law ratio between the bolometric luminosity L and flux F that would hold in a flat, static universe:

In a homogeneous and isotropic universe we find

where it is conventional to make the dependence on \(H_0\) explicit by setting \(H(z) \equiv H_0 E(z)\). Substituting in Eq. (7), for flat \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\) we have

Angular diameter distance is the ratio between the physical size l of a distant object, and the small angle \(\delta \theta \) it subtends on the sky:

The Etherington relation (Etherington 1933)

is a useful way to convert between the two.Footnote 2

To link \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\) to our local universe, we expand Eq. (7) to second order in z:

where the jerk parameter \(j_0\) is defined as

Eq. 15 is now a reasonable approximation to Eqs. (7) and (11) out to \(z \sim 0.6\).

Setting \(\varOmega _{r,0} \simeq 0\), we then obtain \(q_0 = \frac{1}{2}(\varOmega _{m,0} - 2 \varOmega _{\varLambda ,0})\) and \(j_0 = \varOmega _{m,0} +\varOmega _{\varLambda ,0} \simeq 1\).

Hubble’s law \(v= H\, d\) is implicit in Eq. (11). Expanding the integral as a Taylor series in z, we see that \(v = cz\) as used by Hubble and Lemaître (and re-introducing c here for clarity) is only valid as a low-z approximation.

1.3 The age of the universe

The age of the universe \(t_0\) is inversely proportional to \(H_0\), with dependence on other cosmological parameters. From the definition of \(H(t) = {\dot{a}}/a\) we can write

In the special case of a flat, radiation-free universe, where we set \(\varOmega _{m,0} + \varOmega _{\varLambda ,0} =1\), it can be written analytically as

For a flat universe with \(\varOmega _{m,0}= 0.3\) this gives \(H_0 t_0 \approx 0.96\). Historically (in the 1980s), it was believed that the universe was Einstein–de Sitter (\(\varOmega _{m,0}= 1.0\) and \(\varOmega _{\varLambda ,0} = 0.0\)), which yields the product \(H_0 t_0 = \frac{2}{3}\). Then, a low value of \(H_0 \approx 50 \; \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\) was required to ensure that the universe is older than the oldest globular clusters. The existence of \(\varLambda > 0 \) makes the universe naturally older. The Planck estimate is \(t_0 = 13.797 \pm 0.023\,\mathrm { Gyr}\) within \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\) (Table 2 for Planck alone, 68% CL; Planck Collaboration 2020). This value for the age of the universe is comfortably larger than the age of any known astronomical object.

2 Inference of \(H_0\)

2.1 Standard candles and the nearby distance ladder

A standard candle is any population of stars or events which

-

can be reliably identified

-

have the same characteristics wherever they are seen

-

have an established luminosity law specifying the absolute magnitude in terms of observable quantities.

Although the luminosity law is determined empirically by calibration (except in the case of gravitational waves—see Sect. 2.3), there is an advantage if there is also a solid understanding of the underlying physics of the standard candle as in that case the calibration can be cross-checked against a theoretically-derived one.

The nearby distance ladder starts with a choice of standard candle, and a calibration of the absolute magnitude M, for example using parallax distances and apparent magnitudes m. m is defined by

where \(F_{X}\) is the energy flux per unit area per second across the wavelength range of the band X, and \(F_{X,0}\) is the fixed reference flux for the magnitude system being used (for example the Vega system). M is the apparent magnitude the object would have if it were at a distance of 10 parsecs. Distance is conveniently quoted as the distance modulus

and then the luminosity distance (10) becomes

which can then be substituted into Eqs. (11), (15) or similar relations to obtain \(H_0\).

A given standard candle seen over a range of distances is termed a “rung”, and in turn used as calibrators for the next rung. For example, the SH0ES team (Riess et al. 2019) calibrate Classical Cepheids (CC) using parallaxes, a maser distance to NGC4258, and detached eclipsing binaries (DEBs) in the LMC as their first rung. Their next rung is Type Ia supernovae (SN Ia), calibrated using the 19 galaxies in which both Cepheids and SN Ia have been observed. We illustrate their construction in Fig. 3.

Our schematic illustration of the construction of distance ladders. Green circles represent the calibration of the distance ladder (either the base or overlap of each rung), and the bars are the rungs of the distance ladder. The size of dots or thickness of bars are in proportion to their contribution to the error budget of \(H_0\); in the case of the CMB and BBN we have opted for a thin line to show the dependence on \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\)

The quality of the standard candle depends on a number of considerations. Are there enough with good distances to accurately calibrate the absolute magnitude? Can we clearly identify them at large distances? Can they be observed out to a sufficient distance to reach the next rung? Are the objects observed at large distances of the same type as local ones used as calibrators? How to correct for extinction, reddening, metallicity effects and crowded starfields? Which band has the most reliable magnitudes? If data have been combined from different telescopes, have the right adjustments been made to convert photometry? How is magnitude to be defined for variable stars? Each rung depends on the previous one, and errors will propagate up the ladder.

A more subtle issue is that the conversion of observational data to \(H_0\) is non-linear. As the expectation \({\mathbb {E}}[d^n] \ne {\mathbb {E}}[d]^n\) in general, scatter in observational data will introduce systemic bias. Bias can also be introduced by sample selection unless care is taken as \({\mathbb {E}}[d_1< d < d_2] \ne {\mathbb {E}}[d]\): we average our selected sample but wish to know the expectation of the unselected one. Selection may be overt (for example by cutting outliers) or due to our telescope seeing only up to \(m < m_0\) (known as Malmquist bias; Malmquist 1922). Both of these can be (and usually are) corrected for, but require some assumptions and a careful analysis of the data and reduction pipeline.

2.2 Standard rulers and the inverse distance ladder

A standard ruler is a feature on the sky of a known physical size l, which enables us to calculate the angular diameter distance \(d_A\) defined in Eq. (13) from their angular size. Parallax is an obvious example, and also the size of orbits of masers and detached eclipsing binaries can be determined from their positions, light curves and spectroscopy. In the early universe, acoustic pressure waves in the primordial charged particle and radiation plasma set a physical size called the sound horizon \(r_s\), which is how far they travel from the initial seedsFootnote 3 that generate them. The universe was not that dense at that time, so Thomson scattering by charged particles was necessary to propagate the waves, and hence they are frozen-in by recombination. The sound horizon is then imprinted on the CMB as peaks in the power spectrum of temperature fluctuations, and in the later spatial distribution of galaxies (known as baryon acoustic oscillations, or BAO for short).Footnote 4 The sound horizon may be calculated in a cosmological model, and depends both on the expansion rate H(z) (the waves are carried along by expanding spacetime) and the matter-energy content of the early universe (determining the sound speed).

The inverse distance ladder, as its name suggests, works in the opposite direction to the nearby distance ladder but on the same principle. It can use the sound horizon for a starting \(d_A\), a background cosmology, and the Etherington relation (14) to calibrate the luminosity distances \(d_L\) of standard candles. For example, Lemos et al. (2019) calibrate BAO at \(z \simeq 1\) and SN Ia at \(z<1\) using the CMB sound horizon. They replace the standard \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\) formula for H(z) with a parametric form. H(z) is extrapolated to today to find \(H_0 = 68.42 \pm 0.88 \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\). Thus, it is shown that discrepancy between the CMB value of Planck Collaboration (2020) and Riess et al. (2019) is not caused by assuming the late-universe is \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\).

