Abstract

Purpose

Determine the number of latent parallel trajectories of mental health and employment earnings over two decades among American youth entering the workforce and estimate the association between baseline sociodemographic and health factors on latent trajectory class membership.

Methods

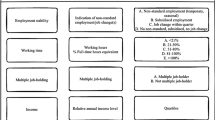

This study used data of 8173 participants from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 who were 13–17 years old in 1997. Surveys occurred annually until 2011 then biennially until 2017, when participants were 33–37 years old. The Mental Health Inventory-5 measured mental health at eight survey cycles between 2000 and 2017. Employment earnings were measured annually between 1998 and 2017. Latent parallel trajectories were estimated using latent growth modeling. Multinomial logistic regression explored the association between baseline factors and trajectory membership.

Results

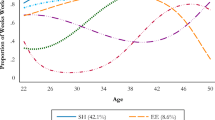

Four parallel latent classes were identified; all showed stable mental health and increasing earnings. Three percent of the sample showed a good mental health, steep increasing earnings trajectory (average 2017 earnings ~ $196,000); 23% followed a good mental health, medium increasing earnings trajectory (average 2017 earnings ~ $78,100); 50% followed a good mental health, low increasing earnings trajectory (average 2017 earnings ~ $39,500); and 24% followed a poor mental, lowest increasing earnings trajectory (average 2017 earnings ~ $32,000). Participants who were younger, women, Black or Hispanic, from lower socioeconomic households, and reported poorer health behaviors had higher odds of belonging to the poor mental health, low earnings class.

Conclusion

Findings highlight the parallel courses of mental health and labor market earnings, and the influence of gender, race/ethnicity, and adolescent circumstances on these processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability statement

The NLSY97 data is publicly available from: http://www.nlsinfo.org

References

Trogdon JG, Murphy LB, Khavjou OA et al (2015) Costs of chronic diseases at the state level: the chronic disease cost calculator. Prev Chronic Dis 12:1–9. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.150131

Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P et al (2016) Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 3:415–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30024-4

Abbafati C, Machado DB, Cislaghi B et al (2020) Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396:1204–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

Marcotte DE, Wilcox-Gök V (2001) Estimating the employment and earnings costs of mental illness: recent developments in the United States. Soc Sci Med 53:21–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00312-9

Cseh A (2008) The effects of depressive symptoms on earnings. South Econ J 75:383–409

McIntyre RS, Wilkins K, Gilmour H et al (2008) The effect of bipolar I disorder and major depressive disorder on workforce function. Chronic Dis Can 28:84–91

Dobson KG, Vigod SN, Mustard C, Smith PM (2021) Major depressive episodes and employment earning trajectories over the following decade among working-aged Canadian men and women. J Affect Disord 285:37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.019

Eaton WW, Muntaner C, Bovasso G, Smith C (2001) Socioeconomic status and depressive syndrome: the role of inter- and intra-generational mobility, government assistance, and work environment. J Health Soc Behav 42:277–294. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090215

Bockting CL, Hollon SD, Jarrett RB et al (2015) A lifetime approach to major depressive disorder: the contributions of psychological interventions in preventing relapse and recurrence. Clin Psychol Rev 41:16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.003

Burcusa SL, Iacono WG (2007) Risk for recurrence in depression. Clin Psychol Rev 27:959–985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.02.005

Keller MB (2002) The long-term clinical course of generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 63:11–16

Luo Z, Cowell AJ, Musuda YJ et al (2010) Course of major depressive disorder and labor market outcome disruption. J Mental Health Policy Econ 13:135–149

Sareen J, Afifi TO, McMillan KA, Asmundson GJG (2011) Relationship between household income and mental disorders: findings from a population-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68:419–427. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.15

Wilhelm K, Kovess V, Rios-Seidel C, Finch A (2004) Work and mental health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 39:866–873. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-004-0869-7

Hale DR, Bevilacqua L, Viner RM (2015) Adolescent health and adult education and employment: a systematic review. Pediatrics 136:128–140. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2105

Callander EJ (2016) Pathways between health, education and income in adolescence and adulthood. Arch Dis Child 101:825–831. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2015-309721

Banerjee S, Chatterji P, Lahiri K (2017) Effects of psychiatric disorders on labor market outcomes: a latent variable approach using multiple clinical indicators. Health Econ 26:184–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3286

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020) The NLSY97 sample: an introduction. https://www.nlsinfo.org/content/cohorts/nlsy97/intro-to-the-sample/nlsy97-sample-introduction-0. Accessed 1 June 2020

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020) NLSY97 Data overview. https://www.bls.gov/nls/nlsy97.htm. Accessed 15 Jul 2020

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020) National longitudinal survey of youth 1997: sample design & screening process. https://www.nlsinfo.org/content/cohorts/nlsy97/intro-to-the-sample/sample-design-screening-process. Accessed 15 Jul 2020