We can express the difference between early and late universe \(H_0\) in terms of ruler size or luminosity differences. Planck implies \(r_s = 147.27 \pm 0.31\) Mpc in \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\); it would need to be \(\simeq 10\) Mpc lower (Knox and Millea 2020) to bring consistency with Riess et al. (2019). Alternatively, Eqs. (21) and (11) show that Cepheids or SN Ia would need to be \(\simeq 0.2\) mag brighter than thought to bring consistency with Planck.

In summary, we see the two ways of constructing ladders, propagated toward each other by the “guard rails” of SN Ia, do not meet! Hence, the \(H_0\) tension is sometimes characterised as “early” versus “late”, from which follows the question “Is \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\) right?”. This may be premature: in fact, few late-universe results in isolation are fully inconsistent with early universe ones, as we discuss later.

2.3 No-ladder \(H_0\)

We have seen distance ladders require calibration, whether they are nearby or inverse. However, there are some self-calibrating observations from which \(H_0\) may be calculated directly.

One example is the CMB. The detailed shape of the power spectrum determines other parameters in \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\), and the value of \(H_0\) derived from it is best understood as just one part of the simultaneous inference of all cosmological parameters. A further example is maser emission systems, which occur in the nucleus of certain galaxies and are bright enough to be seen at cosmological distances. The emission spots appear to follow Keplerian orbits, and so with some disk modelling, the size of the orbit and hence the angular diameter distance can be deduced directly.

Gravitational waves assume general relativity. The masses of merging compact objects and luminosity can be obtained from the shape of the waveform. That is to say, there is no need for an empirical calibration of their intrinsic luminosities, and instead the observational challenge is to determine the redshift of the source. Often referred to as standard sirens rather than standard candles, a gravitational wave event whose source galaxy has been identified (by locating the optical counterpart) is referred to as a “bright siren”, otherwise it is called a “dark siren”. Most gravitational wave events are dark, but progress can be made statistically with them given sufficient numbers.

For gravitational lenses, general relativity links the time delay caused by the lensing of the background source (a combination of both the longer path and time dilation) and the mass distribution of the lensing galaxies. The absolute time delay is not known, but if a rapidly varying source like a quasar can be seen in multiple images, the relative time delay between images allows the angular diameter distance of the lens to be calculated. In this case, the challenge is to obtain enough constraints on the mass distribution of both the lensing galaxies and the general concentration of matter along the line of sight, using for example the velocity dispersions and surface brightness of the lensing galaxies, and imaging data.

2.4 What could cause the tension?

Using the word “tension”, cosmologists mean the discrepancy in measurements of \(H_0\) is at a level which is large compared to the reported errors. This means that if the values and errors are correct, this is very unlikely to be the result of chance.

Measuring the Hubble constant has always pushed the limits of the available telescopes of the day, and as a consequence observers have to be very careful to avoid bias in their derivations of \(H_0\), and have accounted for all errors. Hubble believed he had one population of Cepheids, whereas we know today he had two, and had also confused nebulae with bright stars. Alternatively, many researchers interpret the tension in the spirit of the precession of the perihelion of Mercury: something is wrong with the (Newtonian) model and a new one is needed (general relativity). We can categorise explanations as follows:

-

Observational bias. An observational bias is an error in mean photometry that would be expected to increase with magnitude or distance. To give some examples, consider first crowding. For distant stars, resolving them from their neighbours becomes harder, therefore, their photometry will be progressively more blended with other stars the more distant they are. Blending increases the apparent magnitude, and changes the colour (see for example the discussion in Sect. 4.2 in Javanmardi et al. 2021). For very faint stars, the response of the detector may be non-linear (Riess et al. 2019), and needs to be corrected. Another issue is combining observations between ground and space telescopes, as in general fainter stars will be observed from space, but nearby ones more cheaply from the ground. Aside from atmospheric extinction, each instrument has different passbands, detector response and resolution, meaning the magnitudes of the same star observed in each telescope will be different. Photometry must be transformed to a common system (see for example Eqs. 10–12 in Riess et al. 2016), and if not done (or done incorrectly) some bias will likely have been introduced. Any parameters derived from photometry—such as photometric redshifts—would inherit the same propensity to bias.

-

Astrophysical bias. An astrophysical bias occurs when the properties of the object being studied are not fully resolved, and those properties differ with distance. For example, consider Cepheids in the LMC and SN Ia hosts. The LMC is close so Cepheids with a full range of periods can be seen, whereas for distant galaxies only the brighter Cepheids with longer periods are seen. Additionally, the LMC is metal-poor compared to a typical spiral galaxy, the Cepheids there may be expected to be relatively metal-poor compared to those in SN Ia hosts. Hence, any curvature in the Leavitt law, or mis-calibrated metallicity dependency could bias distances (see for example Freedman and Madore 2010). A second example is the step-like link between SN Ia magnitudes and properties of the host galaxy (Smith et al. 2020 and references therein). This could indicate there are two distinct populations of SN Ia. If then the SN Ia in the 19 galaxies where both Cepheids and SN Ia were of mostly one type, whereas the rest a blend of both types, \(H_0\) would be biased by the calibration of SN Ia.

-

Statistical bias. The main causes of statistical bias will be selection effects and scatter as we discussed in the introduction. Statistical biases can be corrected by running random simulated observations through the same selection and analysis pipeline, but the simulations will themselves need some physical parameter choices, perhaps determined from previous surveys, or fixed in advance to “reasonable” levels. In Bayesian analysis, residual dependence on the choice of prior is a feature of sparse observations. Statistical bias correction is subtle and difficult, as we see later in the sections on parallax and SN Ia.

-

Physics of \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\). Before invoking new physics, could the explanation be found within \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\)? Cosmological formulae such as Eq. (7) are derived from a homogeneous, isotropic universe. Could corrections allowing for inhomogeneities be large enough to explain the tension? A specific example is the “Hubble Bubble” or local void proposal (for a recent example, see Shanks et al. 2019), in which we are by chance located in an under-dense region, and our local \(H_0\) is different from the “universal” one. Additionally, inhomogeneities mean we must correct redshifts for peculiar velocities, and further the propagation of light through overdense or underdense regions might bias our analysis (Kaiser and Peacock 2016).

-

New Physics. If the expansion history of the universe were different to \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\), \(H_0\) inferred from the CMB or BAO might be brought into alignment with the local value. Alternatively, performing our analysis of a non-\({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\) universe using \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\) formulae may have confused us. For example, an extra particle species would increase the pre-recombination expansion speed, so reduce the size of the sound horizon: sound waves have less time to propagate before they are frozen in. To keep the same observed angular size of the CMB temperature fluctuations, the value of \(H_0\) calculated from the CMB will increase (see Eqs. 11, 13, 14). However, as we see later \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\) makes many other successful predictions, such as the CMB spectrum itself or primordial element abundances, and is not lightly tampered with.

2.5 Is the tension significant?

The tension is often quoted as the number of standard deviations “\(m\sigma \)”. In particle physics, the meaning is clear: there are millions of collisions and probability is frequentist. There is no need to work in a Bayesian framework, with some prior assumption of a parameter to update with new data. The law of large numbers drives distributions to Gaussian normal shape, and we can translate \(m\sigma \) to a probability of occurrence by chance. At the \(5\sigma \) level, it is unanimously agreed new physics has been detected. None of the above applies in cosmology!

Nevertheless, that the tension is significant should not be in doubt: see Fig. 2. But we are looking for more from our data analysis, and there are three ways in which Bayesian statistics are helpful, which we now briefly survey.

Bayes’ theorem states that the posterior probability distribution is

where D is the data and \(\theta \) are the parameters of the model \({\mathcal {M}}\) of interest. For example \({\mathcal {M}}\) might represent \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\) with its associated parameters including \(H_0\) and \({\mathcal {M}}_{1}\) some extension of it with additional parameters. \(P(\theta \mid {\mathcal {M}})\) is any prior belief in the parameters of the model and \(P (D \mid \theta , {\mathcal {M}})\) is called the likelihood, typically specified by the team analysing the data. The denominator

is called the evidence. An extended cosmological model will have a smaller evidence if there exist large values of the parameter space with low likelihood, even if it agrees better with the data. Bayesian evidence then naturally embodies Ockham’s razor: a simpler model will have a larger evidence, unless the extended model has a significantly better fit to the data.

Second, Bayesian statistics can also help in re-analysis, in the hope that the data itself may reveal issues. A Bayesian hierarchical analysis was used by Feeney et al. (2018) to test relaxing distributional and outlier assumptions embedded in the \(\chi ^2\) fit used in SH0ES analyses. Cardona et al. (2017) have re-analysed SH0ES data using “hyperparameters”, which are weightings of datasets proposed as a measure of credibility by Lahav et al. (2000). An agnostic prior for the weights is set, and the hyperparameters are marginalised over. Both results are consistent with SH0ES. Bernal and Peacock (2018) extend the hyperparameter method by adding a free parameter shift in the mean of each dataset to account for unknown systematics, which they dub “BACCUS”. Using this to combine Planck, SH0ES and other datasets, produces a compromise. As shown in Fig. 4, the posterior middles the two with much larger error bars, which perhaps is unsurprising given the agnosticism of the method. Such types of analysis need to be taken with a grain of salt: data that is in tension should not be combined, and BACCUS is not a substitute for a critical analysis of why the tension has happened. However, if one demands a method to merge disparate results in a Bayesian framework, BACCUS is a way to achieve that.

An illustration of BACCUS applied to Planck, H0LiCOW and SH0ES data, whose posteriors are shown as thin grey lines. Conventional (orange) is the standard Bayesian combination assuming equal weighting, w/Rescaling (blue) is equivalent to hyper-parameters, w/Shifts (brown) adds an unknown systemic error offset to each dataset, and w/Shifts + Rescaling (green) combines hyper-parameters and systemic offsets. Image reproduced with permission from Bernal and Peacock (2018), copyright by IOP/SISSA

Third, we may want to know how valid a combination of data sets is. If two posteriors for the same parameter barely overlap, a Bayesian analysis will seriously mislead with error bars that are too small, as shown by the yellow line in Fig. 4. We seek a statistic that is symmetric, (reasonably) independent of prior assumptions and models, and straightforward to calculate and interpret. The R statistic

compares the evidence of dataset \(D_A\) in light of knowing \(D_B\) to that of \(D_A\) alone, but is dependent on the prior and so is not usually comparable between different papers. Handley and Lemos (2019) define a new statistic called “suspiciousness” as

where I is the information ratio \(\log I = {\mathcal {D}}_{A} +{\mathcal {D}}_{B} - {\mathcal {D}}_{AB}\) which quantifies the information gain between prior and posterior. \({\mathcal {D}}_A\) is defined as

and \({\mathcal {D}}_B\) and \({\mathcal {D}}_{AB}\) are defined similarly by replacing \(A \rightarrow B, AB\), respectively. This is independent of the prior and (being an integral) the choice of parameters. We can interpret \(\log S \ll 0\) as the two data sets being in tension: loosely speaking, the evidence of combining them does not exceed the information of considering them separately. Therefore, suspiciousness fits the criteria of simplicity and interpretation we outlined above.

Finally, even in light of the tension, we cannot dodge the question posed in our introduction: “All this debate is interesting, but which value for \(H_0\) should I use, and is it valid to use that in \({\varLambda} {\text{CDM}}\)?”. We suspend judgement until after we have surveyed the data and potential new models.

3 Measuring \(H_0\)

3.1 Parallax

Parallax is both the oldest astrometric technique, and the easiest to understand. Hold out your thumb at arm’s length, relative to some fixed point on the wall, and alternately close one eye and then the other. Relative to the fixed wall, the apparent position of your thumb will change, and this is how our depth perception works: the smaller the change in position, the longer your arm must be. The same principle works with stellar distance, where now our “binoculars” correspond to the Earth’s position on opposite sides of its orbit. The change in a fixed star’s position \(2\varpi = \theta _1 - \theta _2\) arcseconds, due to the change in the Earth’s position by 2 a.u. over 6 months leads to the distance \(d = 1/\varpi \) parsecs.Footnote 5 Our measurement of position must be very precise. Although the nearest star, Proxima Centauri, has a parallex of approximately 0.77 arcseconds, modern measurements target a remarkable 10 \(\,\mu \)as, which is the size of a thumbnail on the Moon as seen from Earth.

Modern parallax measurements began with the satellite Hipparcos (the name alludes to the ancient Greek astronomer Hipparchus, who measured the distance to the Moon). Launched by the European Space Agency in 1989, it measured the parallaxes of 100,000 stars at an accuracy of up 0.5 milliarcsecond (mas), the fixed background frame now being extragalactic sources such as quasars. Although undoubtedly impressive, at 1000 light years an error of 0.5 mas would still be a distance error of 15%. A further drawback is Cepheids, an important part of the distance ladder we discuss shortly, are relatively rare stars and only a handful are located in our neighbourhood of the Milky Way.

Moving on to the present day, our two best current sources of parallax are Gaia and the Fine Guidance Sensor/Wide Field Cameras (FGS/WFC3) aboard the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). Gaia was launched in 2013 and the mission goal is to measure over a billion stars (including 9,000 Cepheids and half a million reference quasars), both in our galaxy and satellites like the LMC. The mission-expectation precision is 7\(\,\mu \)as at \(m=12\), rising to 26\(\,\mu \)as at \(m=20\) (Gilmore 2018). Gaia does this by slowly scanning the sky with two telescopes set at relative angles of \({106.5}^{\circ }\), to make a one-dimensional measurement of the time and position of each star that slowly drifts across the CCD. Up to 70 measurements will be made for each star, which allows the additional calculation of proper motions, and even small changes in position caused by the gravitational tug of planets orbiting the star. The HST operates on similar principles in “spatial scanning” mode; although it cannot survey like Gaia, when focused on nearby Cepheids its errors appear competitive (Riess et al. 2018a).

Gaia’s high precision is dependent on a very stable mechanical structure of the spacecraft. A variation in the angle between the two fields (which might be caused by thermal expansion) could cause spatial variations in apparent parallax, or if synchronous with the scan period even a fixed systematic offset. Indeed, such a variation has been inferred from the interim Data Release 2 (DR2) (Gaia Collaboration 2018). The average of the quasar parallaxes in it is \(-29\,\mu \) as (negative parallaxes can happen when position measurement error is larger than the parallax), and there were indications this “zero point” may vary with stellar colour, luminosity and position on the sky (Arenou et al. 2018). Riess et al. (2018b) compared HST Cepheid parallaxes to Gaia, simultaneously solving for the Gaia zero point and Cepheid calibration. They found a difference between them \(46\pm 15 \,\mu \) as, with Gaia parallaxes again appearing too low. As the typical parallax of a Milky Way Cepheid is \(400\,\mu \) as, this is very material to distance estimates. Breuval et al. (2020) creatively replaced DR2 Cepheid parallaxes with those of resolved bound binary companions (where available), which being dimmer are closer to the ideal magnitude range for Gaia.