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020) National longitudinal survey of youth 1997: retention & reasons for non-interview. https://www.nlsinfo.org/content/cohorts/nlsy97/intro-to-the-sample/retention-reasons-non-interview. Accessed 15 Jul 2020

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020) Reasons for noninterview in the NLSY97. https://www.nlsinfo.org/content/cohorts/nlsy97/intro-to-the-sample/retention-reasons-non-interview/page/0/1/#reasons. Accessed 15 Jul 2020

Aughinbaugh A, Gardecki RM (2007) Attrition in the national longitudinal survey of youth 1997. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Washington DC

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2012) National longitudinal survey of youth 1997 health 29 youth questionnaire 97 (R13). https://www.nlsinfo.org/sites/nlsinfo.org/files/attachments/121129/nlsy97r13hea29.html#Health 29. Accessed 15 Jul 2020

Veit CT, Ware JE (1983) The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. J Consult Clin Psychol 51:730–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.5.730

Berwick DM, Murphy JM, Goldman PA et al (1991) Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Med Care 29:169–176. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B (1993) SF-36 health survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston New England Medical Centre

Holmes WC (1998) A short, psychiatric, case-finding measure for HIV seropositive outpatients performance: characteristics of the 5-item mental health subscale of the SF-20 in a male, seropositive sample. Med Care 36:237–243. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199802000-00012

Strand BH, Dalgard OS, Tambs K, Rognerud M (2003) Measuring the mental health status of the Norwegian population: a comparison of the instruments SCL-25, SCL-10, SCL-5 and MHI-5 (SF-36). Nord J Psychiatry 57:113–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480310000932

Yamazaki S, Fukuhara S, Green J (2005) Usefulness of five-item and three-item Mental Health Inventories to screen for depressive symptoms in the general population of Japan. Health Qual Life Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-3-48

Wilkinson LL, Glover SH, Probst JC et al (2015) Psychological distress and health insurance coverage among formerly incarcerated young adults in the United States. AIMS Public Health 2:227–246. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2015.3.227

Rumpf HJ, Meyer C, Hapke U, John U (2001) Screening for mental health: validity of the MHI-5 using DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders as gold standard. Psychiatry Res 105:243–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00329-8

US Inflation Calculator (2020) Consumer price index data from 1913 to 2020. https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/consumer-price-index-and-annual-percent-changes-from-1913-to-2008/. Accessed 1 Aug 2020

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O et al (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62:593–602. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

Benach J, Friel S, Houweling T et al (2010) A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. World Health Organization, Geneva

Patel V, Burns JK, Dhingra M et al (2018) Income inequality and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association and a scoping review of mechanisms. World Psychiatry 17:76–89

Nagin DS, Odgers CL (2010) Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 6:109–138. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413

Nagin DS, Jones BL, Lima Passos V, Tremblay RE (2016) Group-based multi-trajectory modeling. Stat Methods Med Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280216673085

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (2010) Mplus user’s guide, 7th edn. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Yuan KH, Bentler PM (2000) Three likelihood-based methods for mean and covariance structure analysis with nonnormal missing data. Sociol Methodol. https://doi.org/10.1111/0081-1750.00078

Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO (2007) Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Modeling 14:535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396

Berglund P, Heeringa SG (2014) Chapter 2: Introduction to multiple imputation theory and methods. In: Multiple Imputation of Missing Data Using SAS. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC

Roxburgh S (2009) Untangling inequalities: gender, race, and socioeconomic differences in depression. Sociol Forum 24:357–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1573-7861.2009.01103.x

McCabe CJ, Thomas KJ, Brazier JE, Coleman P (1996) Measuring the mental health status of a population: a comparison of the GHQ-12 and the SF-36 (MHI-5). Br J Psychiatry 169:517–521. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.169.4.516

Lund C, Cois A (2018) Simultaneous social causation and social drift: longitudinal analysis of depression and poverty in South Africa. J Affect Disord 229:396–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.050

Saraceno B, Levav I, Kohn R (2005) The public mental health significance of research on socio-economic factors in schizophrenia and major depression. World Psychiatry 4:181–185

Babcock ED (2014) Using brain science to design new pathways out of poverty. Crittenton Women’s Union, Boston

Kutcher S, Bagnell A, Wei Y (2015) Mental health literacy in secondary schools. a Canadian approach. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 24:233–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2014.11.007

Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ (2002) Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59:225–231. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.225

Salmela-Aro K, Aunola K, Nurmi J (2008) Trajectories of depressive symptoms during emerging adulthood: antecedents and consequences. Eur Jo Develop Psychol 5:439–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620600867014

Nilsen W, Skipstein A, Demerouti E (2016) Adverse trajectories of mental health problems predict subsequent burnout and work-family conflict—a longitudinal study of employed women with children followed over 18 years. BMC Psychiatry 16:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1110-4

Ferro MA, Gorter JW, Boyle MH (2015) Trajectories of depressive symptoms in Canadian emerging adults. Am J Public Health 105:2322–2327. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302817