During the preparation of this review, Gaia Early Data Release 3 was made available, and has already by used by Riess et al. (2021) to revisit Gaia parallaxes. Gaia EDR3 is not intended to be the final word, but indeed Cepheid zero points seem now to be reduced below \(10\,\mu \) as. A calibration of Cepheids using 75 Gaia parallaxes only gives \(H_0 = 73.0 \pm 1.4 \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\), which is slightly lower, but consistent with their previous result based on HST parallaxes.

Before moving on to discuss alternative calibrations, we will first digress into a discussion of parallax bias. The potential for bias occurs in any astrophysical observation, and is often the subject of lengthy analysis in \(H_0\) papers. As it is most easily understood in the context of parallax, it is helpful to discuss it here.

Parallax bias is usually referred to as Lutz–Kelker–Hanson (LKH) bias (Lutz and Kelker 1973; Hanson 1979). This is a summation of three quite different effects: non-linearity of the desired variable (distance) with respect to the observed variable (parallax), population bias (have we observed the object we intended to, or did we confuse it with something else?), and selection bias (our surveys are normally magnitude limited, so we will only “select” objects for which \(m<m_0\)).

To explain non-linear bias, imagine we have a symmetric error in our parallax measurement, such as might be caused by an instrumental point spread function. To be concrete, suppose the likelihood of measuring \(150\,\mu \) as is the same as measuring \(50\,\mu \) as when \(100\,\mu \) as is the true value. If we average the distance, we will obtain \({\bar{d}} = 6666.67 + 20000 = 13,333\) which is biased with respect to the true distance of 10,000 parsecs. In mathematical terms, because \(d = 1/\varpi \), then \({\mathbb {E}}[d] \ne 1/{\mathbb {E}}[\varpi ]\).

Population bias arises in parallax when we consider a broad survey of stars at a given distance r from our position. Assuming a roughly constant spatial density of similar stars, there are more stars in the shell \((r, r+\varDelta r)\) than there are in the shell \((r - \varDelta r, r)\) for some finite \(\varDelta r\). Hence, there are more (further) stars whose parallaxes may be over-estimated to place them at r than (closer) stars whose parallaxes may be over-estimated. Taken to extremes, there are huge numbers of stars with effective parallaxes of zero, waiting for their small but finite chance to “crowd in” to a given measured parallax. This will bias observed parallaxes too low. Note that if we were certain of our identification of the star (as we would be for a Milky Way Cepheid close to us), we need not consider population bias: it would stand out from the crowd (Fig. 5).

An illustration of Lutz–Kelker–Hanson population bias. Assume each parallax measurement can be in error by up to \(\pm \delta \varpi \). In the figure on the left, there is a constant spatial density of stars. Then, the region \((\varpi , \varpi -\delta \varpi )\) has a greater number of stars that can scatter to the observed parallax \(\varpi \) than the region \((\varpi , \varpi +\delta \varpi )\) and parallaxes are biased too low. Conversely in the figure on the right, the stellar density drops sharply beyond \(\varpi \) due to either the edge of the population or magnitude limitations. More stars are available to scatter out than in, and parallaxes are biased too high

Conversely, suppose we were observing close to our magnitude limitations. Now the opposite bias would occur: we cannot see the further stars, so they cannot crowd in. But the same number of closer stars are available to crowd out, so our observed parallaxes will now be biased too high. This is the well-known Malmquist bias (Malmquist 1922), and is a major issue for surveys as naturally we will try to see as far as we can!

To deal with bias then involves modelling of the instrumental error, the selection function, the population scatter and so forth. In modern surveys, this is normally done by constructing simulated catalogs with known physical parameters and some assumptions, and putting those catalogs through the same analysis pipeline as the real data to see what biases emerge. For example, Riess et al. (2018a) compute distance modulus biases of between 0.03 and 0.12 mag for MW Cepheids using a model for galactic stellar distributions. If working in a Bayesian framework, a posterior distribution for the distance may be derived using the method of Schönrich et al. (2019). An alternative is to work directly with the parallaxes, instead converting Cepheid magnitudes to predicted parallaxes as done by Riess et al. (2018b). As the magnitudes are measured considerably more accurately than the parallaxes, bias corrections to the magnitude to parallax conversion are not necessary. To check the predictions of LKH bias, Oudmaijer et al. (1998) compared ground-based to Hipparcos parallaxes, finding a bias towards brighter magnitudes up to relative error \(\approx 30\%\), and dimmer magnitudes for larger error when Malmquist bias is dominant, as one would expect from the discussion above.

We end our digression on biases here and move on to discuss other geometrical distances.

3.2 Detached eclipsing binaries

Imagine we had a star for which we knew the surface radiant flux density J, and the physical size R. The stellar luminosity would straightforwardly follow as \(L = 4\pi R^2 J\), and we would have a standard candle.

Cool, stable, helium-burning giants (that is, red clump) are sufficiently bright to be seen outside the Milky Way. For these “late-type” stars, just such an empirical relationship can be established for the surface brightness \(S_V\) defined as

where \(\phi \) is the stellar angular diameter, and V the visual band magnitude. This relationship has been calibrated by angular diameters obtained from optical interferometry of nearby stars, and is given by

where \(V-K\) is the colour difference between magnitudes in the V and \(2.2 \;\,\mu \)m near-infrared K band (Pietrzyński et al. 2019). The scatter is just 0.018 mag. Rearranging the definition of surface brightness and with \(\phi = 2R / d\) it then follows that

where R and \(\phi \) have been converted to solar radii and milli–arcseconds, respectively. The pre-factor is purely geometric.

But how can we know the radius of distant stars? Eclipsing binaries allow just that. If the stars are well separated enough to spectroscopically resolve each one,Footnote 6 but close enough to eclipse each other, we can obtain their individual surface brightnesses, colours, radial velocities, eclipse depths and shapes, and the orbital period. With this data, the radius (and other physical parameters such as mass, eccentricity and inclination of the orbital plane) of each star can be solved for. Such an alignment of the stars is of course rare, but sufficient numbers do exist! By painstakingly observing 20 systems in the LMC over more than 20 years (covering many eclipses) Pietrzyński et al. (2019) determine the stellar radii to 0.8% accuracy. Crowding can be easily spotted in the light curve and removed. They derive \(\,\mu _{\mathrm{{LMC Centre}}} = 18.477\pm 0.004\; \text{(stat) } \pm 0.026\; \text{(sys) }\), where the main contribution to the systemic error budget is the \(S_V\) relation above.

This is the most accurate measurement of the distance to the LMC to date. As we shall see shortly when we discuss standard candles, this result has become key to many recent \(H_0\) results: every standard candle can be found in the LMC, and the low error budget allows for a very accurate calibration.

Looking forwards, although DEBs have been found in M31 they are “early-type” stars with hot atmospheres, for which a reliable surface brightness to colour relation has not been established. The hope is future 30 m-class telescopes will have sufficient spectroscopic resolution to extend this to late-types in M31 and other local group galaxies (Beaton et al. 2019).

3.3 Masers

Maser emission occurs when thermal collisions in warm gas in an accretion disk around the central black hole of a galaxy drive a population inversion of molecular energy levels. Such systems are rare: the disk must be “just right”, not too hot, and not too cold, and have suitable local molecular abundance. The Type 2 Seyfert galaxy NGC 4258 at a distance of 7.5 Mpc is just such a system. Isolated bright spots of 22.235 GHz maser emission (from a hyperfine transition of \({\mathrm {H}}_{2}{\mathrm {O}}\)) can be seen in three regions on the sky stretching 20 mas (\(\sim 0.1\) ly) long, with the overall shape of a warped line. After subtracting the overall system redshift, the spots on one side are blue-shifted by \(\sim 1000 \,\hbox {kms}^{-1}\), the other side is red-shifted by the same amount, and the spots in the middle are low velocity (Argon et al. 2008). If the spots are observed for long enough, their accelerations and proper motion can be obtained from the steady drift of their Doppler velocities and positions. The central spots show the lowest l.o.s. velocity and highest acceleration, and the outer spots having the highest velocity and lowest l.o.s. acceleration.

The key assumption these observations support is that all the spots form an orbital system with shared parameters, as it is anticipated that disk viscosity will have reduced the orbits to close to circular. The disk shape is then modelled (including such parameters as inclination, warp, residual eccentricity and so forth), fitted and the orbital parameters of the spots derived. The outer dot velocities v show a Keplerian behaviour with radius: \(v^2 \propto GM/r\), and as the acceleration is then \({\dot{v}} \propto GM/r^2\), the physical radius of the system can be determined. The angular diameter distance is then

where \(\theta \) is the angular impact parameter. Humphreys et al. (2013) have observed NGC 4258 for 10 years at 6 monthly intervals using VLBI interferometry, which resolves the relative position of the maser spots to \(<3\;\,\mu \)as accuracy (even the tectonic drift of the ground radio telescopes must be corrected for). The Doppler shifts are measured to within an accuracy of \(1 \;\hbox {kms}^{-1}\), and the central spots accelerate by \(\sim 10\;\hbox {kms}^{-1} \mathrm {yr}^{-1}\). The proper motions \({\dot{\theta }} \;\,\mu \text{ as } \text{ yr}^{-1}\) provide additional information as \(d_A = v / {\dot{\theta }} \; \text{ Mpc }\). This pattern fits an accretion disk orbiting a \(10^7 \,M_{\odot }\) black hole.

The UGC 3789 maser system, showing the warped disk, velocities and acceleration of maser spots. The top left and top right figures show the LOS velocities in \(\hbox {kms}^{-1}\) relative to the central blackhole, offset by position in milliarcseconds; the GM/r curve shape is apparent. The top centre panel shows the LOS acceleration in \(\hbox {kms}^{-1}\) per year, calculated from the velocity drifts over 3 years of observations. In the bottom panel, we schematically show the warped disk and projected spots. UGC 3789 is at a distance of 46 Mpc so 1 mas \(\simeq 0.24\) pc. The disk and maser spot data is available in Reid et al. (2013)

Reid et al. (2019) derive the distance as \(d=7.576 \pm 0.082 \text{(stat) } \pm 0.076 \text{(sys) }\) Mpc, an accuracy of 1.4%, competitive with the LMC distance error. The main statistical contribution to the error budget is the positional error of the \(\sim 300\) spots.

Only 8 megamaser galaxies have been detected, with the furthest being NGC 6264 at 141 Mpc, and it is unlikely more will now be found at usable distances. We illustrate the data for UGC 3789 from Reid et al. (2013) in Fig. 6a, b. The Megamaser Cosmology project (Pesce et al. 2020) have used six of these galaxies to find \(H_0 = 73.9 \pm 3.0 \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\), independently of distance ladders.

Although it is too close to determine \(H_0\) directly (as its peculiar motion could be a large fraction of its redshift), NGC 4258 has become a key calibrator of the distance ladder, owing to its low error budget. Its particular usefulness is that, unlike the LMC or SMC, it is a fairly typical barred spiral galaxy, similar in morphology and environmental conditions (metallicity, star-formation rate and so forth) to the ones in which Cepheids and Type Ia supernovae are seen at greater distances. Using Cepheid and SN Ia data from Riess et al. (2016), Reid et al. (2019) find \(H_0 = 72.0 \pm 1.9 \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\) using solely NGC 4258 as the geometric calibrator.

3.4 Cepheids

Having discussed calibrators, we can now talk about the “engine room” of distance ladders. Cepheids form two classes, but it is the younger, population I, classical Cepheids which are of interest. These are yellow bright giants and supergiants with masses 4–20 \(M_{\odot }\) and their brightness cycles over a regular period, between days and months, by around 1 magnitude. They are bright, up to 100,000 \(L_{\odot }\), and they can be seen out to 30 Mpc with the HST. Although Milky Way Cepheids had been observed and catalogued since the 18th century, it was first discovered by Henrietta Swan Levitt in 1908 that there was linear relation between the logarithm of their oscillation period and absolute magnitudes, the Leavitt period-luminosity law (we use the term P-L law for Miras). She had been observing Cepheids in the SMC and LMC, using the Harvard College Observatory telescope, and decided to rank them in order of magnitude. As stars in the LMC will have roughly the same distance from the Earth, the Leavitt law was immediately clear from their apparent magnitudes. In fact, one could say modern extragalactic astrometry began with her groundbreaking discovery.

That stars can pulsate is not so surprising; after all, a star is in local equilibrium, and would be expected to oscillate about the equilibrium given any perturbation. However, something must drive the oscillation otherwise it would dissipate. For Cepheids, the driver is heat-trapping by an opaque layer of doubly-ionised He surrounding a He-burning core. The trapped heat increases pressure, which expands the star, cooling the ionised He to the point where it can recombine and, therefore, becomes transparent. As the radiation escapes, the core cools and re-contracts, which in turn releases gravitational energy into the He layer. The He heats, re-ionises and the cycle repeats, with period proportional to the energy released. The Cepheid population lies in an instability strip in the horizontal branch of the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram; the cool (red) edge of the population is thought to be due to the onset of convection in the He layer, and the hot (blue) edge by the He ionisation layer being too far into the atmosphere for pulsations to occur. They, therefore, form a well-defined population.

A straightforward understanding of the origin of the Leavitt law can be found in thermodynamic and dynamic arguments. The luminosity of a Cepheid will depend on its surface area via the Stefan–Boltzmann law \(L = 4\pi R^2 \sigma T^4 \), which expressed in bolometric magnitudes is

The stellar radius can be mapped to the period by writing an equation of motion for the He layer as

where r denotes the radial position of the layer, p is the pressure and m the mass of the layer. For adiabatic expansion, it is then straightforward to solve for the period P and we find \(P \sqrt{{\bar{\rho }}} = \text{ const. }\) where \({\bar{\rho }}\) is the mean density (for further details see Cox 1960). With \({\bar{\rho }} \propto \; R^{-3}\) and temperature mapped to colour \(B-V\), we obtain the Leavitt law as

where P is the period in days, \(\alpha \), \(\beta \) are empirically calibrated from the Cepheid data, and for the zero-point \(\gamma \) we need a distance measurement.