Minh A, Sc M, Bültmann U et al (2021) Childhood socioeconomic status and depressive symptom trajectories in the transition to adulthood in the United States and Canada. J Adolesc Health 68:161–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.033

National Centre for Education Statistics (2019) Table 502.30. Median annual earnings of full-time year-round workers 25 to 34 years old and full-time year-round workers as a percentage of the labor force, by sex, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment: Selected years, 1995 through 2018. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_502.30.asp. Accessed 5 Feb 2020

Fontenot K, Semega J, Kollar M (2018) Income and poverty in the United States: 2017. Washington, DC

Frech A, Damaske S (2019) Men’s income trajectories and physical and mental health at midlife. Am J Sociol 124:1372–1412. https://doi.org/10.1086/702775

Elovanio M, Hakulinen C, Pulkki-Råback L et al (2020) General health questionnaire (GHQ-12), beck depression inventory (BDI-6), and mental health index (MHI-5): psychometric and predictive properties in a Finnish population-based sample. Psychiatry Res 289:112973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112973

Howe GW, Hornberger AP, Weihs K, Moreno F (2012) Higher-order structure in the trajectories of depression and anxiety following sudden involuntary unemployment. J Abnorm Psychol 121:325–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026243

Frech A, Damaske S (2012) The relationships between mothers’ work pathways and physical and mental health. J Health Social 534:396–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146512453929

Yu J (2019) Attention on adolescent mental disorders: the long-term effects on labor market outcomes. Int J Appl Econ 15:55–68

Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T et al (2015) The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry 76:155–162. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14m09298

Patten SB, Williams JVA, Lavorato DH et al (2015) Descriptive epidemiology of major depressive disorder in Canada in 2012. Can J Psychiat 60:23–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371506000106

Watterson RA, Williams JVA, Lavorato DH, Patten SB (2017) Descriptive epidemiology of generalized anxiety disorder in Canada. Can J Psychiat 62:24–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743716645304

Deary IJ, Batty GD (2007) Cognitive epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health 61:378–384. https://doi.org/10.1136/JECH.2005.039206

Dobson KG, Ferro MA, Boyle MH et al (2017) Socioeconomic attainment of extremely low birth weight survivors: the role of early cognition. Pediatrics 139:e20162545

Koenen KC, Moffitt TE, Roberts AL et al (2009) Childhood IQ and adult mental disorders: a test of the cognitive reserve hypothesis. Am J Psychiatry 166:50–57. https://doi.org/10.1176/APPI.AJP.2008.08030343/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/T912T2.JPEG

Dobson KG, Schmidt LA, Saigal S et al (2016) Childhood cognition and lifetime risk of major depressive disorder in extremely low birth weight and normal birth weight adults. J Dev Orig Health Dis 7:574–580

Jarman L, Martin A, Venn A et al (2014) Prevalence and correlates of psychological distress in a large and diverse public sector workforce: baseline results from partnering Healthy@Work. BMC Public Health 14:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-125

Green KM, Doherty EE, Ensminger ME (2017) Long-term consequences of adolescent cannabis use: examining intermediary processes. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 43:567–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2016.1258706

Wiens K, Williams JVA, Lavorato DH et al (2017) Is the prevalence of major depression increasing in the Canadian adolescent population? Assessing trends from 2000 to 2014. J Affect Disord 210:22–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.018

Williams DR (2018) Stress and the mental health of populations of color: advancing our understanding of race-related stressors. J health Soc Behav 59:466–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146518814251.Stress

Miranda J, McGuire TG, Williams DR, Wang P (2008) Mental health in the context of health disparities. Am J Psychiatry 165:1102–1108. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030333

Vilsaint CL, NeMoyer A, Fillbrunn M et al (2019) Racial/ethnic differences in 12-month prevalence and persistence of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders: variation by nativity and socioeconomic status. Compr Psychiatry 89:52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.12.008

Priest N, Doery K, Truong M et al (2013) A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and adolescents. Soc Sci Med 95:115–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.031

American Psychological Association (2016) Stress in America: the impact of discrimination. Stress in AmericaTM Survey. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2009/stress-exec-summary.pdf. Accessed 1 March 2021

Kwate NOA, Meyer IH (2011) On sticks and stones and broken bones. Du Bois Rev 8:191–198. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1742058x11000014

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes for Health Research Doctoral Scholarship and S. Leonard Syme Training Fellowship awarded to Dr. Dobson during her doctoral training.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KD conceptualized the research question and initial design of the study, which was then contributed to by SV, CM, and PS. The analysis was completed by KD. The initial manuscript draft was written by KD, which was then contributed to by SV, CM, and PS. All authors provided approval for the final manuscript draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Dobson, K.G., Vigod, S.N., Mustard, C. et al. Parallel latent trajectories of mental health and personal earnings among 16- to 20 year-old US labor force participants: a 20-year longitudinal study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 58, 805–821 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02398-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02398-5