It is preferable to use so-called Wesenheit magnitudes, which are constructed to be reddening-free, and have a reduced colour dependence (intrinsically redder Cepheids are fainter). Let’s see how this works in practice. Riess et al. (2019) define an NIR Wesenheit magnitude \(m_H^W \equiv m_{\mathrm{F160W}} - 0.386(m_{\mathrm{F555W}} - m_{\mathrm{F814W}})\) using HST filter magnitudes, where the numerical constant is derived from a reddening law. They observed 70 LMC Cepheids with long periods, and after setting \(\beta = 0\), they derive \(\alpha = -3.26\) with intrinsic scatter 0.075 mag. By comparison, the scatter using solely optical F555W magnitudes is 0.312 mag. After subtracting the DEB distance modulus (Pietrzyński et al. 2019), we obtain \(\gamma = -2.579\). The formal error in the Cepheid sample mean is 0.0092 mag, equivalent to 0.42% in distance (Fig. 7).

Illustration the Leavitt law in four galaxies used for the local distance ladder. The LMC and N4258 are the two main calibrators of Cepheid distances. For the two example SN Ia hosts N4536 and N1015, it is harder to observe the fainter, shorter-period Cepheids. The slope is fixed at \(-3.26\), corresponding to the best estimate global fit in Riess et al. (2016), and magnitudes are \(m_H^W\). We have inverted the normal decreasing magnitude axis used in the literature for presentation purposes

We would now like to feel that we can deduce the distance to any galaxy we can find Cepheids in, by applying this law to convert periods to absolute magnitudes, and comparing to the apparent magnitudes we observe. As is usual, though, things are not that simple! There are three principle objections:

-

Are Cepheids in the LMC the same as the ones in distant galaxies? The LMC has a lower metallicity than a typical spiral galaxy, so can we expect the Cepheids found there to have the same brightness? Unfortunately, it is hard to determine the metallicity of a Cepheid from its colour alone, and studies on the effects of metallicity are variable (Ripepi et al. 2020). One might try extending the Leavitt law to add a metallicity term \(\kappa \) [Fe/H]. Riess et al. (2019) have estimated Cepheid metallicity in the LMC based on optical spectra of nearby HII regions, and find \(\kappa = -0.17 \pm 0.06\), which is consistent with an earlier estimate from Freedman and Madore (2010) that LMC Cepheids are 0.05 mag dimmer than galactic Cepheids, and later results (Gieren et al. 2018; Breuval et al. 2021).

-

Is the Leavitt law linear? This matters for \(H_0\), because the Cepheids seen in distant galaxies have longer periods than those used to calibrate the Leavitt law: they are brighter and more easily observed at distance. So, \(\log {P} \sim 1.5\) for Cepheids in SN Ia host galaxies, whereas the average for the LMC is \(\log {P} \sim 0.8\). If the Leavitt law is curved, a bias would be introduced. This can be dealt with by either introducing a separate calibration for short and long period Cepheids, or selecting only long period nearby Cepheids for calibration.

-

Can we obtain clean astrometry of very distant Cepheids? We want to observe Cepheids as far away as we can, to maximise the overlap with the SN Ia observations. But pushing the limits of resolution brings the risk of crowding, whereby the Cepheid photometry is blended with nearby dimmer, redder and cooler stars. Indeed, this seems to be the main cause of the increased scatter in residuals for distant galaxies. There are some ways to deal with crowding: Riess et al. (2016) (hereafter R16) add random Cepheids to images of the same galaxy and put them through the same analysis pipeline, to see how well input parameters are recovered. Figure 8 shows an example of this. Cepheids which are outliers in colour, indicative of high blending, may be discarded (removing the colour cut lowers \(H_0\) by \(1.1 \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\)). Another way to test for a crowding bias is to look for compression of the relative flux difference from peak to trough (a more blended Cepheid will be more compressed) as is done in Riess et al. (2020). Using an optical Wesenheit magnitude, in which stars may be less crowded than the NIR one, reduces \(H_0\) by \(1.7 \,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\) (R16), although the argument can be made this is due to higher metallicity effects in the optical (Riess et al. 2019). As with metallicity, the matter of crowding continues to debated.

Illustration of Cepheid photometry from SN Ia host galaxies from Riess et al (Riess et al. 2016). U9391 is the most distant with a distance modulus of \(32.92 \pm 0.06\). The association of Cepheids with spiral arms is clearly visible, and in the bottom left is an example crowding correction for point sources and background flux. The scatter around the Leavitt law is \(\sim 0.7\) mag, thought to be due to residual crowding effects

Systematic error analysis is provided in Sect. 4 and Table 8 of R16, where the effect of some different analytical choices such as breaks in the Leavitt law, different assumed values for the deceleration parameter \(q_0\), and methods of outlier rejection are shown to be \(\pm 0.7\%\). This may not cover all potential systematics. In a recent talk, Efstathiou (2020) re-examined the Leavitt laws of galaxies presented in R16. Calibrating each galaxy individually, the slopes of SN Ia host galaxies are generally shallower than M31 or the LMC, which should not be the case if Cepheids are a single population. A change in the slope will alter the zero-point, as would a change in the distance calibration. It is then noted that forcing the slope of the Leavitt law to \(-3.3\) (the M31 value), in combination with using only NGC4258 as the anchor, lowers the R16 \(H_0\) value to \(70.3 \pm 1.8 \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\) (Equation 4.2b). Additionally, there appears to be tension between the relative magnitudes of Cepheids in the LMC and NGC4258, and the distance modulus implied by Masers and DEBs; calibrating with solely the LMC gives a higher \(H_0\) value by \(4.4 \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\). It is a feature of \(\chi ^2\) fits (as used in R16) that the joint solution will be drawn to the data with the lowest error, which in this case is the LMC value. But if two subsets of the data are in tension, it is uncertain that the one with the lowest \(\chi ^2\) would have the least systematics.

Such analyses do not show one value is preferable over another, nor can they show where any discrepancy may lie—it might be metallicity effects, crowded Cepheid photometry, the NGC4258 distance, or some other systematic. Re-analyses of the results of R16 by various authors (Feeney et al. 2018; Cardona et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2017; Follin and Knox 2018; Dhawan et al. 2018) use the same Cepheid photometric reduction data so are not independent as such.

Research has accelerated to close down these potential issues. We have already mentioned replacing LMC and NGC4258 Cepheids with Milky Way Cepheids in the section on parallax. In a recent paper, Riess et al. (2020) show crowding effects can be detected as a light curve amplitude compression, and that their correction method has been robust. Finally, Javanmardi et al. (2021) fully re-derive the Cepheid periods and luminosities from the original HST imaging for NGC 5584 (which is face-on to the line of sight), intentionally using different analytical choices, finding no systematic difference in the light curve parameters.

All this said, it would be clearly preferable if we had some other candles to check against Cepheids. We now turn to two possibilities, Miras and the Tip of the Red Giant Branch.

3.5 Miras

Miras are variable stars that have reached the tip of the Asymptotic Giant Branch (AGB), comprising an inert C-O core, and a He-burning shell inside a H-burning shell. Their mass is 0.8–8 \(M_{\odot }\), although they are typically at the lower end of this range. Their large size of \(\sim 1\) a.u. means they are actually brighter by 2–3 mag than Cepheids in the NIR. That they follow a P-L law was first established in 1928 (Gerasimovic 1928), but being tricky to categorise and observe, were not extensively studied until the demand for cross-checks on Cepheids has brought renewed interest in them.

Miras form two distinct populations with O-rich and C-rich spectra, with the O-rich ones exhibiting somewhat less scatter than the C-rich (Feast 2004), but more than Cepheids. Miras have very long periods \(90<P<3000\) days and their light curves have many peaks of variable amplitude superimposed (see for example Fig. 3 in Yuan et al. 2017), so investment in observation time is needed to reliably determine P. The P-L law curves upwards at around \(P \sim 400\) days, where it seems likely the extra luminosity has been due to episodes of Hot-Bottom-Burning, so an extra quadratic term is required. Miras have high mass loss rates, and the surrounding dust cloud means Wesenheit magnitudes will be less reliable at subtracting reddening compared to Cepheids (because a standard reddening law is assumed in constructing them). Lastly, a size of 1 a.u. would mean their angular diameter is comparable to their parallax, and in addition the photocentre moves around the star, making parallax measurements challenging.

So why bother with them? Their advantages versus Cepheids is that they are (a) more numerous, and, therefore, easier to find in halos where there is less crowding (b) older, so can be found in all types of galaxies including SN Ia hosts with no Cepheids (c) \(2-3\) magnitudes brighter than Cepheids in the near infrared. Given imaginative observation strategies and careful population analysis, the issues above can be addressed, and modern studies now exist for Miras in the LMC (Yuan et al. 2017), NGC 4258 (Huang et al. 2018), and the SN Ia host NGC 1559 (Huang et al. 2020).

In the first of the above, Yuan et al. (2017) establish a P-L curve using 600 Miras in the LMC. They have sparse JHK-band observations from the LMC Near Infrared Synoptic Survey (LMCNISS, Macri et al. 2015), which on their own would not be enough to establish the period, but using much denser Optical Gravitational Lens Experiment (OGLE) I-band observations (Szymański et al. 2011), they are able to establish a regression rule for the relationship between passbands, and use OGLE to “fill in” the light curves. The classification of Miras into O-rich or C-rich is also obtained from OGLE. The reference magnitude is defined as the median of maxima and minima of the fitted light curves. The period is obtained by fitting to a sum of sine functions, progressively adding harmonics if supported by a Bayesian Information Criterion.Footnote 7 They fit a lawFootnote 8

The K-band for O-rich Miras shows the lowest scatter of 0.12 mag, with \(a_0 =-6.90 \pm 0.01\), \(a_1 = -3.77 \pm 0.08\), \(a_2 = -2.23 \pm 0.2\). The zero-point is obtained using the DEB distance to the LMC given by Pietrzyński et al. (2013). By comparison, the \(m_H^W\) scatter for LMC Cepheids obtained by SH0ES was 0.075 mag (Riess et al. 2019) (Fig. 9).

A PL calibration for Miras in the LMC. While non-linearity can straightforwardly be fitted, contamination must be kept under control. As seen in the bottom three panels, Wesenheit magnitudes have more scatter compared to standard magnitudes (the opposite of applying them to Cepheids), and they also hinder separating O-rich from C-rich stars. Image reproduced with permission from Yuan et al. (2017), copyright by AAS

Huang et al. (2018) observed NGC4258 with the HST WFC in 12 epochs over 10 months. Mira candidates were identified by their V and I amplitude variation, and it was possible to use LMC data to show that using this method contamination between O-rich and C-rich could be kept to a minimum. Their “Gold” sample size was 161 Miras, and fitting Eq. (34) for apparent magnitudes gave \(a_0 = 23.24 \pm 0.01\) for F160W with scatter 0.12. Adjusting the ground-based photometry of LMCNISS to F160W equivalent, the authors calculate the relative distance modulus between the LMC and NGC4258 of \(\varDelta \,\mu = 10.95 \pm 0.01 \text{(stat) } \pm 0.06 \text{(sys) }\). This is consistent with the Cepheid value of \(\varDelta \,\mu = 10.92 \pm 0.02\) (Riess et al. 2016) and the Maser-DEB value of \(\varDelta \,\mu = 10.92 \pm 0.041\) (Reid et al. 2019; Pietrzyński et al. 2019). Similar methods are used by Huang et al. (2020) for observations of NGC 1559, with the addition of a low period cut to deal with potential incompleteness bias of fainter Miras. Using the LMC DEB and NGC 4258 distances as calibrators, they obtain \(H_0 = 73.3 \pm 4.0 \;\,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\). So Miras are consistent with Cepheids, but due to their larger error budgets, they are also consistent with Planck results.

3.6 Tip of the Red Giant branch

Red Giant branch stars are stars of mass \(\sim 0.5 {-} 2.0 M_{\odot }\) that are at a late stage in their evolution, having moved off the main sequence towards lower temperatures and higher luminosities. The core of the star is degenerate He, and as He ash rains down from the H-burning shell surrounding it, it contracts and heats up. Since the temperature range for He fusion ignition is rather narrow, and the degenerate matter means there is a strong link between core mass and temperature, the core in effect forms a standard candle inside the star, just prior to ignition. As soon as the helium flash ignites, the star moves over the course of 1 My or so (almost instantaneously in stellar evolution terms) to the red clump at a higher temperature and somewhat lower luminosity. Therefore, there is a well-defined edge in a colour-magnitude diagram that can be used to identify the tip of the red giant population just before the flash (TRGB). The TRGB is then not one single star, but a statistical average for a suitably large population.

The TRGB offers many advantages compared to other standard candles. Although red giants are fainter than Cepheids in the optical, in the K-band they are \(\sim 1.6\) magnitudes brighter. Stars at or near the TRGB are relatively common, and can be observed readily in uncrowded and dust-free galactic halos. They are also abundant in the solar neighbourhood, meaning great numbers are available for calibration by parallax (by contrast, Cepheids with good parallaxes in Gaia DR3 will number in the hundreds). Sufficient numbers to resolve the tip can be seen in globular clusters such as \(\omega \) Centuari, where well-formed colour-magnitude diagrams can resolve metallicity and extinction effects, and an absolute magnitude calibration can be made either from Gaia DR3 parallaxes (Soltis et al. 2021) or DEB distances (Cerny et al. 2021).

Like Miras, they are found in all galactic types. Observation is efficient: one does not need to revisit fields to determine periods. The James Webb Space Telescope is capable of observing red giants in the near IR at distances of \(\sim 50 \,\hbox {Mpc}\), which is comparable to Cepheid distances obtainable from the HST.

It is also beneficial that the modelling of late-stage stellar evolution is quite well understood. Empirical calibrations of absolute magnitude and residual dependence on metallicity, mass and age can be checked against the results of stellar codes. For example, the dependency on metallicity is somewhat complex: the presence of metals dims optical passbands by absorption in stellar atmospheres, and brightens the NIR. Serenelli et al. (2017) express the TRGB as a curve with linear and quadratic terms in colour. The authors find an I-band median \(M_I^{\mathrm{TRGB}} = -4.07\) with a variation with colour of \(\pm 0.08\), and a downward slope in the colour-magnitude diagram as metallicity increases. This median value is consistent with empirical calibrations.

Fitting the TRGB is equivalent to finding the mode of the gradient of the (noisy) stellar distribution in the colour-magnitude diagram, and techniques are borrowed from image processing to do this. The tip has a background of AGB stars, and the edge is sensitive to the distribution of them close to it. If the contamination is large or variable, there is a risk the mode can shift. It is, therefore, important to have a dense population of stars, and enough fields to test the robustness of the fitting process. For example, Hoyt et al. (2021) bin data by separation from the galactic centre and fit the tip separately for each bin.

The Carnegie-Chicago Hubble program (CCHP) have determined TRGB distances for 10 SN Ia host galaxies that also have Cepheid distances, using HST I-band imaging (Freedman et al. 2019). They calibrate the zero point from the TRGB of the LMC and SMC using the DEB distance, finding \(M_I = -4.049 \pm 0.022 \;\text{(stat) } \pm 0.039 \;\text{(sys) }\), which is consistent with the theoretical value above (Fig. 10).

Fitting the TRGB edge from the colour-magnitude diagram of Freedman et al. (2019). The middle panel shows the horizontally-summed (between the blue lines) and smoothed number count, from which the edge is determined by the maximum (vertical) gradient, which is the peak in the right-hand panel. The background AGB population is visible in the stars above the tip

We show in Fig. 11 their comparison of TRGB and Cepheid distances, covering a range of distances from 7 Mpc to almost 20 Mpc. By expanding their sample to non-SN Ia host galaxies, the authors show the TRGB has a lower scatter versus their Hubble diagram than do Cepheids, by a factor of 1.4. Calibrating the Pantheon SN Ia sample on TRGB distances alone gives \(H_0 = 70.4 \pm 1.4 \,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\), with the difference to SH0ES results due to the TRGB distances to the SN Ia host galaxies being further than Cepheid distances.

Comparison of TRGB and Cepheid distance moduli, from which it can be seen TRGB distances are consistently larger across a range of galaxies. The red dots are SN Ia host galaxies, the grey dots other galaxies, and the blue star is the LMC TRGB calibrator. Image reproduced with permission from Freedman et al. (2019), copyright by AAS

Currently, this result remains the subject of debate. Yuan et al. (2019) find \(M_{I} = -3.99\), which gives \(H_0 = 72.4 \pm 2.0 \,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\). They attribute their result to a different methodology to determine the LMC extinction. Freedman et al. 2019 determine the extinction applicable to the TRGB by comparison of LMC and SMC photometry in VIJHK bands, and using the lower SMC extinction as a reference point. Yuan et al. 2019 adopt the standard reddening law of Fitzpatrick 1999). They also revise the blending corrections of the older, lower resolution photometry of the SMC. Conversely, a calibration of the TRGB in the outskirts of NGC 4258 to the maser distance by Jang et al. (2021) gives a value fully consistent with Freedman et al. (2019). In a followup paper, Madore and Freedman (2020) present an upgraded methodology in which stellar photometry is itself used to separate metallicity and extinction effects (by exploiting their different sensitivities in J, H and K-band magnitudes), confirming their earlier results. Other results (Soltis et al. 2021; Reid et al. 2019; Capozzi and Raffelt 2020; Cerny et al. 2021—see for example Table 3 in Blakeslee et al. 2021) cluster evenly around these two values. We also note the difference between SN Ia zero points (Fig. 6 of Freedman et al. 2019) of the TRGB vs Cepheids appears to increase with distance, and is particularly large for one galaxy, N4308.

More recently, an updated value of \(H_0 = 69.8 \pm 0.6 \;\text{(stat) } \pm 1.6 \;\text{(sys) } \,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\) was published by Freedman (2021). New and updated values for \(M_I\) based on the anchors of the LMC, SMC, NGC 4258 and galactic globular clusters are derived. Additionally, potential zero-point systematic problems with the direct application of Gaia EDR3 data to globular clusters (as done by Soltis et al. 2021) are discussed. Each anchor is consistent with each other (although the closeness of the agreement suggests the errors may be over-estimated), and the paper brings the TRGB method on par with Cepheids in terms of number of anchors used.

The TRGB continues to attract attention because the CCHP result is very interesting: it is a late universe distance ladder that is in reduced \(2\sigma \) tension with the Planck value of \(H_0 = 67.4 \pm 0.5 \,\hbox {kms}^{-1} \,\hbox {Mpc}^{-1}\). While it cannot by itself fully resolve the Hubble tension, in combination with some other systematic—perhaps in the calibration of SN Ia (see next section)—it may offer a resolution of it that does not involve new physics.

What is also clear is that quality of a distance ladder is less a matter of quantity of objects, but rather the accuracy of calibration and control of systematics. The TRGB seems very promising, however. Once the calibration is agreed among the community, they offer the tantalising prospect of either confirming the \(H_0\) tension through two independent data sets, or reducing it to a lower statistical significance.

3.7 Type Ia supernovae

It is hard to overstate the impact of Type Ia supernovae in cosmology. At \(M \sim -19\), they are both bright enough to be seen well into the Hubble flow (the furthest to date is SN Wilson at \(z = 1.914\)), and have a standardisable luminosity. The mainstream view is that they originate from the accretion of material from a binary companion onto a carbon-oxygen white dwarf. When the white dwarf reaches the maximum mass that can be sustained by degeneracy pressure, the Chandrasekhar mass \(M_{\mathrm{ch}} = 1.4 M_{\odot }\), a runaway fusion detonation occurs destroying the white dwarf. Approximately \(\sim 0.6 M_{\odot }\) fuses into heavier elements during the first few seconds of the explosion, and the observed light curve, which peaks at \(\sim 20\) days and lasts for \(\sim 60\) days is powered by radioactive decay of \(^{56}\)Ni to \(^{56}\)Co and then to \(^{56}\)Fe. Hence, a SN Ia is a “standard bomb”, primed to explode when it reaches critical mass.

However, there is surprisingly little observational evidence to confirm the accretion theory. Both the lack of H lines and computer modelling suggest the donor star should survive the explosion, but a search of the site of the nearby SN2011fe both pre- and post- explosion have revealed no evidence of a companion. This may support an alternative “double degenerate” theory that some, or all, SN Ia originate from the merger of two white dwarves (for a review, see Maoz et al. 2014). But if that is the case, why are their luminosities so uniform? Whether SN Ia have one or two types of progenitors has important implications for the Hubble constant, which we return to shortly.

Individual SN Ia luminosities can vary by up to a factor of 2, but they are empirically standardisable by the Tripp estimator (Tripp and Branch 1999):

where \(\,\mu \) is the distance modulus, \(m_b\) ia the apparent AB magnitude, and \(M_{\mathrm{fid}}\) is the absolute magnitude of a typical SN Ia. The parameter x is the “stretch” of the light curve, which is a dimensionless measure of how long the bright peak of the light curve lasts: longer duration SN Ia are brighter. c is a measure of colour: redder SN Ia are dimmer. \(\varDelta _M\) is a correction for the environment of the SN Ia, and \(\varDelta _B\) a statistical bias correction for selection effects, analogous to the LKH bias of parallax we described earlier. \(M_{\mathrm{fid}}\) can be calibrated by finding SN Ia in galaxies for which there are Cepheid or TRGB luminosity distances, or in the inverse distance ladder approach by combination with angular diameter distances from baryon acoustic oscillations, or the CMB.

SN Ia are rare events: approximately 1 per galaxy per century, but by scanning a reasonably sized patch of sky, supernova surveys can detect hundreds per year.Footnote 9 Hence, supernovae catalogs are not uniformly distributed on the sky. However, SN Ia close enough to calibrate their magnitudes are few: there are just 19 SN Ia in galaxies with Cepheid distances from HST observations, although more are expected soon from new cycles (see for example HST proposal 16,198).